Provo City Corporation V. Donna I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

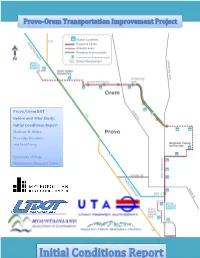

Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report Matthew M

Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report Matthew M. Miller, Mercedes Beaudoin, and Reid Ewing University of Utah, Metropolitan Research Center 2 of 142 Report No. UT‐17.XX PROVO-OREM TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (TRIP) Prepared for: Utah Department of Transportation Research Division Submitted by: University of Utah, Metropolitan Research Center Authored by: Matthew M. Miller, Mercedes Beaudoin, and Reid Ewing Final Report June 2017 ______________________________________________________________________________ Provo/Orem BRT Before and After Study: Initial Conditions Report 3 of 142 DISCLAIMER The authors alone are responsible for the preparation and accuracy of the information, data, analysis, discussions, recommendations, and conclusions presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, endorsements, or policies of the Utah Department of Transportation or the U.S. Department of Transportation. The Utah Department of Transportation makes no representation or warranty of any kind, and assumes no liability therefore. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors acknowledge the Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) for funding this research through the Utah Transportation Research Advisory Council (UTRAC). We also acknowledge the following individuals from UDOT for helping manage this research: Jeff Harris Eric Rasband Brent Schvanaveldt Jordan Backman Gracious thanks to our paid peer reviewers in the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Brigham Young University: Dr. Grant G. Schultz, Ph.D., P.E., PTOE. Dr. Mitsuru Saito, Ph.D, P.E., F. ASCE, F. ITE While not authors, the efforts of the following people helped make this report possible. Data Collection Proof Reading/Edits Ethan Clark Ray Debbie Weaver Thomas Cushing Clint Simkins Jack Egan Debolina Banerjee Katherine A. -

Department of Transportation

Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Denver Airports District Office DRAFT SECTION 303(c)/4(f) DE MINIMIS FINDING For the Provo Municipal Airport City of Provo, Utah County, Utah I. Introduction - Section 4(f) Section 4(f) was initially codified in Title 49 United States Code (USC) § 1653(f) (Section 4(f) of the USDOT Act of 1966). In 1983, § 1653(f) was reworded and recodified as Title 49 USC § 303 but is still commonly referred to as Section 4(f). Congress amended Section 4(f) in 2005 when the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) was enacted. Section 4(f) declares that “it is the policy of the US Government that special effort should be made to preserve the natural beauty of the countryside and public park and recreation lands, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and historic sites.” In addition: Section 4(f) prohibits the use of land of significant publicly owned public parks, recreation areas, wildlife and waterfowl refuges, and land of a historic site for transportation projects unless the Administration determines that there is no feasible and prudent avoidance alternative and that all possible planning to minimize harm has occurred. De minimis impacts related to historic sites are defined as the determination of either “no adverse effect” or “no historic properties affected” in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. For publicly owned parks, recreation areas, and wildlife/waterfowl refuges, de minimis impacts are defined as those that do not “adversely affect the activities, features, and attributes” of the Section 4(f) resource. -

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume I: Chapters 1–5

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume I: Chapters 1–5 April 2015 UTAH RECLAMATION 230 South 500 East, #230, Salt Lake City, UT 84102 COMMISSIONERS Phone: (801) 524-3146 – Fax: (801) 524-3148 Don A. Christiansen MITIGATION Brad T. Barber AND CONSERVATION Dallin W. Jensen COMMISSION Dear Reader, April 2015 Attached is the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Provo River Delta Restoration Project (PRDRP). The proposed project would restore a naturally functioning river- lake interface essential for recruitment of June sucker (Chasmistes liorus), an endangered fish species that exists naturally only in Utah Lake and its tributaries. In addition to fulfilling environmental commitments associated with water development projects in Utah and contributing to recovery of an endangered species, the project is intended to help improve water quality on the lower Provo River and to provide enhancements for public recreation in Utah County. Alternative B has been identified as the preferred alternative because it would minimize the amount of private lands that would need to be acquired for the project while still providing adequate space for a naturally functioning river delta and sufficient habitat enhancement for achieving the need for the project. The agencies preparing the Final EIS are the Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission (Mitigation Commission), the Central Utah Water Conservancy District, and the Central Utah Project Completion Act (CUPCA) Office of the U.S. Department of the Interior, collectively referred to as the Joint Lead Agencies. The Final EIS, Executive Summary and Technical Reports can be viewed or downloaded from the project website www.ProvoRiverDelta.us or by requesting a copy on CD. -

