The Role of Skill Versus Luck in Poker: Evidence from the World Series of Poker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How We Learned to Cheat in Online Poker: a Study in Software Security

How we Learned to Cheat in Online Poker: A Study in Software Security Brad Arkin, Frank Hill, Scott Marks, Matt Schmid, Thomas John Walls, and Gary McGraw Reliable Software Technologies Software Security Group Poker is card game that many people around the world enjoy. Poker is played at kitchen tables, in casinos and cardrooms, and, recently, on the Web. A few of us here at Reliable Software Technologies (http://www.rstcorp.com) play poker. Since many of us spend a good amount of time on-line, it was only a matter of time before some of us put the two interests together. This is the story of how our interests in online poker and software security mixed to create a spectacular security exploit. The PlanetPoker Internet cardroom (http://www.planetpoker.com) offers real-time Texas Hold'em games against other people on the Web for real money. Being software professionals who help companies deliver secure, reliable, and robust software, we were curious about the software behind the online game. How did it work? Was it fair? An examination of the FAQs at PlanetPoker, including the shuffling algorithm (which was ironically published to help demonstrate the game's integrity), was enough to start our analysis wheels rolling. As soon as we saw the shuffling algorithm, we began to suspect there might be a problem. A little investigation proved this intuition correct. The Game In Texas Hold'em, each player is dealt two cards (called the pocket cards). The initial deal is followed by a round of betting. After the first round of betting, all remaining cards are dealt face up and are shared by all players. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks Honoring the 2010 World

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks Honoring the 2010 World Series Champion San Francisco Giants July 25, 2011 The President. Well, hello, everybody. Have a seat, have a seat. This is a party. Welcome to the White House, and congratulations to the Giants on winning your first World Series title in 56 years. Give that a big round. I want to start by recognizing some very proud Giants fans in the house. We've got Mayor Ed Lee; Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom. We have quite a few Members of Congress—I am going to announce one; the Democratic Leader in the House, Nancy Pelosi is here. We've got Senator Dianne Feinstein who is here. And our newest Secretary of Defense and a big Giants fan, Leon Panetta is in the house. I also want to congratulate Bill Neukom and Larry Baer for building such an extraordinary franchise. I want to welcome obviously our very special guest, the "Say Hey Kid," Mr. Willie Mays is in the house. Now, 2 years ago, I invited Willie to ride with me on Air Force One on the way to the All-Star Game in St. Louis. It was an extraordinary trip. Very rarely when I'm on Air Force One am I the second most important guy on there. [Laughter] Everybody was just passing me by—"Can I get you something, Mr. Mays?" [Laughter] What's going on? Willie was also a 23-year-old outfielder the last time the Giants won the World Series, back when the team was in New York. -

Greetings! for the 13,000 Students in Our Programs Nationwide, the Start of Fall Is About More Than Going Back to School. for Ma

Greetings! For the 13,000 students in our programs nationwide, the start of fall is about more than going back to school. For many, it’s the opportunity to reconnect with our counselors and our safe rooms. From preparing for our Domestic Violence Awareness Month campaigns, to partnering with baseball teams (both minor AND major), to celebrating a big milestone, we have so much to share with you. Check out some highlights from Safe At Home! Sneak Peak: DV Awareness Month Planning Every October, Safe At Home commemorates Domestic Violence Awareness Month by holding school-wide awareness campaigns at all of our 15 locations. A group of students – known as peer leaders – will work with the therapist to spread the word throughout their school, using skills like leadership and advocacy that they’ll continue to build throughout the year. This year’s theme is all about those skills, and more. “Your words are your power. How will you use yours?” will encourage students to look to the strengths and power they already possess to be an ally and advocate. We look forward to sharing stories about their campaign activities soon, but in the meantime, check out this beautiful campaign poster made by Safe At Home’s alumni intern, Julissa. Did you know that a gift of just $250 can help us buy the supplies we need for an awareness campaign for one entire school? Visit joetorre.org/donate to make a gift of any size to support our awareness campaigns. Partnership with Minor League Baseball Raises $5000+ Safe At Home partnered with Minor League Baseball for our third annual Domestic Violence Awareness Night campaign this summer. -

Testimony Opposing House Bill 1389 Mark Jorritsma, Executive Director Family Policy Alliance of North Dakota March 15, 2021

