Futurism, We Want

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futurism's Photography

Futurism’s Photography: From fotodinamismo to fotomontaggio Sarah Carey University of California, Los Angeles The critical discourse on photography and Italian Futurism has proven to be very limited in its scope. Giovanni Lista, one of the few critics to adequately analyze the topic, has produced several works of note: Futurismo e fotografia (1979), I futuristi e la fotografia (1985), Cinema e foto- grafia futurista (2001), Futurism & Photography (2001), and most recently Il futurismo nella fotografia (2009).1 What is striking about these titles, however, is that only one actually refers to “Futurist photography” — or “fotografia futurista.” In fact, given the other (though few) scholarly studies of Futurism and photography, there seems to have been some hesitancy to qualify it as such (with some exceptions).2 So, why has there been this sense of distacco? And why only now might we only really be able to conceive of it as its own genre? This unusual trend in scholarly discourse, it seems, mimics closely Futurism’s own rocky relationship with photography, which ranged from an initial outright distrust to a later, rather cautious acceptance that only came about on account of one critical stipulation: that Futurist photography was neither an art nor a formal and autonomous aesthetic category — it was, instead, an ideological weapon. The Futurists were only able to utilize photography towards this end, and only with the further qualification that only certain photographic forms would be acceptable for this purpose: the portrait and photo-montage. It is, in fact, the very legacy of Futurism’s appropriation of these sub-genres that allows us to begin to think critically about Futurist photography per se. -

Caffeina E Vodka Italia E Russia: Futurismi a Confronto Claudia Salaris

Caffeina e vodka Italia e Russia: futurismi a confronto Claudia Salaris Il viaggio di Marinetti in Russia Negli anni eroici del futurismo il fondatore Filippo Tommaso Marinetti era noto con il soprannome di “Caffeina d’Europa” per l’energia con cui diffondeva la religione del futuro da un paese all’altro. Uno dei suoi viaggi memorabili è quello in Russia all’inizio del 1914 1. Invitato a tenere un ciclo di conferenze a Mosca e a Pietroburgo, Il poeta ha accettato con entusiasmo, pensando a un patto d’unità d’azione con i fratelli orientali. Infatti nella terra degli zar il futurismo è nato con caratteristiche proprie,ma è sempre un parente stretto del movimento marinettiano. Nelle realizzazioni dell’avanguardia russa non sono pochi gli echi delle teorie e invenzioni del futurismo marinettiano. Ma, al contrario degli italiani che formano una specie di partito d’artisti omogeneo, i russi sono sparsi in diversi gruppi. Nel 1910 è uscita a Pietroburgo l’antologia Il vivaio dei giudici , a cui hanno collaborato, tra gli altri, i fratelli David e Nikolaj Burljuk, Elena Guro, Vasilij Kamenskij, Viktor Chlebnikov. A costoro presto si sono uniti Vladimir Majakovskij, Benedikt Livshich, Alexandr Kruchënych e alla fine del 1912 il gruppo, che intanto ha assunto il nome di Gileja, pubblica il volume Schiaffo al gusto corrente , che nel titolo rivela la matrice marinettiana, ricalcando il “disprezzo del pubblico” promulgato dal poeta italiano. Il libro collettivo contiene un editoriale-manifesto in cui i gilejani, rifiutando il passato e le accademie, esortano i giovani a “gettare Pushkin, Dostoevskij, Tolstoj, ecc. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

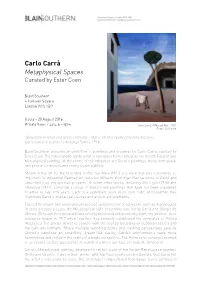

Carlo Carrà Metaphysical Spaces Curated by Ester Coen

Carlo Carrà Metaphysical Spaces Curated by Ester Coen Blain|Southern 4 Hanover Square London W1S 1BP 8 July – 20 August 2016 Private View: 7 July, 6 – 8pm Carlo Carrà, Il Pino sul Mare, 1921 Private Collection ’Simplicity in tonal and linear relations - that is all that really concerns me now.’ Carlo Carrà in a letter to Ardengo Soffici, 1916 Blain|Southern presents an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Carlo Carrà, curated by Ester Coen. The Italian avant-garde artist is renowned for his integral role in both Futurist and Metaphysical painting. At the centre of the exhibition are Carrà’s paintings, many from public and private collections and rarely shown publicly. Shown in the UK for the first time Il Pino Sul Mare (1921) is a work that was considered so important by influential German art historian Wilhelm Worringer that he wrote to Carrà and described it as ‘my spiritual property’. A dozen other works, including Mio Figlio (1916) and Penelope (1917), comprise a group of Carrà’s key paintings that have not been presented together in over fifty years. Each is a significant work in its own right, and together they illuminate Carrà’s intellectual journey and artistic achievements. Typified by dream-like views and unexpected juxtapositions of elements, such as mannequins in eerie arcaded piazzas, the Metaphysical style of painting was led by Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. Although their investigations initially developed independently from one another, their discourse began in 1917 when together they formally established the principles of Pittura Metafisica. The artists strived to connect with the soul by focussing on quotidian objects and the built environment. -

