The Economic Demography of NT Small Towns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018 Website Facebook Twitter Instagram Visits 15,448 Likes 4,062 Followers 819 Followers 1,225 Artback NT 2018

Annual Report 2018 Website Facebook Twitter Instagram visits 15,448 likes 4,062 followers 819 followers 1,225 Artback NT 2018 Audience Performances NT 19,426 NT 32 National 90,930 National 25 International 1,478 International 3 Total 111,834 Total 60 Workshops Venue by Location NT 236 NT 59 National 13 National 42 International 5 International 6 Total 254 Total 107 Kilometres travelled: Kilometres travelled: exhibition/event people 221,671 1,375,033 Artists/arts workers engaged School events NT 457* 51 National 23 Schools visited International 26 Total 506 17 Indigenous artists/ Media activity arts workers (interviews, articles) 394 69 *68% of NT artists and arts workers engaged were from remote or very remote locations throughout the Northern Territory (this figure excludes Darwin, Katherine, Tennant Creek and Alice Springs). NT regions NT 2018 andattendance location by events NT of number Total Activity Northern Territory • • Artback NT: During 2018 venues 15 across Taiwan and within the Territory Northern delivered were workshops Projects: International venues andremote regional in18urban, groups schoolsandcommunity Territory Artists on Tour: events andrelated workshops 52 including andNumbulwar, inBorroloola festivals Dance: Indigenous Traditional Australia in13galleriesacross public programs Visual Arts: andnationally locally in54venues workshops Arts: Performing included: the organisation Arts across activity the Territory. NorthernIndigenous artist from an for Opportunity Residency Taiwan the as part of venues peoplein6 1,478 of -

Northern Northern Territory

130°0'E 135°0'E Northern Northern Territory !( D A R W I N Native Title Claimant Applications and Determination Areas Northern As per the Federal Court (30 June 2021) Northern RATSIB Boundary Territory Application/Determination boundaries compiled by NNTT based on data sourced Determinations shown on the map include: from and used with the permission of DLPE (NT), - registered determinations as per the National Native Title Register (NNTR), Determined area (NNTT name shown) - determinations where registration is conditional on other matters being finalised. Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Land Tenure 2006. Currency is based on the information as held by the NNTT and may not reflect all Freehold is uncoloured decisions of the Federal Court. Non-freehold land tenure data sourced from DLPE (NT), May 2021. To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an application Aboriginal Freehold or determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and databases is required. As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all Further information is available from the Tribunals website at www.nntt.gov.au or Convertible Lease applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. by calling 1800 640 501 Other Lease © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen While the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT) and the Native Title Registrar Pastoral Lease through the Federal Court. The Tribunal records information on these matters in (Registrar) have exercised due care in ensuring the accuracy of the information the Schedule of Applications (Federal Court). -

Infrastructure Requirements to Develop Agricultural Industry in Central Australia

Submission Number: 213 Attachment C INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIREMENTS TO DEVELOP AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN CENTRAL AUSTRALIA 132°0'0"E 133°0'0"E 134°0'0"E 135°0'0"E 136°0'0"E 137°0'0"E Aboriginal Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Allocation fully economic Requirements Area (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Karlantijpa 1000 20 Tennant ALT Creek + Warumungu $12m $3.94m Frewena ALT 2000 40 (Frewena) 19°0'0"S Frewena 19°0'0"S LIKKAPARTA Tennant Creek Karlantijpa ALT Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements 20°0'0"S (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) 20°0'0"S Illyarne ALT 1500 30 Warrabri ALT 4000 100 $2.9m Western MUNGKARTA Murray $26m (Already Davenport Downs & invested via 1000 ABA $3.5m) Singleton WUTUNUGURRA Station CANTEEN CREEK Illyarne ALT Murray Downs and Singleton Stations ALI CURUNG 21°0'0"S 21°0'0"S WILLOWRA TARA Warrabri ALT AMPILATWATJA WILORA Ahakeye ALT (Community farm) ARAWERR IRRULTJA 22°0'0"S NTURIYA 22°0'0"S PMARA JUTUNTA YUENDUMU YUELAMU Ahakeye ALT (Adelaide Bore) A Potential Potential Approximate Bore Field & B Water LARAMBA Control Aboriginal Land Water jobs when direct Infrastructure C District Trust (ALT) / Area Allocation fully economic Requirements Ahakeye ALT (6 Mile farm) (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) Ahakeye ALT Pine Hill Block B ENGAWALA community farm 30 5 ORRTIPA-THURRA Adelaide bore 1000 20 Ti-Tree $14.4m $3.82m Ahakeye ALT (Bush foods precinct) Pine Hill ‘B’ 1800 20 BushfoodsATITJERE precinct 70 5 6 mile farm 400 10 23°0'0"S 23°0'0"S PAPUNYA Potentia Potential Approximate Bore Field & HAASTS BLUFF Water Aboriginal Control Land Trust l Water jobs when direct Infrastructure District (ALT) / Area Allocati fully economic Requirements on (ML) developed value ($m) ($m) A.S. -

