Environmental Hazards and Migrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalization & Crime

Franko-3604-Prelims.qxd 9/19/2007 12:19 PM Page i Globalization & Crime Franko-3604-Prelims.qxd 9/19/2007 12:19 PM Page ii Key Approaches to Criminology The Key Approaches to Criminology series celebrates the removal of traditional barriers between disciplines and brings together some of the leading scholars working at the intersections of different but related fields. Each book in the series aids readers in making intellectual connections across subjects, and highlights the importance of studying crime, criminalization, justice, and punishment within a broad context. The intention, then, is that books published under the Key Approaches banner will be viewed as dynamic and energizing contributions to criminological debates. Globalization & Crime – the second book in the series – is no exception in this regard. In addressing topics ranging from human trafficking and the global sex trade to the protection of identity in cyberspace and post 9/11 anxieties, Katja Franko Aas has cap- tured some of the most controversial and pressing issues of our times. Not only does she provide a comprehensive overview of existing debates about these subjects but she moves these debates forward, offering innovative and challenging ways of thinking about familiar contemporary concerns. I believe that Globalization & Crime is the most important book published in this area to date and it is to the author’s great credit that she explores the complexities of transnational crime and responses to it in a manner that combines sophistication of analysis with eloquence of expression. As one of the leading academics in the field – and someone who is genuinely engaged in dialogue about global ‘crime’ issues at an international level, Katja Franko Aas is ideally placed to write this book, and I have no doubt that it will be read and appreciated by academics around the world. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activ

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activities, and Websites A to G Environmental and Ocean Literacy Environmental literacy is key to preserving the nation's natural resources for current and future use and enjoyment. An environmentally literate public results in increased stewardship of the natural environment. Many organizations are working to increase the understanding of students, teachers, and the general public about the environment in general, and the oceans and coasts in particular. The following are just some of the large-scale and regional initiatives which seek to provide standards and guidance for our educational efforts and form partnerships to reach broader audiences. (In the interest of brevity, please forgive the abbreviations, the abbreviated lists of collaborators, and the lack of mention of funding institutions). The lists are far from inclusive. Please send additional entries for inclusion in future newsletters. Background Documents Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy NAAEE has released Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy, developed by researchers, educators, and assessment specialists in social studies, science, environmental education, and others. A presentation about the framework and accompanying documents are available on this website. http://www.naaee.net/framework Executive Order for the Stewardship of Our Oceans, Coasts, and Great Lakes President Barak Obama signed an Executive Order establishing the National Ocean Council. The Executive Order established for the first time a comprehensive, integrated national policy for the stewardship of the ocean, our coasts, and Great Lakes, which sets our nation on a path toward comprehensive planning for the preservation and sustainable uses of these bodies of water. -

'Silent Arrival': the Second Wave of the Great Migration and Its Affects on Black New York, 1940-1950

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2013 The 'Silent Arrival': The Second Wave of the Great Migration and Its Affects on Black New York, 1940-1950 Carla J. Dubose-Simons The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2231 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE ‘SILENT ARRIVAL’: THE SECOND WAVE OF THE GREAT MIGRATION AND ITS AFFECTS ON BLACK NEW YORK, 1940-1950 by CARLA J. DUBOSE-SIMONS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2013 ii ©2013 Carla J. DuBose-Simons All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Judith Stein, Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Officer Joshua Freeman _____________________________________________ Thomas Kessner ______________________________________________ Clarence Taylor ______________________________________________ George White ______________________________________________ The City University of New York iv ABSTRACT THE ‘SILENT ARRIVAL’: THE SECOND WAVE OF THE GREAT MIGRATION AND ITS AFFECTS ON BLACK NEW YORK, 1940-1950 By Carla J. DuBose-Simons Advisor: Judith Stein This dissertation explores black New York in the 1940s with an emphasis on the demographic, economic, and social effects the World War II migration of blacks to the city. -