Federico Luisetti, “A Futurist Art of the Past”, Ameriquests 12.1 (2015)

Federico Luisetti, “A Futurist Art of the Past”, AmeriQuests 12.1 (2015) A Futurist Art of the Past: Anton Giulio Bragaglia’s Photodynamism Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Un gesto del capo1 Un gesto del capo (A gesture of the head) is a rare 1911 “Photodynamic” picture by Anton Giulio Bragaglia (1890-1960), the Rome-based photographer, director of experimental films, gallerist, theater director, and essayist who played a key role in the development of the Italian Avant- gardes. Initially postcard photographs mailed out to friends, Futurist Photodynamics consist of twenty or so medium size pictures of small gestures (greeting, nodding, bowing), acts of leisure, work, or movements (typing, smoking, a slap in the face), a small corpus that preceded and influenced the experimentations of European Avant-garde photography, such as Christian Schad’s Schadographs, Man Ray’s Rayographs, and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy’s Photograms. Thanks to historians of photography, in particular Giovanni Lista and Marta Braun, we are familiar with the circumstances that led to the birth of Photodynamism, which took on and transformed the principles proclaimed in the April 11, 1910 Manifesto tecnico della pittura futurista (Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting) by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini, where the primacy of movement and the nature of “dynamic sensation” challenge the conventions of traditional visual arts: “The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be 1 (A Gesture of the Head), 1911. Gelatin silver print, 17.8 x 12.7 cm, Gilman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia's Futurism Writing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian By Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 © Copyright by Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War By Adriana Marie Baranello Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Lucia Re, Co-Chair Professor Claudio Fogu, Co-Chair Fillia (Luigi Colombo, 1904-1936) is one of the most significant and intriguing protagonists of the Italian futurist avant-garde in the period between the two World Wars, though his body of work has yet to be considered in any depth. My dissertation uses a variety of critical methods (socio-political, historical, philological, narratological and feminist), along with the stylistic analysis and close reading of individual works, to study and assess the importance of Fillia’s literature, theater, art, political activism, and beyond. Far from being derivative and reactionary in form and content, as interwar futurism has often been characterized, Fillia’s works deploy subtler, but no less innovative forms of experimentation. For most of his brief but highly productive life, Fillia lived and worked in Turin, where in the early 1920s he came into contact with Antonio Gramsci and his factory councils. This led to a period of extreme left-wing communist-futurism. In the mid-1920s, following Marinetti’s lead, Fillia moved toward accommodation with the fascist regime. This shift to the right eventually even led to a phase ii dominated by Catholic mysticism, from which emerged his idiosyncratic and highly original futurist sacred art. -

Aksenov BOOK

Other titles in the Södertörn Academic Studies series Lars Kleberg (Stockholm) is Professor emeritus of Russian at Södertörn University. He has published numerous Samuel Edquist, � �uriks fotspår: �m forntida svenska articles on Russian avant-garde theater, Russian and österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Polish literature. His book �tarfall: � �riptych has been translated into fi ve languages. In 2010 he published a Jonna Bornemark (ed.), �henomenology of �ros, 2012. literary biography of Anton Chekhov, �jechov och friheten Jonna Bornemark and Hans Ruin (eds.), �mbiguity of ([Chekhov and Freedom], Stockholm: Natur & Kultur). the �acred, forthcoming. Aleksei Semenenko (Stockholm) is Research fellow at Håkan Nilsson (ed.), �lacing �rt in the �ublic the Slavic Department of Stockholm University. He is the �ealm, 2012. author of �ussian �ranslations of �amlet and �iterary �anon �ormation (Stockholm University, 2007), �he Per Bolin, �etween �ational and �cademic �gendas, �exture of �ulture: �n �ntroduction to �uri �otman’s forthcoming. �emiotic �heory (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), and articles on Russian culture, translation and semiotics. Ларс Клеберг (Стокгольм) эмерит-профессор Седертoрнского университета, чьи многочисленные публикации посвящены театру русского авангарда и русской и польской литературе. Его книга Звездопад. Триптих была переведена на пять языков. В 2010 году вышла его биография А. П. Чехова �jechov och friheten [«Чехов и свобода»]. Алексей Семененко (Стокгольм) научный сотрудник Славянского института Стокгольмского университета, автор монографий �ussian �ranslations of �amlet and �iterary �anon �ormation и �he �exture of �ulture: �n �ntroduction to �uri �otman’s �emiotic �heory, а также работ по русской культуре, переводу и семиотике. Södertörns högskola [email protected] www.sh.se/publications Other titles in the Södertörn Academic Studies series Lars Kleberg (Stockholm) is Professor emeritus of Russian at Södertörn University. -

