Nahuatl: the Influence of Spanish on the Language of the Aztecs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Historical Journal

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title "May They Not Be Fornicators Equal to These Priests": Postconquest Yucatec Maya Sexual Attitudes Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9wm6k90j Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 12(0) ISSN 0276-864X Authors Restall, Matthew Sigal, Pete Publication Date 1992 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California "May They Not Be Fornicators Equal to These Priests": Postconquest Yucatec Maya Sexual Attitudes^ Matthew Restall and Pete Sigal ten cen ah hahal than cin iialic techex hebaxile a uohelex yoklal P^^ torres p^ Dias cabo de escuadra P^ granado sargento yetel p^ maldonado layoh la ma hahal caput sihil ma hahal confisar ma hahal estremacion ma hahal misa cu yalicobi maix tan u yemel hahal Dios ti lay ostia licil u yalicob misae tumenel tutuchci u cepob sansamal kin chenbel u chekic iieyob cu tuculicob he tu yahalcabe manal tuil u kabob licil u baxtic u ueyob he p^ torrese chenbel u pel kakas cisin Rita box cu baxtic y u moch kabi mai moch u cep ualelob ix >oc cantiil u mehenob ti lay box cisin la baixan p^ Diaz cabo de escuadra tu kaba u cumaleil antonia aluarado xbolonchen tan u lolomic u pel u cumale tiitan tulacal cah y p^ granado sargento humab akab tan u pechic u pel manuela pacheco hetun p^ maldonadoe tun>oc u lahchekic u mektanilobe uay cutalel u chucbes u cheke yohel tulacal cah ti cutalel u ah semana uinic y xchup ti pencuyute utial yoch pelil p^ maldonado xpab gomes u kabah chenbel Padresob ian u sipitolal u penob matan u than yoklalob uaca u ment utzil 92 Indigenous Writing in the Spanish Indies mageuale tusebal helelac ium cura u >aic u tzucte hetun lae tutac u kabob yetel pel lay yaxcacbachob tumen u pen cech penob la caxuob yal misa bailo u yoli Dios ca oc inglesob uaye ix ma aci ah penob u padreilobi hetun layob lae tei hunima u topob u yit uinicobe yoli Dios ca haiac kak tu pol cepob amen ten yumil ah hahal than. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī PART Ī Ī ONE Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī Ī © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-51840-6 - An Introduction to Classical Nahuatl Michel Launey Excerpt More information PRELIMINARY LESSON Phonetics and Writing S ince the time of the conquest, Nahuatl has been written by means of theLatinalphabet.Thereis,therefore,alongtraditiontowhichitis preferable to conform for the most part. Nonetheless, for the following reasons, somewordsinthisbookarewritteninanorthographythatdiffersfromthe traditional one. ̈ Theorthographyis,ofcourse,“hispanicized.”Torepresentthephoneticele- ments of Nahuatl, the letters or combinations of letters that represent identical or similar sounds in Spanish are used. Hence, there is no problem with the sounds that exist in both languages, not to mention those that are lacking in Nahuatl (b, d, g, r etc.). On the other hand, those that exist in Nahuatl but not inSpanisharefoundinalternatespellings,orareevenaltogetherignored.In particular, this is the case with vowel length and (even worse) with the glottal stop (see Table 1.1), which are systematically marked only by two grammar- ians, Horacio Carochi and Aldama y Guevara, and in a text named Bancroft Dialogues.1 ̈ This defective character is heightened by a certain fluctuation because the orthography of Nahuatl has never really been fixed. Hence, certain texts represent the vowel /i/ indifferently with i or j, others always represent it with i but extend this spelling to consonantal /y/, that is, to a differ- ent phoneme. -

The Impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States∗

The impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States∗ John M. Lipski The Pennsylvania State University My charge today is to speak of the impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States. While I have spent more than forty years listening to, studying, and analyzing the Spanish language as used in the United States, I readily confess that the Mexican Revolution was not foremost in my thoughts for many of those years. My life has not been totally without revolutionary influence, however, since in my previous job, at the University of New Mexico, our department had revised its bylaws to reflect the principles of sufragio universal y no reelección. When I began to reflect on the full impact of the Mexican Revolution on U. S. Spanish, I immediately thought of the shelf-worn but not totally irrelevant joke about the student who prepared for his biology test by learning everything there was to know about frogs, one of the major topics of the chapter. When the day of the exam arrived, he discovered to his chagrin that the essay topic was about sharks. Deftly turning lemons into lemonade, he began his response: “Sharks are curious and important aquatic creatures bearing many resemblances to frogs, which have the following characteristics ...”, which he then proceeded to name. The joke doesn’t mention what grade he received for his effort. For the next few minutes I will attempt a similar maneuver, making abundant use of what I think I already know, hoping that you don’t notice what I know that I don’t know, and trying to get a passing grade at the end of the day. -

Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?

investigations | jeffrey m. pilcher WWasas thethe TacoTaco InventedInvented iinn SSouthernouthern CCalifornia?alifornia? Taco bell provides a striking vision of the future trans- literally shape social reality, and this new phenomenon formation of ethnic and national cuisines into corporate that the taco signified was not the practice of wrapping fast food. This process, dubbed “McDonaldization” by a tortilla around morsels of food but rather the informal sociologist George Ritzer, entails technological rationaliza- restaurants, called taquerías, where they were consumed. tion to standardize food and make it more efficient.1 Or as In another essay I have described how the proletarian taco company founder Glen Bell explained, “If you wanted a shop emerged as a gathering place for migrant workers from dozen [tacos]…you were in for a wait. They stuffed them throughout Mexico, who shared their diverse regional spe- first, quickly fried them and stuck them together with a cialties, conveniently wrapped up in tortillas, and thereby toothpick. I thought they were delicious, but something helped to form a national cuisine.4 had to be done about the method of preparation.”2 That Here I wish to follow the taco’s travels to the United something was the creation of the “taco shell,” a pre-fried States, where Mexican migrants had already begun to create tortilla that could be quickly stuffed with fillings and served a distinctive ethnic snack long before Taco Bell entered the to waiting customers. Yet there are problems with this scene. I begin by briefly summarizing the history of this food interpretation of Yankee ingenuity transforming a Mexican in Mexico to emphasize that the taco was itself a product peasant tradition. -

Saltillo Street Names Index: Autumn Gleen Dr

M R - 6 - E R R - 5 - E C c 1 2 3 D 4 5 6 7 U C S D A T R . E R D L 6 . 8 E 3 Y SNER ST. RD 2446 MES SALTILLO STREET NAMES INDEX: AUTUMN GLEEN DR. E3 OLD HWY. 51 E3 A BAUHAUS DR. E3 OLD NATCHEZ TRACE TRAIL G3 BENT GRASS CIR. H2 OLD SALTILLO RD. E4, F4, F5, G5, H4, H5 A BERCH TREE DR. F4 OLD SOUTH PLANTATION DR. E2 R D BIG HARPE TRAIL G2 OLIVIA CV. D4 BIRMINGHAM RIDGE RD. F1, F2, G3 7 PARKRIDGE DR, F4 8 3 BOLIVAR CIR. G3 PATTERSON CIR. E5 . D BOSTIC AVE. E4 PECAN DR. D5 R BRIDLE CV. E3 PETE AVE. F3 D U BRISCOE ST. E4 PEYTON LN. D4 H BROCK DR. F3 33 35 35 35 PINECREST ST. E4 ST 32 32 33 TOWERY . CARTWRIGHT AVE. E4 PINEHURST AVE. E4 31 36 31 R 4 3 D 3 2 CHAMPIONS CV. H2 PINEWOOD ST. E4 5 6 5 4 CHERRY HILL DR. C4 POPULARWOOD LN. F4 1 6 9 5 CHESTNUT LN. C4 PRINSTON DR. E3 1 CHICKASAW CIR. G3 PULLTIGHT RD. B4, C4 CHICKASAW TRAIL G3 PYLE DR. E4 CHRISTY WAY C4 QUAIL CREEK RD. E3 CO 653-B H2, H3 RAILROAD AVE. E5 CO 653-D G3 RD 189 F3 CO 2012 E2, E3 RD 251 D2 3 CO 2012 F3 8 RD 521 C1, E2 7 CO 2720 A1 RD 599 C1, C2, D2 D R CO 2720 B1 RD 647 H3 COBBS CV. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

“Spanglish,” Using Spanish and English in the Same Conversation, Can Be Traced Back in Modern Times to the Middle of the 19Th Century

FAMILY, COMMUNITY, AND CULTURE 391 Logan, Irene, et al. Rebozos de la colección Robert Everts. Mexico City: Museo Franz Mayer, Artes de México, 1997. With English translation, pp. 49–57. López Palau, Luis G. Una región de tejedores: Santa María del Río. San Luis Potosí, Mexico: Cruz Roja Mexicana, 2002. The Rebozo Way. http://www.rebozoway.org/ Root, Regina A., ed. The Latin American Fashion Reader. New York: Berg, 2005. SI PANGL SH History and Origins The history of what people call “Spanglish,” using Spanish and English in the same conversation, can be traced back in modern times to the middle of the 19th century. In 1846 Mexico and the United States went to war. Mexico sur- rendered in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. With its surrender, Mexico lost over half of its territory to the United States, what is now either all or parts of the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. The treaty estab- lished that Mexican citizens who remained in the new U.S. lands automatically became U.S. citizens, so a whole group of Spanish speakers was added to the U.S. population. Then, five years later the United States decided that it needed extra land to build a southern railway line that avoided the deep snow and the high passes of the northern route. This resulted in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853. This purchase consisted of portions of southern New Mexico and Arizona, and established the current U.S.-Mexico border. Once more, Mexican citizens who stayed in this area automatically became U.S. -

Configurationality in Classical Nahuatl*

Configurationality in Classical Nahuatl* Jason D. Haugen Oberlin College Abstract: Some classic generativist analyses (Jelinek 1984, Baker 1996) predict that polysynthetic languages should be non-configurational by positing that the arguments of verbs are marked by clitics or affixes and relegating overt NPs/DPs to adjunct positions. Here I argue that the polysynthetic Uto-Aztecan language Classical Nahuatl (CN) was actually configurational. I claim that unmarked VSO order was derived by verb phrase (vP) fronting, from a base-generated structure of SVO. A vP constituent is evidenced by obligatory movement of indefinite object NPs with the vP, as in pseudo noun incorporation analyses given for VOS order in other predicate-initial languages such as Niuean (Polynesian) (Massam 2001) and Chol (Mayan) (Coon 2010). The CN case is interesting to contrast with languages like Chol, which lack head movement, in that the CN word order facts show the hallmarks of vP remnant movement (i.e., the fronting of the verb plus its determinerless NP object into a position structurally higher than the subject), while the actual morphology of the CN verb shows the hallmarks of head movement (including noun incorporation, tense/aspect/mood suffixes, derivational suffixes such as the applicative and causative, and pronominal agreement prefixes marked on the verb). Finally, in regard to the landing site for the fronted predicate, I argue that the placement of CN’s optional clause-introducing particle ca necessitates adopting the split-Comp proposal of Rizzi (1997), as is suggested for Welsh by Roberts (2005). Specifically, I claim for CN that ca is the head of ForceP and that the predicate fronts to a position in the structurally lower Fin(ite)P. -

