Concordia Theological Monthly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2016

ANGLICAN JOURNAL Since 1875 vol. 142 no. 10 december 2016 Welby, Francis vow to strive for social justice André Forget STAFF WRITER While decisions by some Anglican churches to ordain women and allow same-sex marriage have been major hindrances to formal unity between IMAGE: THOOM/SHUTTERSTOCK Anglicans and Roman Catholics, a common declaration issued by Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby and Pope Francis October 5 reaffirmed their commitment to ecumenical work. “While…we ourselves do not see solutions to the obstacles before us, we are undeterred,” the declaration says. “We are confident that dialogue and engagement with one another will deepen our understanding and help us to discern the See related story, mind of Christ for his church.” p. 3. See Anglicans, p. 13 ILLUSTRATION: ALIDA MASSARI IMAGE: SASKIA ROWLEY The task force on the theology of money argues that the current Rejoice economic system is an example of “structural sin.” There’s something special about Advent concerts, which draw Christians and non-Christians alike. See story p. 7 ‘A vision of enough’ André Forget Traumatized as a child, Rwandan Anglican STAFF WRITER On October 18, an Anglican Church of works to heal genocide-scarred youth Canada task force released “On the Theol- Tali Folkins about what the next day would bring, had ogy of Money,” a report calling the faithful STAFF WRITER to be reminded by their parents that it was to embrace a “vision of ‘enough’” when it Emmanuel Gatera was only five when time for bed. IMAGE: SKYBOYSV/SHUTTERSTOCK comes to material wealth. trauma of a kind so familiar to his fellow About an hour later, a mob of more Many Christians in the 21st century Rwandans first began to afflict his young than a hundred people had gathered are torn between their faith, which teaches brain. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

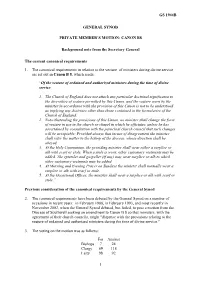

Gs 1944B General Synod Private Member's Motion

GS 1944B GENERAL SYNOD PRIVATE MEMBER’S MOTION: CANON B8 Background note from the Secretary General The current canonical requirements 1. The canonical requirements in relation to the vesture of ministers during divine service are set out in Canon B 8, which reads: “Of the vesture of ordained and authorized ministers during the time of divine service 1. The Church of England does not attach any particular doctrinal significance to the diversities of vesture permitted by this Canon, and the vesture worn by the minister in accordance with the provision of this Canon is not to be understood as implying any doctrines other than those contained in the formularies of the Church of England. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of this Canon, no minister shall change the form of vesture in use in the church or chapel in which he officiates, unless he has ascertained by consultation with the parochial church council that such changes will be acceptable: Provided always that incase of disagreement the minister shall refer the matter to the bishop of the diocese, whose direction shall be obeyed. 3. At the Holy Communion, the presiding minister shall wear either a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. When a stole is worn, other customary vestments may be added. The epistoler and gospeller (if any) may wear surplice or alb to which other customary vestments may be added. 4. At Morning and Evening Prayer on Sundays the minister shall normally wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole. 5. At the Occasional Offices, the minister shall wear a surplice or alb with scarf or stole.” Previous consideration of the canonical requirements by the General Synod 2. -

The Bugnini-Liturgy and the Reform of the Reform the Bugnini-Liturgy and the Reform of the Reform

