The Origins of Self-Consciousness in the Secret Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2010 the Volume 6 Esoteric Number 3

Fall 2010 The Volume 6 Esoteric Number 3 A publication of the School for Esoteric Quarterly Studies Esoteric philosophy and its applications to individual and group service and the expansion of human consciousness. The School for Esoteric Studies. 345 S. French Broad Avenue, Suite 300. Asheville, North Carolina 28801, USA. www.esotericstudies.net/quarterly; e-mail: [email protected]. The Esoteric Quarterly The Esoteric Quarterly is published by the School for Esoteric Studies. It is registered as an online journal with the National Serials Data Program of the Library of Congress. International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) 1551-3874. Further information about The Esoteric Quarterly, including guidelines for the submission of articles and review procedures, can be found at: www.esotericstudies.net/quarterly. All corres- pondence should be addressed to [email protected]. Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief: Donna M. Brown (United States) Review Editor: Joann S. Bakula (United States) Editor Emeritus: John F. Nash (United States) Alison Deadman (Tennessee) Judy Jacka (Australia) Katherine O'Brien (New Zealand) Gail G. Jolley (United States) Barbara Maré (New Zealand) Webmaster: Dorothy I. Riddle (Canada) Copyright © The Esoteric Quarterly, 2010 All rights reserved. Copies of the complete journal or articles contained therein may be made for personal use on condition that copyright statements are included. Commercial use without the permission of The Esoteric Quarterly and the School for Esoteric Studies is strictly prohibited. Fall 2010 The Esoteric Quarterly Contents Volume 6, Number 3. Fall 2010 Page Page Consciousness, Cognitive 37 Features Neuroscience and Divine Editorial 5 Embodiment: Suggestions for Group Work Publication Policies 6 Jon Darrall-Rew Letters to the Editor 7 Methods of Service for the 53 Poem of the Quarter: “ The 8 Seven Rays Comet - With Tears and Zachary F. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

THE SERMON on the MOUNT According to VEDANTA Other MENTOR Titles of Related Interest

\" < 'y \ A MENTOR BOOK 1 ,wami \ « r a m A |a fascinating Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Public.Resource.Org https://archive.org/details/sermononmountaccOOprab 66Like Krishna and Buddha, Christ did not preach a mere ethical or social gos¬ pel hut an uncompromisingly spiritual one. He declared that God can be seen, that divine perfection can be achieved. In order that men might attain this su¬ preme goal of existence, he taught the renunciation of worldliness, the con¬ templation of God, and the purification of the heart through the love of God. These simple and profound truths, stated repeatedly in the Sermon on the Mount, constitute its underlying theme9 as I shall try to show in the pages to followr —from the Introduction by Swami Prabhavananda THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT according to VEDANTA Other MENTOR Titles of Related Interest □ SHAN KARA'S CREST-JEWEL OF DISCRIMINA¬ TION translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Ssherwood. The philosophy of the great Indian philosopher and saint, Shankara. Its implications for the man of today are sought out in the Introduction, (#MY1054—$1.25) □ THE SONG OF GOD: RHAGAVAD-GITA translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isher- wood. A distinguished translation of the Gospel of Hinduism, one of the great religious classics of the world. Introduction by Aldous Huxley. Appen¬ dices. (#MY1425—$1.25) □ THE UPAN5SHAD8: BREATH OF THE ETERNAL translated by Swam! Prabhavananda and Freder¬ ick Manchester. Here is the wisdom of the Hindu mystics in principal texts selected and translated from the original Sanskrit. (#MY1424—$1.25) □ HOW TO KNOW GOD: THE YOGA APHORISMS OF PATANJALI translated with Commentary by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isher- wood. -

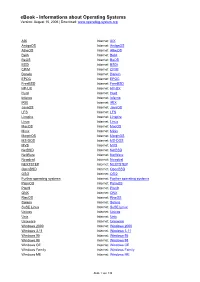

Ebook - Informations About Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download

eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org AIX Internet: AIX AmigaOS Internet: AmigaOS AtheOS Internet: AtheOS BeIA Internet: BeIA BeOS Internet: BeOS BSDi Internet: BSDi CP/M Internet: CP/M Darwin Internet: Darwin EPOC Internet: EPOC FreeBSD Internet: FreeBSD HP-UX Internet: HP-UX Hurd Internet: Hurd Inferno Internet: Inferno IRIX Internet: IRIX JavaOS Internet: JavaOS LFS Internet: LFS Linspire Internet: Linspire Linux Internet: Linux MacOS Internet: MacOS Minix Internet: Minix MorphOS Internet: MorphOS MS-DOS Internet: MS-DOS MVS Internet: MVS NetBSD Internet: NetBSD NetWare Internet: NetWare Newdeal Internet: Newdeal NEXTSTEP Internet: NEXTSTEP OpenBSD Internet: OpenBSD OS/2 Internet: OS/2 Further operating systems Internet: Further operating systems PalmOS Internet: PalmOS Plan9 Internet: Plan9 QNX Internet: QNX RiscOS Internet: RiscOS Solaris Internet: Solaris SuSE Linux Internet: SuSE Linux Unicos Internet: Unicos Unix Internet: Unix Unixware Internet: Unixware Windows 2000 Internet: Windows 2000 Windows 3.11 Internet: Windows 3.11 Windows 95 Internet: Windows 95 Windows 98 Internet: Windows 98 Windows CE Internet: Windows CE Windows Family Internet: Windows Family Windows ME Internet: Windows ME Seite 1 von 138 eBook - Informations about Operating Systems Version: August 15, 2006 | Download: www.operating-system.org Windows NT 3.1 Internet: Windows NT 3.1 Windows NT 4.0 Internet: Windows NT 4.0 Windows Server 2003 Internet: Windows Server 2003 Windows Vista Internet: Windows Vista Windows XP Internet: Windows XP Apple - Company Internet: Apple - Company AT&T - Company Internet: AT&T - Company Be Inc. - Company Internet: Be Inc. - Company BSD Family Internet: BSD Family Cray Inc. -

Lettera Dell'alfabeto Turco, La Quale Si Usa Anche Con Gli Accenti Aggiuntivi Per Comporre Ì, Í, Ï

I ı senza punto [ ı ]. Lettera dell’alfabeto turco, la quale si usa anche con gli accenti aggiuntivi per comporre ì, í, ï, ĩ. i.e. → id est ialografia [dal gr. hýalos, «vetro», e grafia, dal gr. -graphía, der. di gráphō, «scrivere»]. Incisione su vetro. Si può anche impiegare come fototipo* per ottenere una forma di stampa. ialotipia [dal gr. hýalos, «vetro», e tipia, da tipo- dal lat. typus, gr. týpos, «impronta, carattere»]. Procedimento di stampa che utilizza lastre di zinco su cui sono riportate incisioni fatte su lastre di vetro. iato [dal lat. hiatus -us, der. di hiare, «aprirsi»]. Indica l’incontro di vocali non solo nel corpo d’una stessa parola, ma anche in fine e principio di due parole consecutive. (v. anche elisione). ib., ibid. → ibidem ibidem [it. in quello stesso luogo]. Termine latino, spesso abbreviato ib., che significa nello stesso luogo. Utilizzato nelle note a piè di pagina, consente di evitare di ripetere il titolo dell’opera citata subito prima. IBN → Index bio-bibliographicus notorum hominum (IBN). ibrida [ingl. hibrid; dal lat. hybrĭda «bastardo», di etimo incerto]. Termine utilizzato per definire una scrittura che mostra elementi di scritture diverse. ICA Acronimo di International Council of Archive (<www.ica.org>). icnografia [dal gr. ichnographía, comp. di íchnos, «traccia» e -graphía «-grafia»]. Rappresentazione grafica, in proiezione ortogonale, della sezione orizzontale di un edificio. Sinonimo di pianta. icòna [dal gr. biz. eikóna, gr. class. eikṓn -ónos, «immagine»]. 1. Immagine sacra, rappresentante il Cristo, la Vergine, uno o più santi, dipinta su tavoletta di legno o lastra di metallo, spesso decorata d’oro, argento e pietre preziose, tipica dell’arte bizantina e, in seguito, di quella russa e balcanica. -

The Upper Triad Material Cosmic Fire

The Upper Triad Material Topical Issue 7.71 Cosmic Fire The Key to Manifestation ____________________________________________________________ The Upper Triad Material Topical Issue 7.71 Cosmic Fire ____________________________________________________________ Fourth Edition, September 2006 ____________________________________________________________ Published by The Upper Triad Association P.O. Box 1306 Victoria, Virginia 23974 ( USA ) The Upper Triad Association is a 501 ( c ) 3 non-profit educational organization established in 1974 and devoted to the study and practice of various principles leading to personal and spiritual growth. www.uppertriad.org ____________________________________________________________ ii Contents Page ● Chapter 7.71 Cosmic Fire 1 ● Section 7.711 The Triple Fire 2 Cosmic Fire 1 C 569 3 Cosmic Fire 2 C 570 4 Fire by Friction C 573 6 Solar Fire C 574 8 Electric Fire C 575 9 Cosmic Fire 6 C 577 11 ● Section 7.712 The Internal Fires 13 Cosmic Fire 7 C 583 14 Cosmic Fire 8 C 584 15 The Etheric Body and Prana 1 C 588 17 The Etheric Body and Prana 2 C 592 19 The Etheric Body and Prana 3 C 596 20 The Etheric Body and Prana 4 C 600 22 The Etheric Body and Prana 5 C 604 24 Kundalini and the Spine C 608 25 Physical and Astral Motion 1 C 612 27 Physical and Astral Motion 2 C 616 29 Physical and Astral Motion 3 C 620 30 Physical and Astral Motion 4 C 626 32 Physical and Astral Motion 5 C 627 34 Physical and Astral Motion 6 C 635 35 Physical and Astral Motion 7 C 636 37 iii Page Cosmic Fire 22 C 643 39 Cosmic Fire 23 C 644 -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

