Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa: 1968

A survey of race relations in South Africa: 1968 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOO19690000.042.000 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org A survey of race relations in South Africa: 1968 Author/Creator Horrell, Muriel Publisher South African Institute of Race Relations, Johannesburg Date 1969-01 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, South Africa, Namibia Coverage (temporal) 1968 Source EG Malherbe Library Description A survey of race -

Military Conscription in South Africa, 1952-1972

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 1, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-1-29 46 PATRIOTIC DUTY OR RESENTED IMPOSITION? PUBLIC REACTIONS TO MILITARY CONSCRIPTION IN WHITE SOUTH AFRICA, 1952-1972 __________________________________ Graeme Callister Department of History, University of Stellenbosch1 Introduction It is widely known that from the introduction of the Defence Amendment Act of 1967 (Act no. 85 of 1967) until the fall of apartheid in 1994, South Africa had a system of universal national service for white males, and that the men conscripted into the South African Defence Force (SADF) under this system were engaged in conflicts in Namibia, Angola, and later in the townships of South Africa itself. What is widely ignored however, both in academia and in wider society, is that the South African military relied on conscripts, selected through a ballot system, to fill its ranks for some fifteen years before the introduction of universal service. This article intends to redress this scholastic imbalance. The period of universal military service coincides with the period that saw South Africa in the world’s spotlight, when defeating apartheid was the great crusade in which capitalist and communist alike could engage. It is therefore not surprising that the military of that era has also been studied. Post-1967 universal national service in South Africa has received some attention from scholars, and is generally portrayed as a resented imposition at best. Resistance to conscription is widely covered, especially through the 1980s when organisations such as the Conscientious Objectors Support Group (COSG, formed in 1980) and the End Conscription Campaign (ECC, formed in 1983) gave a more public ‘face’ to the anti-conscription movement.2 However, as can be seen from the relatively late 1 I would like to extend my gratitude to Professor Albert Grundlingh of the University of Stellenbosch for his comments and advice on the first draft of this article. -

BORN out of SORROW Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the Kwazulu-Natal Midlands Under Apartheid, 1948−1994 Volume One Compiled An

BORN OUT OF SORROW Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands under Apartheid, 1948−1994 Volume One Compiled and edited by Christopher Merrett Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation PIETERMARITZBURG 2021 Born out of Sorrow: Essays on Pietermaritzburg and the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands under Apartheid, 1948–1994. Volume One © Christopher Merrett Published in 2021 in Pietermaritzburg by the Trustees of the Natal Society Foundation under its imprint ‘Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation’. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without reference to the publishers, the Trustees of the Natal Society Foundation, Pietermaritzburg. Natal Society Foundation website: http://www.natalia.org.za/ ISBN 978-0-6398040-1-9 Proofreader: Catherine Munro Cartographer: Marise Bauer Indexer: Christopher Merrett Design and layout: Jo Marwick Body text: Times New Roman 11pt Front and footnotes: Times New Roman 9pt Front cover: M Design Printed by CPW Printers, Pietermaritzburg CONTENTS List of illustrations List of maps and figures Abbreviations Preface Part One Chapter 1 From segregation to apartheid: Pietermaritzburg’s urban geography from 1948 1 Chapter 2 A small civil war: political conflict in the Pietermaritzburg region in the 1980s and early 1990s 39 Chapter 3 Emergency of the State: detention without trial in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands, 1986–1990 77 Chapter 4 Struggle in the workplace: trade unions and liberation in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands: part one From the 1890s to the 1980s 113 Chapter 5 Struggle in the workplace: trade unions and liberation in Pietermaritzburg and the Natal Midlands: part two Sarmcol and beyond 147 Chapter 6 Theatre of repression: political trials in Pietermaritzburg in the 1970s and 1980s 177 Part Two Chapter 7 Inkosi Mhlabunzima Joseph Maphumulo by Jill E. -

Welcome to KPMG Crescent

Jan Smuts Ave St Andrews M1 Off Ramp Winchester Rd Jan Smuts Off Ramp Welcome to KPMGM27 Crescent M1 North On Ramp De Villiers Graaff Motorway (M1) 85 Empire Road, Parktown St Andrews Rd Albany Rd GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.18548 | Longitude: 28.045142 85 Empire Road, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 B M1 North On Ramp Directions: From Sandton/Pretoria M1 South Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg On Ramp Jan Smuts / Take Empire off ramp, at the robot turn left to the KPMG main St Andrews gate. (NB – the Empire entrance is temporarily closed). Continue Off Ramp to Jan Smuts Avenue, turn left and then first left into entrance on Empire Jan Smuts. M1 Off Ramp From South of JohannesburgWellington Rd /M2 Sky Bridge 4th Floor Take M1 (North) towards Sandton/Pretoria Take Exit 14A for Jan Smuts Avenue toward M27 and turn right M27 into Jan Smuts. At Empire Road turn right, at first traffic lights M1 South make a U-turn and travel back on Empire, and left into Jan Smuts On Ramp M17 Jan Smuts Ave Avenue, and first left into entrance. Empire Rd KPMG Entrance KPMG Entrance temporarily closed Off ramp On ramp T: +27 (0)11 647 7111 Private Bag 9, Jan Jan Smuts Ave F: +27 (0)11 647 8000 Parkview, 2122 E m p ire Rd Welcome to KPMG Wanooka Place St Andrews Rd, Parktown NORTH GPS Coordinates Latitude: -26.182416 | Longitude: 28.03816 St Andrews Rd, Parktown, Johannesburg, South Africa M1 St Andrews Off Ramp Jan Smuts Ave Directions: Winchester Rd From Sandton/Pretoria Take M1 (South) towards Johannesburg Take St Andrews off ramp, at the robot drive straight to the KPMG Jan Smuts main gate. -

