Loud and Colorful, with Total Recall the Performance Artist Penny Arcade, Now an Actress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

30 24 AWP Full Magazine

Read your local stoop inside. Read them all at BrooklynPaper.com Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2007 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN EDITION AWP /18 pages • Vol. 30, No. 24 • Saturday, June 16, 2007 • FREE INCLUDING DUMBO BABY PRICEY SLICE BANDIT Piece of pizza soaring toward $3 Sunset Parker aids By Ariella Cohen The Brooklyn Paper orphaned raccoon A slice of pizza has hit $2.30 in Carroll Gardens — and the shop’s owner says it’s “just a matter of By Dana Rubinstein time” before a perfect storm of soaring cheese prices The Brooklyn Paper and higher fuel costs hit Brooklyn with the ultimate insult: the $3 slice. A Sunset Park woman is caring for a help- Sal’s Pizzeria, a venerable joint at the corner of less baby raccoon by herself because she Court and DeGraw streets, has punched a huge hole can’t find a professional to take over. in the informal guideline that the price of a slice “I’ve been calling for days, everywhere. I should mirror the price of a swipe on the subway. haven’t gotten no help from no one,” said Mar- Last week, owner John Esposito hung a sign in his garita Gonzalez, who has been feeding the cub front window blaming “an increase in cheese prices” with a baby bottle ever since it wandered into her for the sudden price hike from $2.15, which he set backyard on 34th Street near Fourth Avenue. last year. “I called the Humane Society, and from To bolster his case, Esposito also posted copies of there they have connected me to numbers and a typewritten “update” from his Wisconsin-based / Stephen Chernin cheese supplier, Grande Cheese, explaining that its prices had risen 35 cents a pound because of an “un- precedented” 18-percent spike in milk costs. -

Wr: Mysteries of the Organism Beyond the Liberation of Desire

“THERE IS NOTHING IN THIS HUMAN WORLD OF OURS THAT IS NOT IN SOME WAY RIGHT, HOWEVER DISTORTED IT MAY BE.” WR: MYSTERIES OF THE ORGANISM BEYOND THE LIBERATION OF DESIRE Anarchism, crushed throughout most of the world by the middle of the 20th century, sprang back to life in a variety of different settings. In the US, it reappeared among activists like the Yippies; in Britain, it reemerged in the punk counterculture; in Yugoslavia, where an ersatz form of “self-management” in the workplace was the official program of the communist party, it appeared in a rebel filmmaking movement, the Black Wave. As historians of anarchism, we concern ourselves not only with conferences and riots but also with cinema. Of all the works of the Black Wave, Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism stands out as an exemplary anarchist film. Rather than advertising anarchism as one more product in the supermarket of ideology, it demonstrates a method that undermines all ideologies, all received wisdom. It still challenges us today. up among his workers with his long hair, they would throw him out head first. Even after this debate, the Commission for Cinematography allowed the The struggle of communist partisans against the Nazi occupation provided film, but the public prosecutor banned it the following month. The ban the foundational mythos for 20th-century Yugoslavian national identity. was lifted only in 1986. After the Second World War, the Yugoslavian state poured millions into “I’ve been to the East, and I’ve been to the West, but it was never partisan blockbusters like Battle of Neretva and other sexless paeans to patri- 3. -

Andy Warhol's Factory People

1 Andy Warhol’s Factory People 100 minute Director’s Cut Feature Documentary Version Transcript Opening Montage Sequence Victor Bockris V.O.: “Drella was the perfect name for Warhol in the sixties... the combination of Dracula and Cinderella”. Ultra Violet V.O.: “It’s really Cinema Realité” Taylor Mead V.O.:” We were ‘outré’, avant garde” Brigid Berlin V.O.: “On drugs, on speed, on amphetamine” Mary Woronov V.O.: “He was an enabler” Nico V.O.:” He had the guts to save the Velvet Underground” Lou Reed V.O.: “They hated the music” David Croland V.O.: “People were stealing his work left and right” Viva V.O.: “I think he’s Queen of the pop art.” (laugh). Candy Darling V.O.: “A glittering façade” Ivy Nicholson V.O.: “Silver goes with stars” Andy Warhol: “I don’t have any favorite color because I decided Silver was the only thing around.” Billy Name: This is the factory, and it’s something that you can’t recreate. As when we were making films there with the actual people there, making art there with the actual people there. And that’s my cat, Ruby. Imagine living and working in a place like that! It’s so cool, isn’t it? Ultra Violet: OK. I was born Isabelle Collin Dufresne, and I became Ultra violet in 1963 when I met Andy Warhol. Then I turned totally violet, from my toes to the tip of my hair. And to this day, what’s amazing, I’m aging, but my hair is naturally turning violet. -

