SEASONS in the SUN Version for BRITA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

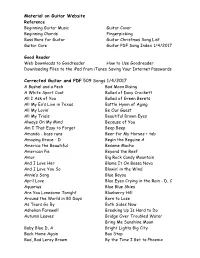

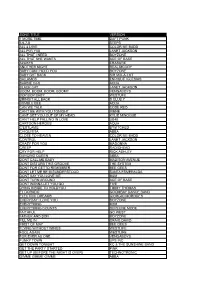

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission Home Page

^^rv Pennsylvania December 1985/80V ANGLER The Keystone State's Official Fishing Magazine W: SStflifc.i-i. Yx«sjt*sirf, ..»** <*.«» »«i»i-*W5w<^i. V fc/^-S*. •^*WH* %**•* *• ^M " *I|P f^SB The year 1985 will go down in the books as another serious drought year, albeit the greenest in memory. There was good precipitation in the springtime, but by early summer we began to see the deficits in precipitation. This came on top of a general lack of snow cover, and water tables began to sink. There was enough rain to keep most lawns green, and even the farmers weren't hurting too much because there was enough precipitation to go root-deep. Hurricane Gloria, with its rains covering the eastern part of the Commonwealth, helped out some. Our salmon run in Lake Erie was impeded by warm water and the lack of water in the tributaries. The rains in early November wiped out the drought in the Delaware River Basin and even flooded parts of western Pennsylvania. And all the time, most weather broadcasters talked about the "threat" of rain; and again, this is their custom, believing that they are talking to an audience of people who only play golf, watch baseball games, and go on picnics. Across the Atlantic, the British Isles have had the wettest summer in over 100 years, with more than 150 inches of precipitation by the end of September. Even we would admit that's too much. At this point, however, it is difficult for anyone to enjoy living in this world unless he can accept its imperfection. -

Monster Hits Weekend! 31 October

MONSTER HITS WEEKEND! 31 OCTOBER - 1 NOVEMBER 2020 POP MUZIK M DEVIL GATE DRIVE SUZI QUATRO TIGHTER, TIGHTER ALIVE AND KICKING DRESSED FOR SUCCESS ROXETTE OUR LIPS ARE SEALED GO GO'S YOU'RE MOVING OUT TODAY CAROL BAYER SAGER TOO YOUNG TO BE MARRIED THE HOLLIES UPTOWN GIRL BILLY JOEL SOME GIRLS RACEY BEAST OF BURDEN BETTE MIDLER SUGAR BABY LOVE RUBETTES SHE'S THE ONE THE COCKROACHES TAKE IT EASY THE EAGLES SOMETHING'S WRONG WITH ME AUSTIN ROBERTS GOOSE BUMPS CHRISTIE ALLEN HOW DO YOU DO? MOUTH & McNEAL GOOD MORNING STARSHINE OLIVER TIRED OF TOWING THE LINE ROCKY BURNETTE COTTONFIELDS BEACH BOYS S-S-S-SINGLE BED FOX MOST PEOPLE I KNOW THINK THAT I'M CRAZY BILLY THORPE ETERNAL FLAME THE BANGLES HORROR MOVIE SKYHOOKS NINETEENTH NERVOUS BREAKDOWN THE ROLLING STONES GET USED TO IT ROGER VOUDOURIS ONE TIN SOLDIER COVEN ROCKABILLY REBEL MAJOR MATCHBOX LIFE IN A NORTHERN TOWN DREAM ACADEMY WARM RIDE GRAHAM BONNET THE LOVE GAME JOHN PAUL YOUNG KOKOMO BEACH BOYS STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES TOAST AND MARMALADE FOR TEA TIN TIN JANUARY PILOT DON'T PAY THE FERRYMAN CHRIS DeBURGH HIT THE ROAD JACK RAY CHARLES MY COO CA CHOO ALVIN STARDUST ESCAPE RUPERT HOLMES BANG BANG BA ROBERTSON WHENEVER YOU NEED SOMEBODY RICK ASTLEY YOU GOT IT ROY ORBISON LUCKY NUMBER LENE LOVICH DO IT AGAIN BEACH BOYS EYE OF THE TIGER SURVIVOR LITTLE RED ROOSTER THE ROLLING STONES SEASONS IN THE SUN TERRY JACKS I GOT YOU SPLIT ENZ EAGLE ROCK DADDY COOL LIFE SHERBET COMPUTER GAMES MI SEX SHE'S SO FINE EASYBEATS KING OF WISHFUL THINKING GO WEST WHEN I'M DEAD AND GONE McGUINNESS FLINT HAIR -

