AN INTERVIEW with TISSA KARIYAWASAM on ASPECTS of Title CULTURE in SRI LANKA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the PDF File

THORATHURUby Sri Lanka Association of NSW Inc OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER FIRST EDITION 2020 IMPACT OF COVID 19 PANDEMIC ON HUMAN BEHAVIOUR ALBERT EINSTEIN’S OBSCURE VISIT TO SRI LANKA IN 1922 WHY DO JAFFNA PEOPLE SHAKE THEIR LEGS IN SITTING POSITION? THE HISTORY & SIGNIFICANCE OF POSON POYA Sri Lankan pole fishermen in Midigama Credit: @woolgarz Let us acknowledge the traditional owners of this land where we are across NSW and pay our respect to elders past and present. The land and their culture have over 65 thousand years’ history and today with more than 270 multicultural nations enriching this land. PAGE 1 EDITOR'S MESSAGE 1 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE 2 EDITOR'S MESSAGE DINESH RANASINGHE COMMITTEE 2020 4 [email protected] HIGHLIGHTS OF FIRST HALF “Life imposes things on you that you can’t control, OF YEAR ACTIVITIES 5 but you still have the choice of how you’re going to EVENTS live through this." Sri Lankan Flag Raising Ceremony 7 - Celine Dion Young Achiever 9 Senior Luncheon 15 It is indeed a great honour to A huge thank you to all the be the Editor for Thorathuru people who contributed ARTICLES and it is an immense writing the wonderful and pleasure to launch this first inspiring articles, without Impact of Covid 19 Pandemic edition for 2020. which there wouldn’t have on Human Behaviour 16 been this newsletter issue. In this issue, we will recount Cow’s MILK Considered a the various projects and Last but not least, I would like Holy Drink 23 activities in which SLANSW to thank SLANSW President, members were actively Nalika Padmasena, and The History and Significance of involved. -

The Fukuoka City Public Library Movie Hall Ciné-Là Film Program Schedule December 2015

THE FUKUOKA CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY MOVIE HALL CINÉ-LÀ FILM PROGRAM SCHEDULE DECEMBER 2015 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARCHIVE COLLECTION VOL.9 ACTION FILM ADVENTURE WITH YASUAKI KURATA December 2-6 No English subtitles ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SRI LANKA FILMS CENTERED ON LESTER JAMES AND SUMITRA PERIES December 9-26 English subtitles ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Our library and theater will be closed for the New Year Holidays from December 28-January 4 ENGLISH HOME PAGE INFORMATION THE FUKUOKA CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY http://www.cinela.com/english/ This schedule can be downloaded from: http://www.cinela.com/english/newsandevents.htm http://www.cinela.com/english/filmarc.htm ARCHIVE COLLECTION VOL.9 Action Film Adventure with Yasuaki Kurata A collection of films starring action film star Yasuaki Kurata. December 2-6 No English subtitles TATAKAE! DRAGON VOL.1 Director: Toru Toyama, Shozo Tamura Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Bruce Liang, Makoto Akatsuka 1974 / Digital / Color / 80 min./ No English subtitles STORY: 4 episodes from the 1974 TV series pitting a karate expert as the protagonist who goes against an underworld syndicate. (Episodes 1-4) TATAKAE! DRAGON VOL.2 Director: Toru Toyama Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Fusayo Fukawa, Noboru Mitani / Digital / Color / 80 min./ No English subtitles STORY: 4 episodes from the 1974 TV series pitting a karate expert as the protagonist who goes against an underworld syndicate. (Episodes 14, 15, 25, 26) FINAL FIGHT SAIGO NO ICHIGEKI Director: Shuji Goto Cast: Yasuaki Kurata, Yang Si, Simon Yam 1989 / 35mm/ Color / 96min./ No English subtitles STORY: A former Asian karate champion struggles as he makes a comeback. A big hit that was shown in 33 countries. -