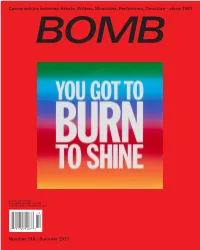

Number 140 / Summer 2017 Conversations Between Artists

Conversations between Artists, Writers, Musicians, Performers, Directors—since 1981 BOMB $10 US / $10 CANADA FILE UNDER ART AND CULTURE DISPLAY UNTIL SEPTEMBER 15, 2017 Number 140 / Summer 2017 A special section in honor of John Giorno John Giorno in front of his Poem Paintings at the Bunker, 222 Bowery, New York City, 2012. Photo by Peter Ross. All images courtesy of the John Giorno Collection, John Giorno Archives, Studio Rondinone, New York City, 81 unless otherwise noted. John Giorno, Poet by Chris Kraus and Rebecca Waldron i ii iii (i) Giorno performing at the Nova Convention, 1978. Photo by James Hamilton. (ii) THANX 4 NOTHING, pencil on 82 paper, 8.5 × 8.5 inches. (iii) Poster for the Nova Convention, 1978, 22 × 17 inches. thanks for allowing me to be a poet electronically twisted and looped his own voice while a noble effort, doomed, but the only choice. reciting his poems. Freeing writing from the page, —John Giorno, THANX 4 NOTHING (2006) Giorno allowed his audiences to step into the physical space of his poems and strongly influenced techno- John Giorno’s influence as a cultural impresario, philan- punk music pioneers like the bands Suicide and thropist, activist, hero, and éminence grise stretches Throbbing Gristle. Yet it’s not Giorno’s use of technol- so widely and across so many generations that one ogy that makes his work memorable, but the sound can almost forget that he is primarily a poet. His work and texture of his voice. The artist Penny Arcade saw is a shining example of how, at their best, poems can him perform at the Poetry Project in 1969, and said, act as a form of public address. -

Horses”—Patti Smith (1975) Added to the National Registry: 2009 Essay by Kimbrew Mcleod (Guest Post)*

“Horses”—Patti Smith (1975) Added to the National Registry: 2009 Essay by Kimbrew McLeod (guest post)* Original album Original label John Cale “Jesus died for somebody’s sins / but not mine,” Patti Smith growled during the opening lines of “Horses,” the first album to emerge from New York City’s punk scene. Released at the end of 1975, it can best be understood by surveying the panorama of influences that shaped its creation: first and foremost, the overlapping underground arts scenes in downtown New York City during the 1960s and 1970s. While “Horses” seemed to emerge fully formed from the mind of a brilliant lyricist and musician, it was also very much the product of an environment that enabled Smith to find her voice. Growing up in a dreamworld filled with poetry and rock ’n’ roll, Smith first fell for Little Richard while living in New Jersey, which introduced her to the idea of androgyny. At age 16, she came across a copy of “Illuminations” by 19th-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud, which expanded her aesthetic horizons. By spring 1967, she graduated from high school and was doing temp work at a textbook factory in Philadelphia, which inspired her early poem-turned-song “Piss Factory,” about having her face shoved into a toilet bowl by bullying coworkers. Smith plotted her escape to New York City, where she landed a much more rewarding job at Brentano’s bookshop and also met Robert Mapplethorpe, who eventually photographed the iconic “Horses” album cover. She and Mapplethorpe became lovers and moved into the Chelsea Hotel, where Smith cultivated social connections that led her to become a performer in underground theater productions around town. -

