Ketty La Rocca: Word, Image, Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Documentation

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Documenting the user experience AUTHORS Giannachi, G JOURNAL Revista de Historia da Arte DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 October 2015 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/18428 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication REVISTA DE HISTÓRIA /04DA ARTE PERFORMING DOCUMENTATION IN THE CONSERVATION OF CONTEMPORARY ART JOURNAL DIRECTORS (IHA/FCSH/UNL) Raquel Henriques da Silva Joana Cunha Leal Pedro Flor PUBLISHER Instituto de História da Arte EDITORS Lúcia Almeida Matos Rita Macedo Gunnar Heydenreich AUTHORS Teresa Azevedo | Alessandra Barbuto Liliana Coutinho | Annet Dekker | Gabriella Giannachi | Rebecca Gordon | Hélia Marçal Claudia Marchese | Irene Müller | Andreia Nogueira Julia Noordegraaf | Cristina Oliveira | Joanna Philips Rita Salis | Sanneke Stigter | Renée van de Vall 3 5 193 Vivian van Saaze | Glenn Wharton REVIEWERS Heitor Alvelos | Maria de Jesus Ávila EDITORIAL DOSSIER BOOK Marie-Aude Baronian | Helena Barranha Lúcia Almeida Matos REVIEWS Lydia Beerkens | Martha Buskirk Rita Macedo Alison Bracker | Laura Castro Gunnar Heydenreich Carlos Melo Ferreira | Joana Lia Ferreira Tina Fiske | Eva Fotiadi | Claudia Giannetti Amélie Giguère | Hanna Hölling | Ysbrand Hummelen Sherri Irvin | Iris Kapelouzou | Claudia Madeira Julia Noordegraff | Raquel -

ON PAIN in PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das

BEARING WITNESS: ON PAIN IN PERFORMANCE ART by Jareh Das Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London, 2016 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Jareh Das hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19th December 2016 2 Acknowledgments This thesis is the result of the generosity of the artists, Ron Athey, Martin O’Brien and Ulay. They, who all continue to create genre-bending and deeply moving works that allow for multiple readings of the body as it continues to evolve alongside all sort of cultural, technological, social, and political shifts. I have numerous friends, family (Das and Krys), colleagues and acQuaintances to thank all at different stages but here, I will mention a few who have been instrumental to this process – Deniz Unal, Joanna Reynolds, Adia Sowho, Emmanuel Balogun, Cleo Joseph, Amanprit Sandhu, Irina Stark, Denise Kwan, Kirsty Buchanan, Samantha Astic, Samantha Sweeting, Ali McGlip, Nina Valjarevic, Sara Naim, Grace Morgan Pardo, Ana Francisca Amaral, Anna Maria Pinaka, Kim Cowans, Rebecca Bligh, Sebastian Kozak and Sabrina Grimwood. They helped me through the most difficult parts of this thesis, and some were instrumental in the editing of this text. (Jo, Emmanuel, Anna Maria, Grace, Deniz, Kirsty and Ali) and even encouraged my initial application (Sabrina and Rebecca). I must add that without the supervision and support of Professor Harriet Hawkins, this thesis would not have been completed. -

13Th Congress of the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry

Acta Derm Venereol 2009; 89: 551–592 13th Congress of the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista Venice Italy, September 17–22, 2009 www.esdap2009.org Congress President ESDaP Executive Committee: Main Sponsors and Supporters Andrea Peserico Sylvie Consoli (F), President Abbott Immunology Dermatology University Clinic, Padua Françoise Poot (BE), President Elect Schering-Plough Michael Musalek (A), Past President Wyeth Congress Secretary Dennis Linder (I), Secretary Astellas Dennis Linder Klaus-Michael Taube (D), Treasurer Gruenenthal Dermatology University Clinic, Padua John De Korte (NL) Janssen-Cilag Andrew Finlay (UK) Bank Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie Uwe Gieler (D) Gregor Jemec (DK) Regional Psoriasis Reference Centre for Lucía Tomás Aragonés (E) the Region Veneto Jacek Szepietowski (PL) Regional Paediatric Dermatology Refe- rence Centre for the Region Veneto The Congress is endorsed by: University of Padua, Municipality of Venice, European Academy for Dermatology and Venereology, ADIPSO Italian Psoriasis Patient Association, Grupo Español de Dermatología y Psiquiatría, Société Francophone de Dermatologie Psychosomatique (SFDPS), Arbeitsgemeinschaft Psychosomatische Dermatologie, The “Centro Regionale Veneto di Riferimento per la Dermatologia Pediatrica (responsabile: Dr. Anna Belloni Fortina)”, “Centro Regionale Veneto di Riferimento per la Psoriasi (responsabile: Prof. Mauro Alaibac)”, SIDEP – Società Italiana di Dermatologia Psicosomatica, Melacavo – Associazione Italiana Melanoma. -