'Deyyo Sakki' to Be Staged 'Gee Ranga Siri' at Lionel Wendt

‘Deyyo Sakki’ to be staged The play ‘Deyyo January Sakki’ is a satirical 22 comedy, a pun on our so called commercial society. We all start our day with rituals and prayers, pleading to SARASHI SAMARASINGHE God to fulfill our dreams, desires and aspirations. This week’s `Cultural Diary’ brings you details about several other What would happen if fascinating events happening in the city. Take your pick of stage God (Sakkra) himself plays, exhibitions or dance performance and add colour to your appears in our presence? routine life. You can make merry and enjoy the adventures or sit The reaction and the inter- January 22. The cast and Sanath Sri Malsara. back, relax and enjoy a movie of your choice. Make a little space action of the mercenaries includes Bandula Wijew- Music will be by Bandula to kick into high gear amid the busy work schedules to enjoy the with the almighty is the eera, Gunadasa Madurasin- Wijeweera, lyrics and cos- exciting events happening at venues around the city. If there is an subject of this humorous ghe, Anoma Kumudini, tumes by Chinthani Hindu- play. Venuri Wijeweera, Chamin- rangala, make up by Jayan- event you would like others to know, drop an email to eventcalen- ‘Deyyo Sakki’ will be da Prasad, Menike Attanay- tha Kapuge while script [email protected] (Please be mindful to send only the essential staged at the Samudra ake, Chinthani Hindu- and direction by Dr.Anura details). Have a pleasant week. Devi Balika, Nugegoda on rangala, Nirmani Perera Chandrasiri. ‘Architect 2013’ at BMICH February ‘Architect 2013,’Members’ Work & Trade Exhibition will be held at the BMICH from 20 February 20 to 24. -

Sri Lanka Et Maldives Symboles

Jacques Soulié ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Sri Lanka et Maldives Symboles Distance entre l’aéroport et le centre-ville Prix du trajet en train Temps de trajet Prix du trajet en bus Prix de la course en taxi Prix du trajet en bateau Hôtels oo Simple et confortable ooo Bon confort oooo Grand luxe, ooooo Très grand luxe très confortable Restaurants Très bonne table. Prix élevés Bonne table. Prix abordables Table simple. Bon marché © Les Guides Mondéos Titres de la collection : Afrique du Sud, Algérie, Allemagne, Alsace, Amsterdam, Andalousie, Angleterre et pays de Galles, Antilles françaises, Argentine, Arménie, Asie centrale, Australie, Autriche, Azerbaïdjan, Baléares, Bali/Lombok/Java- Est/Sulawesi, Barcelone, Belgique, Berlin, Birmanie (Myanmar), Brésil, Budapest, Bulgarie, Cambodge/Laos, Canada, Canaries, Cap-Vert, Caraïbes, Chili, Chine, Chypre, Corse, Costa Rica/Panamá, Crète, Croatie, Cuba, Danemark/Copenhague, Dubaï/Oman, Ecosse, Egypte, Equateur et les Îles Galápagos, Espagne, Etats-Unis Est, Etats-Unis Ouest, Finlande/Laponie, Florence et Toscane, Floride/Louisiane/Texas et Bahamas, Guatemala, Grèce et les îles, Hongrie, Iles Anglo-Normandes, Ile Maurice, Inde du Nord/Népal, Inde du Sud, Irlande, Islande, Israël, Istanbul, Italie du Nord, Italie du Sud, Japon, Jordanie/Syrie/Liban, Kenya/Tanzanie/Zanzibar, La Réunion, Libye, Lisbonne, Londres, Madagascar, Madère et les Açores, Madrid, Malaisie et Singapour, Maldives (atolls/plongées/ spa), Malte, Maroc, Marrakech, Mauritanie, Mexique et Guatemala, Monténégro, Moscou et Saint-Pétersbourg, New York, Nicaragua, Norvège, Océan Indien, Paris, Pays baltes, Pays-Bas, Pérou/Bolivie, Plongée en mer Rouge, Pologne, Portugal, Prague, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, Québec et Ontario, République dominicaine, République tchèque, Rome, Roumanie, Sardaigne, Sénégal, Seychelles, Sicile, Sri Lanka/Maldives, Suède, Tahiti et Polynésie française, Tanzanie/Zanzibar, Thaïlande, Tunisie, Turquie, Venise, Vienne, Vietnam… Crédit photos : Patrick de Panthou, P. -

SAARC Film Festival 2017 (PDF)

