Download 'Meeting Places'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nnual Parish Meeting Minutes May 2019

MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL PARISH MEETING OF THEBERTON AND EASTBRIDGE PARISH COUNCIL HELD IN THE JUBILEE HALL, THEBERTON ON WEDNESDAY 8TH MAY 2019 AT 7:00 PM 1. Attendance: Cllr. Stephen Brett (Chair), Cllr. Hilary Ward (Vice-Chair), Cllr. Phillip Baskett, Cllr. Paul Collins, Cllr. Stephen Morphey, Cllr. Graham Bickers, County Cllr. Richard Smith, Sharon Smith (Clerk/RFO) and 5 members of the public. 2. Apologies: Cllr. Beth Goose and Cllr. Julian Wallis. 3. Annual Reports a) Parish Council – Cllr. Stephen Brett read out his report (Appendix A). b) Suffolk County Council - Cllr. Richard Smith read out his report (Appendix B). c) East Suffolk Council – no report submitted due to the recent election. d) Hall Management Committee – no report submitted. e) St Peter’s Church – Cllr. Stephen Brett read out the report on behalf of Simon Ilett (Appendix C). f) Bell Tower - Cllr. Stephen Brett read out the report on behalf of Julia Brown (Appendix D). g) Minsmere Levels Stakeholders Group – Cllr. Paul Collins read out his report (Appendix E). h) Sizewell Parishes Liaison Group – Cllr. Paul Collins read out the report on behalf of Roy Dowding (Appendix F). i) Theberton and Eastbridge Action Group on Sizewell – Alison Downes read out her report (Appendix G). j) Eastbridge Petanque Club - Hilary Ward read out the report on behalf of Martin Inglis (Appendix H). k) Craft Club – Joan Harvey read out her report (Appendix I). l) Carpet Bowls Club – Joan Harvey read out her report (Appendix J). m) Coastliners Line Dance Club – Joan Harvey read out the report on behalf of Mary Drew (Appendix K). -

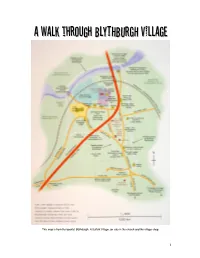

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

Walk 9 - a Walk to the Past

Woodhall Spa Walks No 9 Walk 9 - A walk to the past Start from Royal Square - Grid Reference: TF 193631 Approx 1 hour This route takes the walker to the ruins of Kirkstead Abbey, (dissolved by Henry VIII over 300 years before Woodhall Spa came into being) and the little 13th Century Church of St Leonards. From Royal Square, take the Witham Road, towards the river, passing shops and houses until fields open out to your left. Soon after, look for the entrance to Abbey Lane (to the left). Follow this narrow lane. You will eventually cross the Beck (see also walks 6 and 7) as it approaches the river; the monks from the Abbey once re-routed it to obtain drinking water. Ahead, on the right, is Kirkstead Old Hall, which dates from the 17th Century. Following the land, you cannot miss the Abbey ruin ahead. All that remains now is part of the Abbey Church, but under the humps and bumps of the field are other remains that have yet to be properly excavated, though a brief exploration before the laqst war revealed some of the magnificence of the Cistercian Abbey. Beyond is the superb little Church of St Leonards ( the patron saint of prisoners), believed to have been built as a Chantry Chapel and used by travellers and local inhabitants. The Cistercians were great agriculturalists and wool from the Abbey lands commanded a high price for its quality. A whole community of craftsmen and labourers would have grown up around the Abbey as iut gained lands and power. -

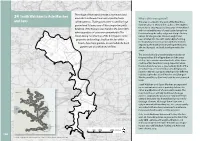

Weavers' Way Short Walk 10 (Of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms

S10 Weavers’ Way Short Walk 10 (of 11) Halvergate to Berney Arms www.norfolktrails.co.uk Version Date: December 2013 Along the way Walk summary A walk through the flat open landscape of Halvergate Marshes, rich with wildlife and windmills, that ends at one of the most The route begins in the village of Halvergate and leads along Marsh Road past the thatched Red remote railway stations in the country. Lion pub out onto the Halvergate Marshes. The marshes were part of a great estuary in Roman times but the area was drained and settled in the early medieval period and now makes up the Getting started largest expanse of grazing marsh in East Anglia. The whole area is designated as a site of This walk starts in Halvergate at Squires special scientific interest and has several international designations too. The marshes support Road/Marsh Road junction (TG420069) and ends internationally important numbers of wintering Bewick’s swan and populations of other waders at Berney Arms rail station (TG460053). and wildfowl that include ruff, golden plover, lapwing, bean goose, European white-fronted goose and wigeon. Other species breeding on Halvergate Marshes include snipe, oystercatcher, yellow Getting there Train Berney Arms Rail Station request stop on wagtail and bearded tit; short-eared and barn owls are frequent winter visitors. limited service. More trains on Sundays. National Rail enquiries: 08457 484950. A little less than a mile out of Halvergate, the Weavers’ Way leads away from the road and along www.nationalrail.co.uk a path to cross Halvergate Fleet, a salt marsh watercourse that the former road to Yarmouth Bus service used to run along until the construction of the Acle New Road (Acle Straight) in the 1830s. -

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

February 2019 Newsletter

for Issue Feb 2019 Connecting Communities ince becoming leader of Suffolk County Council, I have continued to keep broadband at the top of my agenda. I am pleased to tell you that the Better Broadband for Suffolk program has Sreached a new milestone, 93% of homes and businesses across Suffolk can now upgrade to a Superfast Broadband service. This is fantastic news and means an overwhelming majority of residents, businesses and organisations can now enjoy the benefits of faster and more reliable internet speeds. But as a resident and a councillor of a rural ward where some premises still do not enjoy these benefits, I know we have further to go. We already have a contract in place for Openreach to extend fibre broadband coverage to 98% of all Suffolk premises by 2020. But even beyond this, we are committed to reaching 100% Superfast Broadband coverage in Suffolk as quickly as possible. So, if you haven’t already done so, check if Superfast Broadband is available where you live by following the simple steps below, but don’t forget, even if broadband is available, you will need to upgrade your connection to enjoy the benefits of the higher speeds. I look forward to updating you on our future progress. Cllr. Matthew Hicks Leader of Suffolk County Council and Cabinet Member for Economic Development and Infrastructure Here are three simple steps to upgrade Step 1 Finding out whether Better Broadband is available to your postcode Visit our website at www.betterbroadbandsuffolk.com/upgrade-now. Just having the ability to connect doesn’t mean you automatically have Superfast Broadband. -

The Northern Clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace Keith Altazin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Altazin, Keith, "The northern clergy and the Pilgrimage of Grace" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 543. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/543 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NORTHERN CLERGY AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Keith Altazin B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2003 August 2011 Acknowledgments The completion of this dissertation would have not been possible without the support, assistance, and encouragement of a number of people. First, I would like to thank the members of my doctoral committee who offered me great encouragement and support throughout the six years I spent in the graduate program. I would especially like thank Dr. Victor Stater for his support throughout my journey in the PhD program at LSU. From the moment I approached him with my ideas on the Pilgrimage of Grace, he has offered extremely helpful advice and constructive criticism. -

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary

Broads (2006) IDB Water Level Management Plans: Summary WLMP Date reviewed Agreed (Lou WLMP Title (with Author Board Designated Site Designation Mayer/Clive English Doarks) Nature) SSSI, SAC, SPA, Calthorpe Broad RAMSAR, Heidi Brograve 2001 2005 Broads IDB NNR Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Upper Thurne Broads Catfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harding & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Mike Chapelfield 2001 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, Harding RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Halvergate Marshes , SPA, RAMSAR, Heidi SSSI, SAC, Mahon / Halvergate 2000 2005 Broads IDB Damgate Marshes SPA, Sandie RAMSAR, Tolhurst SSSI, SAC, Decoy Carr , SPA, RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, Burgh Common SPA, Muckfleet Marshes RAMSAR, Hemsby and John 2000 2005 Broads IDB SSSI, SAC, Muckfleet Harpley Hall Farm Fen SPA, RAMSAR Trinity Broads SSSI, SAC SSSI, SAC, Priory Meadows , SPA, Heidi RAMSAR, Hickling 2001 2005 Broads IDB Mahon SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Horning 1998 2005 Broads IDB Alderfen Broad SPA, Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Horsefen 1999 2005 Broads IDB Harpley Heigham Marshes RAMSAR, NNR SSSI, SAC, Upper Thurne Broads SPA, John & Marshes Horsey 2000 2005 Broads IDB RAMSAR,s Harpley Winterton To Horsey SSSI, SAC Dunes SSSI, SAC, Ludham Bridge John 1999 2005 Broads IDB Ant Broads & Marshes SPA, East Harpley RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Upper Thurne Broads Martham 2002 2005 Broads IDB SPA, Harpley & Marshes RAMSAR, SSSI, SAC, John Ludham – Potter SPA, Potter Heigham -