Restyling Between Conservation and Design

the architecture & interior design international magazine | middle east > italy RESTYLING BETWEEN CONSERVATION AND DESIGN Focus New trends and tradition in China Powerhouse Company, Brian Johnson Neri & Hu Design and Research Office Wang Weijen Architecture, Aurelien Chen COR arquitectos + Flavia Chiavaroli Wael Al-Masri, Fumihiko Sano Studio Year XII nr 035 April 2021 Year of Entry 2008 Four-monthly | ISSN 2409-3823 | Dubai - United Arab Emirates Price: UAE 39 dirham, Bahrain 4,23 dinari, KSA 42,06 riyal, Kuwait 3,45 dinari, Oman 4,32 rial,9,90 Euro. 40,82 rial, Qatar IT Kuwait 42,06 riyal, 4,23 dinari, 39 dirham, Bahrain KSA UAE Price: Emirates Arab - United | ISSN 2409-3823 Dubai of Entry 2008 Four-monthly Year April 2021 XII nr 035 Year ENGLISH / ITALIAN ISSUE the architecture & interior design international magazine | middle east > italy 035 RESTYLING BETWEEN CONSERVATION AND DESIGN Publisher Board Art Director Advertising Sales Director Publisher [editorial] 22 Style, stylism and restyling between conservation and design - Andrea Pane Marco Ferretti Ferdinando Polverino De Laureto Luca Màllamo e.built Srl - Italy e Francesca Maderna Via Francesco Crispi 19-23 Stile, stilismo e restyling tra conservazione e progetto Team and Publishing Coordinator Advertising Sales Agency 80121 Napoli [essays] The conservation of built heritage in Japan: current issues - Mizuko Ugo Scientific Director Sara Monsurró Agicom Srl phone +39 081 2482298 es 25 Andrea Pane [email protected] Viale Caduti in Guerra, 28 fax +39 081 661014 Problematiche -

Artist Books

anntiqdm publicatiom of the Avant Gardes of the 20b ARTIST BOOKS centwy, focusing on the sides and seventies: concept, minimal, land art, meIpovera, happe~ngsmd flm, maill NEWS art, pop art, Vienna Aho~sm,Situationism, Dada, Sumedisrm, ek. PnclualeB Specid representa~oasof sontemporsaay book art aa8 tbe Rmcha, Gerkard Wichkr, Si 52"* FranMw& Book Fair, 18 - 23 October 2080. For the %chard Tuttle, J.L. Byas, M. first time in its history, Fair will provide Eva Messe, DoddJudd, Carl Andre, George Brecht,Daniel a special forum for c art in Wle 3.1, Sprri, Andy Warhol, Dieter RotHa, Jackson Pollock, Bill which will become "Book Art Square7', a place where the Bollinger, Lee Bontecw etc. Searches can be made from the pubEc will enjoy an indep& view of the world of field of Visual Ant Collwtiom, e~bitionpaactice and letterpress-pBinted works, painters' books, a.x%slg books and theory, monographs and especially ephemera, underg~ound book objects. This eve and related materid. Contact Peter Below, lhrt Base. BucNDmcMKunst Inc in Support of Contemnporary The town of Mells in County Meath, Ireland is exerting Contemprary Book Art", an errPlibition ofworld-wide book increasingpressme to be allowed to exhibit the renowned art, "Book Art News Fonun," an overview of offerings from Book of Kells at its supposed place of origin. They are nearly 75 presses and book artists from 14 Merent to bansfom a local codouse into an exhibit hail countries; "One Hundred Words from the 20" century," the book and is considering legal action if its showcasing original examples ofthe ways in which book art request to obtain the work on loan is rehsed by Trinity can interpret text Wo~pXcdly.In addition there will College Dublin, where the Book of Kells lhas resided since be7'Internatiod Book Art'' and "The MstBeautihl Books the 17" century. -

