Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Suppression of Communism, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Instrumentality of Fear During Apartheid

THE SUPPRESSION OF COMMUNISM, THE DUTCH REFORMED CHURCH, AND THE INSTRUMENTALITY OF FEAR DURING APARTHEID. SAMUEL LONGFORD: 3419365 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR PARTICIA HAYES i A mini-thesis submitted for the degree of MA in History University of the Western Cape November 2016. Supervisor: Professor Patricia Hayes DECLARATION I declare that The Suppression of Communism, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Instrumentality of Fear during apartheid is my own work and has not been submitted for any degree or examination in any other university. All the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by complete references. NAME: Samuel Longford: 3419365 DATE: 11/11/2016. Signed: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. This mini-thesis has been carried out in concurrence with a M.A. Fellowship at the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR), University of the Western Cape (UWC). I acknowledge and thank the CHR for providing the funding that made this research possible. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CHR. Great thanks and acknowledgement also goes to my supervisor, Prof Patricia Hayes, who guided me through the complicated issues surrounding this subject matter, my partner Charlene, who put up with the late nights and uneventful weekends, and various others who contributed to the workings and re-workings of this mini-thesis. iii The experience of what we have of our lives from within, the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves in order to account for what we are doing, is fundamentally a lie – the truth lies outside, in what we do.1 1 Slavoj Zizek¸ Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (London: Profile Books, 2008): 40. -

Leaders in Grassroots Organizations

Crossing Boundaries: Bridging the Racial Divide – South Africa Taught by Rev. Edwin and Organized by Melikaya Ntshingwa COURSE DESCRIPTION This is a contextual theology course based on the South African experience of apartheid, liberation and transformation, or in the terms of our course: theological discourses from South Africa on “bridging the racial divide”. The course has developed over years – its origins go back to the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre of which the course founder, Dr Judy Mayotte was a Board member. We will look first at the South African experience of Apartheid and try to understand how it was that Christians came to develop such a patently evil form of governance as was Apartheid. We will explore several themes that relate to Apartheid, such as origins, identity, experience, struggle and separation. Then you will have a chance to examine your own theology, where it comes from and how you arrived at your current theological position. In this regard the course also contains sources that deal with Catholic approaches to identity and race. Together we shall then explore issues relating to your own genesis, identity, experience, struggle and separation – all issues common to humankind! All of this we will do by seeking to answer various questions. Each question leads to discussion in class and provides the basis for the work you will be required to do. In the course we examine the nature of separateness (apartheid being an ideology based on a theology of separateness). We will explore the origins of separateness and see how it effects even ourselves at a most basic and elementary level. -

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics Edited by Clifton Crais and Thomas Mcclendon

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2014/04/02/book-review-the-south-africa-reader-history-culture-politics/ Book Review: The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics edited by Clifton Crais and Thomas McClendon The South Africa Reader represents an extraordinarily rich guide to the history, cultures, and politics of South Africa. With more than eighty absorbing selections, the Reader aims to provide readers with many perspectives on the country’s diverse peoples, its first two decades as a democracy, and the forces that have shaped its history and continue to pose challenges to its future, particularly violence, inequality, and racial discrimination. Jason Hickel finds this gripping reading and a comprehensive treatment of the country’s exciting past and tumultuous present – a must for any eager student of South Africa. The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Clifton Crais and Thomas McClendon. Duke University Press. December 2013. Find this book: If there’s one book that succeeds in drawing the many strands of South Africa’s rich political history together into a single volume, this is it. Historians Clifton Crais and Thomas McClendon have accomplished a remarkable feat with The South Africa Reader , which offers more than 80 diverse selections: everything from poetry, folklore, songs and speeches to reportage, scholarly analysis, and a series of powerful photographs that bring it all to life. This symphony of texts and images is laid out in a clear narrative structure that guides readers through the early years of colonial settlement, the mineral revolution, the struggle against apartheid, and the transition to democracy. -

Redalyc.Bona Spes

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Gatti, José Bona Spes Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 61, julio-diciembre, 2011, pp. 11-27 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348699001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative http//dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2011n61p011 BONA Spes José Gatti Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná The main campus of the University of Cape Town is definitely striking, possibly one of the most beautiful in the world. It rests on the foot of the massive Devil’s Peak; not far from there lies the imposing Cape of Good Hope, a crossroads of two oceans. Accordingly, the university’s Latin motto is Bona Spes. With its neo- classic architecture, the university has the atmosphere of an enclave of British academic tradition in Africa. The first courses opened in 1874; since then, the UCT has produced five Nobel prizes and it forms, along with other well-established South African universities, one of the most productive research centers in the continent. I was sent there in 2009, in order to research on the history of South African audiovisual media, sponsored by Fapesp (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo). -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: a Review Essay and Annotated Bibliography 37

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: A Review Essay and Annotated Bibliography 37 Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: A Review Essay and Annotated Bibliography1 Kevin Avruch and Beatriz Vejarano Since 1973, more than 20 “truth commissions” have been established around the world, with the majority (15) created between 1974-1994. Some were created by international organizations like the United Nations (UN), a few by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the majority by the national governments of the countries in question. Counting “Commissions of Inquiry” with “Truth and Reconciliation” commissions, a partial list is as follows: The UN sponsored, financed, and staffed the truth commissions in El Salvador (1992-1993). Commissions sponsored by NGOs include Rwanda (1993) and Paraguay (1976). In South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) sponsored two commissions of inquiry (1992 and 1993) investigating its own conduct during the anti- Apartheid struggle. The better-known South African Commission of Truth and Reconciliation was established by South Africa’s post-Apartheid parliament in 1995; the Commission’s report was issued in October, 1998. Other governmentally sponsored commissions (several of which never published final reports) include Argentina (1983- 1984, resulting in the powerful report Nunca Mas, “Never Again,” translated into English and published commercially in 1986 in Britain and the U.S.); Bolivia (1982-1984; disbanded without issuing a final report); Uruguay (1985); Zimbabwe (1985, report never publicly released); Chile (1990-1991); Chad (1991-1992); Germany (1992-1994); Guatemala (1997-1999); Haiti (1995-1996); Nigeria (1999); Philippines (1986, report never completed); Sierra Leone (called for in 1999, still underway); Uganda (1974 and 1986-1995); Brazil (1986); East Timor (1999-2000); Ethiopia (1993-2000); and Honduras (1993). -

Country of My Skull/Skull of My Country: Krog and Zagajewski, South Africa and Poland

Country of my skull/Skull of my country: Krog and Zagajewski, South Africa and Poland Phil van Schalkwyk School of Languages Potchefstroom Campus North-West University POTCHEFSTROOM E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Country of my skull/Skull of my country: Krog and Zagajewski, South Africa and Poland In the ninth poem of the cycle “land van genade en verdriet” (“country of grace and sorrow”) in the collection “Kleur kom nooit alleen nie” (“Colour never comes on its own”), Antjie Krog contends that the old is “stinking along” ever so cheerfully/ robustly in the new South African dispensation. This could also hold true for the new democratic Poland. Krog and the Polish poet Adam Zagajewksi could, in fact, be described as “intimate strangers”, specifically with regard to the mirrored imagery of “country of my skull”/“skull of my country” present in their work. The notion of “intimate strangers” may be seen as pointing toward the feminine dimension of subjectivity, which could be elaborated along the lines of Bracha Ettinger’s concept of “matrixial borderlinking”. Ettinger has made a significant contribution to the field of psychoanalysis, building on Freud and Lacan. She investigates the subject’s relation to the m/Other, and the intimate matrixial sharing of “phantasm”, “jouissance” and trauma among several entities. Critical of the conventional “phallic” paradigm, Ettinger turns to the womb in exploring the “borderlinking” of the I and the non-I within the matrix (the psychic creative “borderspace”). With these considerations as point of departure, and with specific reference to the closing poem in Krog’s “Country of my skull” and Zagajewski’s “Fire” (both exploring “weaning” experiences in recent personal and public history), I intend to show how the Literator 27(3) Des./Dec. -

History 1886

How many bones must you bury before you can call yourself an African? Updated December 2009 A South African Diary: Contested Identity, My Family - Our Story Part D: 1886 - 1909 Compiled by: Dr. Anthony Turton [email protected] Caution in the use and interpretation of these data This document consists of events data presented in chronological order. It is designed to give the reader an insight into the complex drivers at work over time, by showing how many events were occurring simultaneously. It is also designed to guide future research by serious scholars, who would verify all data independently as a matter of sound scholarship and never accept this as being valid in its own right. Read together, they indicate a trend, whereas read in isolation, they become sterile facts devoid of much meaning. Given that they are “facts”, their origin is generally not cited, as a fact belongs to nobody. On occasion where an interpretation is made, then the commentator’s name is cited as appropriate. Where similar information is shown for different dates, it is because some confusion exists on the exact detail of that event, so the reader must use caution when interpreting it, because a “fact” is something over which no alternate interpretation can be given. These events data are considered by the author to be relevant, based on his professional experience as a trained researcher. Own judgement must be used at all times . All users are urged to verify these data independently. The individual selection of data also represents the author’s bias, so the dataset must not be regarded as being complete. -

Mary Benson's at the Still Point and the South African Political Trial

Safundi The Journal of South African and American Studies ISSN: 1753-3171 (Print) 1543-1304 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsaf20 Stenographic fictions: Mary Benson’s At the Still Point and the South African political trial Louise Bethlehem To cite this article: Louise Bethlehem (2019) Stenographic fictions: Mary Benson’s AttheStillPoint and the South African political trial, Safundi, 20:2, 193-212, DOI: 10.1080/17533171.2019.1576963 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2019.1576963 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 08 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 38 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsaf20 SAFUNDI: THE JOURNAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES 2019, VOL. 20, NO. 2, 193–212 https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2019.1576963 Stenographic fictions: Mary Benson’s At the Still Point and the South African political trial Louise Bethlehem Principal Investigator, European Research Council Project APARTHEID-STOPS, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel ABSTRACT KEYWORDS From the mid-1960s onward, compilations of the speeches and trial South African political trials; addresses of South African opponents of apartheid focused atten- Mary Benson; the Holocaust; tion on the apartheid regime despite intensified repression in the Eichmann trial; wake of the Rivonia Trial. Mary Benson’s novel, At the Still Point, multidirectional memory transposes the political trial into fiction. Its “stenographic” codes of representation open Benson’s text to what Paul Gready, following Foucault, has analyzed as the state’s “power of writing”: one that entangles the political trialist in a coercive intertextual negotiation with the legal apparatus of the apartheid regime. -

AD1844-Bd8-3-3-01-Jpeg.Pdf

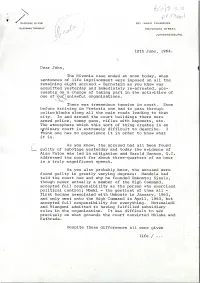

h(d\h 3 . 5 pi 621 INNES CHAMBERS, PRITCHARD STREET, JOHANNESBURG. ,12th June, 1964. Dear John, The Rivonia case ended at noon today, when sentences of life imprisonment were imposed on all the remaining eight accused - Bernstein as you know was acquitted yesterday and immediately re-arrested, pre sumably on a charge of taking part in the activities of one of our"unlawful organizations. 'v- ^ There was tremendous tension in court. Even before arriving in Pretoria one,had to pass through police blocks along all the main roads leading to that city. In and around the court buildings there were armed police, tommy guns, rifles with bayonets, etc. The atmosphere which this sort of thing creates in an cprdinary court is extremely difficult to describe. I tfhink one has to experience it in order to know what it is. /' As you know, the accused had all been found I— guilty of sabotage yesterday and today the evidence of Alan Paton was led in mitigation and Harold Hanson, Q.C. addressed the court for about three-quarters of an hour in a truly magnificent speech. As you also probably know, the accused were found guilty in greatly varying degrees: Mandela had told the court how and why he founded Umkonto; Sisulu, though never actually a member of the High Command, accepted full responsibility as the person who exercised political control; Mbeki - the gentlest of them all - first became associated with Umkonto in January, 1963, and only went onto the High Command in April, 1963, but accepted full responsibility for everything. -

The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 5 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa STEPHEN ELLMANN Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation STEPHEN ELLMANN, The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Stephen Ellmann The Struggle for the Rule of Law in South Africa 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 57 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Stephen Ellmann is Martin Professor of Law at New York Law School. The author thanks the other presenters, commentators, and attenders of the “Courts Against Corruption” panel, on November 16, 2014, for their insights. www.nylslawreview.com 57 THE STRUGGLE FOR THE RULE OF LAW IN SOUTH AFRICA NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 I. INTRODUCTION The blight of apartheid was partly its horrendous discrimination, but also its lawlessness. South Africa was lawless in the bluntest sense, as its rulers maintained their power with the help of death squads and torturers.1 But it was also lawless, or at least unlawful, in a broader and more pervasive way: the rule of law did not hold in South Africa.