Smoking Cessation J DG 10, 10 CENTER DR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donnie Swaggart

Plus Regular Postage, Shipping, and Handling. | All prices in The Evangelist are valid through January 31, 2017. For Fast & Easy Ordering Call Toll Free: 1.800.288.8350 (US) | 1.866.269.0109 (CN) or Visit Our Website at www.jsm.org 2 JANUARY 2017 THE EVANGELIST JANUARY 2017 ON THE COVER FEATURES January 2017 | Vol. 51 | No. 1 4 A LAND FLOWING WITH MILK AND HONEY Happy New Year from Jimmy Swaggart Ministries PART IV by Jimmy Swaggart 10 NOT GIVEN TO WINE by Frances Swaggart 14 THE SEVENFOLD PROTECTION OF CHRIST by Donnie Swaggart 18 DEVELOPING A PROPER PRAYER LIFE PART III by Gabriel Swaggart EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 22 YOU CANNOT SEPARATE THE TWO—WHO JIMMY SWAGGART CHRIST IS AND WHAT HE DID EDITOR by Scott Corbin DONNIE SWAGGART STAFF WRITER/EDITOR 38 LIVING IN HIS PRESENCE DESIREE JONES by Loren Larson GRAPHIC DESIGNERS JASON MARK 40 GOD’S ECONOMY PART II by John Rosenstern PHOTOGRAPHY JASON MARK 42 DESIRE IS NOT ENOUGH JAIME TRACY by Mike Muzzerall 44 BORN TO FLY by Dave Smith 46 FROM ME TO YOU by Jimmy Swaggart PRODUCT WARRANTY Jimmy Swaggart Ministries warrants all products for 60 days after the product 7 SonLife Radio Stations & Programming is received. As well, all CDs, DVDs, and other recorded media must be in the original plastic wrap in order to receive a refund. Opened items may 24 SonLife Broadcasting Network only be returned if defective, and then only exchanged for the same product. Programming & TV Stations Jimmy Swaggart Ministries strives to provide the highest quality products 32 2017 Resurrection Campmeeting Schedule and service to our customers. -

Religious Broadcasting in America: a Regulatory History and Consideration of Issues

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1976 Religious Broadcasting in America: A Regulatory History and Consideration of Issues Gary R. Drum University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Drum, Gary R., "Religious Broadcasting in America: A Regulatory History and Consideration of Issues. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1976. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2996 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Gary R. Drum entitled "Religious Broadcasting in America: A Regulatory History and Consideration of Issues." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication. Herbert H. Howard, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Edward Dunn, G. Allen Yeomans Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written .f;y Gary R. Drum entitled ttReligious Broadcasting in America: A Regulatory History and Consideration or Issues." I recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment or the requirements for the degree or Master or Science, with a major in Communications. -

Parish Name E-Mail Editor City, State, ZIP Phone Fax Acadia BAYOU BENGAL LSU [email protected] Van Reed, Acting Editor Eunice, La

Parish Name E-mail Editor City, State, ZIP Phone Fax Acadia BAYOU BENGAL LSU [email protected] Van Reed, Acting Editor Eunice, La. 70535 (337)550-1211 (337)546-6620 Acadia CHURCH POINT NEWS [email protected] Diana Daigle, Editor Church Point, La. 70525 (337)684-5711 (337)684-5793 Acadia CROWLEY POST-SIGNAL [email protected] Harold Gonzales, Editor & Gen Mgr Crowley, La. 70526 (337)783-3450 (337)788-0949 Acadia KAJN-FM [email protected] Steve Cook, News Director Crowley, La. 70527-1469 (337)783-1560 (337)783-1674 Acadia KKOO-FM [email protected] Jerry Methrin, News Director Crowley, La. 70526 (337)783-2520 (337)406-2505 Acadia KQIS-FM [email protected] Philip E. Lizotte, General Manager Crowley, La. 70526 (337)783-2520 (337)783-5744 Acadia KSIG-AM [email protected] Philip E. Lizotte, General Manager Crowley, LA. 70527 (337)783-2520 (337)406-2505 Acadia LOUISIANA FARM & RANCH [email protected] Crowley, La. 70526 (337)788-5151 Acadia RAYNE ACADIAN TRIBUNE [email protected] Paul Kedinger, Editor Rayne, La. 70578 (337)334-3l86 (337)334-8474 Acadia RAYNE INDEPENDENT [email protected] Jo Cart, Editor Rayne, La. 70578 (337)334-2128 (337)334-2120 Allen ALLEN PARISH AD-VANTAGE [email protected] Barbara Doyle, Editor Oakdale, La. 71463 (318)335-0635 (318)335-0431 Allen KINDER COURIER-NEWS [email protected] Mark Leibson, Managing Editor Kinder, La. (337)738-5642 (337)738-5630 Allen OAKDALE JOURNAL [email protected] Barbara Doyle, Editor Oakdale, La. 7l463 (318)335-0635 (318)335-0431 Ascension ASCENSION GIFT GUIDE [email protected] Gail Coco, Editor Gonzales, La. -