in cooperation with the Church Music Association of America MusicaSacra.com MVSICAE • SACRAE • MELETEMATA edited on behalf of the Church Music Association of America by Catholic Church Music Associates Volume 5 THE BUGNINI-LITURGY AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM THE BUGNINI-LITURGY AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM by LASZLO DOBSZAY Front Royal VA 2003 EMINENTISSIMO VIRO PATRI VENERABILI ET MAGISTRO JOSEPHO S. R. E. CARDINALI RATZINGER HOC OPUSCULUM MAXIMAE AESTIMATIONIS AC REVERENTIAE SIGNUM D.D. AUCTOR Copyright © 2003 by Dobszay Laszlo Printed in Hungary All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Conventions. No part of these texts or translations may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher, except for brief passages included in a review appearing in a magazine or newspaper. The author kindly requests that persons or periodicals publishing a review on his book send a copy or the bibliographical data to the following address: Laszlo Dobszay, 11-1014 Budapest, Tancsics M. u. 7. Hungary. K-mail: [email protected] Contents INTRODUCTION Page 9 1. HYMNS OF THE HOURS Page 14 2. THE HOLY WEEK Page 20 3. THE DIVINE OFFICE Page 45 4. THE CHANTS OF THE PROPRIUM MISSAE VERSUS "ALIUS CANTUS APTUS" Page 85 5. THE READINGS OF THE MASS AND THE CALENDAR Page 121 6. THE TRIDENTINE MOVEMENT AND THE REFORM OF THE REFORM Page 147 7. HIGH CHURCH - LOW CHURCH: THE SPLIT OF CATHOLIC CHURCH MUSIC Page 180 8. CHURCH MUSIC AT THE CROSSROADS Page 194 A WORD TO THE READER Page 216 Introduction The growing displeasure with the "new liturgy" introduced after (and not by) the Second Vatican Council is characterized by two ideas. -

Building on a Rickety Foundation: “An Evangelical Agenda”

BUILDING ON A RICKETY FOUNDATION: “AN EVANGELICAL AGENDA” James McPherson During one of the meal adjournments from Synod 2001, the Revd Phillip Jensen addressed the Anglican Church League. It was a “missionary” address, titled “An Evangelical Agenda”.1 He promoted “church-planting” and outlined a putative justification for his proposed strategy. His address was notable for its sweeping generalisations and innuendo, eg about “revisionism” and the alleged evils of Tractarianism. Putting to one side all matters of rhetorical technique, the logic of Mr Jensen’s address was that • “the parish system” was working well; • until the Tractarians damaged the parish system irreparably; • so the remedy is to bypass existing parishes damaged by Tractarian and other revisions, and restore authentic Anglicanism. He went further, concluding his address by urging ACL members to campaign so that the churches planted by those who have been forced outside the denomination (ie, by collateral damage to its theology and institutional structures) should be embraced as part of the Anglican family. It is clear from his address that he is promoting competitive rather than collaborative church- planting. That is, this church-planting is not undertaken with the full knowledge and willing cooperation of an existing Anglican parish, but because the existing parish is judged to be defective and thus for the cause of the gospel should be challenged, exposed, and perhaps even extinguished. I intend to show first that Mr Jensen’s proposal bristles with practical difficulties; and second, that it is based on a theologically prejudiced reading of history. Such a view of the past does not commend those who hold it as reliable guides for the future. -

Universitv of }Ianitoba

ENGLISH PROTESTANT NEACTIONS TO THE COUNCIL OF TRENT A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Graduate Studies Universitv of }ianitoba In Partial Fulfill-ment of the Recluirements for the Der"ree l'laster of Arts by Ben Ilarder r973 TNGLISH PROTESTANT REACTIONS TO THE COUNCIL OF TRENT by BEN HARDTR A dissert¡.rtion subnlittcd to tltc [ìlculty of'Graduutc Sttrclics of' tllc Univcrsity ol' Ivl:rnitobr in ¡-xrrti;rl l'ull'illmcnt of' the roqLtirotncltts tll' thc dcgt'cc rll' MASTER OF ARTS @ t9l4 l)cnnissit¡n h¿ts lrcclt gl';.trttcrl to thc l.llìllAlìY Ol;'l'llti LlNlVlill- Sl'l'Y Otj l\,1^Nl'l'OllA to lc¡rtl or scll copics ol'this tlisscrtrttiotl, ttr Lhc NAT'tONAL Lltsl{^llY Ot'('^N^l)^ to ¡tricrol'ilrn tllis disscrtatioll ¿utd to lenü or scrll cqpics rrl'tltc l'illll, lrld LJNlVlillSl't\' MICIì()t ILMS to publish rtrl ¿tlr.strrtr;t of'this tlisscrfirtioll. 'l'hs autltor roscrves othcr ¡rtrblictttititt rights, lrttl tlcitltcl' thc disscrtatio¡¡ ¡lor exteltsivc cxtracts l'¡r¡tt't it nray bc printcd or tttltcr- wise rcprtrtluccd without t llc atltl¡tlt'"s wl'it tc¡t ¡rct'ttt is;siotl- TABLE O]T COT,IT]J}iTS IIJTROIIUCTION o o o ø o o o é ø è o o o o o o o o I J. THE COUI'rCII, Il'l iii'iGl.ISH PJRSP]ìCTIVE o ô ê o 12 The Character of the Engli-sh Refornati-on England ts EarJiest Protestants Fienry UJII and the Conciliar Question Henrician Propaganda Cranmer ancÌ the Pan-Protestant Confess ion II. -

