Imaginationssighting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Era of Oil Well Drilling and Completions.Indd

Rod Pumping White Paper D352548X012 June 2020 New Era of Oil Well Drilling and Completions — Does It Require An Innovation In Rod Pumping? Abstract A new era of oil well drilling and completions is changing the face of rod pumping forever. Horizontal drilling with multistage hydraulic fracturing often results in very challenging production conditions. Pump placement below the kick-off (i.e., in non-vertical dogleg section), frequent gas slugs, large volumes of fl owback frac sand, signifi cant fl uctuations in fl uid fl ow rates, and steep decline curves are examples of the common challenges affecting the production of horizontal wells. Even the most sophisticated conventional pumpjack with an AC motor and variable frequency drive/variable speed drive (VFD/VSD) does not have the precise rod string control required to help mitigate and resolve many of these complex rod pumping issues that are frequently associated with horizontal multistage, hydraulically fractured wells. Linear pumping units, and more specifi cally linear hydraulic pumpjacks, have fundamental differences in geometry and control capabilities. Coupled with the fact that both natural gas and AC drive units support the same functionality, linear hydraulic pumpjacks provide the sophisticated rod string control required by today’s demanding wells. This paper will compare and contrast the different rod pumping methods and their abilities to address these production challenges. The paper will also discuss the additional benefi ts of combining the unique capabilities of a linear hydraulic pumpjack with sophisticated optimization control and remote access. The combination of these three key features provides an unprecedented solution that has the potential to become the next-generation rod pumping technology for cost effectively producing today’s challenging wells. -

The Great Shale Shut-In Is Underway, but Questions Linger on Long-Term Impact

Exclusive The great shale shut-in is underway, but questions linger on long-term impact Allison Good, Bill Holland, Corey Paul, Mark Passwaters 2,177 words 8 June 2020 SNL Canada Energy Week PWCAN Issue: 110130 English Copyright © 2020 by S&P Global Market Intelligence, a division of S&P Global Inc. All rights reserved. A pumpjack near Oklahoma City on April 21. Thousands of oil wells are shut in across the most prolific shale basins in the U.S., an unprecedented situation caused by the coronavirus-fueled crash in oil prices and a massive supply glut.Source: AP Photo U.S. shale drillers needed to slash oil production fast and deep as the coronavirus pandemic vaporized demand, tanked prices and left the world awash in unwanted crude. Natural production declines from spending cuts and canceled drilling plans were not anticipated to be enough to avoid hitting the physical limits of oil storage capacity, a potential crisis that caused benchmark crude oil futures to plunge into negative territory in April. So oil and gas companies large and small ranked their assets, well by well, and chose which ones to keep pumping, which ones to throttle back and which ones to shut down, maybe for good. It was, for many, a brutal calculus that resulted in thousands of wells getting shuttered in the country's most prolific oil provinces, and it created a great experiment involving well operations and geology that those inside and outside the industry are watching closely. "We just tromped on the brake pedal with both feet and slowed down production dramatically, such that it looks like we are going to get through" veteran Midland-based oilman Kyle McGraw said in an interview. -

Technical Report

TECHNICAL REPORT April 22, 2018 Alberta Upstream Oil & Gas Methane 2019 Emissions Inventory and Methodology Prepared For: Alberta Energy Regulator Suite 1000, 250 – 5th Street SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 0R4 Prepared by: Clearstone Engineering Ltd. 700, 900-6th Avenue S.W. Calgary, AB, T2P 3K2 Contact: Yori Jamin, M.Sc., P.Eng. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.clearstone.ca DISCLAIMER While reasonable effort has been made to ensure the accuracy, reliability and completeness of the information presented herein, this report is made available without any representation as to its use in any particular situation and on the strict understanding that each reader accepts full liability for the application of its contents, regardless of any fault or negligence of Clearstone Engineering Ltd. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents a detailed inventory of 2018 methane emissions from the upstream oil and natural gas (UOG) sector in Alberta, and delineates the boundaries, methodologies and data sources used. The type and quality of emissions, activity and infrastructure data available for use in this emissions inventory has improved and enables a progressively more refined assessment compared to previous inventories for the UOG sector (ECCC, 2014). The updated inventory is intended for use by the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) and its evaluation of methane emissions from the UOG sector. As such, inventory refinements and boundaries considered in this report focus on subsectors and activities contributing the most to UOG methane emissions. This effort may also inform Canada’s National Inventory Report submission to the UNFCCC Secretariat. Moreover, software tools developed by this project may be leveraged to establish a methane baseline (for 2012 and/or 2014 inventory years) and demonstrate achievement of provincially and federally stated methane reduction targets. -