2017–2018 Annual Report

2017–2018 ANNUAL REPORT GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY PRESERVING FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION OUR PAST, Trustees September 2018 President Mary Ann Arisman Ruth McCoy ENGAGING Arthur Levin Tom Birchard Andrew Paul Dick Blodgett Rob Rogers Vice Presidents Jessica Davis Katherine Schoonover Trevor Stewart Cassie Glover Marilyn Sobel OUR Kyung Choi Bordes David Hottenroth Judith Stonehill Anita Isola Naomi Usher Secretary/Treasurer John Lamb Linda Yowell FUTURE. Allan Sperling Justine Leguizamo F. Anthony Zunino Leslie Mason GVSHP Staff Andrew Berman Harry Bubbins Matthew Morowitz Executive Director East Village & Special Projects Program and Administrative Director Associate Sarah Bean Apmann Director of Research & Ariel Kates Sam Moskowitz Preservation Manager of Communications Director of Operations and Programming Lannyl Stephens Director of Development and Special Events Offices Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation 232 East 11th Street, New York, NY 10003 | T: 212-475-9585 | www.gvshp.org Support GVSHP–become a member or make a donation: gvshp.org/membership Join our e-mail list for alerts and updates: [email protected] Visit our blog Off the Grid (gvshp.org/blog) Connect with GVSHP: Facebook.com/gvshp Flickr.com/gvshp Twitter.com/gvshp Instagram.com/gvshp_nyc YouTube.com/gvshp 3 A NOTE FROM THE PRESIDENT As Andrew Berman our Executive Director I am pleased to report that again this year GVSHP continues to grow by every measure of an reported at our 2018 Annual Meeting this past organization’s success. Especially gratifying is the steady growth in our membership and the critical June, “this has been a real watershed year financial, political and moral support members provide for the organization. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Fine Printing, Artist’s Books, And Books & Manuscripts In Related Fields. Catalogue 329 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

Reviews & Press •

REVIEWS & PRESS J. Hoberman. On Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (and Other Secret-Flix of Cinemaroc). Granary Books, & Hip’s Road, 2001. • Grubbs, David. "Review of On Jack Smith's 'Flaming Creatures.' " Bookforum 9.1: 15. It's a shame that Ted Turner dropped out of the film-colorization business before tackling Flaming Creatures. I'm trying to imagine Jack Smith's washed-out, defiantly low-contrast 1963 film being given the full treatment. Flaming Creatures is the work for which Smith is best known, a film that landed exhibitors in a vortex of legal trouble and quickly became the most reviled of '60s underground features. As J. Hoberman writes, "Flaming Creatures is the only American avant-garde film whose reception approximates the scandals that greeted L'Age d'Or or Zéro de Conduite." Smith's self-described comedy in a "haunted movie studio" is a forty-two-minute series of attractions that include false starts, primping, limp penises, bouncing breasts, a fox-trot, an orgy, a transvestite vampire, an outsized painting of a vase, and perilous stretches of inactivity. The sound track juxtaposes Bartók, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, the Everly Brothers, and an audience-baiting minutes-long montage of screams. Still, one suspects that the greatest trespass may have been putting Smith's queer "creatures" on display. If Hoberman's monograph makes Smith's filmic demimonde less other-worldly—colorizes it, if without the Turner motive—it does so in a manner more akin to the 1995 restoration of Jacques Tati's 1948 Jour de Fête. Tati's film was shot simultaneously in color and in black and white; had the experimental Thomson-Color process worked at the time, it would have been the first French full-length color film. -

Italianità Alternativa Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italianità alternativa Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) Italianità alternativa Joey Skee* (January 28, 2010) “Who, or more precisely, what is an Italian American? To some self-appointed arbiters of italianità, the answer is: Roman Catholic, conservative, and indisputably heterosexual.” If we have learned anything from the ongoing scrutiny of the Italian-American “experience” it is that said experience is any thing but singular. Italian-American histories and cultures are diverse, multifaceted, and ever open to new interpretations and revisions. Author George De Stefano [2] began a 2001 book review in the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute’s social-science journal, the Italian American Review [3] (vol. 8, no.2), with a rhetorical question: “Who, or more precisely, what is an Italian American? To some self-appointed arbiters of italianità, the answer is: Roman Catholic, conservative, and indisputably heterosexual.” If we have learned anything from the ongoing scrutiny of the Italian-American “experience” it is that said experience is any thing but singular. Italian-American histories and cultures are diverse, multifaceted, and ever open to new interpretations and revisions. The Calandra Institute’s public programs offer an opportunity to recognize and represent the diverse expressions of an italianità alternativa. Page 1 of 5 Italianità alternativa Published on iItaly.org (http://ftp.iitaly.org) On October 6, 2009, John Giorno [4] read from his selected works Subduing Demons in America [5] (Soft Skull Press, 2008) as part of the Institute’s Writers Read series. Giorno founded the artist collective Giorno Poetry Systems [6] in 1968, which used technology to make poetry accessible to new audiences and influenced spoken word and slam poetry.