Willi Baumeister International Willi Baumeister and European Modernity 1920S–1950S

Willi Baumeister International Willi Baumeister and European Modernity 1920s–1950s November 21, 2014 — March 29, 2015 Works by Willi Baumeister 1909–1955. Works from the Baumeister Collection by Josef Albers, Hans Arp, Julius Bissier, Georges Braques, Carlo Carrà, Marc Chagall, Albert Gleizes, Roberta González, Camille Graeser, Hans Hartung, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Krause, Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger, El Lissitzky, August Macke, Otto Meyer-Amden, Joan Miró, László Moholy-Nagy, Amédée Ozenfant, Pablo Picasso, Oskar Schlemmer, Kurt Schwitters, Michel Seuphor, Gino Severini, Zao Wou-Ki From the Daimler Art Collection: Hans Arp, Willi Baumeister, Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Otto Meyer-Amden, Oskar Schlemmer, Georges Vantongerloo Daimler Contemporary Berlin Potsdamer Platz Berlin Introduction Renate Wiehager Stuttgart artist Willi Baumeister (1889–1955) is one of the The collection comprises, among others, paintings by Wassily From the outset the Daimler Art Collection has, in both its most important German artists of the postwar period and Kandinsky, Hans Arp, Fernand Léger, and Kazimir Malevich. conception and its aims, gone well beyond mere corporate- among the most significant representatives of abstract paint- The focus of the exhibition is on central groups of works by image enhancement. In fact, over the years the collection ing. His influence as an avant-garde artist, as a professor at Willi Baumeister, ranging from his constructivist phase to the has become one of the leading European Corporate Collec- the School of Decorative Arts in Frankfurt am Main and after Mauerbilder and the late Montaru paintings as well as the tions and a living part of the corporation. Since it was inau- 1946 at the Stuttgart Academy, and as a major art theoreti- Afrika series. -

Alexandra Exter's Dynamic City in 1913

GEORGII KOVALENKO Alexandra Exter’s Dynamic City in 1913 Georgii Kovalenko is a Doctor of Art History, head of the Department of 20th century Russian Art at the Research Institute of the Theory and History of Fine Arts at the Russian Academy of Art, and the lead scientist at the State Institute of Art History. He is the deputy chairman of the Commission for the Study of Avant-Garde Art of the 1910s and 1920s at the Russian Academy of Sciences, as well as the editor of the series h!VANT 'ARDE!RTOFTHESANDSvINVOLUMES ANDh2USSIAN !RTTH#ENTURYvINVOLUMES (ISPUBLICATIONSINCLUDEAlexandra Exter – Farbrhytthmen (State Russian Museum, 2001) and iÝ>`À>Ê ÝÌiÀÊUÊÊ Retrospective (Moscow Museum of Modern Art, 2010). 34 Alexandra Exter painted one night landscape after into it, demanding to be remembered, as if in another minute another. Night time streets, buildings with darkened it will change unrecognizably, disappear, go out and be carried windows, deep shadows on gleaming sidewalks and sharp rays away along with the frantically flying lights. diverging in a cone shape – light from streetlamps and from car headlights, tram lights. Exter sometimes indicated the relevant city in the titles of her works – Kiev (Fundakleyevskaya Street), Florence – but more often it is just City at Night, just Night Time City. And geographical details add little, in essence, to the painting: speaking generally we are looking at one and the same city. And the important thing is that it is a city at night. And it so resembles the Paris described by Apollinaire: Night of Paris, drunk on gin, Filled with electric light. -

Willi Baumeister International Willi Baumeister and European Modernity 1920S–1950S