Artist : Nana Mouskouri 1958 EP & Singles Greece Genre : Pop Year

Artist : Nana Mouskouri 1958 EP & singles Greece Genre : Pop Year : 1958 Tracks : 10 Playtime : 00:31:02 01. Hartino To Fengaraki (The Paper Moon) (03:25) 02. Mazi Me Sena (Together) (02:52) 03. Ilissos (03:22) 04. Ela Pare Mou Ti Lipi (Take My Sorrow Away) (03:14) 05. I mana mou me dernei (02:42) 06. Annista mou Annoula mou (03:08) 07. Pame Mia Volta Sto Fengari (Walking On The Moon) (03:21) 08. Kanella Kaneloritsa (Kato sto Yialo) (03:06) 09. Eri Erini (02:53) 10. Fascination (02:55) EP 8001 Universal cover Greece 1958 01. Hartino To Fengaraki (The Paper Moon) (03:25) Fidelity EP 8001 Made in Greece 1958 Performer : Nana Mouskouri Music : Manos Hadjidakis Lyrics : Nikos Gatsos Tha feri i thalasa poulia Tha san ola alithina An me pisteves ligaki Ki astra hrysa tageri Dihos ti diki sou agapi Tha san ola alithina Na sou haidevoun ta malia Grigora perna o keros Hartino to fengaraki Na sou filoun to cheri Dihos ti diki sou agapi Pseftiki i akrogialia Hartino to fengaraki Ine o kosmos pio mikros An me pisteves ligaki Pseftiki i akrogialia Hartino to fengaraki Tha san ola alithina An me pisteves ligaki Pseftiki i akrogialia -------------------------- 1 02. Mazi Me Sena (Together) (02:52) Fidelity EP 8001 Made in Greece 1958 Fidelity 7001 Made in Greece 1958 Performer : Nana Mouskouri Music : Manos Hadjidakis Lyrics : Nikos Gatsos Mazi me sena Ki ego ime mono mia fotia Mazi me sena Ine i zoi mou enas kipos me Thelo na zviso sti dikia sou Tha taxidepso os tin akri poulia agkalia. -

Top500 Final

1. MICHAEL JACKSON Billie Jean 2. EAGLES Hotel California 3. BON JOVI Livin’ On A Prayer 4. ROLLING STONES Satisfaction 5. POLICE Every Breath You Take 6. ARETHA FRANKIN Respect 7. JOURNEY Don’t Stop Believin’ 8. BEATLES Hey Jude 9. GUESS WHO American Woman 10. QUEEN Bohemian Rhapsody 11. MARVIN GAYE I Heard It Through The Grapevine 12. JOAN JETT I Love Rock And Roll 13. BEE GEES Night Fever 14. BEACH BOYS Good Vibrations 15. BLONDIE Call Me 16. FOUR SEASONS December 1963 (Oh, What A Night) 17. BRYAN ADAMS Summer Of 69 18. SURVIVOR Eye Of The Tiger 19. LED ZEPPELIN Stairway To Heaven 20. ROY ORBISON Pretty Woman 21. OLIVIA NEWTON JOHN Physical 22. B.T.O. Takin’ Care Of Business 23. NEIL DIAMOND Sweet Caroline 24. DON McLEAN American Pie 25. TOM COCHRANE Life Is A Highway 26. BOSTON More Than A Feeling 27. MICHAEL JACKSON Rock With You 28. ROD STEWART Maggie May 29. VAN HALEN Jump 30. ELTON JOHN/ KIKI DEE Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 31. FOUR SEASONS Big Girls Don’t Cry 32. FLEETWOOD MAC Dreams 33. FIFTH DIMENSION Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In 34. HALL AND OATES Maneater 35. NEIL YOUNG Heart Of Gold 36. PRINCE When Doves Cry 37. EAGLES Lyin’ Eyes 38. ARCHIES Sugar, Sugar 39. THE KNACK My Sharona 40. BEE GEES Stayin’ Alive 41. BOB DYLAN Like A Rolling Stone 42. AMERICA Sister Golden Hair 43. ALANNAH MYLES Black Velvet 44. FRANKI VALLI Grease 45. PAT BENATAR Hit Me With Your Best Shot 46. EMOTIONS Best Of My Love 47. -