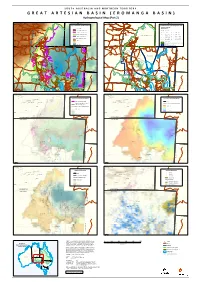

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

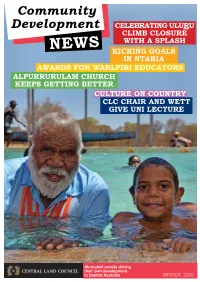

Community Development

Community Development CELEBRATING ULURU CLIMB CLOSURE WITH A SPLASH NEWS KICKING GOALS IN NTARIA AWARDS FOR WARLPIRI EDUCATORS ALPURRURULAM CHURCH KEEPS GETTING BETTER CULTURE ON COUNTRY CLC CHAIR AND WETT GIVE UNI LECTURE Aboriginal people driving their own development in Central Australia WINTER 2020 ANANGU CELEBRATE ULURU CLIMB 2 CLOSURE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS Ngoi Ngoi Donald talking Anangu have used the Uluru climb with ABC journalist and closure to show off what they have CLC staff Patrick Hookey. achieved with their share of the national park’s gate money. On the afternoon before the celebration, “THAT MONEY, WE USE IT doubt about the pool’s popularity. traditional owners gave politicians, senior EVERYWHERE FOR GOOD The families visiting Mutitjulu for the climb public servants and selected media a special ONES: SWIMMING POOL, closure celebration and the midday heat tour of Mutitjulu’s pool and surrounding helped boost the number of swimmers. recreation area. BUSH TRIPS, DIALYSIS, LOTS OF GOOD THINGS Elder Reggie Uluru swapped his wheel chair The chief executive of the National Indigenous for a special lift to cool off in the pool with his Australians Agency, Ray Griggs and some of FOR COMMUNITY,” MS grandson Andre. his colleagues, then NT opposition leader Gary DONALD SAID. He was back refreshed as night descended Higgins and journalists from the ABC and the CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard and on Talinguru Nyakunytjaku (the sunrise Guardian learned that the project has so far community development manager Ian Sweeney viewing area), beating out the rhythm with invested 14 million dollars in more than 100 talked about the history, governance and future two ceremonial boomerangs as Anangu projects in communities across the region. -

Family News 67

Family News Edition 67 Lexi Ward from Aputula and story on pg4 © Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation “ doing good work with families” Postal: PO Box 8274 Alice Springs NT 0871 Location: 3 Ghan Rd Alice Springs NT 0870 Ph: (08) 8953 4488 Fax: (08) 89534577 Website: www.waltja.org.au Waltja Chairperson 2020ngka ngarangu watjil, watjilpa, tjilura, tjiluru nganampa Waltja tjutaku. Ngurra tjutanya patirringu marrkunutjananya ngurrangka nyinanytjaku wiya tawunukutu ngalya yankutjaku. Tjananya watjanu wiya, ngaanyakuntjaku Waltja kutjupa tjutangku tjana patikutu nyinangi Waltjangku, katjangku, yuntalpanku, tjamuku nyaakuntja wiya. Ngurra purtjingka nyinapaiyi tjutanya, Kapumantaku marrkunu tjananya nyinantjaku ngurrangka Tjanaya watjil watjilpa, nyinangi wiya nganana yuntjurringnyi tawunukatu yankutjaku mangarriku, yultja mantjintjaku Waltjalu? Tjanampa yiyanangi yultja tjuta ngurra winkikutu. Tjana yunparringu ngurra winkinya mangarriku Walytjalu yiyanutjangka. Walytjalu yilta tjananya puntura alpamilaningi. Panya Sharijnlu watjanutjangka. Yanangi warrkana tjutanya ngurra tjutakutu. Youth worker, NDIS, culture anta governance tjuta warrkanarripanya Walytjaku kimiti tjutanyalatju tjungurrikula miitingingka wankangi 12 times Member tjutangku miitingingka wangkangi AGM miitingi. Panya minta kuyangkulampa yangatjunu. AGM miitingi ngaraku March-tjingka (2021-ngngka) Nganana yuntjurrinyi minmya tjutaku ngurra tjutaku. Yukarraku, Ulkumanuku, nganana yuntjurringanyi. Palyaya nyinama ngurrangka Walytja tjuta kunpurringamaya. Palya Nangala. 2020 was a hard year, a sad year for people. The remote communities were locked down and no visiting each other. No shopping in Alice Springs. Everyone was crying for warm clothes and food. Oh we were too busy at Waltja clothes and food everywhere! Sending to every community. The rest of the year we were working with Sharijn to do all the programs, help the workers to go bush. Youth work, NDIS, culture and governance work. -