12 Family-Friendly Nature Documentaries

12 Family-Friendly Nature Documentaries “March of the Penguins,” “Monkey Kingdom” and more illuminate the wonders of our planet from the safety of your couch. By Scott Tobias, New York Times, April 1, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/arts/television/nature-documentaries-virus.html?smid=em- share Jane Goodall as seen in “Jane,” a documentary directed by Brett Morgen. Hugo van Lawick/National Geographic Creative Children under quarantine are enjoying an excess of “screen time,” if only to give their overtaxed parents a break. But there’s no reason they can’t learn a few things in the process. These nature documentaries have educational value for the whole family, while also offering a chance to experience the great outdoors from inside your living room.Being self-isolated makes one happy to have a project — plus, it would feel good to write something that might put a happy spin on this situation we are in, even if for just a few moments. ‘The Living Desert’ (1953) Disney’s True-Life Adventures series is a fascinating experiment in edu-tainment, an attempt to give nature footage the quality of a Disney animated film, with dramatic confrontations and silly little behavioral vignettes. There are more entertaining examples than “The Living Desert” — the 1957 gem “Perri,” about the plight of a female tree squirrel, is an ideal companion piece for “Bambi” — but it was the company’s first attempt at a feature-length documentary and established a formula that would be used decades down the line. Shot mostly in the Arizona desert, the film marvels over the animals that live in such an austere climate while also focusing on familiar scenarios, like two male tortoises tussling over a female or scorpions doing a mating dance to hoedown music. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, APRIL 5, 2014

TV listings SATURDAY, APRIL 5, 2014 04:15 Storage Hunters 05:20 Scrapheap Challenge 06:10 Extreme Forensics 07:25 Fish Warrior 04:40 Game Of Pawns 06:10 What’s That About? 07:00 I Was Murdered 08:20 Swamp Men 05:05 How Do They Do It? Turbo 07:00 Human Body: Ultimate Machine 07:25 I Was Murdered 09:15 World’s Weirdest: Funny Farms Specials 07:55 Freaks Of Nature 07:50 I Was Murdered 10:10 Moray Eels: Alien Empire 06:00 One Man Army 08:20 Freaks Of Nature 08:15 I Was Murdered 11:05 One Ocean 00:45 Monsters Inside Me 07:00 The Big Brain Theory 08:45 What’s That About? 08:40 Murder Shift 12:00 Hooked 01:35 Untamed & Uncut 00:30 Crime Stories 07:50 Ben Earl: Trick Artist 09:40 What’s That About? 09:30 Murder Shift 12:55 Betty White Goes Wild! 02:25 Shamwari: A Wild Life 01:30 My Ghost Story 08:40 Mythbusters 10:30 What’s That About? 10:20 Murder Shift 13:50 How Human Are You? 02:50 Shamwari: A Wild Life 02:30 Britain’s Darkest Taboos 09:30 Dual Survival 11:20 What’s That About? 11:10 Murder Shift 14:45 America The Wild 03:15 Tanked 03:30 When Life Means Life 10:20 Bear Grylls: Escape From Hell 12:10 What’s That About? 12:00 Disappeared 15:40 Great Migrations 04:05 Treehouse Masters 04:30 Private Crimes 11:10 Yukon Men 13:00 How Tech Works 12:50 Extreme Forensics 16:35 Wild Amazon 04:55 Animal Cops Philadelphia 05:00 Beyond Scared Straight 12:00 Gold Divers: Under The Ice 13:30 Sci-Trek 13:40 Extreme Forensics 17:30 Bears Of Fear Island 05:45 Animal Clinic 06:00 The First 48 12:50 Gold Divers: Under The Ice 14:20 Sci-Trek 14:30 Extreme Forensics -

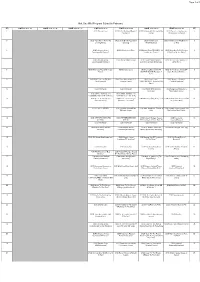

Nat Geo Wild Program Schedule February

Page 1 of 5 Nat Geo Wild Program Schedule February (ET) 月曜日 2018/01/29 火曜日 2018/01/30 水曜日 2018/01/31 木曜日 2018/02/01 金曜日 2018/02/02 土曜日 2018/02/03 日曜日 2018/02/04 (ET) 4 04:00 Swamp Lions 04:00 Safari Brothers[Meerkat 04:00 Triumph of Life「The Mating 04:00 Cesar To The Rescue 4 Madness] Game」 2[Caged And Confused] 5 05:00 Tiger Man of Africa「#3 05:00 Safari Brothers[Leopard 05:00 Animals Gone 05:00 Animals Gone Wild[Believe It 5 Growing Pains」 Spotting] Wild[Ambushed] Or Not] 6 06:00 Ultimate Animal 06:00 Africa's Lost Eden 06:00 Living Edens「BORNEO: An 06:00 Incredible Dr Pol Season 6 Countdown[#3 Swarms] Island in the Clouds」 4[Ruff Day At The Office] 7 07:00 Ultimate Animal 07:00 African Mega Flyover 07:00 Living Edens「KAKADU: 07:00 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER 7 Countdown[#4 Smelliest] Australia's Ancient Wilderness」 2[H2o No! ] 8 08:00 Wild Case Files 2[#2 Kruger 08:00 Swamp Lions 08:00 Living Edens「SOUTH 08:00 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER 8 Killers] GEORGIA ISLAND:Paradise of 2[Let Me Clear My Goat] Ice」 9 09:00 Wild Case Files[#5 Alien 09:00 Tiger Man of Africa「#3 09:00 Living Edens 09:00 America's National 9 Squid Invasion] Growing Pains」 「CANYONLANDS: America's Wild Parks[Yellowstone] West」 10 10:00 information 10:00 information 10:00 Nordic Wild [Ultimate 10:00 Dangerous Encounters 10 Survivors] 「Countdown Crocs」 10:30 SNAKE WRANGLERS 10:30 SNAKE WRANGLERS 「SWIMMING WITH SEA SNAKES」 「SERPENTS OF THE SEA」 11 11:00 Cesar To The Rescue 11:00 Cesar To The Rescue 11:00 Wild Congo[King Kong's Lair] 11:00 Unlikely Animal Friends 3[#3 11 2[Loaded -

