Journal of Ukrainian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord Weekly (November 19, 1992)

THE CORD A WILFRID LAURIER UNIVERSITY STUDENT PUBLICATION VOLUME XXXIII ISSUE 14 NOVEMBER 19 1992 Second Cup gets Champions. the support of over 3000 staff and students few weeks. The current total of Lianne Jewitt by has signatures on both petitions The Second Cup, favoured reached over 3000. and among students, faculty, When asked to comment on staff alike is scheduled to be re- the petitions, Rayner said that he as of December 11, 1992; placed "hasn't seen the petitions." Rayner a petition is being circulated in also said that "we'll consider the or them response to this aspects action. (the petitions)". Director of Exactly what Personnel and The current number will be consider- Administrative ed is uncertain, as Services, Earl Rayner clearly of on signatures states Rayner, said the that the Second reason for re- Cup was of the given a "one placement both petitions has year Second Cup is trial basis", and that it is "costing the decision for their dismissal us too much reached over 3000. "made money to havfc it was this there." Rayner past September." The Lady Soccer Hanks wwn—i the iliwnto, McMaater, St. Mary's, and McQIII, added, "the return It was the Second title. and return to Laurlor aHh the National Cluaipto—tUp - ■ I D<lfc gTOarGO If®** VVGRMfI to the university is hardly cover- Cup's one year anniversary on ing our costs." campus. Rayner has not mentioned WLU student confesses Quite clearly, coffee and hot what will be the replacing popu- chocolate drinkers, and cookie lar coffee cart, but concerned coffee drinkers fear it to in bomb threat campus and muffin eaters' main concern calling will be a university-run establish- with the pending absence of the ment Second Cup is the lack of quality "I think it's terrorism, and certainly deserving of Dean of Student's Pat Brethour secretary, that awaits if a university run ser- by charges," said Fred Nichols, Dean of Students. -

A C C E P T E

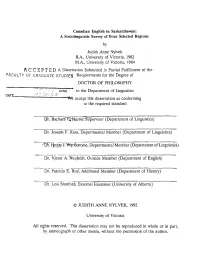

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

Conflicting Responsibilities: the Multi-Dimensional Ethics of University/Community Partnerships Page 8

Vol. 11, No. 2, 2019 Conflicting Responsibilities: The Multi-Dimensional Ethics of University/Community Partnerships Page 8 Power and Negotiation in a Asset Mapping and Focus Group Usage: University/Community Partnership An Exploration of the Russian-Ukrainian Serving Jewish Teen Girls Page 19 Population’s Need For and Use of Health-Related Community Resources Civic Capacity and Engagement Page 43 in Building Welcoming and Inclusive Communities for Newcomers: Community-Based Participatory Praxis, Recommendations, and Research and Sustainability: Policy Implications Page 31 The Petersburg Wellness Consortium Page 54 JCES11.2 Cover&Spine.indd 1 5/29/19 10:39 AM Save the Date Engagement Scholarship Consortium International Conference Pre-conference: September 13–14, 2020 Main conference: September 15–16, 2020 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Eastern Region Hosts: 19-CI-0029/san/sss JCES11.2 Cover&Spine.indd 2 5/29/19 10:39 AM Copyright © 2019 by The University of Alabama Division of Community Affairs. All rights reserved. ISSN 1944-1207. Printed by University Printing at The University of Alabama. JCES11.2InsidePages.indd 1 5/31/19 10:33 AM Publisher Associate Editor, Production Editor/ Samory T. Pruitt, PhD Student and Community Web Producer Vice President, Division of Engagement Karyn Bowen Community Affairs Katherine Richardson Bruna, PhD Marketing Manager The University of Alabama Professor, School of Education Division of Community Affairs Iowa State University The University of Alabama Editor Marybeth Lima, PhD Editorial Assistant Assistant to the Editor Cliff and Nancy Spanier Edward Mullins, PhD Krystal Dozier, Doctoral Student Alumni Professor Director, Communication and School of Social Work Louisiana State University Research, Center for Community- The University of Alabama Based Partnerships Associate Editor The University of Alabama Student Associate Editor Andrew J. -