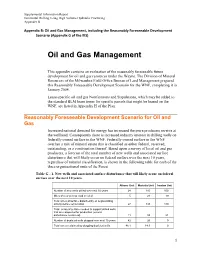

Oil and Gas Management, Including the Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario (Appendix G of the EIS)

Supplemental Information Report Horizontal Drilling Using High Volume Hydraulic Fracturing Appendix B Appendix B: Oil and Gas Management, including the Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario (Appendix G of the EIS) Oil and Gas Management This appendix contains an evaluation of the reasonably foreseeable future development for oil and gas resources under the Wayne. The Division of Mineral Resources of the Milwaukee Field Office Bureau of Land Management prepared this Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario for the WNF, completing it in January 2004. Lease-specific oil and gas Notifications and Stipulations, which may be added to the standard BLM lease terms for specific parcels that might be leased on the WNF, are listed in Appendix H of the Plan. Reasonably Foreseeable Development Scenario for Oil and Gas Increased national demand for energy has increased the price producers receive at the wellhead. Consequently there is increased industry interest in drilling wells on federally owned surface in the WNF. Federally owned surface in the WNF overlies a mix of mineral estate that is classified as either federal, reserved, outstanding, or a combination thereof. Based upon a survey of local oil and gas producers, a forecast of the total number of new wells and associated surface disturbance that will likely occur on federal surface over the next 10 years, regardless of mineral classification, is shown in the following table for each of the three organizational units of the Forest Table G - 1. New wells and associated surface disturbance -

Approaches for Integrating Renewable Energy Technologies in Oil and Gas Operations

Approaches for Integrating Renewable Energy Technologies in Oil and Gas Operations Sean Ericson, Jill Engel-Cox, and Doug Arent The Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis is operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Colorado School of Mines, the Colorado State University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Stanford University. Technical Report NREL/TP-6A50-72842 January 2019 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Approaches for Integrating Renewable Energy Technologies in Oil and Gas Operations Sean Ericson, Jill Engel-Cox, and Doug Arent The Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis is operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Colorado School of Mines, the Colorado State University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Stanford University. JISEA® and all JISEA-based marks are trademarks or registered trademarks of the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. The Joint Institute for Technical Report Strategic Energy Analysis NREL/TP-6A50-72842 15013 Denver West Parkway January 2019 Golden, CO 80401 303-275-3000 • www.jisea.org Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This work was authored in part by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. -

Signature Redacted Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Signature Redacted May 7, 2018 Certified by Choon S

A Novel Framework for Acoustic Diagnostic of Artificial Lift System for Oil-Production by Sebastien Karim Mannai S.M., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA (2014) S.M., Ecole Centrale Paris, France (2013) S.M., Universit6 de Paris-Saclay, France (2013) Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2018. All rights reserved. Au thr Signature redacted Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Signature redacted May 7, 2018 Certified by Choon S. Tan Senior Research Engineer, MIT Signature redacted Thesis Supervisor Certified by.. Tianxiang Su Researchngineer, Schlumberger Doll Research Center Committee Member Certified by.. Signaure edaced Alexander H. Slocum Professor of Mechanical Engineering, MIT Committee Member Certified by..Signature redacted Manuel Martinez Sanchez Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Engineering , MIT Committee Member Accepted by .... Signature redacted MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Hamsa Balakrishnan Associate Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics JUN 28 2018 Chair, Graduate Program Committee LIBRARIES ARCHIVES A Novel Framework for Acoustic Diagnostic of Artificial Lift System for Oil-Production by Sebastien Karim Mannai Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 7, 2018, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Oil extraction on many reservoirs requires the use of rod pump systems to pump the fluid to the surface. A longstanding challenging issue in the operation of rod- pump system is the ability to determine the downhole pump conditions based on the knowledge of a finite set of measurables at the top. -