1513923609M6q3development

Items Description of Module Subject Name Human Resource Management Paper Name Indian Perspectives on Human Quality Development Module Title Development of Panch Kosha Module Id Module no- 6 Pre- Requisites HQD- Introduction, Indian Thought Traditions, Perspective on Self Management Objectives To understand what is Panchkosha To study various attributes of Panchkosha To learn the steps towards development or refinement of Panchkosha Keywords Panch Kosha, Annamaya Kosha, Pranamaya Kosha, Manomaya Kosha, Vigyanamaya Kosha, Anandamaya Kosha QUADRANT- III Resources / Learn More 1. References Brad (2014) “Koshas: Sheathes of Being” available online at http://www.slideshare.net/rootlock/koshas Dalal, A.K. and Misra, G. (2010) “The core and context of Indian psychology”, Psychology & Developing Societies, Vol. 22 No. 1, p. 121-155 Iyengar, P. (2017) “Noble Deeds & Meditation work on the Subtle Body”, available online at http://yogatherapysolutions.com/solutions.php Kiran, M. (2010), “Integral education and its (implications) for teacher education”, Educational Quest, Vol. 1 No. 1 Mishra, S. and Chatterjee, A. (2010) “A pancha kosha view of knowledge management”, Global Journal of Enterprise Information System, Vol. 1 No. 2, p. 38-46 Mukherjee, S. (2011) “Indian management philosophy”, in Luk Bouckaert and Laszlo Zsolnai (Eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Spirituality and Business, Vol. 80, Palgrave MacMillan. Sahdev, J.K (2015) “Koshas: Yogic Sheaths of Our Being”, available online at http://savy- international.com/yoga-education/yoga-teacher-training/koshas/ Salagame, K. K. K. (2006) “Health and well-being in Indian traditions”, Psychological Studies, 51(2 & 3), 105–12. Sinha, D. & Naidu, R. K. (1994) “Multilayered hierarchical structure of self and not self: The Indian perspectives”, In A. -

All Computer Applications Need to Store and Retrieve Information

MyFS: An Enhanced File System for MINIX A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of MASTER OF ENGINEERING ( COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY & APPLICATIONS ) By ASHISH BHAWSAR College Roll No. 05/CTA/03 Delhi University Roll No. 3005 Under the guidance of Prof. Asok De Department Of Computer Engineering Delhi College Of Engineering, New Delhi-110042 (University of Delhi) July-2005 1 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “MyFS: An Enhanced File System for MINIX” submitted by Ashish Bhawsar in the partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of degree of Master of Engineering in Computer Technology and Application, Delhi College of Engineering is an account of his work carried out under my guidance and supervision. Professor D. Roy Choudhury Professor Asok De Head of Department Head of Department Department of Computer Engineering Department of Information Technology Delhi College of Engineering Delhi College of Engineering Delhi Delhi 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is a great pleasure to have the opportunity to extent my heartiest felt gratitude to everybody who helped me throughout the course of this project. I would like to express my heartiest felt regards to Dr. Asok De, Head of the Department, Department of Information Technology for the constant motivation and support during the duration of this project. It is my privilege and owner to have worked under the supervision. His invaluable guidance and helpful discussions in every stage of this thesis really helped me in materializing this project. It is indeed difficult to put his contribution in few words. I would also like to take this opportunity to present my most sincere regards to Dr. -

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon the Theosophical Seal a Study for the Student and Non-Student