The CJFL TOTAL THURSDAY Newsletter

www.cjfl.net “For all your CJFL Information & News” The CJFL TOTAL THURSDAY Newsletter Brought to you by Issue 3 – Volume 1 "The CJFL gratefully acknowledges the support of the following Sponsors" "The Canadian Junior Football League provides the opportunity for young men aged 17 to 22 to participate in highly competitive post-high school football that is unique in Canada. The goal of the league is to foster community involvement and yield a positive environment by teaching discipline, perseverance and cooperation. The benefits of the league are strong camaraderie, national competition and life-long friends." History of True Sport In 2001, Canada’s Federal-Provincial/Territorial Ministers responsible for sport came together to bring ethics and respectful conduct back into the way Canadians play and compete. They believed that damaging practices—cheating, bullying, violence, aggressive parental behaviour, and even doping—were beginning to undermine the positive impact of community sport in Canada. The first step they took in turning back this negative tide was the signing of what is now known as the London Declaration, an unprecedented affirmation of positive sporting values and principles. The Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport conducted a nationwide survey in 2002, which made clear the important role that sport plays in the lives of Canadians, as well as Canadians’ strong desire to uphold a model of sport that reflects and teaches positive values like fairness, inclusion, and excellence. In September of 2003, leading sports officials, sports champions, parents and kids from across Canada came together through a symposium entitled “The Sport We Want.” Several strong messages emerged from this gathering. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

Corporate Pin Club Members – Pins for Sale

Corporate WPCC Pin Club Members – Member Specials Canadian Football Hall of Fame & Museum 15% discount on assorted CFL Team pins & Grey Cup pins. To order, please visit the website at: http://www.cfhof.ca/ When ordering pins online, please type in the promo code # WPC. Free shipping on orders of 10 pins or more. If you are travelling to Hamilton, visit the Canadian Football’s Hall of Fame & Museum store at 58 Jackson Street West, Hamilton, Ontario. Friends of the Canadian Human Rights Museum Star shaped “Shine” pins for sale at $5.00 each. The pins remind us to Reach for the stars and strive for excellence. To order visit the website at: http://www.foreverchanged.ca/index.cfm?pageID=40 or visit any of the following Winnipeg retailers that sell their "Shine" pins: - Grant Park and Portage Place - 3 Locations in Winnipeg - 107 - 1 Forks Market - James Richardson Airport - 2000 Wellington Ave Laurie Artiss Since 1976, Laurie Artiss has been a producer of high quality pins for the Olympics, world curling, sports teams, the Winnipeg Pin Collectors Club, corporations, organizations etc. Club members ordering pins will receive a 10% discount and are eligible for a further 5% discount if they prepay. For more information, visit their website at: http://www.thepinpeople.ca/ Winnipeg Jets 10% discount on Winnipeg Jets pins. To order, visit their website at: http://jets.nhl.com/ or visit the Winnipeg Jets' "Jets Gear" store at the MTS Centre, 300 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg or the new “Jets Gear” store located in the St. Vital Shopping Centre, Winnipeg. -

I – Les Relations Extérieures Du Canada »

Article « I – Les relations extérieures du Canada » Hélène Galarneau et Manon Tessier Études internationales, vol. 21, n° 3, 1990, p. 565-588. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/702704ar DOI: 10.7202/702704ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 13 février 2017 10:33 Chronique des relations extérieures du Canada et du Québec Hélène GALARNEAU et Manon TESSIER* I - Les relations extérieures du Canada (avril à juin 1990) A — Aperçu général Ce trimestre de printemps était encore l'occasion de nombreuses réunions internationales que ce soit celles, récurrentes, du FMI, de la Banque mondiale et de l'OTAN ou celles, ponctuelles, tenues dans le cadre de la Conférence sur la sécurité et la coopération en Europe. Si un trait commun unissait ces rencontres multilatérales, c'est bien celui de l'adaptation aux nouvelles réalités européen nes et de ses répercussions sur les alliances militaires ou sur l'économie inter nationale. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

Oleh Gerus Fonds (MSS 367)

University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections Finding Aid - Oleh Gerus fonds (MSS 367) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: May 11, 2020 Language of description: English University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections 330 Elizabeth Dafoe Library Winnipeg Manitoba Canada R3T 2N2 Telephone: 204-474-9986 Fax: 204-474-7913 Email: [email protected] http://umanitoba.ca/libraries/archives/ http://umlarchives.lib.umanitoba.ca/index.php/oleh-gerus-fonds Oleh Gerus fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - MSS 367 Oleh Gerus fonds Summary information Repository: University of Manitoba -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1993, No.23

