Reviews & Press •

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

RITUALES DE LA TRANSFIGURACIÓN Rubin Filma Enchristmas on Earth Una Orgía En Un Lugar Indeterminado, Fuera Barbara Rubin: Del Tiempo Y El Espacio

Flaming Creatures, 1936. Jack Smith Domingo 18:30 h RITUALES DE LA TRANSFIGURACIÓN Rubin filma enChristmas on Earth una orgía en un lugar indeterminado, fuera Barbara Rubin: del tiempo y el espacio. La doble proyección superpuesta de esta película se Christmas on Earth, 1963, 29 min. desarrolla de manera diferente en cada sesión. Lucifer Rising, por su parte, desarrolla la fascinación de Anger por el ocultismo, Aleister Crowley y la ima- Kenneth Anger: ginería del antiguo Egipto. Esta película generó su propia mitología en torno a Lucifer Rising, 1972, 29 min. los participantes en el rodaje (Marianne Faithfull, el hermano de Mick Jagger o (Copia de Cinédoc París Films Coop) el líder de Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page, entre otros) y a las vicisitudes que sufrió la filmación original. En Flaming Creatures, Smith juega a filmar situaciones Jack Smith: aparentemente inconexas, quizás cercanas a la performance, en una película Flaming Creatures, 1963, 45 min. que valió a su creador un juicio por obscenidad. Proyección en 16 mm Mayores de 18 años 01. Christmas on Earth, por Ara Osterweil Chica judía de clase media del barrio de Queens, [Barbara] Rubin llegó a la comunidad del cine underground de Nueva York cuando solo era una adolescente. A diferencia de la adolescente común, sin embargo, Rubin acababa de salir de un correccional de menores por consumo de drogas, consumo que había iniciado, paradójicamente, después de ingerir un buen puñado de píldoras dietéticas recetadas para con- 01 02 03 trolar su peso. Gracias a su tío, William Rubin, que por aquel entonces dirigía el Gramercy Arts Theater, donde se realizaban muchas proyec- ciones de películas de vanguardia, Barbara conoció a Jonas Mekas, el 03. -

Binghamton Babylon

The Weave 1 Emergence Larry Gottheim: When I arrived at Harpur College in 1964, I was still working on my dissertation, which was on the ideal hero in the realistic novel, focusing on Dostoevsky (The Idiot), George Eliot (Daniel Deronda), and the German Paul Heyse (Kinder der Welt) [The Ideal Hero in the Realistic Novel, Yale University, 1965]—my adviser was the great theoretician René Wellek. After Yale, I’d spent three years at Northwestern University, but I came to Harpur College because it was supposed to be a very special place, the public Swarthmore. And actually, my students at the begin- ning were fantastically literate, more like Yale graduate students than Midwestern undergraduates. Harpur was on a trimester system, which allowed for a lot of flexibility; in fact they were willing to hire me and let me have the first trimester off so I could work on my dissertation. But as soon as I finished my degree and started to face up to the rest of my life, I didn’t feel so comfortable. I was being groomed in the English Department to be the new young scholar/teacher, and I could see my future laid out before me: assistant professor, associate professor, professor—something in me rebelled. Meanwhile, Frank Newman, who, like me, was in the English Department (and much later became the chairman of the Cinema Department for a short period), had started the Harpur Film Society. I wasn’t so involved at the beginning, but I felt a pull. Like everybody else in the humanities, I was interested in Fellini and Godard and the other international directors, through whom we were also discovering the earlier American cinema. -

