University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy in Statu Nascendi

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2014 Number 32 Living a Philosophy of Early Childhood Education: A Festschrift for Harriet Article 6 Cuffaro October 2014 Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi Jeroen Staring Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Staring, J. (2014). Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi. Occasional Paper Series, 2014 (32). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2014/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi By Jeroen Staring This article explores two themes in the life of Caroline Pratt, founder of the Play School, later the City and Country School. These themes, central to Harriet Cuffaro’s values as a teacher and scholar, are Pratt’s early progressive pedagogy, developed during experimental shopwork between 1901 and 1908; and her theories on play and toys, developed while observing children play with her Do-With Toys and Unit Blocks between 1908 and 1914. Focusing on her early and previously unexplored writings, this article illustrates how Caroline Pratt developed a coherent theory of innovative progressive pedagogy. Figure 1 (left). Original drawing of Do-With doll, by Caroline Pratt. Figure 2 (right): Two wooden, jointed Do-With dolls. (Photo: Jeroen Staring, 2011; Courtesy City and Country School, New York City) 46 | Occasional Paper Series 32 bankstreet.edu/ops Caroline Pratt’s Education In 1884, Caroline Louise Pratt, age 17, had her first teaching experience at the summer session of a school near her hometown, Fayetteville, New York. -

Meta-Analysis of the Relationships Between Different Leadership Practices and Organizational, Teaming, Leader, and Employee Outcomes*

Journal of International Education and Leadership Volume 8 Issue 2 Fall 2018 http://www.jielusa.org/ ISSN: 2161-7252 Meta-Analysis of the Relationships Between Different Leadership Practices and Organizational, Teaming, Leader, and Employee Outcomes* Carl J. Dunst Orelena Hawks Puckett Institute Mary Beth Bruder University of Connecticut Health Center Deborah W. Hamby, Robin Howse, and Helen Wilkie Orelena Hawks Puckett Institute * This study was supported, in part, by funding from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (No. 325B120004) for the Early Childhood Personnel Center, University of Connecticut Health Center. The contents and opinions expressed, however, are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy or official position of either the Department or Office and no endorsement should be inferred or implied. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The meta-analysis described in this paper evaluated the relationships between 11 types of leadership practices and 7 organizational, teaming, leader, and employee outcomes. A main focus of analysis was whether the leadership practices were differentially related to the study outcomes. Studies were eligible for inclusion if the correlations between leadership subscale measures (rather than global measures of leadership) and outcomes of interest were reported. The random effects weighted average correlations between the independent and dependent measures were used as the sizes of effects for evaluating the influences of the leadership practices on the outcome measures. One hundred and twelve studies met the inclusion criteria and included 39,433 participants. The studies were conducted in 31 countries in different kinds of programs, organizations, companies, and businesses. -

Education Revolution DOUBLE ISSUE

The Magazine of Alternative Education Education Revolution DOUBLE ISSUE I s s u e N u m b e r T h i r t y S e v e n SUMMER 2003 $4.95 USA/5.95 CDN SAY NO TO HIGH STAKES TESTING FOR KIDS Don’t Miss the IDEC! DETAILS INSIDE! w w w . e d u c a t i o n r e v o l u t i o n . o r g Education Revolution The Magazine of Alternative Educatuion Summer 2003 - Issue Number Thirty Seven - www.educationrevolution.org News What’s an IDEC? The mission of The Education Revolution magazine is based Dana Bennis................................................ 6 on that of the Alternative Education Resource Organization A Harsh Agenda (AERO): “Building the critical mass for the education Paul Wellstone..............................................7 revolution by providing resources which support self- It’s Happening All Over The World............... 7 determination in learning and the natural genius in everyone.” Towards this end, this magazine includes the latest news and David Gribble communications regarding the broad spectrum of educational alternatives: public alternatives, independent and private Being There alternatives, home education, international alternatives, and On the Bounce…………..........................9 more. The common feature in all these educational options is Street Kids……………….........................11 that they are learner-centered, focused on the interest of the child rather than on an arbitrary curriculum. Mail & Communication AERO, which produces this magazine quarterly, is firmly Main Section…………………………....... 15 established as a leader in the field of educational alternatives. News of Schools…………………………. 19 Founded in 1989 in an effort to promote learner-centered High Stakes Testing…………………….. -