Economic Development Commission Launches

OUR TH YEAR www.slenterprise.com July 5, 2021 Volume , Number 50 $1.50 5O Economic development commission launches Weber & Davis commission will be “solutions-oriented.” tablishing subcommittees that serve as con- CountiesReal Estate Brice Wallace “I’m excited to work with state elect- veners to facilitate policy development. The Enterprise ed leaders, cabinet members, local officials “We’re thrilled to announce the cre- PAGE F1 pages 15-1 and others as we collaborate and create new ation of the new Unified Economic Oppor- A new commission charged with de- pathways to economic success,” Cox said. tunity Commission,” said Dan Hemmert, Sponsored by: veloping, directing and coordinating a The commission will convene stake- executive director of the Governor’s Of- statewide economic development strategy holders to develop solutions to the most fice of Economic Opportunity, or GO Utah. has begun its work. critical topics facing Utah’s economy. It That is the new name for the agency former- The Unified Economic Opportunity will also review and create new economic ly known as the Governor’s Office of Eco- Commission, created by HB348, passed strategies and programs to deal with time- nomic Development, or GOED. pages F1-F8 during the 2021 legislative session, has ly topics. Other purposes of the commis- “This commission will help with the been appointed and was scheduled to have sion include aligning economic efforts and state’s growth, education and workforce its first meeting last week, after The Enter- incentive programs, helping support and prise’s press deadlines. align education and industry partnerships Sponsored by: see COMMISSION page 14 Gov. -

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Bird-Aircraft Strike Risk Technical Memorandum Prepared for the Final Environmental Impact Statement

PROVO RIVER DELTA RESTORATION PROJECT Bird-Aircraft Strike Risk Technical Memorandum Prepared for the Final Environmental Impact Statement April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND RELEVANT BACKGROUND .................................................. 1 Description of Project Alternatives ............................................................................................. 6 2.0 METHODS .......................................................................................................................... 7 Describing Existing Bird Communities ...................................................................................... 7 Study Area Bird Surveys ........................................................................................................ 7 Internet and Other Data Sources ............................................................................................. 9 Assessment of Bird-Aircraft Strike Risk .................................................................................. 11 Quantitative Approach .......................................................................................................... 11 Habitat-Based Quasi-Quantitative Approach ....................................................................... 12 3.0 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................... 17 Existing Bird Communities based on Project Area Surveys, Provo’s Wildlife Hazard Assessment, and Bird Strike Reports ....................................................................................... -

The Films in This Cinematic Innovation, New Frontier Is Also a Venue Showcasing Section Will Shape a “Greater” Next Wave in American Cinema

T U , E C N A D N U S , T R O S E R N I A T N U O M E C N A D N U S F O Y S E T R U O C SUNDANCE INSTITUTE PRESENTS THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ABOUT SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ABOUT SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Sundance Institute is a nonprofit cultural organization Each January, the Sundance Film Festival attracts the most founded by Robert Redford to advance the work of risk-taking innovative storytellers and adventurous audiences to a 10-day storytellers worldwide. With a range of programs for artists celebration of the best independent filmmaking today. In a and audiences, the Institute provides year-round creative and small mountain town, a diverse range of ideas, stories, artists, financial support for the development and presentation of and film lovers converge to launch the year in culture. original stories for the screen and stage. W ELCOME ST RA NGER N Sundance Institute Presents E E R G R E 2014 Sundance Film Festival EV Here is an overview of the program at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. HA LF NE LSON U .S. DRAMATIC COMPETITION D OCUMENTARY PREMIERES FROM THE COLLECTION SUNDANCE KIDS Presenting the world premieres of 16 narrative feature films, Renowned filmmakers and films about far-reaching subjects Rediscover classic works of independent cinema as the This new section of the Festival is designed for independent the Dramatic Competition offers Festivalgoers a first look at comprise this section highlighting our ongoing commitment to Sundance Film Festival presents films from the vaults of the film’s youngest fans. -

Agenda Items Proposed for Action and Consideration (Pdf)