Queer Icon Penny Arcade NYC USA

Queer icON Penny ARCADE NYC USA WE PAY TRIBUTE TO THE LEGENDARY WISDOM AND LIGHTNING WIT OF THE SElf-PROCLAIMED ‘OLD QUEEn’ oF THE UNDERGROUND Words BEN WALTERS | Photographs DAVID EdwARDS | Art Direction MARTIN PERRY Styling DAVID HAWKINS & POP KAMPOL | Hair CHRISTIAN LANDON | Make-up JOEY CHOY USING M.A.C IT’S A HOT JULY AFTERNOON IN 2009 AND I’M IN PENNy ARCADE’S FOURTH-FLOOR APARTMENT ON THE LOWER EASt SIde of MANHATTan. The pink and blue walls are covered in portraits, from Raeburn’s ‘Skating Minister’ to Martin Luther King to a STOP sign over which Penny’s own image is painted (good luck stopping this one). A framed heart sits over the fridge, Day of the Dead skulls spill along a sideboard. Arcade sits at a wrought-iron table, before her a pile of fabric, a bowl of fruit, two laptops, a red purse, and a pack of American Spirits. She wears a striped top, cargo pants, and scuffed pink Crocs, hair pulled back from her face, no make-up. ‘I had asked if I could audition to play myself,’ she says, ‘And the word came back that only a movie star or a television star could play Penny Arcade!’ She’s talking about the television film, An Englishman in New York, the follow-up to The Naked Civil Servant, in which John Hurt reprises his role as Quentin Crisp. Arcade, a regular collaborator and close friend of Crisp’s throughout his last decade, is played by Cynthia Nixon, star of Sex PENNY ARCADE and the City – one of the shows Arcade has blamed for the suburbanisation of her beloved New York City. -

Tony Conrad Drop by and Visit My Friend La Monte Apartment Probably 14

OK. Hi Tony. Tell us how you ended up at it were; he moved in. So we began to the infamous loft on Ludlow. have a little art colony up there. Then another apartment opened up on the When I was in college I used to actually same floor on the other side of PRL. Tony Conrad drop by and visit my friend La Monte Apartment probably 14. by Will Cameron [Young] in New York between Maryland, where my family lived, and Boston where So Angus [MacLise] managed to get I was going to school. So I would stop this apartment. Of course Angus In April of 2016 one of New York City's most beloved by and visit La Monte who I had met never had any money. So somehow artists, experimental filmmaker and minimalist composer in summer of ‘59 when he was a grad Angus convinced this ruinously Tony Conrad, passed away at the age of 76, leaving student at Berkeley. And in some weird aggressive landlord that he would behind a personal history rich with art, music and stories. way my friend La Monte had actually do a makeover on the apartment and Perfect Wave had a chance to sit down with Tony on January taken up an interest in drugs! It was hard that he would get the first month 22, 2009 at the Sunview Luncheonette on McGolrick Park in to believe and understand, but he shared free for that or something like that. Greenpoint where his studio was located at the time. Over it with me and I found it interesting.. -

Art & Culture 1900-2000 : Part II

WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART The American Century: Art & Culture 1900-2000 Part 11: 1950-2000 The Cool World: Film & Video in America 1950-2000 Curated by Chrissie Iles, curator of film and video, Whitney Museum of American Art. Film Program for the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s co-curated with Mark Webber; 1970s, 1980s and 1990s programs co-curated with Mark MacElhatten, Brian Frye, and Bradley Eros. The Cool Worldsurveys the development of avant-garde film and video in America, from the Beats of the to the 1950s recent innovations of the 1990s. The exhibition includes experiments in abstraction and the emergence of a new, "personal" cinema in the 1950s, the explosion of underground film and multimedia experiments in the 1960s, the rigorous Structural films of the early 1970s, and the new approaches to filmmaking in the 1980s and 1990s. The program also traces the emergence of video as a new art form in the 1960s, its use as a conceptual and performance tool during the 1970s, and its exploration of landscape, spirituality, and language during the 1980s . The Cool World concludes in the 1990s, with experiments by artists in projection, digital technology, and new media. The series is divided into two parts. Part I (September 26-December 5, 1999) presents work from the 1950s and 1960s . Part II (December 7, 1999-February 13, 2000) surveys the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Each month is devoted to a specific decade. All films are 16mm. Those marked (v) are shown on videotape. Asterisked films are shown in both the repeating weekly programs and the Thursday/weekend theme programs. -