Testimony Opposing House Bill 1389 Mark Jorritsma, Executive Director Family Policy Alliance of North Dakota March 15, 2021 Good morning Madam Chair Bell and honorable members of the Senate Finance and Taxation Committee. My name is Mark Jorritsma and I am the Executive Director of Family Policy Alliance of North Dakota. We respectfully request that you render a “DO NOT PASS” on House Bill 1389. Online poker is not gambling. This bill says so itself, and more importantly, in August of 2012, a federal judge in New York ruled in US v. Dicristina that internet poker was not gambling.1 So that is settled. But is it really? While online poker does not appear to meet the legal definition of gambling, consider these facts. • In the same ruling referenced above, Judge Weinstein acknowledged that state courts that have ruled on the issue are divided as to whether poker constitutes a game of skill, a game of chance, or a mixture of the two.2 • Online poker, which allows players to play multiple tables at once, resulting in almost constant action, is a fertile ground for developing addiction. Some sites allow a player to open as many as eight tables at a time, and the speed of play is three times as fast as live poker.3 • …online poker has a rather addictive nature that often affects younger generations. College age students are especially apt to developing online poker addictions.4 • Deposit options will vary depending on the state, but the most popular method is to play poker for money with credit card. -

History of Texas Holdem Poker

GAMBLING History of Texas Holdem Poker ever in the history of poker has it been as popular as nowadays. The most played poker game is definitely exasT Hold em. All Nover the world people are playing Texas Hold em games and there seems to be no end to the popularity of the game. Espe- cially playing Texas Hold em for free on the Internet has became extremely popular in the last years. Who actually invented this great poker game? This was a game, played in the 15th century, that was played with the card deck as we know it Where did it originally come from? And how today. It was a card game that included bluffing and betting. did free Texas Hold em games end up on the internet? To answer these questions it is The French colonials brought this game to Canada and then to the United States in the early important to trace back the history of poker, to 17th century, but the game didn’t became a hit until the beginning of the 18th century in New find out where it all began. Orleans. HISTORY OF POKER THEORIES During the American Civil War, soldiers played the game Pogue often to pass the time, all over the country. Different versions evolved from this firstPogue game and they were called ‘‘Stud’’ There are many different theories about how and ‘‘Draw’’. The official name for the game turned into ‘‘Poker’’ in 1834 by a gambler named poker came into this world and there seems to Jonathan H. Green. be no real proof of a forerunner of the game. -

Remarks Honoring the 2009 World Series Champion New York Yankees April 26, 2010

Apr. 25 / Administration of Barack Obama, 2010 a stable and prosperous world. We are con- and effectively deal with the challenges of the vinced that, acting in the “spirit of the Elbe” new millennium. on an equitable and constructive basis, we can successfully tackle any tasks facing our nations NOTE: An original was not available for verifi- cation of the content of this joint statement. Remarks Honoring the 2009 World Series Champion New York Yankees April 26, 2010 Hello, everybody. Everybody have a seat, Sox fan like me, it’s painful to watch Mariano’s please. cutter when it’s against my team or to see the Yankees wrap up the pennant while the Sox [At this point, the President exchanged greet- are struggling on the South Side. Although, I ings with Yankees manager Joseph E. Girardi. do remember 2005, people, so—[laugh- He then continued his remarks as follows.] ter]—don’t get too comfortable. [Laughter] But for the millions of Yankees fans in New Hello, everybody, and welcome to the York and around the world who bleed blue, White House. And congratulations on being nothing beats that Yankee tradition: 27 World World Series champions. Series titles; 48 Hall of Famers—a couple, I As you can see, we’ve got a few Yankees expect, standing behind me right now. From fans here in the White House—[laugh- Ruth to Gehrig, Mantle to DiMaggio, it’s hard ter]—who are pretty excited about your visit. I to imagine baseball without the long line of want to actually start by recognizing Secretary legends who’ve worn the pinstripes. -