Arengario-2019-Poesia-Visiva-Web

1 Bruno e Paolo Tonini. Fotografia di Tano D’Amico L’ARENGARIO Via Pratolungo 192 STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO 25064 Gussago (BS) Dott. Paolo Tonini e Bruno Tonini ITALIA Web www.arengario.it E-mail [email protected] Tel. (+39) 030 252 2472 Fax (+39) 030 252 2458 2 3 L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO POETICHE DELL’AVANGUARDIA IN ITALIA La pratica del testo nella civiltà dell’ immagine (poesia lineare - tecnologica - visiva - romanzo sperimentale) 1956 - 1981 Nota introduttiva di Lamberto Pignotti Catalogo della mostra Brescia, 17.2. Art Gallery 30 marzo - 14 aprile 2019 EDIZIONI DELL’ARENGARIO 2 3 Nota sull’uso del catalogo Poetiche dell’avanguardia in Italia si inaugura il 30 marzo 2019 presso la 17.2 Art Gallery di Brescia. Le opere e i docu- menti in mostra non sono oggetti da contemplare o da interpretare sulla scorta di chi sa che studi critici. Nella loro stra- nezza e nella evidenza che li assimila alla vita di ogni giorno come all’esperienza di ciascuno, chiedono partecipazione. Sono mezzi di comunicazione diversi dai mass media: non trasmettono un messaggio, ci chiamano a farne parte. Così il catalogo che li raccoglie non è soltanto un elenco con i prezzi, è uno strumento per orientarsi. Non offre risposte, è un aiuto a porsi le giuste domande. Abbiamo ancora bisogno di poesia? Chiediamolo a quelli che oggi non hanno ancora diciotto anni. Nei loro smart phone c’è più poesia che non nelle odiose riesumazioni scolastiche. Chiediamolo a loro che quando ne vengono toccati si ac- corgono che non cercavano altro e che devono cambiare la vita prima che la vita li cambi. -

Salvatore Ferragamo and Twentieth-Century Visual Culture

SALVATORE FERRAGAMO AND TWENTIETH-CENTURY VISUAL CULTURE MUSEO SALVATORE FERRAGAMO PALAZZO SPINI FERONI, FLORENCE 19 MAY 2017 - 2 MAY 2018 UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF WORKSHOP BETWEEN ART AND DESIGN IN ITALY Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali 1927-2017: THE INNOVATION PROJECT e del Turismo by Design Campus, Dipartimento di Architettura- Regione Toscana DIDA, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Comune di Firenze Supervised and curated by professor Francesca Tosi Projects by: Martina Follesa, Serena Gentile, Nadia EXHIBITION PROMOTED AND ORGANIZED BY Gutnikova, Angelo Iannotta, Dalila Innocenti, Margaret Museo Salvatore Ferragamo Nikol Kasynets, Rosario Lo Turco, Matteo Lombardi, in collaboration with Ji Lu, Maria Luisa Malpelo, Francesca Morelli, Giorgia Fondazione Ferragamo Palazzo, Lorenzo Pelosini, Francesca Piccinini, Marco Raffi, Ivan Vecchia EXHIBITION PROJECT CONCEIVED BY Stefania Ricci EXPLANATORY EDUCATIONAL PANELS AND AUDIOGUIDES BY CURATED BY Neri Conti, Olimpia Miniati, Benedetta Noferi, Carlo Sisi Bernardo Sarti, students of Liceo Classico Michelangiolo (IV A) in Florence, supervised by SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE professor Stefano Fabbri Bertoletti within the Lucia Mannini framework of the Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro-MIUR Susanna Ragionieri programme in agreement with Fondazione Ferragamo Stefania Ricci CATALOGUE EDITED BY SCENOGRAPHY Stefania Ricci Maurizio Balò Carlo Sisi in collaboration with Andrea De Micheli CONTENTS BY Alessandra Acocella, Maria Canella, Daniela VIDEO INSTALLATIONS AND VIDEOS Degl’Innocenti, Roberta Ferrazza, -

