Myanmar: Time for a Unified Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

↓ Burma (Myanmar)

↓ Burma (Myanmar) Population: 51,000,000 Capital: Rangoon Political Rights: 7 Civil Liberties: 7 Status: Not Free Trend Arrow: Burma received a downward trend arrow due to the largest offensive against the ethnic Karen population in a decade and the displacement of thousands of Karen as a result of the attacks. Overview: Although the National Convention, tasked with drafting a new constitution as an ostensible first step toward democracy, was reconvened by the military regime in October 2006, it was boycotted by the main opposition parties and met amid a renewed crackdown on opposition groups. Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party, remained under house arrest in 2006, and the activities of the NLD were severely curtailed. Meanwhile, a wide range of human rights violations against political activists, journalists, civil society actors, and members of ethnic and religious minority groups continued unabated throughout the year. The military pressed ahead with its offensive against ethnic Karen rebels, displacing thousands of villagers and prompting numerous reports of human rights abuses. The campaign, the largest against the Karen since 1997, had been launched in November 2005. After occupation by the Japanese during World War II, Burma achieved independence from Great Britain in 1948. The military has ruled since 1962, when the army overthrew an elected government that had been buffeted by an economic crisis and a raft of ethnic insurgencies. During the next 26 years, General Ne Win’s military rule helped impoverish what had been one of Southeast Asia’s wealthiest countries. The present junta, led by General Than Shwe, dramatically asserted its power in 1988, when the army opened fire on peaceful, student-led, prodemocracy protesters, killing an estimated 3,000 people. -

Dutch Arms Export Policy in 2018

Dutch Arms Export Policy in 2018 Report by the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation and the Minister of Foreign Affairs on the export of military goods July 2019 Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 3 2. Profile of the Dutch defence industry ....................................................... 4 3. Procedures and principles ....................................................................... 6 3.1 Procedures .............................................................................................................................. 6 3.2 Changes in 2018 ..................................................................................................................... 6 3.3 Principles ................................................................................................................................ 7 4. Transparency in Dutch arms export policy ................................................ 8 4.1 Trade in military goods ........................................................................................................... 8 4.2 Trade in dual-use goods ......................................................................................................... 9 4.3 Procedures .............................................................................................................................. 9 5. Dutch arms export in 2018 .................................................................... 11 6. Relevant developments -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Military & Defense

Power Air Cables Hoses MILITARY & DEFENSE ITW GSE Equipment and Accessories Reliable Technology for Military & Defense Applications THE SMART CHOICE ITW GSE leads the industry in ground support YOU CAN RELY ON US equipment for fighter aircraft. We provide ITW GSE’s manufacturing processes are equipment and accessories with the latest in streamlined to ensure homogeneous products technology and innovation including clean and based on quality components. Therefore, we can green battery powered units. offer highly reliable products and fast delivery ITW GSE has supported military and defense times. Prior to shipment, all units are fully tested applications worldwide for more than 50 years toand inspected to ensure you are receiving the include the most advanced fighter platforms suchoptimum quality. as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, F-16 Falcon, F-18 Hornet, F-15 Eagle, F-22A Raptor, the T-50 and C-130 and more. We also supply equipment for UAV and UAS. Our products are dependable, of high quality, easy to operate and maintain. MILITARY STANDARDS WITH As an ITW company (Illinois Tool Works Inc.), we MAXIMUM PERSONAL SAFETY have a unique way of doing business, and financial Our units meet and exceed MIL-STD-704E and they strength you can depend on. At our core is the can operate under harsh climatic conditions - from talent and dedication of our people. We focus on the very cold surroundings in Alaska till the hot what we do best, and we strive to do it better than conditions of the Middle East. They can be equipped anyone else. We share knowledge, and we learn with military interlock and other features as well. -

World Air Forces 2018 in Association with 1 | Flightglobal

WORLD AIR FORCES 2018 IN ASSOCIATION WITH 1 | FlightGlobal Umschlag World Air Forces 2018.indd Alle Seiten 16.11.17 14:23 WORLD AIR FORCES Directory Power players While the new US president’s confrontational style of international diplomacy stoked rivalries, the global military fleet saw a modest rise in numbers: except in North America CRAIG HOYLE LONDON ground-attack aircraft had been destroyed, DATA COMPILED BY DARIA GLAZUNOVA, MARK KWIATKOWSKI & SANDRA LEWIS-RICE Flight Fleets Analyzer shows the action as hav- DATA ANALYSIS BY ANTOINE FAFARD ing had limited materiel effect. It did, however, draw Russia’s ire, as a detachment of its own rinkmanship was the name of the of US Navy destroyers launched 59 Raytheon combat aircraft was using the same Syrian base. game for much of the 2017 calendar Tomahawk cruise missiles towards Syria’s Al- Another spike in rhetoric came in mid-June, year, with global tensions in no small Shayrat air base, targeting its runways and hard- when a Syrian Su-22 was shot down by a US part linked to the head-on approach ened aircraft shelters housing Sukhoi Su-22s. Navy Boeing F/A-18E Super Hornet after attack- B to diplomacy taken by US President Don- Despite initial claims from the Pentagon that ing opposition forces backed by Washington. ald Trump. about one-third of its more than 40 such Syria threatened to target US combat aircraft Largely continuing with the firebrand with advanced surface-to-air missile systems in soundbites which brought him to the Oval Of- Trump and Kim Jong-un the wake of the incident. -