Business Proposal

BUSINESS PARTNERSHIP PROPOSAL “FIRST TIME IN INDIA” New Delhi, INDIA 21st - 23rd AUGUST, 2020 ORGANISED BY NEXODE MEDIA PVT. LTD. ABOUT GLOBAL YOUTH LEADERS MODEL UNITED NATIONS Global Youth Leaders MUN (GYLMUN) will be held on August 21-23, 2020 in New Delhi, India. GYLMUN is aimed to provide a platform for youth to learn about diplomacy, critical thinking, public speaking and the United Nations Conference. The ultimate goal of GYLMUN is to encourage the youth to be aware of the international issues, understand and try to form a possible solution to solve particular issues related to the 17 Global Goals. The youth will feel the ambience of being representatives of their assigned countries and experience how the United Nations Conference executes their ideas and plans. It is the best platform where they can improve their soft skills and knowledge and expand their network. ABOUT GLOBAL YOUTH LEADERS MODEL UNITED NATIONS As an important part of the world, youth have responsibilities and rights to contribute to the realization of Global Goals as a key to transform our world into a better place to live in. As a youth capacity development platform, Nexode Media has consistently put effort to arrange some programs that are relevant to youth in today's need and for the better future of the world. The organization is eager to create a platform, form an alliance between young leaders, which will accommodate ideas from youth spread all over the countries through the programs. Youth leaders will get more perspectives from the world, thus, they will enhance more understanding about related issues. -

Music's On-Line Future Shapes up by Juliana Koranteng Line Music Market

ave semen JANUARY 22, 2000 Music Volume 17, Issue 4 Media. £3.95 W-411` talk -C41:30 rya dio M&M chart toppers this week Music's on-line future shapes up by Juliana Koranteng line music market. Also, the deal could untoward about one of the world's Eurochart Hot 100 Singles catapult Warner Music Group (WMG), media groups merging with the world's EIFFEL 65 LONDON - Last week's unexpectedTime Warner's music division, intomost successful on-line group," notes Move You Body takeover of Time Warner by on-linefrontrunner positioninthedigital New York -based Aram Sinnreich, ana- (Bliss Co.) giant America Online (AOL) not only delivery race among the five majors. lyst at Jupiter Communications. "It will European Top 100 Albums confirms the much predicted conver- The AOL/Time Warner merger help speed the adoption of on-line music immediatelyovershadowedother by consumers." Sinnreich adds that "It CELINE DION gence of old and new media, but also acknowledges the Internet as the importantdownloadable could even make or break a All The Way..A Decade of Song biggest influence on the future music deals announced band, which has not been (Epic/Columbia) growth of global music sales. A M ER ICA shortly beforehand byTI\IF. ARNFR done so far on the Internet. European Radio Top 50 According to analysts, Universal Music But AOL has the ability to CELINE DION shareholderandregulatory Group(UMG) andSony do so. As a well-known global brand, AOL's ambitions will be far-reaching. That's The Way It'Is approval of AOL/Time Warn- Music Entertainment (SME). -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

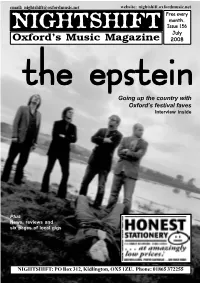

Issue 156.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 156 July Oxford’s Music Magazine 2008 thethethe epsteinepsteinepstein Going up the country with Oxford’s festival faves Interview inside Plus News, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net LOCAL PHOTOGRAPHER MARC WEST has an exhibition of his music photos at the Lolapaloza Gallery on Blue Boar Street from Monday 30th June through to Thursday 31st July. Marc, whose exhibition is entitled First 3, No Flash, regularly contributes live photos to Nightshift as well as conducting band interviews for BBC Rado Oxford’s Introducing music show. Lolapaloza is open from 10am through to 5.30pm. A LOCAL POP LEGENDS THE special evening viewing, on Friday 4th July, CANDYSKINS are set to reform again for from 5.30-8pm, features a live set from a one-off Music For Life gig in aid of Tristan & The Troubadours. Cancer Research at the Academy on Friday 8th August. The band, who last played SUNNYVALE NOISE SUB-ELEMENT together at the Zodiac’s closing down party release a limited edition album of live last year, will be joined by fellow Britpop tracks and remixes this month. ‘More stars Dodgy as well as Frank Turner and A Than 20%’ is available from the band’s Silent Film. The benefit gig is being website and comes in a hand-doodled and organised by Dave Holt, who managed numbered mailer box and features remixes Unbelievable Truth and promoted early by the likes of Boywithatoy, Eduard shows by Radiohead and Supergrass, who Soundingblock, Space Heroes of the has been treated for cancer this year. -

