Emile Borel's Difficult Days in 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert De Montessus De Ballore's 1902 Theorem on Algebraic

Robert de Montessus de Ballore’s 1902 theorem on algebraic continued fractions : genesis and circulation Hervé Le Ferrand ∗ October 31, 2018 Abstract Robert de Montessus de Ballore proved in 1902 his famous theorem on the convergence of Padé approximants of meromorphic functions. In this paper, we will first describe the genesis of the theorem, then investigate its circulation. A number of letters addressed to Robert de Montessus by different mathematicians will be quoted to help determining the scientific context and the steps that led to the result. In particular, excerpts of the correspondence with Henri Padé in the years 1901-1902 played a leading role. The large number of authors who mentioned the theorem soon after its derivation, for instance Nörlund and Perron among others, indicates a fast circulation due to factors that will be thoroughly explained. Key words Robert de Montessus, circulation of a theorem, algebraic continued fractions, Padé’s approximants. MSC : 01A55 ; 01A60 1 Introduction This paper aims to study the genesis and circulation of the theorem on convergence of algebraic continued fractions proven by the French mathematician Robert de Montessus de Ballore (1870-1937) in 1902. The main issue is the following : which factors played a role in the elaboration then the use of this new result ? Inspired by the study of Sturm’s theorem by Hourya Sinaceur [52], the scientific context of Robert de Montessus’ research will be described. Additionally, the correlation with the other topics on which he worked will be highlighted, -

The Mathematical Heritage of Henri Poincaré

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/pspum/039.1 THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE of HENRI POINCARE PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA IN PURE MATHEMATICS Volume 39, Part 1 THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE Of HENRI POINCARE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA IN PURE MATHEMATICS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 39 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON THE MATHEMATICAL HERITAGE OF HENRI POINCARfe HELD AT INDIANA UNIVERSITY BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA APRIL 7-10, 1980 EDITED BY FELIX E. BROWDER Prepared by the American Mathematical Society with partial support from National Science Foundation grant MCS 79-22916 1980 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01-XX, 14-XX, 22-XX, 30-XX, 32-XX, 34-XX, 35-XX, 47-XX, 53-XX, 55-XX, 57-XX, 58-XX, 70-XX, 76-XX, 83-XX. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Mathematical Heritage of Henri Poincare\ (Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics; v. 39, pt. 1— ) Bibliography: p. 1. Mathematics—Congresses. 2. Poincare', Henri, 1854—1912— Congresses. I. Browder, Felix E. II. Series: Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics; v. 39, pt. 1, etc. QA1.M4266 1983 510 83-2774 ISBN 0-8218-1442-7 (set) ISBN 0-8218-1449-4 (part 2) ISBN 0-8218-1448-6 (part 1) ISSN 0082-0717 COPYING AND REPRINTING. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit librar• ies acting for them are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy an article for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in re• views provided the customary acknowledgement of the source is given. -

Introduction: Some Historical Markers

Introduction: Some historical markers The aim of this introduction is threefold. First, to give a brief account of a paper of Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963) which is at the genesis of the theory of global proper- ties of surfaces of nonpositive Gaussian curvature. Then, to make a survey of several different notions of nonpositive curvature in metric spaces, each of which axioma- tizes in its own manner an analogue of the notion of nonpositive Gaussian curvature for surfaces and more generally of nonpositive sectional curvature for Riemannian manifolds. In particular, we mention important works by Menger, Busemann and Alexandrov in this domain. Finally, the aim of the introduction is also to review some of the connections between convexity theory and the theory of nonpositive curvature, which constitute the main theme that we develop in this book. The work of Hadamard on geodesics The theory of spaces of nonpositive curvature has a long and interesting history, and it is good to look at its sources. We start with a brief review of the pioneering paper by Hadamard, “Les surfaces à courbures opposées et leurs lignes géodésiques” [87]. This paper, which was written by the end of the nineteenth century (1898), can be considered as the foundational paper for the study of global properties of nonpositively curved spaces. Before that paper, Hadamard had written a paper, titled “Sur certaines propriétés des trajectoires en dynamique” (1893) [84], for which he had received the Borodin prize of the Académie des Sciences.1 The prize was given for a contest whose topic was “To improve in an important point the theory of geodesic lines”. -

![Arxiv:Math/0611322V1 [Math.DS] 10 Nov 2006 Sisfcsalte Rmhdudt Os,Witnbtent Between Int Written Subject the Morse, Turn to to Intention Hedlund His Explicit](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2205/arxiv-math-0611322v1-math-ds-10-nov-2006-sisfcsalte-rmhdudt-os-witnbtent-between-int-written-subject-the-morse-turn-to-to-intention-hedlund-his-explicit-1522205.webp)