Bwin.Party Digital Entertainment Annual Report & Accounts 2012

Annual report &accounts 2012 focused innovation Contents 02 Overview 68 Governance 02 Chairman’s statement 72 Audit Committee report 04 A year in transition 74 Ethics Committee report 05 Our business verticals 74 Integration Committee report 06 Investment case 75 Nominations Committee report 10 Our business model 76 Directors’ Remuneration report 12 CEO’s review 90 Other governance and statutory disclosures 20 Strategy 92 2013 Annual General Meeting 28 Focus on our technology 94 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 30 Focus on social gaming 32 Focus on PartyPoker 95 Financial statements 95 Independent Auditors’ report 34 Review of 2012 96 Consolidated statement of 44 Markets and risks comprehensive income 97 Consolidated statement 46 Sports betting of fi nancial position 48 Casino & games 98 Consolidated statement of changes 50 Poker in equity 52 Bingo 99 Consolidated statement of cashfl ows 54 Social gaming 100 Notes to the consolidated 56 Key risks fi nancial statements 58 Responsibility & relationships 139 Company statement of fi nancial position 58 Focus on responsibility 140 Company statement of changes in equity 60 Customers and responsible gaming 141 Company statement of cashfl ows 62 Environment and community 142 Share information 63 Employees, suppliers and shareholders 146 Notice of 2013 Annual General Meeting 66 Board of Directors 150 Glossary Sahin Gorur Bingo Community Relations See our online report at www.bwinparty.com Overview Strategy Review Markets Responsibility & Board of Governance Financial Share Notice of Annual Glossary 01 of 2012 and risks relationships Directors statements information General Meeting Introduction 02 Chairman’s statement real progress We made signifi cant progress in 2012 and remain Our attentions are now turning to the on course to deliver all of the Merger synergies as next step in our evolution, one centred on innovation that will be triggered by Annual report & accounts 2012 originally planned. -

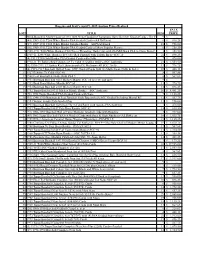

03/26/04 Chip / Token Tracking Time: 04:45 PM Sorted by City - Approved Chips

Date: 03/26/04 Chip / Token Tracking Time: 04:45 PM Sorted by City - Approved Chips Licensee ----- Sample ----- Chip/ City Approved Disapv'd Token Denom. Description LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 OLD MAN WITH HAT AND CANE. AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 25.00 AMARGOSA OPERA HOUSE AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 09/21/95 00/00/00 CHIP 100.00 TONOPAM AND TIDEWATER CO. AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 01/12/96 00/00/00 TOKEN 1.00 JACK LONGSTREET AMARGOSA LONGSTREET INN & CASINO 06/19/97 00/00/00 CHIP NCV, HOT STAMP, 3 COLORS AMARGOSA AMARGOSA VALLEY BAR 11/22/95 00/00/00 TOKEN 1.00 GATEWAY TO DEATH VALLEY AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 JULY 4, 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HALLOWEEN 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 THANKSGIVING 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 MERRY CHRISTMAS 1996! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HAPPY NEW YEARS 1997! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/18/96 00/00/00 CHIP 5.00 HAPPY EASTER 1997! AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 0.25 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 0.50 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 1.00 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON 06/21/96 00/00/00 CHIP 2.50 DORIS JACKSON, FIRST WOMAN OF GAMING AMARGOSA VALLEY STATELINE SALOON -

Facebook's New Home from the Inside

Business 2 SECTION August 3, 2011 ■ A LSO INSIDE C ALENDAR 24 |REAL ESTATE 25 |CLASSIFIEDS 29 irst look facebook’s new home from the inside out by sandy brundage | almanac staff writer f any office building has that coveted garage door on to a central courtyard. “new car” smell, it’s Facebook’s reno- Employees didn’t waste time before vated Menlo Park headquarters. leaving their mark on the building: An Earlier this year the social network- exquisitely sketched pink elephant trum- ing giant signed a 15-year leaseback peted from one blackboard wall; one iagreement for a 1-million-square-foot, worker found the perfect spot to display 11-building campus that used to house a short brown wig; a flower chalked in Sun and Oracle employees. It also bought pastels climbed another blackboard. two nearby lots on Constitution Drive, Plywood partitions screened some areas Photos courtesy of Facebook linked to the 57-acre Sun campus by a while climbing ropes fenced off others, the Above left: A meeting space at Facebook’s new home. Near the orange chair, climbing pedestrian tunnel under the Bayfront contribution of a contractor who climbs in ropes provide a partition that can double as a message board. At right: A phone booth Expressway. That gives Facebook the his spare time. Adding clothespins to hold stands ready for a private call — or Superman — at Facebook’s new headquarters. growing room to triple the number of notes will let the ropes double as a mes- employees to 6,100. sageboard. Overhead, ceiling ductwork The Almanac was the first newspaper looked stark, matching the undisguised the scarlet paint of the room’s door, John One favorite spot of lead designer to tour the renovated campus, on July 27, industrial feel of the office space. -

Phillies Sparkplug Shane Victorino Has Plenty of Reasons to Love His

® www.LittleLeague.org 2011 presented by all smiles Phillies sparkplug shane Victorino has plenty of reasons to love his job Plus: ® LeAdoff cLeAt Big league managers fondly recall their little league days softball legend sue enquist has some advice for little leaguers IntroducIng the under Armour ® 2011 Major League BaseBaLL executive Vice President, Business Timothy J. Brosnan 6 Around the Horn Page 10 Major League BaseBaLL ProPerties News from Little League to the senior Vice President, Consumer Products Howard Smith Major Leagues. Vice President, Publishing Donald S. Hintze editorial Director Mike McCormick 10 Flyin’ High Publications art Director Faith M. Rittenberg Phillies center fielder Shane senior Production Manager Claire Walsh Victorino has no trouble keeping associate editor Jon Schwartz a smile on his face because he’s account executive, Publishing Chris Rodday doing what he loves best. associate art Director Melanie Finnern senior Publishing Coordinator Anamika Panchoo 16 Playing the Game: Project assistant editors Allison Duffy, Chris Greenberg, Jake Schwartzstein Albert Pujols editorial interns Nicholas Carroll, Bill San Antonio Tips on hitting. Major League BaseBaLL Photos 18 The World’s Stage Director Rich Pilling Kids of all ages and from all Photo editor Jessica Foster walks of life competed in front 36 Playing the Game: Photos assistant Kasey Ciborowski of a global audience during the Jason Bay 2010 Little League Baseball and Tips on defense in the outfield. A special thank you to Major League Baseball Corporate Softball World Series. Sales and Marketing and Major League Baseball 38 Combination Coaching Licensing for advertising sales support. 26 ARMageddon Little League Baseball Camp and The Giants’ pitching staff the Baseball Factory team up to For Major League Baseball info, visit: MLB.com annihilated the opposition to win expand education and training the world title in 2010. -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr. -

Steve Brecher Wins $1,025,500 Poker Palooza

FAIRWAY JAY’S MASTERS PREVIEW ROUNDERLIFE.com KEN DAVITIAN BORAT’S CHUM EXUDES CHARISMA AND CLASS ROY JONES JR Y’ALL MUST HAVE FORGOT STEVE BRECHER WINS $1,025,500 NICK BINGER SURVIVING LONGEST FINAL FROM $50 TABLE IN WPT HISTORY TO $1,000,000 ALL CANADIAN FINAL WSOP CIRCUIT EVENT FEATURED MONTREAL’S SAMUEL CHARTIER VS POKER TORONTO’S JOHN NIXON PALOOZA APRIL 2009 $4.95US DREAM A LITTLE DREAM INSIDE: POKER + ENTERTAINMENT + FOOD + MUSIC + SPOR T S + G I R L S Live the EXCLUSIVE WEB VIDEO AT ROUNDERLIFE.COM ROUNDER GIRLS AFTER DARK • PLAYER INTERVIEWS HOT NEWS AND EVENTS CASINO AND RESTAURANT REVIEWS BEHIND THE SCENE FOOTAGE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Before you can be a legend, PUBLISHER You gotta get in the game. he World Series of Poker Circuit Event, recently held at Caesars Atlantic Greg McDonald - [email protected] City, has consistently become one of the most well attended events on the circuit schedule. e eleven tournaments that took place from Mach 4th - 14th attracted EDITOR-IN-CHIEF T Evert Caldwell - [email protected] over 5000 players and generated more than $3 million dollars in prize money. is years champion was 23 year old Montreal, Quebec native, Samuel Chartier. e young pro MANAGING EDITOR took home $322,944, and the Circuit Champion’s gold ring for his eff ort. Second place Johnny Kampis fi nisher John Nixon from Toronto, Ontario, made it an All Canadian fi nal. e full time student took home $177,619. Could this be the year a Canadian wins the WSOP Main CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Event ? Canadians were well represented at last years Main Event, making up the highest Dave Lukow percentage of players from a country outside of the US.