Dimensions of Politics in the Czech Republic*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CESES FSV UK Praha 2006 Publisher: CESES FSV UK First Edition: 2006 Editor: Eva Abramuszkinová Pavlíková

Authors: Martin Potůček (Head of the authors‘ team) Eva Abramuszkinová Pavlíková, Jana Barvíková, Marie Dohnalová, Zuzana Drhová, Vladimíra Dvořáková, Pavol Frič, Rochdi Goulli, Petr Just, Marcela Linková, Petr Mareš, Jiří Musil, Jana Reschová, Markéta Sedláčková, Tomáš Sirovátka, Jan Sokol, Jana Stachová, Jiří Šafr, Michaela Šmídová, Zdena Vajdová, Petr Vymětal CESES FSV UK Praha 2006 Publisher: CESES FSV UK First edition: 2006 Editor: Eva Abramuszkinová Pavlíková Graphic design and print: Studio atd. ISSN: 1801-1659 ( printed version) ISSN: 1801-1632 ( on-line version) 3 This paper has been inspired by and elaborated within the research project of the 6th EU Framework programme „Civil Society and New Forms of Governance in Europe – the Making of European Citizenship“ (CINEFOGO – Network of Excellence). Its aim is to gather evidence about the recent development of public discourse, and available literature on civil society, citi- zenship and civic participation in the Czech Republic in order to make it easily accessible to the national as well as international community. The authors’ team was composed according to the scientific interests and research experience of scholars from various Czech universities and other research establishments. It was a challenging task as the paper deals with a broad set of contested issues. The unintended positive effect of this joint effort was the improved awareness of research activities of other colleagues dealing with similar or related research questions. We hope that the paper will encourage both a further comprehensive research of the problem in the Czech Republic and comparative studies across the European Union countries. We are open to critical comments and further discussion about the content of the volume presented here. -

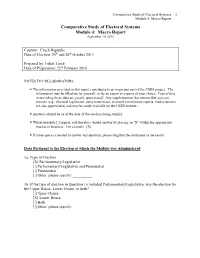

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Czech Republic Date of Election: 25th and 26th October 2013 Prepared by: Lukáš Linek Date of Preparation: 23rd February 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [X] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [X] Lower House [ ] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of Citizens Rights-Zemannites (SPO-Z). -

The Czech President Miloš Zeman's Populist Perception Of

Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 12 Issue 2 DOI 10.2478/jnmlp-2018-0008 “This is a Controlled Invasion”: The Czech President Miloš Zeman’s Populist Perception of Islam and Immigration as Security Threats Vladimír Naxera and Petr Krčál University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Abstract This paper is a contribution to the academic debate on populism and Islamophobia in contemporary Europe. Its goal is to analyze Czech President Miloš Zeman’s strategy in using the term “security” in his first term of office. Methodologically speaking, the text is established as a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS) of a data set created from all of Zeman’s speeches, interviews, statements, and so on, which were processed using MAXQDA11+. This paper shows that the dominant treatment of the phenomenon of security expressed by the President is primarily linked to the creation of the vision of Islam and immigration as the absolute largest threat to contemporary Europe. Another important finding lies in the fact that Zeman instrumentally utilizes rhetoric such as “not Russia, but Islam”, which stems from Zeman’s relationship to Putin’s authoritarian regime. Zeman’s conceptualization of Islam and migration follows the typical principles of contemporary right-wing populism in Europe. Keywords populism; Miloš Zeman; security; Islam; Islamophobia; immigration; threat “It is said that several million people are prepared to migrate to Europe. Because they are primarily Muslims, whose culture is incompatible with European culture, I do not believe in their ability to assimilate” (Miloš Zeman).1 Introduction The issue of populism is presently one of the crucial political science topics on the levels of both political theory and empirical research. -

Twenty Years After the Iron Curtain: the Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010