Arxiv:Math/0611322V1 [Math.DS] 10 Nov 2006 Sisfcsalte Rmhdudt Os,Witnbtent Between Int Written Subject the Morse, Turn to to Intention Hedlund His Explicit

ON THE GENESIS OF SYMBOLIC DYNAMICS AS WE KNOW IT ETHAN M. COVEN AND ZBIGNIEW H. NITECKI Abstract. We trace the beginning of symbolic dynamics—the study of the shift dynamical system—as it arose from the use of coding to study recurrence and transitivity of geodesics. It is our assertion that neither Hadamard’s 1898 paper, nor the Morse-Hedlund papers of 1938 and 1940, which are normally cited as the first instances of symbolic dynamics, truly present the abstract point of view associated with the subject today. Based in part on the evidence of a 1941 letter from Hedlund to Morse, we place the beginning of symbolic dynamics in a paper published by Hedlund in 1944. Symbolic dynamics, in the modern view [LM95, Kit98], is the dynamical study of the shift automorphism on the space of bi-infinite sequences of symbols, or its restriction to closed invariant subsets. In this note, we attempt to trace the begin- nings of this viewpoint. While various schemes for symbolic coding of geometric and dynamic phenomena have been around at least since Hadamard (or Gauss: see [KU05]), and the two papers by Morse and Hedlund entitled “Symbolic dynamics” [MH38, MH40] are often cited as the beginnings of the subject, it is our view that the specific, abstract version of symbolic dynamics familiar to us today really began with a paper,“Sturmian minimal sets” [Hed44], published by Hedlund a few years later. The outlines of the story are familiar, and involve the study of geodesic flows on surfaces, specifically their recurrence and transitivity properties; this note takes as its focus a letter from Hedlund to Morse, written between their joint papers and Hedlund’s, in which his intention to turn the subject into a part of topology is explicit.1 This letter is reproduced on page 6. -

The Exact Sciences Michel Paty

The Exact Sciences Michel Paty To cite this version: Michel Paty. The Exact Sciences. Kritzman, Lawrence. The Columbia History of Twentieth Century French Thought, Columbia University Press, New York, p. 205-212, 2006. halshs-00182767 HAL Id: halshs-00182767 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00182767 Submitted on 27 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 The Exact Sciences (Translated from french by Malcolm DeBevoise), in Kritzman, Lawrence (eds.), The Columbia History of Twentieth Century French Thought, Columbia University Press, New York, 2006, p. 205-212. The Exact Sciences Michel Paty Three periods may be distinguished in the development of scientific research and teaching in France during the twentieth century: the years prior to 1914; the interwar period; and the balance of the century, from 1945. Despite the very different circumstances that prevailed during these periods, a certain structural continuity has persisted until the present day and given the development of the exact sciences in France its distinctive character. The current system of schools and universitiespublic, secular, free, and open to all on the basis of meritwas devised by the Third Republic as a means of satisfying the fundamental condition of a modern democracy: the education of its citizens and the training of elites. -

Jacques Hadamard in China by Wenlin Li*

Jacques Hadamard in China by Wenlin Li* In the nineteen-thirties, academic exchanges with de Lyon, 1920) and King-Lai Hiong ( , Université Western countries were becoming increasingly active de Montpellier, 1920). From 1920 onwards, the ma- in China. It was a period in the development of mathe- terial conditions for overseas Chinese students im- matics in modern China of which a significant feature proved, and there appeared special institutes such was the invitation of leading mathematicians from as l’Institut Franco-Chinois de Lyon, which became the United States and Europe to lecture in China. a center for Chinese students and produced, from Among these was Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963) 1920 to 1930, the first batch of Chinese doctorates of France. In this article, Hadamard’s visit, its back- in mathematics in France: Chou-Chi Yuan ( , ground, and its influence are discussed on the basis 1927), Tsin-Yi Tchao ( , 1928), Wui-Kwok Fan of existing sources. ( , Université de Paris, 1929), and Tsyun-Hyen Liou ( , 1930); as well as master degrees in Background of Sino-French mathematics: Yanxuan He ( , 1924), Jinmin Chen ( , 1925) and Cuimin Shan ( , 1926). Mathematical Exchanges All the students mentioned above returned to Mathematical exchanges between France and China after finishing their studies in France and China could be traced back to the late 19th cen- played an active role as forerunners in the develop- tury. In 1887, two students, Tseng-Fong Ling ( ) ment of modern mathematics in China. Most of them and Cheou-Tchen Tcheng ( ) were sent by the had led the newly established departments of math- Fuzhou Naval College to l’École Normale Supérieur in ematics in Chinese universities, among these being Paris where they eventually obtained their bachelor Tsinghua University, Peking Normal University, Cen- degrees in science in 1890. -