National Geographic Channel at 15

SPONSORED CONTENT/AD AGE BREAKING BOUNDARIES National Geographic Channel Marks 15 Years With Bold New Content Opportunities By Julie Liesse erhaps no other cable network has ever arrived on the scene with a brand as powerful and distinctive as National Geographic Chan- nel did in 2001. In 15 years on the air, now reaching 90 million homes in the U.S. and more than 440 million around the world, National Geographic PChannel has both reflected and expanded on the heritage of the 128-year-old National Geographic Society. It’s reflected that heritage with classic science and adventure series and documentaries—as well as spinoff channels Nat Geo WILD and Nat Geo MUNDO—while expanding the brand with new nonfiction offerings such as “Breakthrough,” “Brain Games” and “StarTalk,” and scripted events, including “Saints & Strangers” and the Emmy-nominated “Killing Jesus.” Now the network is preparing to raise the ante with a major commitment to top-flight programming to draw in even more viewers while opening the door to expanded tie-in opportunities for marketers looking to partner with the well-respected brand. This newest stage coincides with the expanded role of 21st Century Fox. Fox and National Geographic Society have been partners for 18 years in owning and operating National Geographic Channels around the globe. But the cre- ation of National Geographic Partners, a joint venture 73% owned by Fox and 27% owned by the National Geographic Society, will allow the TV networks to capitalize on the combined National Geographic and Fox portfolio -

NGC Japan -January 2011

NGC Japan -January 2011 MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 Unbelievable Hour 400 Known Universe 400 Banged Up Abroad 4、Amazing Moments 2、Inside: Afghan ER、Seconds from Disaster 3、 Known Universe → Don't Tell My Mother 2、Mega Breakdown 2、 Great Migrations 430 Air Crash Investigation 6 430 Past disaster TOP5(4th~10th) Gulf Coast Disaster、Naked Science : Iceland Volcano、My 9/11、Trapped、Seconds from Disaster 3 500 500 Future Scenario TOP5(11th~17th) 2012: The Final Prophecy、Naked Science 7、Naked Science 5、Is It Real 2、 2210: The Collapse?(~7:00) Space Special(18th~24th) Wild (R) Engineering Connections、Alien Worlds、Martian Robots、Eclipse、Living on Mars 530 530 Car Special Mega Factories 2、Inside Jaguar 600 Nat Geo Amazing!、 Known Universe、 Apocalypse: The Second World War、 600 Lockdown III、Predator CSI 2 630 630 700 Nat Geo Adventure 700 Long Way Down、World's most Dangerous Drug、Japanese Cowboy、 Nat Geo Amazing! Inside Jerusalem's Holiest、Titanic's Nuclear Secret、Nomads Ski Japan、 730 Boxing Behind Bars、 Crystal Skulls、Dive Detectives、Inside Nirvana 730 New Year SP 1 2 AMERICA'S Sumo Kids DEADLY OBSESSION: Breakout SP 15 SNAKES 800 Breakout 800 「Pittsburgh Six」 Hollywood Voice- over Special 16 Air Crash Eye of the Investigation SP Leopard(~10:00) Science Hour 22 World's Toughest Fixes 2、Naked Science 7、Megastructures:UK Super Train Air Crash Investig Caught in the Act ation 4「Miracle SP 23 Escape」 Caught In The Act 3「#1」 830 29 Bible's Buried 830 Secrets#1 Trapped -