Progressive Education

PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION Lessons fronn the Past and Present Susan F. Semel, Alan R. Sadovnik, and Ryan W. Coughlan Progressive education is one of the most enduring educational reform move ments in this country, with a lifespan of over one hundred years. Although as noted earlier, it waxes and wanes in popularity, many of its practices now appear so regularly in both private and public schools as to have become almost mainstream. But from the schools that were the pioneers, what useful ■ lessons can we learn? The histories of the early progressive schools profiled in ■part 1 illustrate what happened to some of the progressive schools founded in I jhe first part of the twentieth century. But even now, they serve as important reminders for educators concerned with the competing issues of stability and change in schools with particular progressive philosophies—reminders, spe cifically, of the complex nature of school reform.' As we have seen in these histories, balancing the original intentions of progressive founders with the known demands upon practitioners has been the challenge some of the schools have met successfully and others have not. As contemporary American educators consider the school choice movement, the burgeoning expansion of charter schools, and the growing focus on stan- dards-based testing and accountability measures, they would do well to look back for guidance at some of the original schools representative of the “new education.” Particularly instructive. The Dalton School and The City and 374 SUSAN F. SEMEL ET AL. Country School are both urban independent schools that have enjoyed strong and enduring leaders, well-articulated philosophies and accompanying ped agogic practice, and a neighborhood to supply its clientele. -

Early Steps Celebration 30Th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 the University Club New York, NY

Benefit Early Steps Celebration 30th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 The University Club New York, NY Early Steps 540 East 76th Street • New York, NY 10021 www.earlysteps.org • 212.288.9684 Horace Mann School and all of our Early Steps students and families, past and present, join in celebrating Early Steps’ 30 Years as A Voice for Diversity in NYC Independent Schools Letter from our Director Dear Friends, For nearly three decades, it has been my joy and re- sponsibility to guide the parents of children of color through the process of applying to New York City in- dependent schools for kindergarten and first grade, helping them to realize their hopes and dreams for their children. While over 3,500 students of color entered school with the guidance of Early Steps, it is humbling to know that the impact has been so much greater. We hear time and © 2012 Victoria Jackson Photography again how families, schools and lives have been trans- formed as a result of the doors of opportunity that were opened with the help of Early Steps. Doors where academic excellence is the norm and children learn and play with others whose life’s experiences are not the same as theirs, benefitting all children. We are proud of our 30-year partnership with now over 50 New York City independent schools who nurture, educate and challenge our children to be the best that they can be. They couldn’t be in better hands! Tonight we honor four Early Steps alumni. These accomplished young adults all benefited from the wisdom of their parents who knew the importance of providing their children with the best possible education beginning in Kindergarten. -

The Therapeutic Community As an Adaptable Treatment Modality Across Different Settings

P1: KEG Psychiatric Quarterly [psaq] ph259-psaq-482367 June 3, 2004 10:30 Style file version June 4th, 2002 Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 3, Fall 2004 (C 2004) THE THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY AS AN ADAPTABLE TREATMENT MODALITY ACROSS DIFFERENT SETTINGS David Kennard Simple core statements of the therapeutic community as a treatment modal- ity are given, including a “living-learning situation” and “culture of enquiry.” Applications are described in work with children and adolescents, chronic and acute psychoses, offenders, and learning disabilities. In each area the evolu- tion of different therapeutic community models is outlined. In work with young people the work of Homer Lane and David Wills is highlighted. For long term psychosis services, the early influence of “moral treatment” is linked to the revitalisation of asylums and the creation of community based facilities; acute psychosis services have been have been run as therapeutic communities in both hospital wards and as alternatives to hospitalisation. Applications in prison are illustrated through an account of Grendon prison. The paper also outlines the geographical spread of therapeutic communities across many countries. KEY WORDS: therapeutic communities; children; psychosis; prison; learning disability. The author is Head of Psychological Services, The Retreat, York, England. Address correspondence to David Kennard, The Retreat, York, YO10 5BN, United Kingdom; e-mail: [email protected]. 295 0033-2720/04/0900-0295/0 C 2004 Human Sciences Press, Inc. P1: KEG Psychiatric Quarterly [psaq] ph259-psaq-482367 June 3, 2004 10:30 Style file version June 4th, 2002 296 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY This is a paper about different adaptations of the basic therapeutic community idea. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