Ttbe ©Rnaments 1Rubric. the BISHOP of MANCHESTER and the E.C.U

THE ORNAMENTS RUBRIC ttbe ©rnaments 1Rubric. THE BISHOP OF MANCHESTER AND THE E.C.U. BY THE REV. c. SYDNEY CARTER, M.A., Chaplain of St. Mary Magdalen, Bath. E suppose that the Bishop of Manchester is to be com W plimented on having been considered a sufficiently com petent authority to engage the attention of the legal committee of the English Church Union. Their Council have issued a "Criticism. and Reply" 1 to his lordship's recent "Open Letter" to the Primate, in which he seriously challenged the exparte con clusions contained in the " Report of the Five Bishops " of Canterbury Convocation on the Ornaments Rubric. This curiously worded pamphlet certainly reflects far more credit on the ingenuity and casuistry than on the ability and accurate knowledge of the legal committee of the E.C. U. It abounds in unwarrantable assumptions, glaring inaccuracies, flagrant misrepresentations, and careful suppression of facts ; and the Bishop of Manchester is certainly to be congratulated if his weighty contention encounters no more serious or damaging opposition than is afforded in these twenty-four pages. One or two examples will sufficiently illustrate the style of argument employed throughout. The natural conclusion stated in the '' Report," that the omission in prayers and rubrics of a cere mony or ornament previously used was '' the general method employed" by the compilers of the Prayer-Books for its aboli tion or prohibition, is contemptuously dismissed in this pamphlet as an " untenable theory." Thus, not only are we told that the Ornaments Rubric was definitely framed as "the controlling guide" of what ornaments were to be retained and used and as "a guide for the interpretation of other rubrics," but that it is also "a directory to supply omissions as to ceremonies which 1 " The Ornaments Rubric and the Bishop of Manchester's Letter : A Criticism and .a Reply." Published by direction of the Council of the English Church Union. -

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Andrew Bielak, In Residence noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant Monday: Miraculous Medal Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Vespers and Benediction: Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. -

Discipleship in the Lectionary – 06/27/2021

Discipleship in the Lectionary – 06/27/2021 A look at the week's lectionary through the lens of discipleship and disciple- making. Fifth Sunday After Pentecost Revised Common Lectionary Year B Sunday, June 27th Mark 5:21-43 Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Transformed through faith This week’s Gospel lection contains two healing stories, one intercalated within the other: The raising of Jairus’ daughter from the dead and the healing of a woman with a hemorrhage. If we take these intricately interwoven stories as an isolated text, our focus is drawn primarily to the healings. When we take the broader literary context of Mark’s Gospel into account, another focal point emerges. There is a contrast here between the lack of faith of Jesus’ disciples covered in last week’s Gospel lection (Mark 4:35-41) and the faith of the woman and Jairus in this week’s text. Mark’s manual on discipleship thus uses more than just the text to emphasize the importance of faith – even in situations of complete hopelessness. At the same time, Jesus does not just restore those afflicted but transforms them. Faith in Christ has social costs, but such faith is necessary to transform society’s ills. Mark 5:21-43 Commentary In last week’s Gospel lection, Jesus and His disciples encountered a violent storm while crossing over the Sea of Galilee. Once they arrived on the Gentile shore, Jesus exorcised the Gerasenes demoniac and then headed back to the Jewish side of the lake. -