The Dialectic of Obscenity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Winter 2012 The Dialectic of Obscenity Brian L. Frye University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brian L. Frye, The Dialectic of Obscenity, 35 Hamline L. Rev. 229 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Dialectic of Obscenity Notes/Citation Information Hamline Law Review, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Winter 2012), pp. 229-278 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/264 229 THE DIALECTIC OF OBSCENITY Brian L. Frye* I. INTRODUCTION 230 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF OBSCENITY 231 A. WHAT IS OBSCENITY? 231 B. THE RISE & FALL OF THE PANDERING TEST 232 C. THE MILLER TEST 234 D. THE AFTERMATH OF MILLER 235 III. FLAMING CREATURES 236 A. THE MAKING OF FLAMING CREATURES 237 B. THE INTRODUCTION OF FLAMING CREATURES 238 C. THE PERSECUTION OF FLAMING CREATURES 242 IV. JACOBS V. NEW YORK 245 A. FLAMING CREATURES IN NEW YORK STATE COURT 245 B. FLAMING CREATURES IN THE SUPREME COURT 250 C. -

30 24 AWP Full Magazine

Read your local stoop inside. Read them all at BrooklynPaper.com Brooklyn’s Real Newspaper BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 834–9350 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2007 BROOKLYN HEIGHTS–DOWNTOWN EDITION AWP /18 pages • Vol. 30, No. 24 • Saturday, June 16, 2007 • FREE INCLUDING DUMBO BABY PRICEY SLICE BANDIT Piece of pizza soaring toward $3 Sunset Parker aids By Ariella Cohen The Brooklyn Paper orphaned raccoon A slice of pizza has hit $2.30 in Carroll Gardens — and the shop’s owner says it’s “just a matter of By Dana Rubinstein time” before a perfect storm of soaring cheese prices The Brooklyn Paper and higher fuel costs hit Brooklyn with the ultimate insult: the $3 slice. A Sunset Park woman is caring for a help- Sal’s Pizzeria, a venerable joint at the corner of less baby raccoon by herself because she Court and DeGraw streets, has punched a huge hole can’t find a professional to take over. in the informal guideline that the price of a slice “I’ve been calling for days, everywhere. I should mirror the price of a swipe on the subway. haven’t gotten no help from no one,” said Mar- Last week, owner John Esposito hung a sign in his garita Gonzalez, who has been feeding the cub front window blaming “an increase in cheese prices” with a baby bottle ever since it wandered into her for the sudden price hike from $2.15, which he set backyard on 34th Street near Fourth Avenue. last year. “I called the Humane Society, and from To bolster his case, Esposito also posted copies of there they have connected me to numbers and a typewritten “update” from his Wisconsin-based / Stephen Chernin cheese supplier, Grande Cheese, explaining that its prices had risen 35 cents a pound because of an “un- precedented” 18-percent spike in milk costs. -

Ron Rice, 1960, 70 Min

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::1a PART::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: La enfermera seguía gritando y tirando de la cámara Dijous 10 de febrer, 20:30 h y pidiendo ayuda. Unos guardianes llegaron corriendo. The Flower Thief, Ron Rice, 1960, 70 min. 16mm. Muy bien, dije yo, caminaré con ustedes hasta la B/N. Sonora. Actor: Taylor Mead. salida. Pero en el corredor, mientras íbamos caminando, al final del corredor, había tres mujeres :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::2a PART:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: sentadas, con aspecto triste y las cabezas inclinadas, Xcèntric tan bellas y tristes que tuve que sacarles una Senseless, Ron Rice, 1962, 28 min. 16 mm. B/N. fotografía, y apreté el disparador. <<¡Deténgalo! CINEMA INVISIBLE Sonora. Música: Bartok, música mexicana i india. ¡Deténgalo! ¡Está fotografiando!>>, gritó el doctor. Muntatge: Howard Everngam. <<¡No puede hacer eso, no puede hacer eso!>>. RON RICE Guanyadora del Charles Theater Film-Makers Entonces trataron de quitarme la cámara. Yo me Festival, juliol 1962. aferré y dije: <<No, no pueden hacer eso. Esto es de mi propiedad>>. Cuando vi que otros dos Chumlum, Ron Rice, 1964, 26 min. 16 mm. Color. guardianes se unían contra mí, puse la cámara sobre Sonora. Música: Angus McLise. Tècnic de so: Tony la mesa y dije: <<Muy bien, aquí está>>. Saqué el Conrad. Ajudant especial: Stanley Alboum. Actors: film de la cámara, lo envolví y lo sellé dentro de su Jack Smith, Beverly Grant, Mario Montez, Joel lata, y le dije al guardian: <<El que lleve este film al Markman, Frances Francine, Guy Henson, Barry <<Village Voice>> tendrá cien dólares de Titus, Zelda Nelson, Gerard Malanga. recompensa>>. Entonces, antes de que tuviera tiempo de darme cuenta, veo que el médico empieza a llenar tarjetas, y en un santiamén me encontré 30 de enero 1964 dentro, junto con las demás bellas y tristes criaturas, en este lugar terrible. -