Dissertation Discrete-Time Topological Dynamics

DISSERTATION DISCRETE-TIME TOPOLOGICAL DYNAMICS, COMPLEX HADAMARD MATRICES, AND OBLIQUE-INCIDENCE ION BOMBARDMENT Submitted by Francis Charles Motta Department of Mathematics In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2014 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Patrick D. Shipman Gerhard Dangelmayr Chris Peterson R. Mark Bradley Copyright by Francis Charles Motta 2014 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT DISCRETE-TIME TOPOLOGICAL DYNAMICS, COMPLEX HADAMARD MATRICES, AND OBLIQUE-INCIDENCE ION BOMBARDMENT The topics covered in this dissertation are not unified under a single mathematical dis- cipline. However, the questions posed and the partial solutions to problems of interest were heavily influenced by ideas from dynamical systems, mathematical experimentation, and simulation. Thus, the chapters in this document are unified by a common flavor which bridges several mathematical and scientific disciplines. The first chapter introduces a new notion of orbit density applicable to discrete-time dynamical systems on a topological phase space, called the linear limit density of an orbit. For a fixed discrete-time dynamical system, Φ(x): M ! M defined on a bounded metric space, : t we introduce a function E : fγx : x 2 Mg ! R[f1g on the orbits of Φ, γx = fΦ (x): t 2 Ng, and interpret E(γx) as a measure of the orbit's approach to density; the so-called linear limit density (LLD) of an orbit. We first study the family of dynamical systems Rθ : [0; 1) ! [0; 1) (θ 2 (0; 1)) defined by Rθ(x) = (x + θ) mod 1. Utilizing a formula derived from the Three- t Distance theorem, we compute the exact value of E(fRφ(x): t 2 Ng; x 2 [0; 1)), where p t φ = 5 − 1 =2. -

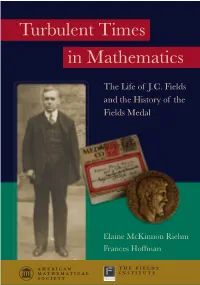

Turbulent Times in Mathematics

Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal Elaine McKinnon Riehm Frances Hoffman AMERICAN THE FIELDS MATHEMATICAL INSTITUTE SOCIETY Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY THE FIELDS INSTITUTE Original prototype of the Fields Medal, cast in bronze, mailed to J. L. Synge at the University of Toronto in 1933. http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/mbk/080 Turbulent Times in Mathematics The Life of J.C. Fields and the History of the Fields Medal Elaine McKinnon Riehm Frances Hoffman AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY THE FIELDS INSTITUTE 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01–XX, 01A05, 01A55, 01A60, 01A70, 01A73, 01A99, 97–02, 97A30, 97A80, 97A40. Cover photo of J.C. Fields standing outside Convocation Hall — at the time of the IMC, Toronto, 1924 — courtesy of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. Cover and frontispiece photo of the Fields Medal and its original box courtesy of Andrea Yeomans. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/mbk-80 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Riehm, Elaine McKinnon, 1936– Turbulent times in mathematics : the life of J. C. Fields and the history of the Fields Medal / Elaine McKinnon Riehm, Frances Hoffman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8218-6914-7 (alk. paper) 1. Fields, John Charles, 1863–1932. 2. Mathematicians—Canada—Biography. 3. Fields Prizes. I. Hoffman, Frances, 1944– II. Title. QA29.F54 R53 2011 510.92—dc23 [B] 2011021684 Copying and reprinting. -

Jacques Hadamard English Version

JACQUES HADAMARD (December 8, 1865 – October 17, 1963) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK, Germany Mathematicians who deal intensively with prime numbers live long ... You could agree with this rather light-hearted saying when you consider the ages of CHARLES DE LA VALLÉE POUSSIN and JACQUES SALOMON HADAMARD – the former lived to be 95 years old, the latter 97 years. These two mathematicians shared a very special accomplishment: independently in 1896, they proved the so-called prime number theorem. π x)( This states that the quotient converges to one, where π x)( xx )ln(/ denotes the number of prime numbers which are at most equal to x. JACQUES SALOMON HADAMARD was the first child of AMÉDÉE HADAMARD and CLAIRE MARIE JEANNE PICARD. The father taught history, grammar and classical literature at the Lycée Imperial in Versailles; the mother gave private piano lessons at home. In 1869 the young family moved to Paris, where AMÉDÉE HADAMARD took a job at the Lycée Charlemagne – just a few months before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war. As the Prussian troops were about to lay siege to Paris, the newly-born second child of the HADAMARDs (a daughter) died. A great famine broke out in the capital. After the armistice in January 1871, a humiliating peace treaty followed in May. In Paris, civil war-like conditions occurred, in which the HADAMARD family's house was destroyed. A second daughter also died; she was not even three years old. From 1874, JACQUES attended the Lycée, where his father worked as a teacher, with excellent performances – except in arithmetic. -