Spectacular Migrations in the Western U.S

Elk Migration © J Burrell, WCS Spectacular Migrations in the Western U.S. Keith Aune Senior Conservation Scientist, Wildlife Conservation Society Elizabeth Williams GIS contractor, Williamson GIS, LLC INTRODUCTION Wildlife migration is a spectacular biological phenomenon that can be witnessed by people around the world. It resonates with our own human history and the migration of people across continents and time. The regular migration of animals, especially birds, has aroused the curiosity of humans since our African genesis. All hunting and gathering societies certainly have known about and perhaps depended upon the movement of animals across land or water. Many cave paintings of animals relay ancient knowledge of animal movements. There are several early written references to the periodic movement of birds in the Bible, and other recorded observations of animal migration date back nearly 3,000 years to the times of Homer, Herodotus, and Aristotle. Humanity has long been aware of the spectacle of animal migration but, until now, had limited understanding of the biological and ecological significance of these migrations. Even today, despite diminished connections between man and nature, the annual synchronized movement of millions of animals captivates the public imagination like few other wildlife phenomenon (Berger 2008). Migration is the seasonal movement of animals (individuals, populations) across land or seascapes that may differ by sex, age, or environmental conditions: yet the core pattern of movement returns to a central area, either by individuals or across generations (Berger et al 2010). It is a complex behavior that is governed by a number of traits that have varying degrees of genetic control and context sensitivity (Bolger et al 2007). -

National Geographic Channel 2013-8

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL August Schedule (ET) Thursday 2013/08/01 Friday 2013/08/02 Saturday 2013/08/03 日曜日 2013/08/04 (ET) 400-430 04:00 Doomsday Preppers「#8 04:00 Doomsday Preppers「#9 04:00 Journey into Amazonia 04:00 Journey into Amazonia 400-430 It's Gonna Get Worse」 Close The Door, Load The 「Waterworlds」 「The Big Top」 430-500 Shotgun」 430-500 (BIL) (BIL) (BIL) (BIL) 500-530 05:00 Dog Whisperer S2 05:00 Dog Whisperer S2 05:00 Journey into Amazonia 05:00 California's Wild Coast 500-530 #17 #18 「The Land Reborn」 530-600 (SUB) (SUB) (BIL) 530-600 (BIL) 600-630 06:00 information 06:00 information 06:00 Dog Whisperer 6 06:00 Dog Whisperer 6 600-630 #4 #6 630-700 06:30 Wild Detectives「Bear() 06:30 Wild() Detectives (SUB) (SUB) 630-700 Meeting」 「Humpback Whales」 700-730 07:00 Winged Seduction: Birds 07:00 Mystery Gorilla 07:00 Dog Whisperer 6 07:00 Dog Whisperer 6 700-730 of Paradise #5 #7 730-800 (BIL) (SUB) (SUB) 730-800 (BIL) 800-830 08:00 Megacities「Sao Paulo」 08:00 Megafactories 08:00 Tiger Queen 08:00 80s: The Decade That 800-830 「Pyrotechnics」 Made Us[#6 Super Power] 830-900 (BIL) (BIL) 830-900 (BIL) (BIL) 900-930 09:00 information 09:00 information 09:00 Sumatra's Last Tiger 09:00 80s greatest[Football 900-930 Moments] 930-1000 09:30 80s greatest[Gadgets]() 09:30 80s greatest[Sporting() (BIL) 930-1000 Icons] (BIL) 1000-1030 (BIL) 10:00 Tiger Man of Africa「#1 10:00 80s greatest[Gadgets] 1000-1030 (BIL) Mating Game, The」 1030-1100 10:30 Animal Autopsy 10:30 Animal Autopsy「Whale」 (BIL) 1030-1100 「Crocodile」 (BIL) 1100-1130 (BIL) -

Re-Imagining Natgeo

Fjord San Francisco 18 June 2013 Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic Hugh Dubberly Dubberly Design Office The National Geographic Society was founded 125 years ago, along the lines of European research societies. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 2 NGS was – and remains – a member-based, non-profit, providing both education and entertainment. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 3 Originally, NGS members pooled resources to fund exploration. Explorers went into the world, collected data, and returned to share their experiences directly with members at NGS meetings in Washington. Members funds Explorers knowledge Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 4 In 1888, the same year NGS was founded, it began publishing a journal to record its research – The National Geographic Magazine. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 5 In 1911, the magazine published a series of photos of Lhasa, Tibet, causing a sensation and selling out. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 6 What began as a happy accident grew into a new type of magazine and then into a publishing empire, changing the relationship between the society and its members. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 7 The brand has deep roots in US culture and has spread around the world. Dubberly Design Office · Engaging members to re-imagine National Geographic · 18 June 2013 8 Now, NGS faces the challenges of “digital convergence” – an existential threat to all traditional media organizations.