Organised by SAARC Cultural Centre. Sri Lanka 1 Index of Films THE BIRD WAS NOT A BIRD (AFGHANISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Ahmad Zia Arash THE WATER (AFGHANISTAN/ SHORT) Directed by Sayed Jalal Rohani ANIL BAGCHIR EKDIN (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Morshedul Islam OGGATONAMA (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Tauquir Ahmed PREMI O PREMI (BANGLADESH/ FEATURE) Directed by Jakir Hossain Raju HUM CHEWAI ZAMLING (BHUTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Wangchuk Talop SERGA MATHANG (BHUTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Kesang P. Jigme ONAATAH (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Pradip Kurbah PINKY BEAUTY PARLOUR (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Akshay Singh VEERAM MACBETH (INDIA/ FEATURE) Directed by Jayaraj ORMAYUDE AtHIRVARAMBUKAL (INDIA/ SHORT) Directed by Sudesh Balan TAANDAV (INDIA/ SHORT) Directed by Devashish Makhija VISHKA (MALDIVES/ FEATURE) Directed by Ravee Farooq DYING CANDLE (NEPAL/ FEATURE) Directed by Naresh Kumar KC THE BLACK HEN (NEPAL/ FEATURE) Directed by Min Bahadur Bham OH MY MAN! (NEPAL/ SHORT) Directed by Gopal Chandra Lamichhane THE YEAR OF THE BIRD (NEPAL/ SHORT) Directed by Shenang Gyamjo Tamang BIN ROYE (PAKISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Momina Duraid and Shahzad Kashmiri MAH-E-MIR (PAKISTAN/ FEATURE) Directed by Anjum Shahzad FRANGIPANI (SRI LANKA/ FEATURE) Directed by Visakesa Chandrasekaram LET HER CRY (SRI LANKA/ FEATURE) Directed by Asoka Handagama NAKED AMONG PUBLIC (SRI LANKA/ SHORT) Directed by Nimna Dewapura SONG OF THE INNOCENT (SRI LANKA/ SHORT) Directed by Dananjaya Bandara 2 SAARC CULTURAL CENTRE SAARC Cultural Centre is the multifaceted realm of to foray into the realm of the SAARC Regional Centre the Arts. It aims to create an publications and research and for Culture and it is based in inspirational and conducive the Centre will endeavour to Sri Lanka. -

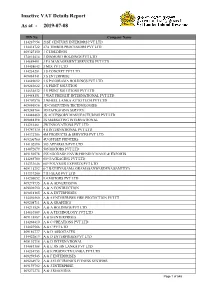

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

MIDWEEK P1 18-11.Qxd

Wednesday 18th November 2009 I next encountered Henry Janaki. However, it is not impossi- Jayasena in another film that I ble that something of Henry quite like — G. D. L. Perera’s Jayasena’s inspiration that lin- Dahasak Sithuvili. The image of gered in the class rooms of that Henry Jayasena in this film as a school may have rubbed off on the distraught and dejected lover young Manorathne years later! crumpling several old love letters Henry Jayasena left Dehipe and casting them to the waters Primary School a few months after flowing by remains in my mind’s joining it on getting through the eye despite the passage of years. General Clerical Service And, of course, there are his unfor- Examination to join the Public gettable roles as Piyal in Works Department (PWD) of Sri Gamperaliya and Azdak in Lanka. His longest stint in a regu- Hunuwataye Kathawa, his superb lar job was in this now defunct adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s The PWD. These were also years when Caucasian Chalk Circle.Thehe was at his creative best during hauntingly beautiful song from which he wrote, translated, adapt- Kuveni — Andakaren ed and directed his well known Duratheethe— which Henry plays Janelaya (1962), Thavath sions (pahan sangveda is another by Tissa Jayatilaka Henry Jayasena passed part we must. Thank you, Jayasena sings with that other fab- Udesenak (1964), Manaranjana example he cites in the book under away on the 11th of Henry, for the years of ulous star of the Sinhala stage and Wedawarjana (1965), Ahas Malilga comment) that do not translate November after a battle superb theatre and commit- screen Wijeratne Warakagoda, has (1966), Hunuwataye Kathawa adequately or properly into with cancer. -