Download Pdf File

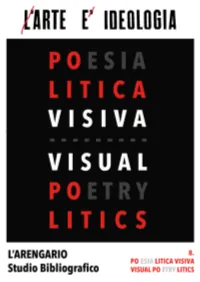

ARTE E IDEOLOGIA 8. │ Po esia litica visuale / Visual po etry litics │ I ___________________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________ ARCHIVIO DELL’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO │ www.arengario.it ORDINI / ORDER │ [email protected] ARTE E IDEOLOGIA 8. │ Po esia litica visuale / Visual po etry litics │ II ___________________________________________________________________________________________ L’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO Via Pratolungo 192 | 25064 Gussago (BS) | ITALIA www.arengario.it | [email protected] | ++390302522472 ARTE E IDEOLOGIA a cura di Paolo Tonini - 8 - PO ESIA LITICA VISIVA VISUAL PO ETRY LITICS 10 luglio 2021 EDIZIONE DIGITALE ___________________________________________________________________________________________ ARCHIVIO DELL’ARENGARIO STUDIO BIBLIOGRAFICO │ www.arengario.it ORDINI / ORDER │ [email protected] ARTE E IDEOLOGIA 8.│ collana│ Po esia a cura litica di /visuale series edited/ Visual by po Paolo etry liticsTonini │ III ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Fernando De Filippi, particolare del poster della mostra Slogan, Milano, Salone Annunciata, 31 gennaio 1979 “Arte e ideologia” è una collana di cataloghi e “Arte e ideologia” [Art and ideology] is a se- monografie di artisti, autori e movimenti che a ries of catalogs and monographs about artists, partire da una riflessione sulle contraddizioni authors and movements which, -

La Parola Intermediale: Un Itinerario Pugliese (Cavallino 25, 26 Maggio 2017)

La parola intermediale: un itinerario pugliese (Cavallino 25, 26 Maggio 2017) a cura di Francesco Aprile e Cristiano Caggiula 2017 CITTÀ DI CAVALLINO BIBLIOTECA COMUNALE “G. RIZZO” -3- © testi 2017: Vincenzo Ampolo, Francesco Aprile, Michele Brescia, Rossana Bucci, Cristiano Caggiula, Marilena Cataldini, Oronzo Liuzzi, Egidio Marullo, Antonio Negro, Francesco Pasca, Alberto Piccinni LA PAROLA INTERMEDIALE: UN ITINERARIO PUGLIESE La rivista di critica e linguaggi di ricerca www.utsanga.it, nata nel settembre 2014 con intenti a carattere storico-critico in quegli ambiti che vedono l’ibridazione, dal secondo Novecento ad oggi, della parola letteraria con i mass-media e le aree extra- letterarie in genere, propone, in collaborazione con la Biblioteca Gino Rizzo di Cavallino, attraverso una due giorni di incontri, la tavola rotonda dal titolo “La parola intermediale: un itinerario pugliese”. Scopo dell’iniziativa è tracciare un resoconto delle esperienze pugliesi che hanno avuto modo di muoversi, dagli anni ’60 ad oggi, negli ambiti di quei linguaggi liminali, ibridi, di derivazione poetica. Dalla poesia concreta alla poesia visiva, dalla mail art alla parola performativa, dalle scritture manuali all’asemic writing, dalla net.poetry al glitch: il contributo pugliese alle ricerche intermediali. Nei giorni 25 e 26 maggio, dalle ore 18:00 presso la Biblioteca Gino Rizzo, a Cavallino (Le) in via Amendola, le ricerche promosse dalla rivista www.utsanga.it incontrano l’impegno, la cura e la promozione che la Biblioteca Gino Rizzo dimostra da tempo in ambito culturale. Nasce un incontro che intreccia l’azione volitiva dell’impegno sul territorio alle ricerche a carattere storico-critico su quei linguaggi che del territorio pugliese sono traccia nel mondo. -

Edited by Nico Vassilakis

::EDITED BY NICO VASSILAKIS:: Was there an experience, a specific interaction with visual poetry that infected your brain, made you see language differently or drew you toward exploring vispo further? Is there a vispoem that captured your imagination. What piece first awakened in you the possibility of a visual alphabet/language alternative? That was the general question posed and here are the results. Though this query is overly reductive, the poets were kind enough to choose, for the most part, a singular vispoem as example of this phenomenon. These replies were first collected in Coldfront Magazine where I was serving as Vispo Editor. Thank you participants. Nico Vassilakis 2016 Participants: Amanda Earl derek beaulieu Michael Peters Anneke Baeten Edward Kulemin Michael Winkler Aram Saroyan Francesco Aprile Miguel Jimenez Barrie Tullett Geof Huth Mike Borkent bill bissett Geoffrey Gatza Orchid Tierney Bill Dimichelle Gleb Kolomiets Patrick Collier Billy Mavreas Jeff T. Johnson Scott Helmes Brandon Downing Jesse Glass serkan_isin Brian Reed Joel Chace Stephen Nelson Carol Stetser Karl Kempton Sven Staelens Clemente Padin KS Ernst Tim Gaze Connie Tettenborn Lawrence Upton Tulio Restrepo Crag Hill Louis Bury Vittore Baroni Demosthenes Luc Fierens W. Mark Sutherland Agrafiotis Mark Young Willard Bohn Denis Smith Márton Koppány Amanda Earl / Mary Ellen Solt Zinnia (1964) by Mary Ellen Solt From her Flowers in Concrete series. Not the first visual poem, I’d ever seen, but most likely the first series that left me gobsmacked, made me want to create visual poetry myself. And also made me interested in the idea of the series in visual poetry. -