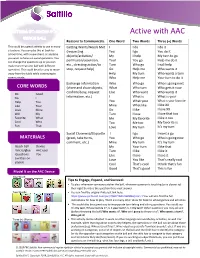

Active with AAC

Active with AAC Reasons to Communicate One Word Two Words Three (+) Words This could be a great activity to use in many Getting Wants/Needs Met I I do I do it situations. You can play this at back-to- (requesting You I go You do it school time, with a new client, or anytime objects/activities/ My I help My turn to go you want to focus on social questions. You can change the questions up or you can permission/attention, Your You go Help me do it make more than one ball with different etc., directing action/to Turn Who go I will help stop, request help) Go Help me Who wants it questions. This could be a fun way to move away from the table while continuing to Help My turn Who wants a turn communicate. Who Help me Your turn to do it Exchange Information Who Who go Who is going next CORE WORDS (share and show objects, What Who turn Who gets it now confirm/deny, request Like Who want Who wants it Do Good Go I information, etc.) I What is What is your Help You You What your What is your favorite Like Your Mine What like I like XX Love Mine Go I like I love XX Will My Turn I love I love that too Favorite What Me My favorite I like it too Cool Who Too Me too My favorite is Fun That Love My turn It’s my turn Social Closeness/Etiquette I I go I want a go MATERIALS (greet, take turns, You Who go Who is going now comment, etc.) Mine My turn It’s my turn Beach ball Device My Your turn I like that Velcro/glue AAC user Turn I like I like it Questions You Like I love I love it (written on Love You like That’s really cool paper) Cool That’s cool I think that’s fun Good That’s good This is fun Model It on the AAC Device One Word: Tips to Engage, Expand, and Succeed: • To play: whenever someone catches the ball, whatever question is touching (or is closest to) their right thumb is the question they must answer. -

Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: a Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California

Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: A Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California Jane H. Hill, William L. Merrill Anthropological Linguistics, Volume 59, Number 1, Spring 2017, pp. 1-23 (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/anl.2017.0000 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/683122 Access provided by Smithsonian Institution (9 Nov 2018 13:38 GMT) Uto-Aztecan Maize Agriculture: A Linguistic Puzzle from Southern California JANE H. HILL University of Arizona WILLIAM L. MERRILL Smithsonian Institution Abstract. The hypothesis that the members of the Proto—Uto-Aztecan speech community were maize farmers is premised in part on the assumption that a Proto—Uto-Aztecan etymon for ‘maize’ can be reconstructed; this implies that cognates with maize-related meanings should be attested in languages in both the Northern and Southern branches of the language family. A Proto—Southern Uto-Aztecan etymon for ‘maize’ is reconstructible, but the only potential cog- nate for these terms documented in a Northern Uto-Aztecan language is a single Gabrielino word. However, this word cannot be identified definitively as cognate with the Southern Uto-Aztecan terms for ‘maize’; consequently, the existence of a Proto—Uto-Aztecan word for ‘maize’ cannot be postulated. 1. Introduction. Speakers of Uto-Aztecan languages lived across much of western North America at the time of their earliest encounters with Europeans or Euro-Americans. Their communities were distributed from the Columbia River drainage in the north through the Great Basin, southern California, the American Southwest, and most of Mexico, with outliers as far south as Panama (Miller 1983; Campbell 1997:133—38; Caballero 2011; Shaul 2014). -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Phonetics and Phonology

46 2 Phonetics and Phonology In this chapter I describe the segmental and suprasegmental categories of CLZ phonology, both how they are articulated and how they fall into the structures of syllable and word. I also deal with phono-syntactic and phono-semantic issues like intonation and the various categories of onomatopoetic words that are found. Other than these last two issues this chapter deals only with strictly phonetic and phonological issues. Interesting morpho-phonological details, such as the details of tonal morphology, are found in Chapters 4-6. Sound files for most examples are included with the CD. I begin in §2.1 and §2.2 by describing the segments of CLZ, how they are articulated and what environments they occur in. I describe patterns of syllable structure in §2.3. In §2.4 I describe the vowel nasalization that occurs in the SMaC dialect. I go on to describe the five tonal categories of CLZ and the main phonetic components of tone: pitch, glottalization and length in §2.5. Next I give brief discussions of stress (§2.6), and intonation (§2.7). During the description of segmental distribution I often mention that certain segments have a restricted distribution and do not occur in some position except in loanwords and onomatopoetic words. Much of what I consider interesting about loanwords has to do with stress and is described in §2.6 but I also give an overview of loanword phonology in §2.8. Onomatopoetic words are sometimes outside the bounds of normal CLZ phonology both because they can employ CLZ sounds in unusual environments and because they may contain sounds which are not phonemic in CLZ.