How Texas Law Promoted Shale Play Development

How Texas Law Promoted Shale Play Development By Bill Kroger, Jason Newman, Ben Sweet, and Justin Lipe In 2015, Baker Botts celebrated its 175th anniversary. The firm’s energy practices date back to Spindletop (1901). More than one hundred years later, Texas remains a leading producer of oil and gas in the United States, and Baker Botts represents many of the energy companies that have revolutionized the industry with horizontal drilling in the Texas shale plays. In this article, four Baker Botts attorneys summarize developments in Texas law that have caused Texas to be a leader in oil and gas production. he production of oil and gas from shale plays in the past ten years, much of it in TTexas, has transformed the economies of the world. Hydrocarbons produced from the Eagle Ford and Barnett shale plays, as well as the Permian Basin and other places in Texas, have made the United States more energy independent, disrupted OPEC cartel economics, and strained oil-dependent economies from Argentina to Russia. As the supply of shale oil and gas has risen, energy prices have collapsed worldwide, lowering the cost of production for goods across the United States, reducing transportation costs for millions of Americans, and making U.S. manufacturing more competitive. Some observers argue that these transformations, while undeniably economically advantageous, have curtailed the development of renewable energy resources and contributed further to global environmental change. Texas ingenuity and technology drove the developments that led to the recovery of hydrocarbons from shale and other tight rock plays. Technical difficulties of producing hydrocarbons from shales, which have low permeabilities and vary in brittleness, had to be overcome.1 Important new technologies, such as horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and 3-D seismic imaging, allowed for this type of development. -

Spill Prevention, Control & Countermeasure (SPCC) Plan

3203 SE Woodstock Blvd, Portland, Oregon 97202 Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure Plan (SPCC) Document Prepared in 2004 by: Reed College Environmental Health and Safety Office Kathleen Fisher, EHS Director Phone: 503-777-7788 Fax: 503-777-7274 Email: [email protected] Document Amended in 2009, 2010, 2014, 2016, 2017, 2019 by: EHS Departmental Associates Original Plan Certification by: William E. Lawson, P.E. Environmental Engineer Portland General Electric Co. Phone: 503-464-8030 Fax: 503-464-7503 Original Implementation Date of Plan: November 2, 2004. This plan is fully implemented under Reed College management approval and direction. Reed College management personnel must review and evaluate this plan at least once every five years or whenever there is a change in design, operation, or maintenance that could significantly affect the plan. After this review and evaluation, school personnel must amend the SPCC Plan within six months of the review. Current copies of the Plan are readily available at the Community Safety Office, the Environmental Health and Safety Office, and the Facilities Services Office. [40 CFR Parts 112.3 & 112.5] SPCC_2016_7.docx Reed College Emergency Telephone Numbers [40 CFR Parts 112.7(a)(3)(vi)] Reed Community Safety Emergency 503-788-6666, ext. 6666 Fire/Police 911 NRC Environmental 1-800-337-7455 (Clean-up Contractors) Or 503-283-1150 Chemtrec (Specialty Spill Responders) 1-800-424-9200 Poison Control 1-800-222-1222 Safety & Supply Co. 503-283-9500 (Supplies and Equipment) National Response Center 1-800-424-8802 -

Characterization of Oil and Gas Production Equipment and Develop a Methodology to Estimate Statewide Emissions

ERG No. 0227.03.026 TCEQ Contract No. 582-7-84003 Work Order No. 582-7-84003-FY10-26 Characterization of Oil and Gas Production Equipment and Develop a Methodology to Estimate Statewide Emissions FINAL REPORT TCEQ Contract No. 582-7-84003 Work Order No. 582-7-84003-FY10-26 Prepared by: Mike Pring, Daryl Hudson, Jason Renzaglia, Brandon Smith, and Stephen Treimel Eastern Research Group, Inc. 1600 Perimeter Park Drive Morrisville, NC 27560 Prepared for: Martha Maldonado Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Air Quality Division November 24, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 AVAILABLE EMISSIONS ESTIMATION METHODOLOGY REVIEW................. 2-1 3.0 IDENTIFICATION OF OIL AND GAS OWNERS/OPERATORS AND SURVEY DEVELOPMENT................................................................................................................... 3-1 4.0 EMISSIONS CALCULATION METHODOLOGY.................................................... 4-1 4.1 Compressor Engines ........................................................................................ 4-1 4.2 Artificial Lift (Pumpjack) Engines ................................................................. 4-15 4.3 Dehydrators ................................................................................................... 4-20 4.3.1 Dehydrator -