The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon The Theosophical Seal A Study for the Student and Non-Student by Arthur M. Coon This book is dedicated to all searchers for wisdom Published in the 1800's Page 1 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION PREFACE BOOK -1- A DIVINE LANGUAGE ALPHA AND OMEGA UNITY BECOMES DUALITY THREE: THE SACRED NUMBER THE SQUARE AND THE NUMBER FOUR THE CROSS BOOK 2-THE TAU THE PHILOSOPHIC CROSS THE MYSTIC CROSS VICTORY THE PATH BOOK -3- THE SWASTIKA ANTIQUITY THE WHIRLING CROSS CREATIVE FIRE BOOK -4- THE SERPENT MYTH AND SACRED SCRIPTURE SYMBOL OF EVIL SATAN, LUCIFER AND THE DEVIL SYMBOL OF THE DIVINE HEALER SYMBOL OF WISDOM THE SERPENT SWALLOWING ITS TAIL BOOK 5 - THE INTERLACED TRIANGLES THE PATTERN THE NUMBER THREE THE MYSTERY OF THE TRIANGLE THE HINDU TRIMURTI Page 2 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon THE THREEFOLD UNIVERSE THE HOLY TRINITY THE WORK OF THE TRINITY THE DIVINE IMAGE " AS ABOVE, SO BELOW " KING SOLOMON'S SEAL SIXES AND SEVENS BOOK 6 - THE SACRED WORD THE SACRED WORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Page 3 The Theosophical Seal by Arthur M. Coon INTRODUCTION I am happy to introduce this present volume, the contents of which originally appeared as a series of articles in The American Theosophist magazine. Mr. Arthur Coon's careful analysis of the Theosophical Seal is highly recommend to the many readers who will find here a rich store of information concerning the meaning of the various components of the seal Symbology is one of the ancient keys unlocking the mysteries of man and Nature. -

Virtualization Technologies Overview Course: CS 490 by Mendel

Virtualization technologies overview Course: CS 490 by Mendel Rosenblum Name Can boot USB GUI Live 3D Snaps Live an OS on mem acceleration hot of migration another ory runnin disk alloc g partition ation system as guest Bochs partially partially Yes No Container s Cooperati Yes[1] Yes No No ve Linux (supporte d through X11 over networkin g) Denali DOSBox Partial (the Yes No No host OS can provide DOSBox services with USB devices) DOSEMU No No No FreeVPS GXemul No No Hercules Hyper-V iCore Yes Yes No Yes No Virtual Accounts Imperas Yes Yes Yes Yes OVP (Eclipse) Tools Integrity Yes No Yes Yes No Yes (HP-UX Virtual (Integrity guests only, Machines Virtual Linux and Machine Windows 2K3 Manager in near future) (add-on) Jail No Yes partially Yes No No No KVM Yes [3] Yes Yes [4] Yes Supported Yes [5] with VMGL [6] Linux- VServer LynxSec ure Mac-on- Yes Yes No No Linux Mac-on- No No Mac OpenVZ Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes (using Xvnc and/or XDMCP) Oracle Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes VM (manage d by Oracle VM Manager) OVPsim Yes Yes Yes Yes (Eclipse) Padded Yes Yes Yes Cell for x86 (Green Hills Software) Padded Yes Yes Yes No Cell for PowerPC (Green Hills Software) Parallels Yes, if Boot Yes Yes Yes DirectX 9 Desktop Camp is and for Mac installed OpenGL 2.0 Parallels No Yes Yes No partially Workstati on PearPC POWER Yes Yes No Yes No Yes (on Hypervis POWER 6- or (PHYP) based systems, requires PowerVM Enterprise Licensing) QEMU Yes Yes Yes [4] Some code Yes done [7]; Also supported with VMGL [6] QEMU w/ Yes Yes Yes Some code Yes kqemu done [7]; Also module supported -

Vivekachudamani

Adi Sankaracharya’s VIVEKACHUDAMANI Important Verses Topic wise Index SR. No Topics Verse 1 Devoted dedication 1 2 Glory of Spiritual life 2 3 Unique graces in life 3 4 Miseries of the unspiritual man 4 to 7 5 Means of Wisdom 8 to 13 6 The fit Student 14 to 17 7 The four qualifications 18 to 30 8 Bhakti - Firm and deep 31 9 Courtesy of approach and questioning 32 to 40 10 Loving advice of the Guru 41 to 47 11 Questions of the disciple 48 to 49 12 Intelligent disciple - Appreciated 50 13 Glory of self - Effort 51 to 55 14 Knowledge of the self its - Beauty 56 to 61 15 Direct experience : Liberation 62 to 66 16 Discussion on question raised 67 to 71 i SR. No Topics Verse 17 Gross body 72 to 75 18 Sense Objects, a trap : Man bound 76 to 82 19 Fascination for body Criticised 83 to 86 20 Gross body condemned 87 to 91 21 Organs of perception and action 92 22 Inner instruments 93 to 94 23 The five Pranas 95 24 Subtle body : Effects 96 to 101 25 Functions of Prana 102 26 Ego Discussed(Good) 103 to 105 27 Infinite love - The self 106 to 107 28 Maya pointed out 108 to 110 29 Rajo Guna - Nature and Effects 111 to 112 30 Tamo Guna - Nature and effects 113 to 116 31 Sattwa Guna - Nature and effects 117 to 119 32 Causal body - its nature 120 to 121 33 Not - self – Description 122 to 123 ii 34 The self - its Nature 124 to 135 SR.