1905-34 E.Pdf

II fldgi — YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2015'03'13 1A PART II — GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 13.03.2015 Name of Notary Judicial Main Office Date of Language Division Appointment Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 1905$34 - 2015 ud¾;= ui 13 jeks isl=rdod - 2015'03'13 No. 1905/34 - FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2015 (Published by Authority) PART II : List of Notaries The List of Notaries in Sri Lanka - 31st December, 2014 Land Registry : Colombo Name of Notary Judicial Main Office Date of Language Division Appointment Abayarathne K.S.R. Colombo No.83,Rosmid Place,Col. 07 2013.03.08 English Abayasundara Y.H. Colombo No.62/2,Sri Darmakeerthiyarama Mw.,Col.03 2012.04.18 Sinhala Abdeen A. Colombo 282/23, Dam Street, Colombo 12 Abdeen M.N.N. Colombo Level 14, BOC Merchent Tower, 28, St Michael’s Rd., Colombo 3. Abdul Carder M.K. Colombo Abdul Kalam M.M. Colombo Abeygunawardena S.D. Colombo 35D/4, Munamalgama, Waththala Rd, Polhena Abeygunawardena W.D. Colombo CL/1/10,Gunasinghepura,Colombo 12 1950.04.22 Sinhala/English Abeykoon A.M.C.W.P. Colombo 15,Salmal Uyana,Wanawasala,Kelaniya 2010.05.20 Sinhala Abeykoon B.M. Colombo No.123/5,Pannipitiya Road,Battaramulla 2005.10.07 Sinhala/English Abeykoon Y.T. Colombo BX5, Manning Town, Elvitigala Mw., Colombo 8 Abeynayake E.H. -

The Sinhala Theatre of the Eighties: a Forum for Creative Criticism*

THE SINHALA THEATRE OF THE EIGHTIES: A FORUM FOR CREATIVE CRITICISM* Ranjini Obeyesekere The past decade has been a time of political upheaval, of violence, terror, and repression. Such periods can inspire enormous creativity or they can be the death of creativity. In the Jaffna peninsula, in the late seventies and early eighties, war and its disruptions produced a new Tamil literature of great vitality, making powerful poetry out of the terror and horror that suddenly overwhelmed ordinary civilian life. It was a poetry of protest, fired by an intense emotional commitment to a cause. The very tensions inherent in the situation inspired and enriched the poetry. I . A similar efflorescence occurred in Sinhala poetry in the seventies, especially the period immediately following the 1971 insurrection. The work of writers like Mahagama Sekera, Parakrama Kodituwakku, Monica Ruwanpathirana, Dharmasiri Rajapakse, Sunil Ariyaratne, Buddhadasa Galappatthy and others brought new life and gave a new direction to Sinhala poetry. 2 It too was a poetry of political commitment, but the emotional intensity of the writing gave it a particular energy that lifted it beyond the merely didactic. By the late eighties this energy seems to have dissipated. As the violence became more intense and widespread, and the issues got ever murkier, and as people no longer had any clear sense of whom or what cause to support, literary writing too seems to have dried Up.3 Those writers who were prolific in the seventies and in the forefront of literary activity were hardly heard of by the late eighties. Of the older generation of writers, Gunadasa Amerasekera continued to write, but his work got increasingly strident and polemical. -

William Congreve. (4) Sidney Grundy

oL12019152-E:r 0112 tue @ 6@D@ EAA@/ Drama and Theatre Note: )k Answer all questions. Total marks for this paper ls 40. )t? In each of the questions I to 40, pick one of the alternatives (l), (2), (3), (4) which you consider is correct or most appropriate. -)v; Mark q,cross (X) on the number corresponding to your choice in the answer sheet provided. )k Further instructions are given on the back of the answer sheet. Follow them carefully. L. Sokari, though comic is basically (1) an exorcistic ceremony. (2) masked entertainment. (3) a fertility rite. (4) social satire. 2. Sokari's husband is (1) the village doctor. (2) Guru Hamy. (3) Punchi Rala. (4) Sottana. 3. Sokari hails from (1) Bengal. (2) Tamil Nadu. (3) Kerala. (4) Uttar Pradesh. 4. The creator of Nurthi was (1) John de Silva. (2) Peter Silva. (3) Don Bastian. (4) Charles Dias. 5. Siri Sangabo (1903) was produced by (1) Don Bastian. (2) John de Silva. (3) Charles Dias. (4) Peter Silva. 6. He Comes from Jaffna (1934), still popular is an adaptation by (1) Dick Dias. (2) V. Ariyaratnam. (3) H. Sri Nissanka. (4) E.F.C. Ludowyk. 7. He Comes from Jaffna was adopted from a play by (1) R.B. Sheridan. (2) Oliver Goldsmith. (3) William Congreve. (4) Sidney Grundy. 8. He still Comes from Jaffna, first staged in Colombo on 13th December 2003, was by (1) Ruana Rajapakshe. (2) Ernest Macintyre. (3) Manuka Wijesinghe. (4) Michael de Soyza. 9. The pioneer in local street drama was (1) Parakrama Niriella. -