Ufev License Or Copyright Restrictions May Apply to Redistribution; See JACQUES HADAMARD (1865-1963)

Ufev License or copyright restrictions may apply to redistribution; see https://www.ams.org/journal-terms-of-use License or copyright restrictions may apply to redistribution; see https://www.ams.org/journal-terms-of-use JACQUES HADAMARD (1865-1963) SZOLEM MANDELBROJT AND LAURENT SCHWARTZ Jacques Hadamard, whose mathematical work extends over almost three quarters of a century, passed away on October 17, 1963 at the age of nearly 98 years: he was born on December 8, 1865. Only a very few mathematicians of the last hundred years left so rich a heritage in so many fields as Hadamard did. As a matter of fact, few of the fundamental fields of mathematics were not deeply influenced by his genius. Many of the most important ones owe to Hadamard their intimate nature and ways of research, some of them their existence. In introducing Hadamard to the London Mathematical Society in 1944, where he was asked to speak about his most striking discoveries, Hardy called him, I remember, the "living legend" in mathematics. I will have to limit myself to only the most important ideas and results spread through this legendary work. The first important papers of Hadamard dealt with analytic func tions, or, more precisely, with the study of the nature of an analytic function defined by its Taylor series. Weierstrass, and Méray in France, on defining rigorously the meaning of analytic continuation of such a series, took that series as the starting point of the definition of an analytic function. But this is merely an existence and unique ness theorem, and the problem of actually indicating the properties of the function so defined, starting from the properties of the coeffi cients, remained almost untouched. -

On the Number of Hadamard Matrices Via Anti-Concentration

On the number of Hadamard matrices via anti-concentration Asaf Ferber ∗ Vishesh Jainy Yufei Zhao z Abstract Many problems in combinatorial linear algebra require upper bounds on the number of so- lutions to an underdetermined system of linear equations Ax = b, where the coordinates of the vector x are restricted to take values in some small subset (e.g. {±1g) of the underlying field. The classical ways of bounding this quantity are to use either a rank bound observation due to Odlyzko or a vector anti-concentration inequality due to Halász. The former gives a stronger conclusion except when the number of equations is significantly smaller than the number of variables; even in such situations, the hypotheses of Halász’s inequality are quite hard to verify in practice. In this paper, using a novel approach to the anti-concentration problem for vector sums, we obtain new Halász-type inequalities which beat the Odlyzko bound even in settings where the number of equations is comparable to the number of variables. In addition to being stronger, our inequalities have hypotheses which are considerably easier to verify. We present two applications of our inequalities to combinatorial (random) matrix theory: (i) we obtain the first non-trivial upper bound on the number of n × n Hadamard matrices, and (ii) we improve a recent bound of Deneanu and Vu on the probability of normality of a random {±1g matrix. 1 Introduction 1.1 The number of Hadamard matrices A square matrix H of order n whose entries are {±1g is called a Hadamard matrix of order n if its T rows are pairwise orthogonal i.e. -

Tales of Our Forefathers

Introduction Family Matters Educational Follies Tales of Our Forefathers Underappreciated Mathematics Death of a Barry Simon Mathematician Mathematics and Theoretical Physics California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA, U.S.A. but it is a talk for mathematicians. It is dedicated to the notion that it would be good that our students realize that while Hahn–Banach refers to two mathematicians, Mittag-Leffler refers to one. Introduction This is not a mathematics talk Introduction Family Matters Educational Follies Underappreciated Mathematics Death of a Mathematician It is dedicated to the notion that it would be good that our students realize that while Hahn–Banach refers to two mathematicians, Mittag-Leffler refers to one. Introduction This is not a mathematics talk but it is a talk for mathematicians. Introduction Family Matters Educational Follies Underappreciated Mathematics Death of a Mathematician Mittag-Leffler refers to one. Introduction This is not a mathematics talk but it is a talk for mathematicians. It is dedicated to the notion that it would Introduction be good that our students realize that while Hahn–Banach Family Matters refers to two mathematicians, Educational Follies Underappreciated Mathematics Death of a Mathematician Introduction This is not a mathematics talk but it is a talk for mathematicians. It is dedicated to the notion that it would Introduction be good that our students realize that while Hahn–Banach Family Matters refers to two mathematicians, Educational Follies Underappreciated Mathematics Death of a Mathematician Mittag-Leffler refers to one. In the early 1980s, Mike Reed visited the Courant Institute and, at tea, Peter Lax took him over to a student who Lax knew was a big fan of Reed–Simon.