Twenty Years after the Iron Curtain: The Czech Republic in Transition Zdeněk Janík March 25, 2010 Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic n November of last year, the Czech Republic commemorated the fall of the communist regime in I Czechoslovakia, which occurred twenty years prior.1 The twentieth anniversary invites thoughts, many times troubling, on how far the Czechs have advanced on their path from a totalitarian regime to a pluralistic democracy. This lecture summarizes and evaluates the process of democratization of the Czech Republic’s political institutions, its transition from a centrally planned economy to a free market economy, and the transformation of its civil society. Although the political and economic transitions have been largely accomplished, democratization of Czech civil society is a road yet to be successfully traveled. This lecture primarily focuses on why this transformation from a closed to a truly open and autonomous civil society unburdened with the communist past has failed, been incomplete, or faced numerous roadblocks. HISTORY The Czech Republic was formerly the Czechoslovak Republic. It was established in 1918 thanks to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and his strong advocacy for the self-determination of new nations coming out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the World War I. Although Czechoslovakia was based on the concept of Czech nationhood, the new nation-state of fifteen-million people was actually multi- ethnic, consisting of people from the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), Slovakia, Subcarpathian Ruthenia (today’s Ukraine), and approximately three million ethnic Germans. Since especially the Sudeten Germans did not join Czechoslovakia by means of self-determination, the nation- state endorsed the policy of cultural pluralism, granting recognition to the various ethnicities present on its soil. -

Lustration Laws in Action: the Motives and Evaluation of Lustration Policy in the Czech Republic and Poland ( 1989-200 1 ) Roman David

Lustration Laws in Action: The Motives and Evaluation of Lustration Policy in the Czech Republic and Poland ( 1989-200 1 ) Roman David Lustration laws, which discharge the influence of old power structures upon entering democracies, are considered the most controversial measure of transitional justice. This article suggests that initial examinations of lustrations have often overlooked the tremendous challenges faced by new democracies. It identifies the motives behind the approval of two distinctive lustration laws in the Czech Republic and Poland, examines their capacity to meet their objectives, and determines the factors that influence their perfor- mance. The comparison of the Czech semi-renibutive model with the Polish semi-reconciliatory model suggests the relative success of the fonner within a few years following its approval. It concludes that a certain lustration model might be significant for democratic consolidation in other transitional coun- tries. The Czech word lustrace and the Polish lustrucju have enlivened the forgotten English term lustration,’ which is derived from the Latin term lus- Roman David is a postdoctoral fellow at the law school of the University of the Witwa- tersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ([email protected]; [email protected]). The original version of the paper was presented at “Law in Action,” the joint annual meeting of the Law and Society Association and the Research Committee on the Sociology of Law, Budapest, 4-7 July 2001. The author thanks the University for providing support in writing this paper; the Research Support Scheme, Prague (grant no. 1636/245/1998), for financing the fieldwork; Jeny Oniszczuk from the Polish Constitutional Tribunal for relevant legal mate- rials; and Christopher Roederer for his comments on the original version of the paper. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

By Anders Hellner Illustration Ragni Svensson

40 essay feature interview reviews 41 NATURAL GAS MAKES RUSSIA STRONGER BY ANDERS HELLNER ILLUSTRATION RAGNI SVENSSON or nearly 45 years, the Baltic was a divided Russia has not been particularly helpful. For the EU, sea. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were which has so many member states with “difficult” incorporated into the Soviet Union. Poland backgrounds in the area, the development of a stra- and East Germany were nominally inde- tegy and program for the Baltic Sea has long held high pendent states, but were essentially governed from priority. This is particularly the case when it comes to Moscow. Finland had throughout its history enjoyed issues of energy and the environment. limited freedom of action, especially when it came to foreign and security policies. This bit of modern his- tory, which ended less than twenty years ago, still in- In June 2009, the EU Commission presented a fluences cooperation and integration within the Baltic proposal for a strategy and action plan for the entire Sea area. region — in accordance with a decision to produce The former Baltic Soviet republics were soon in- such a strategy, which the EU Parliament had reached tegrated into the European Union and the Western in 2006. Immediately thereafter, the European defense alliance NATO. The U.S. and Western Europe Council gave the Commission the task of formulating accomplished this in an almost coup-like manner. It what was, for the EU, a unique proposal. The EU had was a question of acting while Russia was in a weake- never before developed strategies applying to specific ned state. -

