Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

THE ONTARIO CURRICULUM, GRADES 9 to 12 | First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies

2019 REVISED The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies The Ontario Public Service endeavours to demonstrate leadership with respect to accessibility in Ontario. Our goal is to ensure that Ontario government services, products, and facilities are accessible to all our employees and to all members of the public we serve. This document, or the information that it contains, is available, on request, in alternative formats. Please forward all requests for alternative formats to ServiceOntario at 1-800-668-9938 (TTY: 1-800-268-7095). CONTENTS PREFACE 3 Secondary Schools for the Twenty-first Century � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �3 Supporting Students’ Well-being and Ability to Learn � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �3 INTRODUCTION 6 Vision and Goals of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � � � � � � � �6 The Importance of the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Citizenship Education in the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Curriculum � � � � � � � �10 Roles and Responsibilities in the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Program � � � � � � �12 THE PROGRAM IN FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS, AND INUIT STUDIES 16 Overview of the Program � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �16 Curriculum Expectations � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Tukitaaqtuq Explain to One Another, Reach Understanding, Receive Explanation from the Past and the Eskimo Identification Canada System

Tukitaaqtuq explain to one another, reach understanding, receive explanation from the past and The Eskimo Identification Canada System by Norma Jean Mary Dunning A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta ©Norma Jean Mary Dunning, 2014 ABSTRACT The government of Canada initiated, implemented, and officially maintained the ‘Eskimo Identification Canada’ system from 1941-1971. With the exception of the Labrador Inuit, who formed the Labrador Treaty of 1765 in what is now called, NunatuKavat, all other Canadian Inuit peoples were issued a leather-like necklace with a numbered fibre-cloth disk. These stringed identifiers attempted to replace Inuit names, tradition, individuality, and indigenous distinctiveness. This was the Canadian governments’ attempt to exert a form of state surveillance and its official authority, over its own Inuit citizenry. The Eskimo Identification Canada system, E- number, or disk system eventually became entrenched within Inuit society, and in time it became a form of identification amongst the Inuit themselves. What has never been examined by an Inuk researcher, or student is the long-lasting affect these numbered disks had upon the Inuit, and the continued impact into present-day, of this type of state-operated system. The Inuit voice has not been heard or examined. This research focuses exclusively on the disk system itself and brings forward the voices of four disk system survivors, giving voice to those who have been silenced for far too long. i PREFACE This thesis is an original work by Norma Dunning. The research project, of which this thesis is a part, received research ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name: “Tukitaaqtuq (they reach understanding) and the Eskimo Identification Canada system,” PRO00039401, 05/07/2013. -

Naming in Inuit Communities: the Attack on Tradition with the Goal of Assimilation

0 Naming in Inuit Communities: The Attack on Tradition with the Goal of Assimilation Jenna Stewart 0669425 Dr. Martha Walls HIST 2210 30 November 2016 1 First came a desire to tame the North. The Canadian government had relatively little to do with its northern territories for a prolonged period of time and minimal contact with the Inuit people who had lived there for countless generations. Inuit communities spanned all the Canadian territories, Northern Quebec and some parts of Newfoundland and Labrador. The Inuit had built lives in the snow and ice embracing the cold temperatures. Their cultures and traditions that were unique to communities; and unique to the Inuit people as a whole. Like the majority of cultures, the tradition of naming held great importance in identifying who a person was within their community. Although, like many cultures differed from the European style of naming. The Inuit names proved difficult for Canadian government official to record or pronounce. As such, two large projects, one a reaction to the first, were implemented by the government to try and solve this, so called, problem. The first one being a disc identification system that started in the early 1940s. Which gave each Inuk a small disc that would be their form of identification. After issues arose eventually there was a new program put in place called “Project Surname”, one of Project Surname’s goals was the elimination of the disc identification system. These programs were implemented without thought or consideration to the Inuit culture and traditions. Along with the Inuit not being considered Aboriginal people, at the time, the Canadian federal and provincial/territorial governments did not treat them as full citizens. -