Utah Reclamation Mitigation & Conservation Commission COMMISSIONERS 230 South 500 East Suite 230 Salt Lake City, UT 84102-2045 Brad T. Barber, Chair Phone: (801) 524-3146 – Fax: (801) 524-3148 Robert L. Morgan Gene Shawcroft MEETING AGENDA Monday, September 13, 2021 TIME: 9:30 a.m. LOCATION: Utah Reclamation Mitigation and Conservation Commission, 230 S. 500 East Suite 230, Salt Lake City, UT, 84102 Also available online through Microsoft Teams Click here to join the meeting or type the following into your internet browser: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_MzAwN2ZmNzEtYzFmMS00Y2EwLTg5ODEtNjk5NTgzNjk1ZDI1%40th read.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%220693b5ba-4b18-4d7b-9341- f32f400a5494%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%2209fd8a27-76fc-460d-af33-294b0a20928f%22%7d ITEMS ON THE AGENDA FOR ‘ACTION’ AND FOR ‘CONSIDERATION’ MAY BE ACCESSED ON THE COMMISSION’S WEBSITE by navigating through mitigationcommission.gov/news Or at https://mitigationcommission.gov/news/pdf/AgreementsProposedForAction- Consideration.pdf 1. WELCOME AND OPENING REMARKS 2. APPROVAL OF PREVIOUS MINUTES 3. ITEMS FOR COMMISSION RATIFICATION A. A Resolution concurring in the issuance of the Final Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact for ‘Block Notice 7A-2 Temporary Use in North Utah County’ 4. ITEMS FOR COMMISSION ACTION A. Proposed Modification of Agreement with Provo City for Cooperative Planning, Design, Construction and Funding of the Provo Lakeview Parkway and Trail PRDRP B. Proposed Agreement with USDA-Wildlife Services for Funding Wildlife Hazard Mitigation at Provo Airport and Provo River Delta Restoration Project 5. ITEMS FOR COMMISSION CONSIDERATION None 6. PRESENTATIONS BY STAFF A. Diamond Fork System Update Draft Environmental Assessment B. -

Birds of the Brigham Young University Campus

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1956-06-01 Birds of the Brigham Young University campus Barid Baran Mukherjee Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Mukherjee, Barid Baran, "Birds of the Brigham Young University campus" (1956). Theses and Dissertations. 7832. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7832 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BIRDS 01'~ THE BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY CAMPUS A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Z,oology and Entomology Brigham Young University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of iV[ast.er of Science by Barid Baran Mukherjee June 1956 ACKNOV,·LEDGEMENTS The completion of this thesis, to a large extent, was possible because of the aid and assistance of several persons, and the writer here wishes to acknowledge very gratefully their contribution and expresses his deep appreciation to each one of them. The writer finds it difficult to express in words his sincere gratitude a-nd deep appreciation to Dr. C. Lynn Hayward, his Committee Chairman, who spent much of his precious time in helping and guiding this work, and without whose constant encouragement and assistance it would have been impossible for the writer to carry on and complete this study. Appreciation is especially extended to Dr. Lawrence Morris, the writer's committee member, who helped him immeasurably with con- stant encouragement. -

Feasibility Study for FBO/Aviation Service Provider Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) Salt Lake City, Utah

Feasibility Study for FBO/Aviation Service Provider **************** Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) Salt Lake City, Utah Prepared for: Mr. John Buckner, Jr. Director of Administration and Commercial Services Salt Lake City Department of Airports P.O. Box 145550 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114 Date of Report: December 31, 2013 Airport Business Solutions “Valuation and Consulting Services to the Aviation Industry” 13007 W. Linebaugh Avenue, #102 Suite B, Tampa, Florida 33626-4489 Phone (813) 855-3600 Fax (813) 200-1014 December 31, 2013 Mr. John Buckner, Jr. Director of Administration and Commercial Services Salt Lake City Department of Airports P.O. Box 145550 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114 RE: Feasibility Study for FBO/Aviation Service Provider Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) Salt Lake City, Utah Dear Mr. Buckner: Per the request by the Salt Lake City Department of Airports, we are pleased to present this document, which represents the Feasibility Study for an additional FBO/Aviation Service Provider at the Salt Lake City International Airport in Salt Lake City, Utah. The following report provides our assessment and analysis of various and potential issues related to the addition of another FBO/Aviation Service Provider, including the demand for such services and our recommendations for consideration. In the development of this document, Airport Business Solutions researched many sectors of the local, regional and national airport market, expanding as necessary to gain sufficient and comprehensive data to yield adequate and supportable conclusions. Moreover, we reviewed SLC operational and market data from a number of reliable sources, as well as data from the ABS proprietary industry database. -