Biographies of Speakers and Moderators

INTERNATIONAL IDEA Supporting democracy worldwide Biographies of Speakers and Moderators 20 November 2019 Rue Belliard 101, 1040 Brussels www.idea.int @Int_IDEA InternationalIDEA November 20, 2019 The State of Democracy in East-Central Europe Opening Session Dr. Kevin Casas-Zamora, Secretary-General, International IDEA Dr. Casas-Zamora is the Secretary-General of International IDEA and Senior Fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue. He was member of Costa Rica’s Presidential Commission for State Reform and managing director at Analitica Consultores. Previously, he was Costa Rica’s Second Vice President and Minister of National Planning; Secretary for Political A airs at the Organization of American States; Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution; and National Coordinator of the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Report. Dr. Casas-Zamora has taught in multiple higher education institutions. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Oxford. His doctoral thesis, on Political Fi- nance and State Subsidies for Parties in Costa Rica and Uruguay, won the 2004 Jean Blondel PhD Prize of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). Mr. Karl-Heinz Lambertz, President of the European Committee of the Regions Mr. Karl-Heinz Lambertz was elected as President of the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) in July 2017 a er serving as First Vice-President. He is also President of the Parliament of the German-speaking Community of Belgium. His interest in politics came early in his career having served as President of the German-speaking Youth Council. He then became Member of Parliament of the Ger- man-speaking Community in 1981. -

Public Opinion and Democracy In

PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Summer 2014 © 2014 Zofia Maka All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3642337 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3642337 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka Approved: __________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Julio Carrion, Ph.D. -

International Conference Crimes of the Communist Regimes, Prague, 24–25 February 2010

International conference Crimes of the Communist Regimes an assessment by historians and legal experts proceedings Th e conference took place at the Main Hall of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic (24–25 February 2010), and at the Offi ce of the Government of the Czech Republic (26 February 2010) Th e publication of this book was kindly supported by the European Commission Representation in the Czech Republic. Th e European Commission Representation in the Czech Republic bears no responsibility for the content of the publication. © Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, 2011 ISBN 978-80-87211-51-9 Th e conference was hosted by Jiří Liška, Vice-chairman of the Senate, Parliament of the Czech Republic and the Offi ce of the Government of the Czech Republic and organized by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes together with partner institutions from the working group on the Platform of European Memory and Conscience under the kind patronage of Jan Fischer Prime minister of the Czech Republic Miroslava Němcová First deputy chairwoman of the Chamber of Deputies, Parliament of the Czech Republic Heidi Hautala (Finland) Chairwoman of the Human Rights Subcommittee of the European Parliament Göran Lindblad (Sweden) President of the Political Aff airs Committee of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and chairman of the Swedish delegation to PACE Sandra Kalniete (Latvia) former dissident, Member of the European Parliament Tunne Kelam (Estonia) former dissident, Member of the European Parliament -

The Rise and Decline of the New Czech Right

Blue Velvet: The Rise and Decline of the New Czech Right Manuscript of article for a special issue of the Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics on the Right in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe Abstract This article analyses the origins, development and comparative success centre-right in the Czech Republic. It focuses principally on the the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) of Václav Klaus, but also discusses a number of smaller Christian Democratic, liberal and anti-communist groupings, insofar as they sought to provide right-wing alternatives to Klaus’s party. In comparative terms, the article suggests, the Czech centre-right represents an intermediate case between those of Hungary and Poland. Although Klaus’s ODS has always been a large, stable and well institutionalised party, avoiding the fragmentation and instability of the Polish right, the Czech centre- right has not achieved the degree of ideological and organisational concentration seen in Hungary. After discussing the evolution and success of Czech centre-right parties between 1991 and 2002, the article reviews a number of factors commonly used to explain party (system) formation in the region in relation to the Czech centre- right. These include both structural-historical explanations and ‘political’ factors such as macro-institutional design, strategies of party formation in the immediate post-transition period, ideological construction and charismatic leadership. The article argues that both the early success and subsequent decline of the Czech right were rooted in a single set of circumstances: 1) the early institutionalisation of ODS as dominant party of the mainstream right and 2) the right’s immediate and successful taking up of the mantel of market reform and technocratic modernisation. -

The Russian Connections of Far-Right and Paramilitary Organizations in the Czech Republic

Petra Vejvodová Jakub Janda Veronika Víchová The Russian connections of far-right and paramilitary organizations in the Czech Republic Edited by Edit Zgut and Lóránt Győri April, 2017 A study by Political Capital The Russian connections of far-right and paramilitary organizations in the Czech Republic Commissioned by Political Capital Budapest 2017 Authors: Petra Vejvodová (Masaryk University), Jakub Janda (European Values Think Tank), Veronika Víchová (European Values Think Tank) Editor: Lóránt Győri (Political Capital), Edit Zgut (Political Capital) Publisher: Political Capital Copy editing: Zea Szebeni, Veszna Wessenauer (Political Capital) Proofreading: Patrik Szicherle (Political Capital), Joseph Foss Facebook data scraping and quantitative analysis: Csaba Molnár (Political Capital) This publication and research was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. 2 Content Content ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Main findings .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy