THREE MONTHS of U. P. I. Relations University of the Witwatersrand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Conscription in South Africa, 1952-1972

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-29 46 PATRIOTIC DUTY OR RESENTED IMPOSITION? PUBLIC REACTIONS TO MILITARY CONSCRIPTION IN WHITE SOUTH AFRICA, 1952-1972 __________________________________ Graeme Callister Department of History, University of Stellenbosch1 Introduction It is widely known that from the introduction of the Defence Amendment Act of 1967 (Act no. 85 of 1967) until the fall of apartheid in 1994, South Africa had a system of universal national service for white males, and that the men conscripted into the South African Defence Force (SADF) under this system were engaged in conflicts in Namibia, Angola, and later in the townships of South Africa itself. What is widely ignored however, both in academia and in wider society, is that the South African military relied on conscripts, selected through a ballot system, to fill its ranks for some fifteen years before the introduction of universal service. This article intends to redress this scholastic imbalance. The period of universal military service coincides with the period that saw South Africa in the world’s spotlight, when defeating apartheid was the great crusade in which capitalist and communist alike could engage. It is therefore not surprising that the military of that era has also been studied. Post-1967 universal national service in South Africa has received some attention from scholars, and is generally portrayed as a resented imposition at best. Resistance to conscription is widely covered, especially through the 1980s when organisations such as the Conscientious Objectors Support Group (COSG, formed in 1980) and the End Conscription Campaign (ECC, formed in 1983) gave a more public ‘face’ to the anti-conscription movement.2 However, as can be seen from the relatively late 1 I would like to extend my gratitude to Professor Albert Grundlingh of the University of Stellenbosch for his comments and advice on the first draft of this article. -

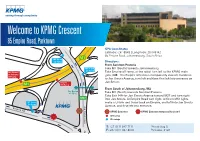

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

The White Opposition Splits

12 THE WHITE OPPOSITION SPLITS STANLEY UYS Political Correspondent of the 'Sunday Times1 THE annual congress of the official South African Parliamentary Opposition or United Party in August last year, on the eve of the Provincial Elections, resulted in the resignation of almost a quarter of its Members of Parliament and the formation of a new white political party—the Progressives. Amidst the exhuma tions and excuses, analyses and adjustments that followed, two highly significant conclusions emerged—the official Parliamentary Opposition has swung substantially to the right, narrowing the already narrow gap between Government and United Party on the doctrines of race rule; and, for the first time in South African history, a substantial white Parliamentary Party with wide, if not dominant, electoral support in many urban areas, had come into existence specifically in order to propagate a more liberal policy in race relations. The origin of the Progressive break must be sought in the right-wing ''rethinking" resulting from the total failure of the United Party to avoid a steady electoral decline during the n years in which it has been in Opposition. In 1948, the Nationalist Party came to power with a majority of fewer than half-a-dozen M.P.s. Today, it has two-thirds of the House of Assembly, partly due to the completely one-sided character of the electoral system (particularly delimitation methods) and partly to the growing numerical superiority of the Afrikaner. It did not take the United Party long to evolve the view that there was no profit in battering its head against a stone wall, and that the only chance of success lay in winning over "moderate'' Nationalist voters. -

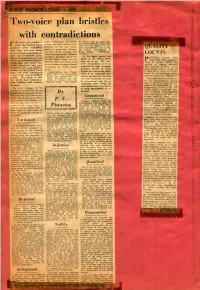

A1132-Ba2-002-Jpeg.Pdf

- ■ m m m Two-voice plan bristles with contradictions N the first two articles I either individuals or racial be shared with all those non- wrote that United Party groups, and apart from a brief Europeans who have shown that I reference to what was clearly they have the capacity to take speakers often contradict joint responsibility with us for each other and even them meant as safeguards between the future development of selves in their statements on the two White sections and South Afriea.” ("Weekblad,” which was made in the "Ordered 1 7 . 3 . 6 1 . ) COUNTS v> their race federation plan. In the tame speech the Advance” pamphlet issued by OLITICAL parties, more | Those contradictions are no leader of the United Party doubt an indication that the Sir De Villiers Graaff on Oc than most other organisa- S tober 25, 1960, I could find little went on to say: "W e want j P! tions of people, reflect the whole plan was rather hur them (the Africans) to be re W , i riedly conceived and pre or no reference to constitutional , quality of human material safeguards in United Party presented by eight European \ j they embody. In other words maturely horn and that the members, elected by those I good people tend to make for f leaders of the United Party policy. Natives who have shown them- ■ | a good party, indifferent j have not even considered Nevertheless the United selves to be responsible citi people for an indifferent party, ï certain vital aspects of their Party has as its main policy plank, the safeguarding of zens of our country." But ham and bad people for a bad party. -

Colin Eglin, the Progressive Federal Party and the Leadership of the Official Parliamentary Opposition, 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987