Hydrocarbons: a Fossil but Not (Yet) Extinct Image Courtesy of the Shell Library

sis_12_RZ:Layout 1 31.07.2009 12:31 Uhr Seite 62 Hydrocarbons: a fossil but not (yet) extinct Image courtesy of the Shell Library Continuing our energy series, Menno van Dijk introduces us to the past, present and future of hydrocarbons – still the most common of all fuels. hile researchers today are isms. They all extracted the energy for Wworking on the development their organic molecules either directly of clean, renewable fuels, our society or indirectly from sunlight. is still almost entirely dependent on fossil fuels. How are they formed, Storage in reservoirs how much is there of them, and how Since then, the continents have long will they last? drifted apart, with some landmasses Hundreds of millions of years ago, disappearing into the depths and oth- the world was a wilderness, but not ers being heaved up. Wind, ice and void. A diversity of animals and rain caused erosion on land, which plants populated the landmass. The created great masses of sediment, seas bubbled with life and, like today, especially in river estuaries. Some the largest part of the biomass con- sediments were porous (such as sand sisted of microscopically small organ- or the skeletons of calcareous ani- mals), others impermeable (such as ly of carbon (C) and hydrogen (H), clay). Organic material was buried, they are collectively called ‘hydrocar- too, and the vertical movements of bons’. This fluid, mostly together with landmasses could take it several kilo- water that was also trapped, worked metres below the ground. There, it its way up through porous rock until was warmed up by heat from the it was – in some cases – stopped by interior of Earth. -

APPENDIX D Emergency Planning and Response General Project Contacts GENERAL PROJECT CONTACTS

APPENDIX D Emergency Planning and Response General Project Contacts GENERAL PROJECT CONTACTS National Grid Toll-Free Telephone Number for construction-related complaints or concerns: (800) 356-0050 National Grid Project Management Contact Tom Brim, Project Manager 300 Erie Boulevard West Syracuse, NY 13202 315-428-5012 Email: [email protected] National Grid Construction Management Contact Pete Doster 300 Erie Boulevard West Syracuse, NY 13202 315-428-5103 Email: [email protected] NYS Department of Public Service General Complaint Contact Three Empire State Plaza Albany, NY 12223 800-342-3377 (8:30 am – 4:00 pm) DPS Environmental Compliance Section James Austin, Deputy Director Three Empire State Plaza Albany, NY 12223 518-4025786 Richard Powell Three Empire State Plaza Albany, NY 12223 518-486-2885 Honorable Kathleen H. Burgess Secretary of State of New York Public Service Commission Three Empire State Plaza 20th Floor Albany, NY 12223 518-474-6530 Environmental Monitor (To be confirmed prior to construction) Table D-1 List of Residences Within 100 Feet Table D-1 Five Mile Road Station Project List of Residences Within 100 Feet Residence Tax Parcel Property Owner Name Owner Mailing Address Within 100 Number Address Feet 4 Rowland Avenue, 67.003-1-5 Cooper Hill Road Eric D. Farr No Cheektowaga, NY 14225 4650 Five Mile Raymond & 4650 Five Mile Road, 76.001-2-2.3 No Road Nancy Survil Allegany, NY 14706 4557 Five Mile Kent & Barbara 4557 Five Mile Road, 76.001-1-6.1 Yes Road Cobado Allegany, NY 14706 4544 Five Mile -

Artificial Lift Technology Meets Increasing Challenges Of

DRILLING & COMPLETIONS PHOTO: PUMPWELL SOLUTIONS PUMPWELL PHOTO: DRILLING & COMPLETIONS pump off many wells that other artifi cial lift ARTIFICIAL LIFT TECHNOLOGY methods cannot. “Th e older styles of jet pump were typ- ically set up so all wellbore liquids and gas MEETS INCREASING CHALLENGES came through the jet pump. While jet pumps are an excellent multi-phase pump, Source Rock is well aware that as you approach OF UNCONVENTIONAL WELLS pumped-off conditions, the volumetric ex- pansion of a gas phase will require more and more jet pump horsepower. By Carter Haydu “By installing concentric-tubing jet- pump completions, gas is produced up the he shadoof was once the pinnacle of ever before that the operator know when casing annulus, and the jet pump horse- artifi cial lift technology, moving water problems occur in the well and then make power is focused on lifting the wellbore Tfrom its shallow reservoir to another the necessary corrections. “When you have liquids and solids. Th ere is no sense in using nearby locale with relative ease on the part precise rod-string control, it is amazing the the jet pump to pump gas because the gas of its ancient Egyptian operator. things you can do. You can perform subtle, will fl ow to surface on its own.” Flash forward a few thousand years and small manipulations to the speeds and ac- For Nav Dhunay, president and chief ex- contemporary successor lift technologies celerations of how you actuate this pump ecutive offi cer at PumpWELL Solutions, the in the North American oil and gas sector and actually resolve issues.” latest innovations in the artifi cial lift space are basically performing the same task as SilverJack is Zedi’s hydraulic rod-pumping have little to do with the actual, physical their BCE counterparts (moving valuable solution.