Lucia Marcucci, Maestra Verbovisiva

LEA - Lingue e letterature d’Oriente e d’Occidente, n. 4 (2015), pp. 359-371 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/LEA-1824-484x-17711 Lucia Marcucci, maestra verbovisiva Federico Fastelli Università degli Studi di Firenze (<[email protected]>) Abstract This article considers the work of visual-poetry artist and poet Lucia Marcucci. It aims to exemplify the complexity and aesthetic impor- tance of her works. Mischievous irony, political awareness and the unending need for experimentation are but a few of the main qualities of Marcucci’s work identified here. Combined, they entitle this Tuscan artist to be considered one of the masters of her artistic and literary era. Keywords: artist book, Gruppo 70, Lucia Marcucci, Neo-Avant-garde, visual poetry Die ungelösten Antagonismen der Realität kehren wieder in den Kunstwerken als die immanenten Probleme ihrer Form. (Adorno 1970, 16)1 The wide multitude wanted to seem contrarian. It meant that this type of nonconformism had to be mass-produced. (Andy Warhol) Nel 1988 la Cooperativa La Favorita di Verona pubblicava il Catalogo della Mostra itinerante dal titolo Poesia visiva, 1963-1988: 5 maestri..., che inclu- deva, entro tale tassonomica insegna, opere di Ugo Carrega (1935-2014), Stelio Maria Martini (n. 1934), Eugenio Miccini (1925-2007), Lamberto Pignotti (n. 1926) e Sarenco (n. 1945). Innegabili, certo, i motivi delle au- toconsacrazioni a maestri della stagione verbovisiva dei cinque artisti, eppure più che opinabile il tentativo storicizzante, intanto parziale, a dire il vero, in 1 Trad. it. di De Angelis 1977, 11: “Gli irrisolti antagonismi della realtà si ripresentano nelle opere d’ arte come problemi immanenti della loro forma”. -

RARE Periodicals Performance ART, Happenings, Fluxus Etc

We specialize in RARE JOURNALS, PERIODICALS and MAGAZINES rare PeriodicAlS Please ask for our Catalogues and come to visit us at: per fORMANcE ART, HappENINgS, http://antiq.benjamins.com flT UxUS E c. RARE PERIODICALS Search from our Website for Unusual, Rare, Obscure - complete sets and special issues of journals, in the best possible condition. Avant Garde Art Documentation Concrete Art Fluxus Visual Poetry Small Press Publications Little Magazines Artist Periodicals De-Luxe editions CAT. Beat Periodicals 297 Underground and Counterculture and much more Catalogue No. 297 (2017/2018) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT Visiting address: Klaprozenweg 75G · 1033 NN Amsterdam · The Netherlands Postal address: P.O. BOX 36224 · 1020 ME Amsterdam · The Netherlands tel +31 20 630 4747 · fax +31 20 673 9773 · [email protected] JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Prices in this catalogue are indicated in EUR. Payment and billing in US-dollars to the Euro equivalent is possible. 2. All prices are strictly net. For sales and delivery within the European Union, VAT will be charged unless a VAT number is supplied with the order. Libraries within the European Community are therefore requested to supply their VAT-ID number when ordering, in which case we can issue the invoice at zero-rate. For sales outside the European Community the sales-tax (VAT) will not be applicable (zero-rate). 3. The cost of shipment and insurance is additional. 4. Delivery according to the Trade Conditions of the NVvA (Antiquarian Booksellers Association of The Netherlands), Amsterdam, depot nr. 212/1982. All goods supplied will remain our property until full payment has been received.