The Making and Unmaking of Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures A

FILM AT REDCAT PRESENTS Mon Nov 9 | 8:30 pm Jack H. Skirball Series $9 [students $7, CalArts $5] The Making and Unmaking of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures A Screening and Talk with J. Hoberman Los Angeles revival 1963, 16mm, b/w, 45 min. Recognized as an unprecedented visionary masterpiece, Flaming Creatures was also reviled, rioted over, banned as porn, and pondered by the Supreme Court. “Jack Smith described Flaming Creatures as ‘a comedy set in a haunted movie studio.’ It is that, as well as the single most important and influential underground movie ever released in America,” according to J. Hoberman, film critic of The Village Voice for more than 30 years and an authority on the Smith performance and film oeuvre. “Smith’s movie was a source of inspiration for artists as disparate as Andy Warhol, Federico Fellini and John Waters but he never completed another.” Find out why. Hoberman’s books include The Dream Life: Movies, Media and the Mythology of the Sixties and Bridge of Light: Yiddish Cinema Between Two Worlds. Hoberman has authored a 2001 monograph on Flaming Creatures titled, On Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (and Other Secret-Flix of Cinemaroc), as well as numerous articles on Smith, a key figure in the New York underground cinema of the 1960s and a performance art pioneer. Hoberman’s talk will precede a screening of Flaming Creatures, and detail the film’s creative making and legal unmaking on charges of obscenity. Flaming Creatures’ delirium of transgendered eroticism and trashy artifice prompted its first champion Jonas Mekas, then writing in The Village Voice to declare (presciently, as it turned out): “[I]t is so beautiful I feel ashamed to sit through the current Hollywood and European movies... -

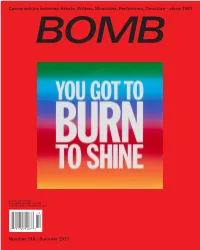

Number 140 / Summer 2017 Conversations Between Artists

Conversations between Artists, Writers, Musicians, Performers, Directors—since 1981 BOMB $10 US / $10 CANADA FILE UNDER ART AND CULTURE DISPLAY UNTIL SEPTEMBER 15, 2017 Number 140 / Summer 2017 A special section in honor of John Giorno John Giorno in front of his Poem Paintings at the Bunker, 222 Bowery, New York City, 2012. Photo by Peter Ross. All images courtesy of the John Giorno Collection, John Giorno Archives, Studio Rondinone, New York City, 81 unless otherwise noted. John Giorno, Poet by Chris Kraus and Rebecca Waldron i ii iii (i) Giorno performing at the Nova Convention, 1978. Photo by James Hamilton. (ii) THANX 4 NOTHING, pencil on 82 paper, 8.5 × 8.5 inches. (iii) Poster for the Nova Convention, 1978, 22 × 17 inches. thanks for allowing me to be a poet electronically twisted and looped his own voice while a noble effort, doomed, but the only choice. reciting his poems. Freeing writing from the page, —John Giorno, THANX 4 NOTHING (2006) Giorno allowed his audiences to step into the physical space of his poems and strongly influenced techno- John Giorno’s influence as a cultural impresario, philan- punk music pioneers like the bands Suicide and thropist, activist, hero, and éminence grise stretches Throbbing Gristle. Yet it’s not Giorno’s use of technol- so widely and across so many generations that one ogy that makes his work memorable, but the sound can almost forget that he is primarily a poet. His work and texture of his voice. The artist Penny Arcade saw is a shining example of how, at their best, poems can him perform at the Poetry Project in 1969, and said, act as a form of public address.