Book of Common Prayer

The History of the Book of Common Prayer BY THE REV. J. H. MAUDE, M.A. FORMERLY FELLOW AND DEAN OF HERTFORD COLLEGE, OXFORD TENTH IMPRESSION SIXTH EDITION RIVINGTONS 34 KING STREET, COVENT GARDEN LONDON 1938 Printed in Great Britain by T. AND A.. CoNSTABLE L'PD. at the University Press, Edinburgh CONTENTS ORAl'. I. The Book of Common Prayer, 1 11. The Liturgy, 16 In•• The Daily Office, 62 rv. The Occasional Offices~ 81 v. The Ordinal, 111 VI. The Scottish Liturgy, • 121 ADDITIONAL NoTES Note A. Extracts from Pliny and Justin Ma.rtyr•• 1.26 B. The Sarum Canon of the Mass, m C. The Doctrine of the Eucharist, 129 D. Books recommended for further Study, • 131 INDBX, 133 THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER CHAPTER I THE BOOK OF COl\IMON PRAYER The Book of Common Prayer.-To English churchmen of the present day it appears a most natural arrangement that all the public services of the Church should be included in a single book. The addition of a Bible supplies them with everything that forms part of the authorised worship, and the only unauthorised supple ment in general use, a hymn book, is often bound up with the other two within the compass of a tiny volume. It was, however, only the invention of printing that rendered such compression possible, and this is the only branch of the Church that has effected it. In the Churches of the West during the Middle Ages, a great number of separate books were in use; but before the first English Prayer Book was put out in 1549, a process of combination had reduced the most necessary books to five, viz. -

Paul in Acts and Paul in His Letters

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) 310 Daniel Marguerat Paul in Acts and Paul in His Letters Mohr Siebeck Daniel Marguerat, born 1943; 1981 Habilitation; since 1984 Ordinary Professor of New Testa- ment, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Lausanne; 2007–2008 President of the “Studiorum Novi Testamenti Societas”; since 2008 Professor Emeritus. ISBN 978-3-16-151962-8 / eISBN 978-3-16-157493-1 unveränderte eBook-Ausgabe 2019 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum NeuenT estament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http: / /dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer inT übingen, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface This book is a collection of 13 essays devoted to Paul, however they follow the path of reverse chronology: starting with the reception of Paul and moving back to the apostle’s writings. The reason for this is revealed in the first chapter which acts as the program of this book: “Paul after Paul: a (Hi)story of Reception”. -

The Oxford Movement in the Southern Presbyterian Church

THE UNION SEMINARY MAGAZINE , NO. 3–JAN.-FEB., 1897. \ i t I.—LITERARY. THE OXFORD MOVEMENT IN THE SOUTHERN PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH. The Oxford Movement in the Church of England began about 1833. It was a reaction against liberalism in politics, latitudinarianism in theology, and the government of the Church by the State. It was, at the same time, a return to Mediaeval theology and worship. The doctrines of Apostoli cal Succession, and the Real Presence—a doctrine not to be distinguished from the Roman Catholic doctrine of transub stantiation—were revived. And along with this return to Mediaeval theology, Mediaeval architecture was restored; temples for a stately service were prepared; not teaching halls. Communion tables were replaced by altar's. And the whole paraphernalia of worship was changed ; so that, except for the English tongue and the mustaches of the priests, the visitor could hardly have told whether the worship were that of the English Church or that of her who sitteth on “the seven hills.” It must be admitted that there was some good in the move ment. The Erastian theory as to the proper relation of Church and State is wrong. The kingdom of God should not be sub ordinate to any “world-power.” No state should control the Church. And certainly such latitudinarianism in doctrine as that of Bishop Coleuso and others called for a protest. But the return to Mediaeval theology and Mediaeval worship was all wrong. We have no good ground for doubting the sincerity of many of the apostles of the movement. Unfortunately, more than 146 THE UNION SEMINARY MAGAZINE.