ARCHAEOLOGY in SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980� Compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross

ARCHAEOLOGY IN SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980 compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross Once again this is a selection of the new sites and finds discovered during the year. All the siteson this list have been incorporated into the County's Sites and Monuments Index; the reference to this is the final number given in each entry, preceded by the abbreviation S.A.U. Information for this list has been contributed by Miss E. Owles, Moyses Hall Museum; Mr C. Pendleton, Mildenhall Museum; Mr A. Pye, Lowestoft Archaeological Society; and Mr D. Sherlock. The drawings of the axes from Covehithe were kindly supplied by Mr P. Durbridge. Abbreviations: I. M. Ipswich Museum L.A.S. Lowestoft Archaeological and Local History Society M.H. MoysesHall Museum, Bury St Edmunds M.M. Mildenhall Museum S.A.U. Suffolk Archaeological Unit, Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds T.M. Thetford Museum Pa Palaeolithic AS Anglo-Saxon Me Mesolithic MS Middle Saxon Ne Neolithic LS Late Saxon BA Bronze Age Md Medieval IA Iron Age PM Post-Medieval RB Romano-British UN Period unknown Aldringham (TM/4760). Ne. Flaked flint axe, found in a garden several years ago. (F. B. Macrae; S.A.U. ARG 008). Aldringham (TM/4759). Md. The disturbed remain.s of a skeleton, lying in an east-west grave, were found in a gas mains service trench at the end of the archway between the Thorpeness Almshouses. At least one other skeleton was intact beneath it and there may have been more. These are probably associated with the medieval St Mary's Chapel, Thorpe, which formerly existed in that area. -

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - January 2019 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1754 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1754 1900 Aldringham, Particular Baptist Baptist 1809 1837 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1650 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1754 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1650 1900 Bardwell, Baptist Baptist 1820 1837 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1650 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1650 1899 Barnby, St John the Baptist Lothingland 1813 1900 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1730 1902 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1650 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1650 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1663 1901 01 January 2019 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2019 Page 1 of 16 Baptism Register -

Headon-Cum-Upton, Grove & Stokeham Parish Council

Headon-cum-Upton, Grove & Stokeham Parish Council. Minutes of the Meeting of the Parish Council held at Headon-cum-Upton Village Hall 19:30hr on Monday 2nd September 2019. Present:- Parish Councillors; John Mosley, Nigel Greenhalgh, Eric Briggs, Janet Askew and Sean Whelan. Chair:- Parish Councillor. Julia Harvey. Clerk and RFO:- Jim Blaik. District Councillor:- Anthony Coultate. Guests:- None. Members of the public:-Three. Apologies:- Parish Councillor Ben Wielgus. Public forum. RESOLVED to note that no issues raised. 1.Welcome and introduction. Cllr Julia Harvey opened the meeting and welcomed Parish Councillors, District Coun- cillor and Members of the Public to the meeting. 2.Declaration of interests. RESOLVED to note that there were no declarations of interests. 3.New Clerk. RESOLVED to note this item was originally listed as agenda item twenty however, it was agreed to move the item to item three on the agenda. This also resulted in the Minute numbers being different from the published Agenda numbering. The new Clerk was wel- comed and ratification of the new Clerk appointment was agreed by all Councillors pre- sent. The new Clerk commenced on the 2nd September 2019. 4.Minutes of Meeting held on the 1st July 2019. RESOLVED to note the minutes were passed as a true record proposed by Cllr. Julia Harvey, seconded by Cllr. John Mosley. 5.Matters arising. RESOLVED to note confirmation that the Parish Council Agendas and Minutes are dis- played on the Bassetlaw DC Open Data web site up to and including July 2019. 1 of 5 RESOLVED to note that a discussion took place regarding the sourcing of planters de- signed and built at Rampton Hospital, The possible location and sizes of the planters through the parish.