Journal for Contemporary History 40(1) / Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis 40(1): 1‑22 © UV/UFS • ISSN 0285‑2422 “ONE OF THE ARCHITECTS OF OUR DEMOCRACY”: COLIN EGLIN, THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY AND THE LEADERSHIP OF THE OFFICIAL PARLIAMENTARY OPPOSITION, 1977‑1979 AND 1986‑1987 FA Mouton1 Abstract The political career of Colin Eglin, leader of the Progressive Federal Party (PFP) and the official parliamentary opposition between 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987, is proof that personality matters in politics and can make a difference. Without his driving will and dogged commitment to the principles of liberalism, especially his willingness to fight on when all seemed lost for liberalism in the apartheid state, the Progressive Party would have floundered. He led the Progressives out of the political wilderness in 1974, turned the PFP into the official opposition in 1977, and picked up the pieces after Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s dramatic resignation as party leader in February 1986. As leader of the parliamentary opposition, despite the hounding of the National Party, he kept liberal democratic values alive, especially the ideal of incremental political change. Nelson Mandela described him as, “one of the architects of our democracy”. Keywords: Colin Eglin; Progressive Party; Progressive Federal Party; liberalism; apartheid; National Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leader of the official parliamentary opposition. Sleutelwoorde: Colin Eglin; Progressiewe Party; Progressiewe Federale Party; liberalisme; apartheid; Nasionale Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leier van die amptelike parlementêre opposisie. 1. INTRODUCTION The National Party (NP) dominated parliamentary politics in the apartheid state as it convinced the majority of the white electorate that apartheid, despite the destruction of the rule of law, was a just and moral policy – a final solution for the racial situation in the country. -

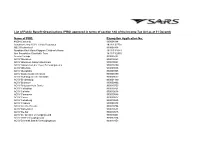

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Johannes De Villiers Graaff1 Johannes De Villiers Graaff, Known

Johannes de Villiers Graaff1 Johannes de Villiers Graaff, known more simply as Jan Graaff, shared with that other great son of the Boland, JM Coetzee, the somewhat terrifying power of silent authority which comes from that mixture of brilliant intelligence combined with surprising shyness. Small talk was not part of his character and he could be a highly intimidating presence to those who met him. But for those, family and friends, who got to know him, he was a warm and wonderful human being and could be a great storyteller. Once, when he was trapped in a window seat on a flight to London and I was in the aisle, I was able to ask him a lot of questions which he could not escape, so I learnt a good deal. Why, for example, was he (whom we lesser mortals all knew to be the greatest economist that South Africa had produced and who loved his discipline) not willing to join the faculty of one of our universities to teach students? His answer was that he had tried teaching in Cambridge and in Harvard but had decided that the internecine departmental politics that he encountered was so offensive that he resolved never to spend his working life in such an environment. And so, Paul Samuelson from MIT, writing in the pages of the Economic Journal in September 1958 when Jannie Graaff was only 30 but had already decided to leave academia, lamented that “economics has lost so able a mind”. Joan Robinson said that he was the brightest PhD student that Cambridge had ever had. -

OD Section (Pdf)

ARE YOU ELIGIBLE FOR A BRITISH PASSPORT? If a parent or grandparent was born in the UK, Ireland or outside of South Africa, then you or your children may qualify for British Nationality. We are the world’s leading experts in UK immigration and nationality. Since 1992, we have helped thousands of South Africans navigate the complex path to British citizenship. Call one of our nationality advisors to find out whether you or your children qualify. e: [email protected] | UK: +44 (0) 207 759 7581 | SA: 021 657 2139 www.philipgamble.co.uk 573560 PG Blue Sky Advert A5.indd 1 2/13/2015 2:01:30 PM June 2015 OD Union 113 OLD DIOCESANS UNION 50 Year Reunion CONTENTS ROLL OF HONOUR 114 NOTES FROM OD UNION OFFICE 117 SOCIAL REGISTER Visitors, births, engagements, marriages, wedding anniversaries and octogenerians 124 OBITUARIES 129 NEWS OF ODs 143 OD UNION SPOrt 151 Class reunions 162 MUSEUM & ARCHIVES 172 OD AGM 173 114 OD Union June 2015 ROLL OF HONOUR Their name liveth for ever In June we remember: THE GREAT WAR 1914-1919 Lawrence (‘Laurie’) Anderson (1909-15) Lieut, RFC. Flanders, 11 June 1917 Gordon Bayley (1902-08) Lieut, Royal Flying Corps. France, June 1914 Edward Bramley (1888-89) Lieut, NLC. France, June 1921 Robert Hunter (1900-07) Lieut, 1st King Edward’s Force. June 1920 Percy Johnstone (1906-08) Trooper. Died of wounds in East Africa, June 1916 Harry Lee (1902-03) Lieut Irish Guards. Died of wounds in France, 18 June 1916 Archibald Mansfield (1902-05) Pvt, 1st SA Infantry. -