The Magazine for TV and FM Dxers

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association DECEMBER 2004 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers TV and FM DXing was never so much Fun! IN THIS ISSUE MAPPING THE JULY 6TH Es CLOUD BOB COOPER’S ARTICLE ON COLOR TV CONTINUES THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, DAVE JANOWIAK AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Dave Janowiak Webmaster: Tim McVey Editorial Staff:, Victor Frank, George W. Jensen, Jeff Kruszka Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Matt Sittel, Doug Smith, Adam Rivers and John Zondlo, Our website: www.anarc.org/wtfda ANARC Rep: Jim Thomas, Back Issues: Dave Nieman, DECEMBER 2004 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email Satellite News… George Jensen 5 address, we now offer a quick, convenient TV News…Doug Smith 6 and secure way to join or renew your FM News…Adam Rivers 14 membership in the WTFDA from our page at: Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 20 Eastern TV DX…Matt Sittel 23 http://fmdx.usclargo.com/join.html Western TV DX…Victor Frank 25 Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 27 Dues are $25 if paid to our Paypal account. Translator News…Bruce Elving 34 But of course you can always renew by check Color TV History…Bob Cooper 37 or money order for the usual price of just $24. -

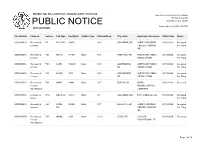

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-200115-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/15/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000096906 Renewal of FX W202BS 93635 88.3 COLUMBIA, MS FAMILY WORSHIP 01/13/2020 Accepted License CENTER CHURCH, For Filing INC. 0000096919 Renewal of FM KBPW 91490 Main 88.1 HAMPTON, AR AMERICAN FAMILY 01/13/2020 Accepted License ASSOCIATION For Filing 0000096966 Renewal of FM KJSB 106689 Main 88.3 JONESBORO, AMERICAN FAMILY 01/13/2020 Accepted License AR ASSOCIATION For Filing 0000096956 Renewal of FM KAOG 1673 Main 90.5 JONESBORO, AMERICAN FAMILY 01/13/2020 Accepted License AR ASSOCIATION For Filing 0000097027 Renewal of FM WKKZ 34942 Main 92.7 DUBLIN, GA KIRBY 01/13/2020 Received License BROADCASTING Amendment COMPANY 0000096860 License To LPD KQFX-LD 56176 Main 30 COLUMBIA, MO NPG of Missouri, LLC 01/13/2020 Accepted Cover For Filing 0000096945 Renewal of FM KJSM- 26390 Main 97.7 AUGUSTA, AR FAMILY WORSHIP 01/13/2020 Accepted License FM CENTER CHURCH, For Filing INC. 0000096954 Renewal of FM WQML 3250 Main 101.5 CEIBA, PR CAGUAS 01/13/2020 Received License EDUCATIONAL TV Amendment Page 1 of 14 REPORT NO. PN-1-200115-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/15/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

FEBRUARY 2020 | Vol

Plus Regular Postage, Shipping, and Handling. | All prices in The Evangelist are valid through February 29, 2020. For Fast & Easy Ordering Call Toll Free: 1.800.288.8350 (US) | 1.866.269.0109 (CN) or Visit Our Website at www.jsm.org Contents FEBRUARY 2020 | Vol. 54 | No. 2 FEATURES The Lord Of The Harvest ...........4 Philosophy And New Age By Jimmy Swaggart Poisons .....................................40 ON THE COVER By John Rosenstern ”That’s what our ministry has been called The Biblical View Of to do from the very beginning—to touch this entire world for the cause of Christ.” Homosexuality, Part I ................10 When Is Truth Not —Evangelist Jimmy Swaggart By Frances Swaggart The Truth? ................................42 By Mike Muzzerall The Responsibility Of Citizenship According What Is Mental To The Bible, Part I ........................ 16 Illness? Part II ...........................44 By Donnie Swaggart By Dave Smith The Bridegroom Cometh, Go From Me To You ......................46 Ye Out To Meet Him, Part II ......20 By Jimmy Swaggart By Gabriel Swaggart Jesus Has More For You ..........36 By Bob Cornell “We are to be a reflection of Jesus Christ in speech and action, hence the Lord’s pronouncement that we are to be ‘salt’ The Way Of Love ......................38 and ‘light.’” By Loren Larson See article on page 16 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Jimmy Swaggart EDITOR Donnie Swaggart GRAPHIC DESIGNER Jason Mark DEPARTMENTS PRODUCTION Shaun Murphy PHOTOGRAPHY Jaime Tracy, Adele Bertoni SonLife Radio Stations 7 ART DIRECTOR Liz Smith SonLife Radio & SonLife Broadcasting Network Programming & TV Stations 24 Letters From The Audience 34 JSM Ministers’ Schedule 50 PRODUCT WARRANTY Jimmy Swaggart Ministries warrants all products for 60 days after the product is received. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

The House That Students Built' Campbell Warns County That Topsoil

J u Aspecialsu |emen i The house that students built' ' pp '«•»sectionc 115th Year, No, 5 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - WEDNESDAY, JUNE 3, 1970 15 CENTS Both political parties show little interest in conventions Only 14 Democrats have filed -Raymond E. Canfield, 2499 N. 4735 W. Grand River, Lansing; for 111 positions as precinct Ovid Rd., Ovid, and Edna M. Kenneth L. Thompson, 9875 delegates, to the Clinton County Austin, 129 W. William St., Ovid. Looking Glassbrook, Grand Democratic Convention. RILEY (3)-Willard Krebel, Ledge, and John R, Ryan, Route Republicans, meanwhile, have 4363 W, Price Rd., St. Johns, 3, Grand Ledge. ~ only 36 candidates for 102 posi VICTOR (3)-None. WESTPHALIA (5)-None. tions at their party's county WATERTOWN (7)-Duane A. ST.JOHNS convention. Woodruff, 7220 Eaton Hwy., Lan First Precinct (4)—Bruce At each party's county con sing; Ernest E, Carter, 14320 Henry Campbell, 207 E. Walker vention, precinct delegates se Airport Rd., Lansing; Lawrence St., St. Johns. lect delegates to attend the state R. Maier, 7380 W. Stoll Rd., Second Precinct (4)—None. SEN. LOCKWOOD convention where delegates to Lansing; Margaret H. Thtngstad, Continued on Page 2A the 1972 national conventions will be chosen. Election of precinct delegates r will be Aug. 4. Lockwood In neither party is there any competition and only the Repub Committee work licans—in five of 29 precincts- makes it have the maximum number of candidates. Democrats have 26 precincts. Josephine Ballenger named officio Delegates may still be elected through write-in votes. A mini mum of three votes is necessary with all deliberate speed He's running for election. -

VHF-UHF Digest

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers September 2015 “Obviously, this station is run by WTFDA members.” - Karl Zuk (Picture from the Student Center at the University of Delaware) A WEAK JULY LEADS TO UNEXPECTED SKIP IN AUGUST MEXICO CONSIDERS ADDING NEW FMs TO MAJOR CITIES DXERS MAKE THEIR LAST CATCHES OF MEXICAN LOW-BAND TVs The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association METEOR SHOWERS INSIDE THIS VUD CLICK TO NAVIGATE Orionids 02 The Mailbox 25 Coast to Coast TV DX OCT 4 - NOV 14 05 TV News 37 Northern FM DX 10 FM News 58 Southern FM DX Leonids 22 Photo News 68 DX Bulletin Board NOVEMBER 5 - 30 THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Ryan Grabow Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Bill Hale, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj Website: www.wtfda.org; Forums: http://forums.wtfda.org September 2015 By now you have probably noticed something familiar in the new column header. It’s back. The graphics have been a little updated but it’s still the same old Mailbox, but it’s also Page Two. -

OF LOU! F for the YEAR 1884

413 JOF THEs—~ D L 7^ 1 OF LOU! f FOR THE YEAR 1884. j§ eventy-fjfecond iSirjniial "ifprarjd ^Communication. A f NEW ORLEANS: A. W. HYATT, 8TAT1ONKR AND PRINTER., 78 CAMP ST.—28038 PROCEEDINGS OP THE ; GRAND LODGE OF THE- STATE OF LOUISIANA FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS. SEVENTY-SECOND ANNUAL GRAND COMMUNICATION, February nth, 12Ik, ijtk and 14th, 1884, A. Li. 5X81. •JAMEh- LOUIS LOBDELL, Grand Master, J. C. BATOHELOR, M. D., Grand Secretary. Publishedbt/ order of the Grand Lodge, and to be read in allthe Lodges. NEW ORLEANS: A. \V. HYATT, STATIONIJB AND PRINTER, 73 OAJtP STBEET—28058 1884:. OFFICE R S MOST WORSHIPFUL GI^D LODGE OF FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS STATE OF LOUISIANA. A. D. 1884. JAMES LOUIS LOBDELL M. W. Or and Master. DAVID RE A GRAHAM 72. W. Deputy Grand Master., CHARLES FRANCIS BUCK B. W. Senior Grand Warden. WILL A. STRONG JR. TV. Junior Grand Warden. ARTHUR \VM. HYATT R. W. Grand Treasurer. JAMES C. BATCHELOR, M. D S. W. Grand Secretary. S. LANDRUM W. Grand Chaplain. F. M. CARAHER TV. Grand Senior Deacon. T. S. JONES W. Grand Junior Deacon. MARK QUAYLE W. Grand Marshal. V. VON SCHOELER W. Grand Sword .Bearer. HENRY HAMBURGER W. Grand Pursuivant. WM. D. MEARNS; TV. Grand Steward. H. W. OGDEN ,.W. Grand Steward. JOHN C. CRIMEN W. Grand Steward. P. M. SCHNEIDAU W. Grand Steward. ALEXANDER Q.UEANT W. Grand Tyler. FIRST DAY'S SESSION. GRAND LODGE HALL, NEW ORLEANS, Monday, February 11, 1884. The Seventy-second Annual Grand Communication of the M. W. G rand Lodge of the State of Louisiana, F. -

List of Radio Stations in Louisiana

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Louisiana From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of Federal Communications Commission–licensed radio stations in the Contents American state of Louisiana, which can be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, Featured content licensees, and programming formats. Current events Random article Contents [hide] Donate to Wikipedia 1 List of radio stations Wikipedia store 2 Defunct 3 See also Interaction 4 References Help 5 Bibliography About Wikipedia Community portal 6 External links Recent changes 7 Images Contact page Tools List of radio stations [edit] What links here This list is complete and up to date as of March 1, 2019. Related changes Upload file Call City of Special pages Frequency Licensee[2][3] Format sign license[1][2] open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com sign license[1][2] Permanent link Page information Spotlight Broadcasting of KAGY 1510 AM Port Sulphur Americana Wikidata item New Orleans, LLC Cite this page KAJD- 96.5 FM Baton Rouge City of Joy, Inc. Urban Gospel Print/export LP Create a book KAJN- 102.9 FM Crowley Agape Broadcasters, Inc. Contemporary Christian Download as PDF FM Printable version Coastal Broadcasting of KANE 1240 AM New Iberia Americana In other projects Lafourche, L.L.C. Wikimedia Commons KAOK 1400 AM Lake Charles Cumulus Licensing LLC News/Talk Languages KAPB- Bontemps Media Services 97.7 FM Marksville Classic country Add links FM LLC American Family KAPI 88.3 FM Ruston Inspirational (AFR) Association American Family KAPM 91.7 FM Alexandria Inspirational (AFR) Association KASO 1240 AM Minden Minden Broadcasting, LLC Classic hits American Family KAVK 89.3 FM Many Inspirational (AFR) Association American Family KAXV 91.9 FM Bastrop Inspirational (AFR) Association KAYT 88.1 FM Jena Black Media Works, Inc. -

1000 Mile Fm Tropo and April E Skip!

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association MAY 2010 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers IN THIS ISSUE! 1000 MILE FM TROPO AND APRIL E SKIP! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org Cover by Paul Mitschler THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info MAY 2010 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 4 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 10 secure way to join or renew your membership Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 14 in the WTFDA from our page at: Eastern TV DX…Nick Langan 15 http://www.wtfda.org/join.html Western TV DX…Nick Langan 16 You can now renew either paper VUD Southern FM DX…John Zondlo 18 membership or your online eVUD membership Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 25 at one convenient stop.