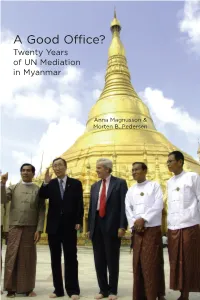

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

Prologue This Report Is Submitted Pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264)

Prologue This report is submitted pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264). Section 4 of this law provides, in part, that: ―The President shall from time to time as occasion may require, but not less than once each year, make reports to the Congress of the activities of the United Nations and of the participation of the United States therein.‖ In July 2003, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the authority to transmit this report to Congress. The United States Participation in the United Nations report is a survey of the activities of the U.S. Government in the United Nations and its agencies, as well as the activities of the United Nations and those agencies themselves. More specifically, this report seeks to assess UN achievements during 2007, the effectiveness of U.S. participation in the United Nations, and whether U.S. goals were advanced or thwarted. The United States is committed to the founding ideals of the United Nations. Addressing the UN General Assembly in 2007, President Bush said: ―With the commitment and courage of this chamber, we can build a world where people are free to speak, assemble, and worship as they wish; a world where children in every nation grow up healthy, get a decent education, and look to the future with hope; a world where opportunity crosses every border. America will lead toward this vision where all are created equal, and free to pursue their dreams. This is the founding conviction of my country. It is the promise that established this body. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

0218-DG-Defnews-Asian-Fighter

ASIA FIGHTER REVIEW Asia Fighter Review Singapore shops for new platforms as part of Air Force transformation BY MIKE YEO ly completed taking delivery of 40 Boeing F-15SG [email protected] Strike Eagle multirole fighters, which serve alongside other aircraft and helicopters such as MELBOURNE, Australia — The Republic of Sin- Lockheed Martin F-16C/D Block 52/52+ Fighting gapore Air Force celebrates its 50th anniversary Falcons and Boeing AH-64D Apache helicopter this year as it continues its transformation into gunships. a modern fighting force, with the service due to The Air Force will also start taking delivery of take delivery of new platforms this year amid a the first of six Airbus A330 Multi-Role Tanker number of ongoing procurement programs. Transports, which will replace four ex-U.S. Air The Southeast Asian island nation — which Force KC-135 Stratotankers acquired in the late measures roughly one-third the size of the U.S. 1990s along with five Lockheed Martin KC-130B/H state of Rhode Island in terms of land area and Hercules tankers/transports, which have now is strategically located at the southern end of the gone back to serve as airlifters in Singapore’s Air Straits of Malacca, through which a significant Force alongside five C-130Hs. portion of the world’s maritime trade passes — The service is also expected to receive two is a security cooperation partner of the United Lockheed Martin S-70B Seahawk anti-submarine States and operates one of the most advanced helicopters this year, bringing its fleet to eight. -

The Generals Loosen Their Grip

The Generals Loosen Their Grip Mary Callahan Journal of Democracy, Volume 23, Number 4, October 2012, pp. 120-131 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/jod.2012.0072 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jod/summary/v023/23.4.callahan.html Access provided by Stanford University (9 Jul 2013 18:03 GMT) The Opening in Burma the generals loosen their grip Mary Callahan Mary Callahan is associate professor in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She is the author of Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma (2003) and Political Authority in Burma’s Ethnic Minority States: Devolution, Occupation and Coexistence (2007). Burma1 is in the midst of a political transition whose contours suggest that the country’s political future is “up for grabs” to a greater degree than has been so for at least the last half-century. Direct rule by the mili- tary as an institution is over, at least for now. Although there has been no major shift in the characteristics of those who hold top government posts (they remain male, ethnically Burman, retired or active-duty mili- tary officers), there exists a new political fluidity that has changed how they rule. Quite unexpectedly, the last eighteen months have seen the retrenchment of the military’s prerogatives under decades-old draconian “national-security” mandates as well as the emergence of a realm of open political life that is no longer considered ipso facto nation-threat- ening. Leaders of the Tatmadaw (Defense Services) have defined and con- trolled the process. -

List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly

Sixty-seventh session of the General Assembly To convene on United Nations 18 September 2012 List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly Session Year Name Country Sixty-seventh 2012 Mr. Vuk Jeremić (President-elect) Serbia Sixty-sixth 2011 Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser Qatar Sixty-fifth 2010 Mr. Joseph Deiss Switzerland Sixty-fourth 2009 Dr. Ali Abdussalam Treki Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2009 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-third 2008 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-second 2007 Dr. Srgjan Kerim The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixty-first 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixtieth 2005 Mr. Jan Eliasson Sweden Twenty-eighth special 2005 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Fifty-ninth 2004 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2004 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia (resumed twice) 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-eighth 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-seventh 2002 Mr. Jan Kavan Czech Republic Twenty-seventh special 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea (resumed) 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Fifty-sixth 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Twenty-sixth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fifth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Fifty-fifth 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fourth special 2000 Mr. Theo-Ben Gurirab Namibia Twenty-third special 2000 Mr.