NC79 December 2017 Edition.Indb

New Contree, No. 79, December 2017, Book Reviews, pp. 184-197 Die slotbeskouing van die boek is geskryf deur Mamokgethi Setati Phakeng van die Universiteit van Kaapstad. Sy het die hoop uitgespreek dat die boek Good Hope “is the start of a new way of representing the ties between the Netherlands and South Africa … (and that) we can look forward to tracing South African tracks in Dutch culture, political economy and science”. Sy meld dat baie van die bydraes in die boek gefokus het op die impak van Ned- erland op Suid-Afrika. Sy sou graag wou sien dat daar meer aandag geskenk word aan Suid-Afrikaanse invloed op Nederland. Good Hope is ’n baie besondere boek, veral omdat dit die geskiedenis lewen- dig en aanskoulik voorstel. Aan die einde van die boek is daar 20 bladsye inligting oor endnote, ’n uitgebreide bronnelys, ook wat al die illustrasies betref. Bondige inligting oor al die outeurs word ook verskaf. Die boek word van harte aanbeveel vir almal wat in Nederlands-Suid-Afrikaanse betrekkinge belangstel. Iron in the soul: The leaders of the official parliamentary opposition in South Africa, 1910-1993 (Pretoria, Protea Book House, 2017, 224 pp. ISBN 978-1-4853-0550-7) FA Mouton Charmaine T Hlongwane North-West University [email protected] FA Mouton is a renowned historian who has written extensively about South African political history and Afrikaner nationalism. In his recent book Iron in the soul: Leaders of the official parliamentary opposition in South Africa,he analyses the careers of official opposition leaders in the South African parlia- ment between 1910 and 1993. -

Albert Hertzog's “Calvinist Speech” and the Verlig

62 AUTHOR: ALBERT HERTZOG’S “CALVINIST Weronika Muller1 AFFILIATION: SPEECH” AND THE VERLIG- 1Doctoral student, VERKRAMPSTRYD: THE ORIGINS Department of History, OF THE RIGHT-WING MOVEMENT University of South Africa IN SOUTH AFRICA EMAIL: [email protected] DOI: https://dx.doi. ABSTRACT org/10.18820/24150509/ SJCH46.v1.4 This article analyses the role Dr Albert Hertzog, an ultra- conservative Afrikaner Nationalist, played in the formation ISSN 0258-2422 (Print) of South Africa’s right-wing movement. It focuses on ISSN 2415-0509 (Online) his “Calvinist speech” of 1969 due to its historical Southern Journal for significance for the unity of the National Party (NP) and as a broad summary of Hertzog’s personal opinion Contemporary History on the politics of South Africa. The speech contrasted 2021 46(1):62-85 liberal English with Calvinistic Afrikaners and concluded that only an Afrikaner true to Calvinistic principles could PUBLISHED: succeed in leading the nation through the perilous times 23 July 2021 they were facing. This opinion was considered offensive to the English population as well as to “enlightened” Nationalists like the Prime Minister, John Vorster. The article will examine how the controversy surrounding the speech precipitated a split in the NP; those expelled formed a right-wing party that failed to gain considerable support. When apartheid was being dismantled in the early 1990s, the movement did not pose a serious threat to the ruling party despite vows that Afrikaners would never surrender their power but rather fight to the bitter end. The failure of these ultra-conservatives originated in the verlig-verkrampstryd of the 1960s, in which Hertzog played a significant role. -

(Kent) Durr PV647

Inventory of the private collection of KDS (Kent) Durr PV647 Contact Us Write to: Archive for Contemporary Affairs University of the Free State P.O. Box 2320 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa Visit us: Archive for Contemporary Affairs Stef Coetzee Building Room 109 Academic Avenue South University of the Free State 205 Nelson Mandela Drive Park West Bloemfontein Telephone: +27(0)51 401 2418 Email: [email protected] PV647 KDS (Kent) Durr FILE NO SERIES SUB-SERIES DESCRIPTION DATES 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/1/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1983- (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of 1985 files 1983-1985 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/2/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1986 (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of files 1986 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/3/ 1 SUBJECT 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1986- (KENT) FILES Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of 1987 files 1986-1987 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/4/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1989- (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of 1990 files 1989-1990 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/5/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1991 (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of files 1991 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/6/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1992 (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of files 1992 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/7/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1993 (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. of files 1993 647 DURR, KDS 1/1/8/ 1 SUBJECT FILES 1/1 Diaries, correspondence, 1994 (KENT) Chronological newspaper cuttings, notes etc. -

The Rise of the South African Reich

The Rise of the South African Reich http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp3b10036 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Rise of the South African Reich Author/Creator Bunting, Brian; Segal, Ronald Publisher Penguin Books Date 1964 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Germany Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 960.5P398v.12cop.2 Rights By kind permission of Brian P. Bunting. Description "This book is an analysis of the drift towards Fascism of the white government of the South African Republic.