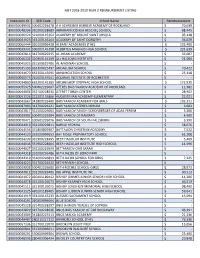

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Serious Educational Game Assessment

Serious Educational Game Assessment Serious Educational Game Assessment Serious Educational Practical Methods and Models for Educational Games, Simulations and Virtual Worlds Game Assessment Leonard Annetta George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA Practical Methods and Models for and Educational Games, Simulations and Stephen Bronack (Eds.) Virtual Worlds Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, USA In an increasingly scientifi c and technological world the need for a knowledgeable citizenry, individuals who understand the fundamentals of technological ideas and think Leonard Annetta and Stephen Bronack (Eds.) critically about these issues, has never been greater. There is growing appreciation across the broader education community that educational three dimensional virtual learning environments are part of the daily lives of citizens, not only regularly occurring in schools and in after-school programs, but also in informal settings like museums, science centers, zoos and aquariums, at home with family, in the workplace, during leisure time when children and adults participate in community-based activities. This blurring of the boundaries of where, when, why, how and with whom people learn, along with better understandings of learning as a personally constructed, life-long process of making meaning and shaping identity, has initiated a growing awareness in the fi eld that the questions and frameworks guiding assessing these environments (Eds.) Bronack Stephen and Annetta Leonard should be reconsidered in light of these new realities. The audience for this book will be researchers working in the Serious Games arena along with distance education instructors and administrators and students on the cutting edge of assessment in computer generated environments. S e n s e P u b l i s h e r s DIVS SensePublishers Serious Educational Game Assessment Serious Educational Game Assessment Practical Methods and Models for Educational Games, Simulations and Virtual Worlds Edited by Leonard Annetta George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA Stephen C. -

Teaching in the University

Educational Foundations,David Hursh Summer 2003 Imagining the Future: Growing Up Working Class; Teaching in the University By David Hursh I never wanted to be a teacher. In school I constantly counted the minutes until the last bell, when I would be free to join the other boys playing whichever sport the season demanded. I measured my success not by test grades but by touchdowns and runs scored. Therefore, I am surprised that for the last thirty years I have been teaching. But it is in teaching, in the crucible of the classroom, that one can engage in asking ques- tions and making sense of one another and the world. It is in the classroom in which a gaggle of five and six year olds responded to my question of how the Grand Can- yon was formed with the unexpected but understand- able explanation of earthquakes and tornadoes. And it is in last night’s classroom of doctoral students — mostly teachers and administrators — in which we David Hursh is an associate professor deliberated over the effect that the current testing move- in the Warner Graduate School of ment has on our ability to engage students in making Education and Human Development sense of ourselves and the world. at the University of Rochester, How then did I move from being a working-class Rochester, New York. boy who experienced school as a digression from my 55 Imagining the Future real interest — sports — to someone who had made education his life work? In this paper I will describe my own understanding of the process. -

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth © 2012 PM Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978–1–60486–484–7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927981 Cover: John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com contents Introduction 1 Robert H. Haworth Section I Anarchism & Education: Learning from Historical Experimentations Dialogue 1 (On a desert island, between friends) 12 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 1 Anarchism, the State, and the Role of Education 14 Justin Mueller chapteR 2 Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools 32 David Gabbard ChapteR 3 Educate, Organize, Emancipate: The Work People’s College and The Industrial Workers of the World 47 Saku Pinta cHAPteR 4 From Deschooling to Unschooling: Rethinking Anarchopedagogy after Ivan Illich 69 Joseph Todd Section II Anarchist Pedagogies in the “Here and Now” Dialogue 2 (In a crowded place, between strangers) 88 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 5 Street Medicine, Anarchism, and Ciencia Popular 90 Matthew Weinstein cHAPteR 6 Anarchist Pedagogy in Action: Paideia, Escuela Libre 107 Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan cHAPteR 7 Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free Skool 124 Jeffery Shantz cHAPteR 8 The Nottingham Free School: Notes Toward a Systemization of Praxis 145 Sara C.