The White Opposition Splits

12 THE WHITE OPPOSITION SPLITS STANLEY UYS Political Correspondent of the 'Sunday Times1 THE annual congress of the official South African Parliamentary Opposition or United Party in August last year, on the eve of the Provincial Elections, resulted in the resignation of almost a quarter of its Members of Parliament and the formation of a new white political party—the Progressives. Amidst the exhuma tions and excuses, analyses and adjustments that followed, two highly significant conclusions emerged—the official Parliamentary Opposition has swung substantially to the right, narrowing the already narrow gap between Government and United Party on the doctrines of race rule; and, for the first time in South African history, a substantial white Parliamentary Party with wide, if not dominant, electoral support in many urban areas, had come into existence specifically in order to propagate a more liberal policy in race relations. The origin of the Progressive break must be sought in the right-wing ''rethinking" resulting from the total failure of the United Party to avoid a steady electoral decline during the n years in which it has been in Opposition. In 1948, the Nationalist Party came to power with a majority of fewer than half-a-dozen M.P.s. Today, it has two-thirds of the House of Assembly, partly due to the completely one-sided character of the electoral system (particularly delimitation methods) and partly to the growing numerical superiority of the Afrikaner. It did not take the United Party long to evolve the view that there was no profit in battering its head against a stone wall, and that the only chance of success lay in winning over "moderate'' Nationalist voters. -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

A1132-Ba2-002-Jpeg.Pdf

- ■ m m m Two-voice plan bristles with contradictions N the first two articles I either individuals or racial be shared with all those non- wrote that United Party groups, and apart from a brief Europeans who have shown that I reference to what was clearly they have the capacity to take speakers often contradict joint responsibility with us for each other and even them meant as safeguards between the future development of selves in their statements on the two White sections and South Afriea.” ("Weekblad,” which was made in the "Ordered 1 7 . 3 . 6 1 . ) COUNTS v> their race federation plan. In the tame speech the Advance” pamphlet issued by OLITICAL parties, more | Those contradictions are no leader of the United Party doubt an indication that the Sir De Villiers Graaff on Oc than most other organisa- S tober 25, 1960, I could find little went on to say: "W e want j P! tions of people, reflect the whole plan was rather hur them (the Africans) to be re W , i riedly conceived and pre or no reference to constitutional , quality of human material safeguards in United Party presented by eight European \ j they embody. In other words maturely horn and that the members, elected by those I good people tend to make for f leaders of the United Party policy. Natives who have shown them- ■ | a good party, indifferent j have not even considered Nevertheless the United selves to be responsible citi people for an indifferent party, ï certain vital aspects of their Party has as its main policy plank, the safeguarding of zens of our country." But ham and bad people for a bad party. -

![The Preview Edition [PDF] Here](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6005/the-preview-edition-pdf-here-1066005.webp)

The Preview Edition [PDF] Here

Humanistic Judaism Magazine Helen Suzman 2021–2022 Humanistic Jewish Role Model Diagnosis: Casteism by Rabbi Jeffrey Falick Challenging the Phrase "Judeo-Christian Values" by Lincoln Dow A Woman of Valor for the Ages by Marilyn Boxer Community News and much more Spring 2021 Table of Contents From the Editor Tributes, Board of Directors, p. 3 Communities p. 21–22 Humanism Can Lead to the Future Acceptance of Tolerance and Human Unity p. 4, 20 Contributors I Marilyn J. Boxer is secretary and program co-chair at by Professor Mike Whitty Kol Hadash in Berkeley, California. She is also professor emerita of history and former vice-president/provost at San Helen Suzman Francisco State University. p. 5–6 I Lincoln Dow is the Community Organizer of Jews for a Secular Democracy, a pluralistic initiative of the Society for A Woman of Valor for the Ages Humanistic Judaism. He studies politics and public policy by Marilyn Boxer at New York University. I Rachel Dreyfus is the Partnership & Events Coordinator “I Was Just Doing My Job” for the Connecticut CHJ. I Jeffrey Falick is the Rabbi of The Birmingham Temple, p. 7–8 Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. Interviews with Paul Suzman and Frances Suzman Jowell I K. Healan Gaston is Lecturer on American Religious by Dan Pine History and Ethics at Harvard Divinity School and the author of Imagining Judeo-Christian America: Religion, Imagining Judeo-Christian America Secularism, and the Redefinition of Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 2019). She is currently completing p. 9, 18 Beyond Prophetic Pluralism: Reinhold and H. Richard Book Excerpt by K. -

Colin Eglin, the Progressive Federal Party and the Leadership of the Official Parliamentary Opposition, 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987

Journal for Contemporary History 40(1) / Joernaal vir Eietydse Geskiedenis 40(1): 1‑22 © UV/UFS • ISSN 0285‑2422 “ONE OF THE ARCHITECTS OF OUR DEMOCRACY”: COLIN EGLIN, THE PROGRESSIVE FEDERAL PARTY AND THE LEADERSHIP OF THE OFFICIAL PARLIAMENTARY OPPOSITION, 1977‑1979 AND 1986‑1987 FA Mouton1 Abstract The political career of Colin Eglin, leader of the Progressive Federal Party (PFP) and the official parliamentary opposition between 1977‑1979 and 1986‑1987, is proof that personality matters in politics and can make a difference. Without his driving will and dogged commitment to the principles of liberalism, especially his willingness to fight on when all seemed lost for liberalism in the apartheid state, the Progressive Party would have floundered. He led the Progressives out of the political wilderness in 1974, turned the PFP into the official opposition in 1977, and picked up the pieces after Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s dramatic resignation as party leader in February 1986. As leader of the parliamentary opposition, despite the hounding of the National Party, he kept liberal democratic values alive, especially the ideal of incremental political change. Nelson Mandela described him as, “one of the architects of our democracy”. Keywords: Colin Eglin; Progressive Party; Progressive Federal Party; liberalism; apartheid; National Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leader of the official parliamentary opposition. Sleutelwoorde: Colin Eglin; Progressiewe Party; Progressiewe Federale Party; liberalisme; apartheid; Nasionale Party; Frederik van Zyl Slabbert; leier van die amptelike parlementêre opposisie. 1. INTRODUCTION The National Party (NP) dominated parliamentary politics in the apartheid state as it convinced the majority of the white electorate that apartheid, despite the destruction of the rule of law, was a just and moral policy – a final solution for the racial situation in the country. -

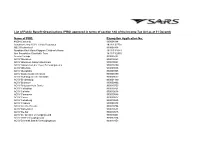

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Johannes De Villiers Graaff1 Johannes De Villiers Graaff, Known

Johannes de Villiers Graaff1 Johannes de Villiers Graaff, known more simply as Jan Graaff, shared with that other great son of the Boland, JM Coetzee, the somewhat terrifying power of silent authority which comes from that mixture of brilliant intelligence combined with surprising shyness. Small talk was not part of his character and he could be a highly intimidating presence to those who met him. But for those, family and friends, who got to know him, he was a warm and wonderful human being and could be a great storyteller. Once, when he was trapped in a window seat on a flight to London and I was in the aisle, I was able to ask him a lot of questions which he could not escape, so I learnt a good deal. Why, for example, was he (whom we lesser mortals all knew to be the greatest economist that South Africa had produced and who loved his discipline) not willing to join the faculty of one of our universities to teach students? His answer was that he had tried teaching in Cambridge and in Harvard but had decided that the internecine departmental politics that he encountered was so offensive that he resolved never to spend his working life in such an environment. And so, Paul Samuelson from MIT, writing in the pages of the Economic Journal in September 1958 when Jannie Graaff was only 30 but had already decided to leave academia, lamented that “economics has lost so able a mind”. Joan Robinson said that he was the brightest PhD student that Cambridge had ever had. -

The South African Developmental State of the 1940S1

Article A ghost from the past: the South African developmental state of the 1940s1 Bill Freund [email protected] Abstract Bill Freund offers an account of the development of South African capitalism through the lens of the ‘development state’ model. This model is a label used in the variety of capitalism literature to describe state-business relations in some Asian economies, including Japan, in the post war era. Though focusing on the 1940s, Freund examines the early signs of such a model in the period immediately after the South African (Boer) war, associated with Alfred, Lord Milner, which has come to be known as the ‘reconstruction’ period. While conventional wisdom associates the policy initiatives of the 1924 Pact government around industrial and labour policy to the need to accommodate ‘poor whites’, Freund, following Christie, Clark and others, also argues that these and related policies also incorporated strong elements of industrialization (arguably though cautiously), even ‘developmentalism’ 1. The Developmental State In recent years, with eyes alerted to the so-called Asian industrialisation model, there has emerged an important literature on the developmental state with Johnson, Amsden and Chang amongst the most frequently cited studies (Johnson 1982, Amsden 1989, Chang 1994). Meredith Woo-Cumings provides a collection which stretches the subject to consider, for instance, dirigiste France and which also gives convenient definitional strength to the concept (Woo-Cumings1999). ‘The common thread linking these arguments is that a developmental state is not an imperious element lording it over society but a partner with the business sector in an historical compact of industrial transformation’ (1999:4).