Chapter 9: Northern Territory Intervention and Indigenous Land

Chapter 9 187 Northern Territory intervention and Indigenous land The federal government on 21 June 2007 announced measures to tackle sexual abuse against Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory. The legislation it passed to implement the measures has significant implications for Aboriginal owned and controlled land. This chapter sets out the main provisions in that legislation that affect land. Concerns are identified. A more comprehensive analysis of the intervention in the Northern Territory and human rights is set out in my Social Justice Report 2007. In that report I provide an overview of the main human rights standards and legal obligations relevant to the government’s intervention. In this Native Title Report 2007 I focus on native title and land issues. The areas addressed are: n compulsory five-year leases; n town camps; n effects of other laws; and n rights in construction areas and infrastructure. Overview Legislation giving effect to the Australian Government’s intervention into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory received Royal Assent1 on 17 August 2007. The main provisions dealing with the federal government’s acquisition of rights, titles and interests in land are contained in Part 4 of the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth) (NTNER Act). There are also provisions dealing with infrastructure in Schedule 3 (Infrastructure) of the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Other Legislation Amendment (Northern Territory National Emergency Response and Other Measures) Act 2007 (Cth) (FCSIA(NTNER) Act). That Act amends the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) inserting Part IIB (Statutory rights over buildings or infrastructure). -

Exhibit 4.204.14

ANZ.800.772.0092 Identified ATMs Location No. Site Name Community Locality State 1. Aherrenge Community Store Aherrenge via Alice Springs NT 2. Ali Curung Store Ali Curung NT 3. Mount Liebig Store Mount Liebig NT 4. Aputula Store Aputula via Alice Springs NT 5. Areyonga Supermarket Areyonga NT 6. Arlparra Community Store Utopia NT Atitjere Homelands Store Aboriginal 7. Atitjere NT Corporation 8. Barunga Store Barunga via Katherine NT 9. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation #1 Maningrida NT 10. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation #2 Maningrida NT 11. Belyuen Store Cox Peninsula NT 12. Canteen Creek Store Davenport NT 13. Croker Island Store Minjilang (Crocker Island) NT - - 14. Docker River Store Kaltukatjara (Docker River) NT 15. Engawala Store Engawala NT 16. Finke River Mission Store Hermannsburg via Alice Springs NT 17. Gulin Gulin Store Bulman via Katherine NT 18. lmanpa General Store lmanpa WA via Alice Springs NT NT 19. lninti Store Mutitjulu via Yulara NT 20. Jilkminggan Store Mataranka NT 21. MacDonnel Shire Titjikala Store Titjikala via Alice Springs NT 22. Maningrida Progress Association Maningrida NT 23. Milikapiti Store #1 Milikapiti, Melville Island NT 24. Milikapiti Store #2 Milikapiti, Melville Island NT 25. Nauiyu Store Daly River NT 26. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #1 Bathurst Island NT 27. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #2 Bathurst Island NT 28. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #3 Bathurst Island NT 29. Nguru Walalja Yuendumu NT 30. Nyirripi Community Store Nyirripi NT 31. Papunya Store Papunya via Alice Springs NT 32. Pirlangimpi Store Melville Island NT 33. Pulikutjarra Aboriginal Corporation Pulikutjarra NT 34. Santa Teresa Community Store Santa Teresa NT ANZ.800.772.0093 Location No. -