New Films from Germany

amherstcinema FEB - APR 28 Amity St. Amherst, MA 01002 • www.amherstcinema.org • 413.253.2547 2020 See something different! In addition to the special events in this newsletter, Amherst Cinema shows current-release film on four screens every day. Visit amherstcinema.org and join our weekly e-newsletter for the latest offerings. films of Kelly Reichardt In anticipation of the March 2020 opening of her new movie, FIRST COW, Amherst Cinema is pleased to present four films from the back catalog of director Kelly Reichardt. Reichardt's dramas are small-scale symphonies; alchemical transmogrifications of the ordinary into gripping cinematic experiences. Often collaborating with the same creatives across multiple pictures, such as actor Michelle Williams and writer Jonathan Raymond, Reichardt's films turn the WENDY AND LUCY lens on those in some way at the margins of American communities. Be it a woman living out of her car in WENDY AND LUCY, a group of lost 1840s pioneers in MEEK'S CUTOFF, a reclusive ranch hand in CERTAIN WOMEN, or a hand-to-mouth ex-hippie in OLD JOY, Reichardt's characters, regardless of life circumstances, are deeply and richly human. There may be no other living filmmaker who so fully realizes Roger Ebert's assertion that "movies are the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts." All of which is to say nothing of her films' painterly cinematography, naturalistic and immersive sound design, and Reichardt's knack of scouting the perfect space for every scene, often in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest. Reichardt and her work have been honored at the Cannes Film Festival, the Venice Film Festival, the BFI MEEK'S CUTOFF London Film Festival, the Film Independent Spirit Awards, and more. -

The Legacy of Books Galore

The conversations must go on. Thank You. To the Erie community and beyond, the JES is grateful for your support in attending the more than 100 digital programs we’ve hosted in 2020 and for reading the more than 100 publications we’ve produced. A sincere thank you to the great work of our presenters and authors who made those programs and publications possible which are available for on-demand streaming, archived, and available for free at JESErie.org. JEFFERSON DIGITAL PROGRAMMING Dr. Aaron Kerr: Necessary Interruptions: Encounters in the Convergence of Ecological and Public Health * Dr. Andre Perry - Author of Know you’re your Price, on His Latest Book, Racism in America, and the Black Lives Matter Movement * Dr. Andrew Roth: Years of Horror: 1968 and 2020; 1968: The Far Side of the Moon and the Birth of Culture Wars * Audrey Henson - Interview with Founder of College to Congress, Audrey Henson * Dr. Avi Loeb: Outer Space, Earth, and COVID-19 * Dr. Baher Ghosheh - Israel-U.A.E.-Bahrain Accord: One More Step for Peace in the Middle East? * Afghanistan: When and How Will America’s Longest War End? * Bruce Katz and Ben Speggen: COVID-19 and Small Businesses * Dr. Camille Busette - Director of the Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative and Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution * Caitlin Welsh - COVID-19 and Food Security/Food Security during COVID-19: U.S. and Global Perspective * Rev. Charles Brock - Mystics for Skeptics * Dr. David Frew - How to Be Happy: The Modern Science of Life Satisfaction * On the Waterfront: Exploring Erie’s Wildlife, Ships, and History * Accidental Paradise: 13,000-Year History of Presque Isle * David Kozak - Road to the White House 2020: Examining Polls, Examining Victory, and the Electoral College * Deborah and James Fallows: A Conversation * Donna Cooper, Ira Goldstein, Jeffrey Beer, Brian J. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

A Needs Assessment of Aboriginal Students at the University of Manitoba

A Needs Assesrment of Aboriginal Studenb at the University of Manitoba by J. Jonston-Wakinauk A Practicum Report Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work Program: Clinical Stream Faculty of Social Work University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba (ch National Libray Bibliothèque nationale If1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingion Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OnawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts korn it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othewise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TEIE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRUUATE STUDIES **+** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A Needs Assessment of Aboriginal Students at the University of Manitoba A Thesis/Practicurn submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of ~Manitobain partial tulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Social Work Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend or seU copies of this thesislpracticum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis/practicum and to lend or seU copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to pubiish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. -

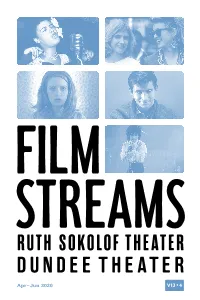

V13 ∙ 4 Apr – Jun 2020

Apr – Jun 2020 V13 ∙ 4 SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT Stay tuned for date and location info (TBD) for all films and events. NEW RELEASES A Note from Film Streams First Cow Dir. Kelly Reichardt — 2019 — USA We hope you are safe and healthy as you read this. As you know, in mid-March 121 min — PG-13 we temporarily closed our cinemas as our community banded together to control A frontier-set meditation on the American Dream the spread and impact of COVID-19. In the following pages, you’ll see the spring — part crime drama, part buddy comedy — that gently subverts Reichardt’s reputation as one of programming we had planned for you prior to our closure. As soon as we can, independent cinema’s most languid storytellers. we’ll be announcing new dates and theater locations for much, if not all, of the programming you see here. As uncertain as this moment feels, this public health crisis affirms what makes our community so special: the people. We are so grateful for the public health Human Nature officials, healthcare workers, and community advocates for their tireless work Dir. Adam Bolt — 2019 — USA — 95 min and dedication for the benefit of our community and country, and enormously appreciative of the Film Streams members and supporters helping our A provocative documentary on the possibilities of the gene editing technology CRISPR, which organization navigate an unprecedented time. opens the door for a variety of interventions in human development. The day will come when we can join together again in the magical experience of watching a movie together in a communal space before a flickering screen. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

First Cow Screenbox

FIRST COW SCREENBOX FICHA NÚM. 2.430 T.O.: FIRST COW NACIONALIDAD: ESTADOS UNIDOS Estreno Screenbox: 21-05-2.021 DURACIÓN: 122’ Estreno España: 21-05-2.021 AÑO: 2.019 WWW.SCREENBOX.CAT TEL: 630 743 981 PI I MARGALL, 26. LLEIDA FICHA ARTÍSTICA FILMOGRAFÍA DE LA Cookie: John Magaro DIRECTORA: Mujer con perro: Alia Shawkat KELLY REICHARDT Trapper Jack: Dylan Smith -First Cow (2.019) Lloyd: Ewen Bremner -Certain Women (2.016) -Night Moves (2.013) FICHA TÉCNICA -Meek's Cutoff (2.010) Directora: Kelly Reichardt -Wendy and Lucy (2.008) Guion: Jonathan Raymond, -Old Joy (2.006) Kelly Reichardt -Ode (1.999) Productores: Neil Kopp, -River of Grass (1.994) Vincent Savino, Anish Savjani Música: William Tyler PREMIOS Y PRESENCIA EN Fotografía: Christopher Blauvelt FESTIVALES (selección) Montaje: Kelly Reichardt -Sección Oficial: Festival de Berlín (2.020) SINOPSIS -Film Independent Spirit Awards: Narra la historia de un cocinero Nominada a la Mejor Película, a la contratado por una expedición de Mejor Dirección y al Mejor Actor de cazadores de pieles, en el estado Reparto (2.021) de Oregón, en la década de 1820. -National Board of Review, Estados También la de un misterioso in- Unidos: Top Ten Films (2.021) migrante chino que huye de unos -Festival de Cine Internacional de hombres que le persiguen, y de la Gijón: Premio a la Mejor Película creciente amistad entre ambos en Sección Albar (2.020) un territorio hostil. ENTREVISTA CON LA DIRECTORA Savjani y Neil Kopp. Ellos son los que están al pie del cañón (extracto) y consiguen que todo sea posible; si estamos grabando una escena y necesitamos que aparezca un pez en el arroyo, ellos ¿Puedes hablarnos del proceso de adaptación están ahí y lo tiran justo a tiempo.