Henry Adorned Sri Lankan Theatre, Cinema

Rare Adolf Hitler Smack That: paintings could Work those Lips! Page 2 Page 3 Monday 8th November, 2010 The veteran dramatist married talented actress Manel Ilangakoon in the year 1962. She played the lead role in Jayasena’s drama ‘Kuweni’, for which she won the best actresses award. She started to act just one year after their marriage. She made a very valuable contribution to ‘Hunuwataye Kathawa’ (Caucasian Chalk Circle) playing the main role for 32 years with Jayasena as Azdak. Manel Henry adorned Sri Lankan theatre, cinema Henry by Sunil Thenabadu in the PWD, with his immense innate The veteran dramatist married talented creative ability he was able to produce a actress Manel Ilangakoon in the year 1962. he fi rst death anniversary of number of new plays, the fi rst of which She played the lead role in Jayasena’s legendary dramatist, renowned was ‘Manamalayo’ in the year 1953, then drama ‘Kuweni’, for which she won the best actor, lyricist, translator and ‘Vedagathkama’ in 1954 and ‘Paukarayo’ actresses award. She started to act just author Henry Jayasena falls in1959. Then the vastly improved dramatist one year after their marriage. She made a on Nov. 11, 2010. He can be created ‘Janelaya’ and the famous ‘Kuweni’ very valuable contribution to ‘Hunuwataye bracketedT with eminent literary fi gures who in 1962. Subsequently, he produced ‘Thavath Kathawa’ (Caucasian Chalk Circle) playing adorned the Sri Lankan theatre like Professor Udesanak’, ‘Manaranjana Wedawarjana’, the main role for 32 years with Jayasena as Ediriweera Sarathchandra, Sugathapala De ‘Ahas Maliga’, ‘Hunuwataye Kathawa’, Azdak. Their only son, Sudaraka, during his Silva and Dayananda Gunawardena. -

Report on Public Representations on Constitutional Reform

Report on Public Representations on Constitutional Reform Public Representations Committee on Constitutional Reform May 2016 © Public Representations Committee on Constitutional Reform, May 2016 (Edited & Updated) Public Representations Committee on Constitutional Reform Visumpaya Staple Street Colombo 02 Sri Lanka Acknowledgements As the Chairman I wish to place on record my grateful thanks to all those who took part in the process of carrying out our mandate. Special thanks are due to over two thousand five hundred persons who appeared before us some representing large organizations to make submissions and those who made written representations. It is with deep sense of satisfaction that I place on record my deep gratitude to the Members of the Committee: Mr. S. Winston Pathiraja (Secretary), Mr. Faisz Musthapha, Prof. A. M. Navaratna Bandara, Prof. M. L. A. Cader, Mr. N. Selvakkumaran, Hon. S. Thavarajah, Mr. Kushan D’Alwis, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, Dr.Kumudu Kusum Kumara, Mr. Sunil Jayaratne, Dr.Upul Abeyratne, Mr. Themiya L. B. Hurulle, Mr. S. Vijesandiran, Mr. M. Y. M. Faiz, Mrs. M. K. Nadeeka Damayanthi, Ms.Kanthie Ranasinghe, Mr. S. C. C. Elankovan, and Mr. Sirimasiri Hapuarachchiall of whom dedicated themselves to the enormous task of reaching the people all over the country, getting their views and last but not the least studying their submissions and preparing the report in a very short period of time under trying circumstances, with extremely limited resources, at great sacrifice, in an honorary capacity. How the members of the Committee handled this difficult task needs to be recorded. Visiting twenty five districts within a period of six weeks in itself was an achievement.