6 Days Savannah Way, Queensland

ITINERARY Savannah Way, Queensland Queensland – Cairns Cairns – Ravenshoe – Georgetown – Normanton – Katherine AT A GLANCE Drive from Cairns, through Queensland’s yourself in the caves of Undara Volcanic lush Tropical Tablelands and historic National Park, the world’s longest lava > Cairns to Atherton (1.5 hours) goldfields, and across the Northern Territory system. Fossick for gold in historic Croydon > Atherton to Georgetown (4 hours) border to Katherine. Walk through World and Georgetown and spot crocodiles in the Heritage-listed rainforest in Kuranda and wetlands around Normantown. Discover > Georgetown to Normanton (5 hours) explore the produce-rich countryside hidden gorges and Aboriginal rock art in > Normanton to Burketown (3 hours) around Mareeba. Visit a century-old Boodjamulla National Park before crossing Chinese temple in Atherton and spend the Central Gulf into the Northern Territory. > Burketown to Borroloola (7 hours) the night in Ravenshoe, Queensland’s From here, the Savannah Way continues > Borroloola to Katherine (9 hours) highest town. Marvel at Millstream Falls, across the outback all the way to Western Australia’s widest waterfalls and lose Australia’s pearling town of Broome. DAY ONE CAIRNS TO ATHERTON Bushwalk and spot rare native birds in wildlife-rich Tolga Scrub into Atherton, in the Mareeba Wetlands and explore the the heart of the scenic Tropical Tablelands. Drive out of tropical Cairns, on the doorstep volcanic rock formations of Granite Gorge. Walk through rainforest and past miniature of north Queensland’s islands, rainforest See Aboriginal rock art galleries in Davies waterfalls for a top-of-the-tablelands view and reef. Bushwalk, visit Barron Falls and Creek National Park or picnic next to the from Halloran’s Hill. -

51 51 51 in Dealing with These Matters, The

In dealing with these matters, the department The cameras will be a safety tool for officers considers all the circumstances, including the to reduce incidents of complaints and assaults psychological and social needs of the tenancy, and to gather evidence and record antisocial and attempts to engage with tenants to develop behaviour, damage and other issues with public strategies to help them sustain their tenancy. housing premises. This includes referring tenants to tenancy support programs delivered by non-government Central Australia Renal organisations that are funded by the department. Accommodation project The Visitor Management Policy helps the On 22 June 2015, the Australian and Northern department manage public housing visitors. Territory governments struck a $10 million It supports tenants to maintain positive agreement for the delivery of family-centric neighbourhood community relationships, renal accommodation in Alice Springs and manage their private space and protect the Tennant Creek and dialysis infrastructure and quiet environment of their properties and the staff accommodation in Kaltukatjara, Papunya neighbourhood. and Mount Liebig. The renal infrastructure and accommodation will allow better access to renal Terminations and possessions care and accommodation for remote Central of public housing Australian renal patients and their families. Public housing properties are managed in Following a public competitive process, the Central accordance with the Housing Act and the Residential Australian Affordable Housing Company (CAAHC) Tenancies Act. When a tenant breaches their was selected to refurbish and manage 10 homes legal obligations, the department may initiate - eight in Alice Springs and two in Tennant Creek. compliance action, including terminating a tenancy In August 2016, CAAHC started upgrading the THE DEPARTMENT and taking possession of a premises. -

Wallace Rockhole Is Open for Business…

MacDonnell Regional Council Staff Newsletter SEPTEMBER 2015 volume 7 issue 3 Developing supportive communities communitiesLiveable communitiesEngaged A organisation COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL #1 #2 #3 #4 Despite being a small community Wallace Rockhole has always shown great initiative to get things done Wallace Rockhole is open for business… Following the completion of MacDonnell Regional Council’s upgrade of the access road linking Wallace Rockhole to Larapinta Drive, tourists can now drive regular cars to experience the rock art and dot painting tours the community offers. Along with the road upgrade, a recent announcement by the Federal Government to install a mobile phone tower at this and three other communities, in the coming years will add to their accessibility. All this follows Wallace Rockhole being named the first ever community to be awarded a Tidy Town 4 Gold Star Tourism Award, after many years of community support for its cultural tourism infrastructure and services… Find out the latest instalments at Wallace Rockhole and other communities of the MacDonnell Regional Council inside MacDonnell Regional Council Staff Newsletter SEPTEMBER 2015 volume 7 issue 3 page 2 Welcome to MacDonnell Regional Council, CEO UPDATE We have all been very busy since the last MacNews finalising Our Regional Plan, meeting our Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and finishing off another financial year full of improvements to the lives of our residents. At our most recent Council meeting, the KPI Report for the past financial year was presented, showing an outstanding effort across all areas of the MacDonnell Regional Council through some very impressive results.