Scoping Report

- Scoping Report - Old Spanish National Historic Trail Comprehensive Management Plan/ Environmental Impact Statement August 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management New Mexico State Office Division of Resources National Park Service National Trails System, Santa Fe Preparers: Sarah Schlanger Bureau of Land Management, New Mexico State Office Sharon Brown Aaron Mahr Otis Halfmoon National Park Service, National Trails System – Santa Fe TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms and Abbreviations……………………………………………………………..iii Introduction and Background ....................................................................................………..…...1 Issue Summary . ……………………………………………………………………..20 Draft Planning Criteria...............................................................................................……….…..30 Summary of Future Steps in the Planning Process………………………………………...…….32 TABLES Table 1. Paid Advertisements……………………………………………………………………6 Table 2. Public Scoping Meetings ……………………………………………………………....7 Table 3. Meeting Attendee Representation……………………………………………………...9 Table 4. Tribal Consultation Record …………………………….…………………………….15 MAPS Map 1. Designated trail………………………………………………………………………….3 APPENDICES Appendix 1. Media Releases………………………………………………...…………………34 Appendix 2. Written Comments Summary………………………………………………...…..40 Appendix 3. Verbal Comments Recorded During Public Meetings Summary………………..51 ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS BLM Bureau of Land Management NPS National Park Service USFS United States Forest Service, -

Enter the David Mccullough Visitscampus\\ ‘Kisstixx’ Hitsit Big\\ Also Inside \\ Pg

WINTER 2013 UTAH VALLEY UNIVERSITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE ALUMNI UNIVERSITY VALLEY UTAH ENTER THE ALSO INSIDE \\ DAVID MCCULLOUGH VISITS CAMPUS \\ PG. 8 ‘KISSTIXX’ HITS IT BIG \\ PG. 26 Liberty Mutual is a proud partner of Utah Valley University Alumni Association For additional information about Liberty Mutual and our car and home insurance, please contact us at 1-800-524-9400 or visit us at libertymutual.com/uvu. Smart Decisions for the New Year 1. Join UCCU Receive a FREE COSTCO MEMBERSHIP or RENEWAL* 2. Transfer Your Loans to UCCU Lower your rate | Lower your payment | Get 1% cash back up to $250** Call 801.223.8188 or visit any UCCU Branch today! *Costco Gift of Membership is a $55.00 cash card which can be used for: a 1-year Gold Star Membership to Costco Wholesale, an existing membership Renewal, or an Upgrade. For new members of UCCU to qualify to receive the Costco Gift of Membership $55.00 cash card they must open a checking account and setup direct deposit. For existing members of UCCU to qualify to receive the Costco Gift of Membership $55.00 cash card they can complete any one of the three options: (1) Open a UCCU checking account with a debit card and set up direct deposit. (2) Setup direct deposit AND transfer or obtain a loan with a balance of $1,000 or more. (3) Transfer or obtain a loan with a balance of $5,000 or more. Limited time o er. Cannot be combined with any other Utah Community Credit Union o er. -

Provo-Orem, Utah

COMPREHENSIVE HOUSING MARKET ANALYSIS Provo-Orem, Utah U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research As of June 1, 2017 Summary Economy 1,900 homes under construction and The Provo-Orem HMA added jobs at a portion of the estimated 3,200 other approximately triple the national rate vacant units that may reenter the market since the most recent national reces- will satisfy some of the forecast demand. Housing Market Area sion. During the 12 months ending May 2017, nonfarm payrolls averaged Rental Market 241,900, an increase of 10,800, or Rental housing market conditions in 4.7 percent, from a year earlier. The the HMA are currently balanced, with high-technology (hereafter, high-tech) Salt Lake Summit an overall estimated vacancy rate of Elko Wasatch Tooele industry benefits from the highly 4.0 percent, compared with 4.2 percent Nevada Utah Utah Duchesne educated workforce and two univer- in April 2010. Multifamily construction, Juab sities in the HMA, contributing to Carbon primarily of apartments, has nearly job growth. In addition, construction returned to the levels during the 2000s. White Pine White Millard Sanpete Emery payrolls and education and health During the forecast period, demand in The Provo-Orem Housing Market Area services are increasing to support the the HMA is expected for 4,175 new (HMA) is coterminous with the Provo- growing population. During the 3-year market-rate units. The approximately Orem, UT Metropolitan Statistical Area, forecast period, nonfarm payrolls are 1,500 units currently under construc- comprising Juab and Utah Counties in expected to increase by an average of tion will meet some of the forecast north central Utah, along the southern 9,100 jobs, or 3.8 percent, annually.