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • Ukraine's search for security by Dr. Roman Solchanyk — page 2. • Chornobyl victim needs bone marrow transplant ~ page 4 • Teaching English in Ukraine program is under way - page 1 1 Publishfd by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-prof it association rainianWee Vol. LXI No. 23 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JUNE 6, 1993 50 cents New York commemorates Tensions mount over Black Sea Fleet by Marta Kolomayets Sea Fleet until 1995. 60th anniversary of Famine Kyyiv Press Bureau More than half the fleet — 203 ships — has raised the ensign of St. Andrew, by Andrij Wynnyckyj inaccurate reports carried in the press," KYYIV — Ukrainian President the flag of the Russian Imperial Navy. ranging from those of New York Times Leonid Kravchuk has asked for a summit NEW YORK — On June 1, the New None of the fleet's Warships, however, reporter Walter Duranty written in the meeting with Russian leader Boris have raised the ensign. On Friday, May York area's Ukrainian Americans com 1930s, to recent Soviet denials and Yeltsin to try to resolve mounting ten memorated the 60th anniversary of the Western attempts to smear famine sions surrounding control of the Black (Continued on page 13) tragic Soviet-induced famine of І932- researchers. Sea Fleet. 1933 with a "Day of Remembrance," "Now the facts are on the table," Mr. In response, Russian Foreign Minister consisting of an afternoon symposium Oilman said. "The archives have been Andrei Kozyrev is scheduled to arrive in Parliament begins held at the Ukrainian Institute of opened in Moscow and in Kyyiv, and the Ukraine on Friday morning, June 4, to America, and an evening requiem for the Ukrainian Holocaust has been revealed arrange the meeting between the two debate on START victims held at St. -

Le Tabac Ne Rapporte Pas Plus

Ut Inàuttnt» Toibt lm Ntdf REVETEMENT km Dodge 4k TOLE EMAILLEE IMS 11 UIRtSLKKÜf **• Mm UMfTI AMM MMCfUTd 822-2424 me: Tel.: (418)872-3738 cw chez ■mMMM 1 7i0. route de l'Aéroport. Somle-7oy J JL! ta citant cfcexxao SOLEIL C P 70, l'Anc*e»»ne-Lo»ette G2I 3M2 QUEBEC 9TE ANNEE NO?* 23 JANVIER 1993 PH*TPS SAMEDI LIVRAISON A DOMICILE [7 JOURS, 3.50 TPS 024 100 PAGES 7 CAHIERS ♦ 1 TA8LOO T VQ 090 4.04 MONTREAL OTTAAA 1.50 ^{Jq 1,35$ T V Q LE SPORT Malgré des hausses de taxes de 118% en cinq ans Le tabac ne rapporte pas plus Les Nordiques tenteront de se reprendre au Colisée QUÉBEC — En cinq ans, soit de 1988 à 1992-93, les taxes Selon des chiffres fournis cigarettes vendues démontré Devant cette situation, les sur un paquet de 25 cigarettes ont augmenté au Québec de Indisciplinés, les Nordiques ont été par le sous-ministre adjoint aux donc clairement qu’une propor pressions, particulièrement de 118 %, faisant passer le prix du paquet de 3,35 $ à (>.15 $. Finances Marcel Leblanc, la déclassés surtout au chapitre de la rapidité tion importante de la consom l'industrie du tabac, sont nom hausse de 118 % des taxes entre d exécution et de la robustesse, a Buffalo, Au cours de la même période, l'assiette fiscale des produits du mation échappé aujourd'hui breuses sur le gouvernement 1988-89 et 1992-93 se lit comme aux taxes, proportion que M. quebecoispour qu’il abaisse et les Sabres font emporte 6-2 S-2 et S-3 tabac du gouvernement du Québec, soit le volume total de cigarettes vendues, était en baisse de 45 %. -

Peter Anastas Papers

PETER ANASTAS PAPERS Creator: Peter Nicholas Anastas Dates: 1954-2017 Quantity: 26.0 linear feet (26 document boxes) Acquisition: Accession #: 2014.077 ; Donated by: Peter Anastas Identification: A77 ; Archive Collection #77 Citation: [Document Title]. The Peter Anastas Papers, [Box #, Folder #, Item #], Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Peter Anastas Biographical Note Peter Nicholas Anastas, Jr. was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1937. He attended local schools, graduating in 1955 from Gloucester High School, where he edited the school newspaper and was president of the National Honor Society. His father Panos Anastas, a restaurateur, was born in Sparta, Greece in 1899, and his mother, Catherine Polisson, was born in Gloucester of native Greek parents, in 1910. His brother, Thomas Jon “Tom” Anastas, a jazz musician, arranger and composer, was born in Gloucester, in 1939, and died in Boston, in 1977. Anastas attended Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, on scholarship, majoring in English and minoring in Italian, philosophy and classics. While at Bowdoin, he wrote for the student Peter Anastas Papers – A77 – page 2 newspaper, the Bowdoin Orient, and was editor of the college literary magazine, the Quill. In 1958, he was named Bertram Louis, Jr. Prize Scholar in English Literature, and in 1959 he was awarded first and second prizes in the Brown Extemporaneous Essay Contest and selected as a commencement speaker (his address was on “The Artist in the Modern World.”) During his summers in college, Anastas edited the Cape Ann Summer Sun, published by the Gloucester Daily Times, and worked on the waterfront in Gloucester.