Willi Baumeister international Willi Baumeister and European Modernity 1920s–1950s Works by Willi Baumeister from the years 1909-1955 Supplemented by works of international artists of the time Daimler Contemporary, Potsdamer Platz Berlin November 21, 2014 – March 29, 2015 Works from the Baumeister Collection by Josef Albers, Hans Arp, Julius Bissier, Georges Braques, Carlo Carrà, Marc Chagall, Albert Gleizes, Roberta González, Camille Graeser, Hans Hartung, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Franz Krause, Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger, El Lissitzky, August Macke, Otto Meyer-Amden, Joan Miró, László Moholy-Nagy, Amédée Ozenfant, Pablo Picasso, Oskar Schlemmer, Kurt Schwitters, Michel Seuphor, Gino Severini, Zao Wou-Ki From the Daimler Art Collection: Hans Arp, Willi Baumeister, Max Bill, Camille Graeser, Otto Meyer-Amden, Oskar Schlemmer, Georges Vantongerloo Stuttgart artist Willi Baumeister (1889–1955) is one of the most important German artists of the postwar period and among the most significant representatives of abstract painting. His influence as an avant-garde artist, as a professor at the School of Decorative Arts in Frankfurt am Main and after 1946 at the Stuttgart Academy, and as a major art theoretician could be felt far beyond Germany. From early on, Baumeister was in close contact with French artists and exhibited his works in Italy, Spain, France, and Switzerland. He could seamlessly resume these contacts after the Second World War. The exhibition retraces his international relations to gallerists, collectors and art historians. It will, for the first time, present parts of his private art collection, which he assembled through swapping his own works for paintings by his artist friends. The collection comprises, among others, paintings by Wassily Kandinsky, Hans Arp, Fernand Léger, and Kazimir Malevich. -

Futurism and the Avant-Gardes 329

Futurism and the Avant-Gardes 329 Chapter 16 Futurism and the Avant-Gardes Selena Daly Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded the Futurist movement in 1909, infa- mously celebrating war as the ‘sole cleanser of the world,’1 and in 1911 he spoke of the Futurists’ ‘restless waiting for war.’2 The arrival of the First World War fulfilled their most heartfelt desires but was also a traumatic and transforma- tive event for the avant-garde movement. In Futurist criticism, the years of the First World War were long considered an endpoint to the movement. The so- called ‘heroic’ period of Futurism concluded in 1915/16, with the deaths of two of the movement’s protagonists, the painter Umberto Boccioni and the archi- tect Antonio Sant’Elia, and the distancing of two other key figures, Carlo Carrà and Gino Severini, from Marinetti’s orbit. In 1965, Maurizio Calvesi, one of the pioneers of Futurist criticism, wrote that ‘Futurism is extinguished at its best’ in 1915/16.3 Marianne W. Martin’s foundational study, Futurist Art and Theory, of 1968 also stopped in 1915: she commented that the death of Boccioni and Sant’Elia while serving in the Italian Army and the injuries of Marinetti and Luigi Russolo in 1917 brought ‘their final joint venture to a tragically heroic end.’4 Although today the idea that Futurism ended in 1915 is untenable (the movement would continue in various forms until Marinetti’s death in 1944), the presentation of the First World War as a dramatic conclusion to the move- ment’s first phase has persisted.5 The war has been blamed for ‘destroy[ing] 1 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism (1909),” in Marinetti, Critical Writings, ed. -

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti Correspondence and Papers, 1886-1974, Bulk 1900-1944

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6k4037tr No online items Finding aid for the Filippo Tommaso Marinetti correspondence and papers, 1886-1974, bulk 1900-1944 Finding aid prepared by Annette Leddy. 850702 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti correspondence and papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1974 (bulk 1900-1944) Number: 850702 Creator/Collector: Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso, 1876-1944 Physical Description: 8.5 linear feet(16 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Writer and founder and leader of the Italian Futurist movement. Correspondence, writings, photographs, and printed matter from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's papers, documenting the history of the futurist movement from its beginning in the journal Poesia, through World War I, and less comprehensively, through World War II and its aftermath. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, born in Alexandria in 1876, attended secondary school and university in France, where he began his literary career. After gaining some success as a poet, he founded and edited the journal Poesia (1905), a forum in which the theories of futurism rather quickly evolved. With "Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo," published in Le Figaro (1909), Marinetti launched what was arguably the first 20th century avant-garde movement, anticipating many of the issues of Dada and Surrealism. Like other avant-garde movements, futurism took the momentous developments in science and industry as signaling a new historical era, demanding correspondingly innovative art forms and language.