Jukebox Decades – 100 Hits Ultimate Soul

JUKEBOX DECADES – 100 HITS ULTIMATE SOUL Disc One - Title Artist Disc Two - Title Artist 01 Ain’t No Sunshine Bill Withers 01 Be My Baby The Ronettes 02 How ‘Bout Us Champaign 02 Captain Of Your Ship Reparata 03 Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 03 Band Of Gold Freda Payne 04 Me & Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 04 Midnight Train To Georgia Gladys Knight 05 If You Don’t Know Me Harold Melvin 05 Piece of My Heart Erma Franklin 06 Turn Off The Lights Teddy Pendergrass 06 Woman In Love The Three Degrees 07 A Little Bit Of Something Little Richard 07 I Need Your Love So Desperately Peaches 08 Tears On My Pillow Johnny Nash 08 I’ll Never Love This Way Again D Warwick 09 Cause You’re Mine Vibrations 09 Do What You Gotta Do Nina Simone 10 So Amazing Luther Vandross 10 Mockingbird Aretha Franklin 11 You’re More Than A Number The Drifters 11 That’s What Friends Are For D Williams 12 Hold Back The Night The Tramps 12 All My Lovin’ Cheryl Lynn 13 Let Love Come Between Us James 13 From His Woman To You Barbara Mason 14 After The Love Has Gone Earth Wind & Fire 14 Personally Jackie Moore 15 Mind Blowing Decisions Heatwave 15 Every Night Phoebe Snow 16 Brandy The O’ Jays 16 Saturday Love Cherrelle 17 Just Be Good To Me The S.O.S Band 17 I Need You Pointer Sisters 18 Ready Or Not Here I The Delfonics 18 Are You Lonely For Me Freddie Scott 19 Home Is Where The Heart Is B Womack 19 People The Tymes 20 Birth The Peddlers 20 Don’t Walk Away General Johnson Disc Three - Title Artist Disc Four - Title Artist 01 Till Tomorrow Marvin Gaye 01 Lean On Me Bill Withers 02 Here -

Off-Beats and Cross Streets: a Collection of Writing About Music, Relationships, and New York City

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Stonecoast MFA Student Scholarship 2020 Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City Tyler Scott Margid University of Southern Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast Recommended Citation Margid, Tyler Scott, "Off-Beats and Cross Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City" (2020). Stonecoast MFA. 135. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast/135 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stonecoast MFA by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Off-Beats and Cross-Streets: A Collection of Writing about Music, Relationships, and New York City A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUTREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE, STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITINC BY Tyler Scott Margid 20t9 THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING November 20,2019 We hereby recommend that the thesis of Tyler Margid entitled OffÙeats and Cross- Streets be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Advisor Florio -'1 4rl:ri'{" ¡ 'l¡ ¡-tÁ+ -- Reader Debra Marquart Director J Accepted ¿/k Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Adam-Max Tuchinsky At¡stract Through a series of concert reviews, album reviews, and personal essays, this thesis tracks a musical memoir about the transition from a childhood growing up in a sheltered Connecticut suburb to young adulthood working in New York City, discovering relationships and music scenes that shape the narrator's senss of identity as well the larger culture he f,rnds himself in. -

Brighton Ukulele Sundays 1St Songbook

Brighton Ukulele Sundays Songbook 2008 All Of Me 42 Puff The Magic Dragon 30 Baby Face 24 Ring Of Fire 6 Be My Baby 36 Rocket Man 19 Blowin’ In The Wind 4 Seasons In The Sun 3 Do Re Mi 5 Something 37 Eddystone Light 32 Somewhere Over The Rainbow 13 Everybody’s Talkin’ 41 Stairway To Heaven 10-11 Faith 2 Stand By Me 18 Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue 1 Summertime 17 Happy Days Theme 43 Sunday Morning 39 Heart of Gold 35 Suspicious Minds 14 House Of The Rising Sun 15 Tequila 32 I Can See Clearly Now 8 These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ 9 I Think We’re Alone Now 26 Ukulele Sundays Theme Song 25 25 I’m A Believer 12 Ukulele Time (In The Summertime) 27 King Of The Road 33 Under The Boardwalk 28 Mad World 23 Walk On The Wild Side 21 Maggie May 40 Who’s Sorry Now 38 Mr Blue Sky 34 Why Do Fools Fall In Love? 31 Nine To Five 20 YMCA 16 Panic 7 You Are My Sunshine 29 Peggy Sue 22 Brighton Ukulele Sundays – Songbook Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue by Sam Lewis, Young, and Henderson Verse 1: [C] Five foot two, [E7] eyes of blue But [A7] oh! what those five foot could do, Has [D7] anybody [G7] seen my [C] girl? [G7] Verse 2: [C] Turned up nose, [E7] turned down hose [A7] Flapper? Yes sir, one of those! Has [D7] anybody [G7] seen my [C] girl? Bridge: Now if you [E7] run into a five foot two, [A7] covered in fur, [D7] Diamond rings and all those things, [G7] Betcha' life [STOP] it isn't her! Verse 3: But, [C] could she love, [E7] could she woo? [A7] Could she, could she, could she coo? Has [D7] anybody [G7] seen my [C] girl? Has [D7] anybody [G7]seen my, [D7] anybody [G7] seen my, [D7] anybody [G7] seen my [C] girl? 07/02/2009 1 Brighton Ukulele Sundays – Songbook Faith by George Michael Well I guess it would be (C) nice, if I could touch your body I know not (F) everybody has got a body like (C) you.