1 Anouschka Van Wettum 3788245 BA Thesis English Language And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rezension Im Erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Christoph Oliver Mayer Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Mayer, Christoph Oliver: Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 33 (2016), Nr. 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Attribution 3.0/ License. For more information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Hörfunk und Fernsehen 99 Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC Christine Ehardt, Georg Vogt, Florian Wagner (Hg.): Eurovision Song Contest: Eine kleine Geschichte zwischen Körper, Geschlecht und Nation Wien: Zaglossus 2015, 344 S., ISBN 9783902902320, EUR 19,95 Der Sieg von Conchita Wurst beim Triebel 2011; Goldstein/Taylor 2013) Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) 2014 sowie von einzelnen Wissenschaft- und die sich daran anschließenden ler_innen unterschiedlicher Disziplinen europaweiten Diskussionen um Tole- (z.B. Sieg 2013; Mayer 2015) angesto- ranz und Gleichberechtigung haben ßen wurden. eine ganze Palette von Publikationen Gemeinsam ist all den neueren über den bedeutendsten Populärmusik- Ansätzen ein gesteigertes Interesse für Wettbewerb hervorgerufen (z.B. Wol- Körperinszenierungen, Geschlech- ther/Lackner 2014; Lackner/Rau 2015; terrollen und Nationsbildung, denen Vogel et al. 2015; Kennedy O’Connor sich auch der als „kleine Geschichte“ 2015; Vignoles/O’Brien 2015). Nur untertitelte Sammelband der Wie- wenige wissenschaftliche Monografien ner Medienwissenschaftler_innen (z.B. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Eurovision Song Contest: Lena-Meyer Landrut Verpasst Mit „Taken by a Stranger“ Die Charts-Spitze

09.03.2011 http://www.derwesten.de/nachrichten/Lena-Meyer-Landrut-verpasst-mit-Taken-By-A-Stranger- die-Charts-Spitze-id4397104.html Eurovision Song Contest Lena-Meyer Landrut verpasst mit „Taken By A Stranger“ die Charts-Spitze Nachrichten, 09.03.2011, Ingmar Kreienbrink Lena Meyer-Landrut wird für Deutschland beim Eurovision Song Contest mit dem Song „Taken By A Stranger“ das Projekt Titelverteidigung angehen. (Foto: © Sandra Ludewig / Universal Music 2011) Essen. Die Bilanz ist auf den ersten Blick beeindruckend: Mit fünf Singles aus ihrem neuen Album landete Lena Meyer-Landrut gleichzeitig in den Deutschen Charts. Doch „Taken by a stranger“ - ihr Song für den Eurovision Song Contest - landet hinter „Grenade“ von Bruno Mars „nur“ auf Platz 2. Bei dem vorherigen Medienhype durch die ARD/ProSieben-Kooperations-Sendung „Unser Song für Deutschland“ ist das kleine Überraschung. Schließlich sprang ihr Sieger-Lied „Satellite“ vor einem Jahr ebenso von Null auf 1 wie zahlreiche andere Songs aus anderen Casting-Shows wie etwa „Deutschland sucht den Superstar“ (DSDS). „Mittleres Chart-Fiasko für Plattenfirma Universal“ Jetzt diskutieren die Fans über die Folgen und die Außenwirkung durch die „Schlappe“. Schließlich ist „Taken by a Stranger“ für den Eurovision Song Contest „Unser Song für Deutschland“. In einem Blog ist unter anderem von einem mittleren Chart-Fiasko für die Plattenfirma „Universal“ die Rede. Doch die Gründe für das Ergebnis scheinen wesentlich komplexer. So hat es offenbar in der Startwoche eine Verkaufssperre für den Titel bei wichtigen Downloadshops vom Media Markt, Saturn, MedionMusic und Jamba gegeben. „Download-Verkäufe machen rund 85 Prozent der offiziellen deutschen Single Charts aus“, erläutert Hans Schmucker von media control auf DerWesten-Anfrage. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Identity, Spectacle and Representation: Israeli Entries at the Eurovision

Identity, spectacle and representation: Israeli entries at the Eurovision Song Contest1 Identidad, espectáculo y representación: las candidaturas de Israel en el Festival de la Canción de Eurovisión José Luis Panea holds a Degree in Fine Arts (University of Salamanca, 2013), and has interchange stays at Univer- sity of Lisbon and University of Barcelona. Master’s degree in Art and Visual Practices Research at University of Castilla-La Mancha with End of Studies Special Prize (2014) and Pre-PhD contract in the research project ARES (www.aresvisuals.net). Editor of the volume Secuencias de la experiencia, estadios de lo visible. Aproximaciones al videoarte español 2017) with Ana Martínez-Collado. Aesthetic of Modernity teacher and writer in several re- views especially about his research line ‘Identity politics at the Eurovision Song Contest’. Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, España. [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-8989-9547 Recibido: 01/08/2018 - Aceptado: 14/11/2018 Received: 01/08/2018 - Accepted: 14/11/2018 Abstract: Resumen: Through a sophisticated investment, both capital and symbolic, A partir de una sofisticada inversión, capital y simbólica, el Festival the Eurovision Song Contest generates annually a unique audio- de Eurovisión genera anualmente un espectáculo audiovisual en la ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978 visual spectacle, debating concepts as well as community, televisión pública problematizando conceptos como “comunidad”, Europeanness or cultural identity. Following the recent researches “Europeidad” e “identidad cultural”. Siguiendo las investigaciones re- from the An-glo-Saxon ambit, we will research different editions of cientes en el ámbito anglosajón, recorreremos sus distintas ediciones the show. -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah.. -

Philharmonia Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor

Friday, March 15, 2019, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Philharmonia Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, principal conductor & artistic advisor Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor Truls Mørk, cello Jean SIBELIuS (1865 –1957) e Oceanides (Aallottaret ), Op. 73 Esa-Pekka SALONEN ( b. 1958) Cello Concerto Truls Mørk, cello Ella Wahlström, sound design INTERMISSION Béla BARTóK (1881 –1945) Concerto for Orchestra, BB 123 Introduzione: Andante non troppo – Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegretto scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Pesante – Presto Tour supported by the Philharmonia Foundation and the generous donors to the Philharmonia’s Future 75 Campaign. philharmonia.co.uk Major support for Philharmonia Orchestra’s residency provided by The Bernard Osher Foundation, Patron Sponsors Gail and Dan Rubinfeld, and generous donors to the Matías Tarnopolsky Fund for Cal Performances. Cal Performances’ 2018 –19 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 17a PROGRAM NOTES Jean Sibelius I should never have believed it,” he said.) He was e Oceanides (Aallottaret ), Op. 73 taken to a fashionable New York hotel, where In June 1913, the Helsinki papers reported that his host surprised him with the announcement Jean Sibelius, the brightest ornament of Finnish that Yale university wished to present him culture, had declined an invitation to journey with an honorary doctorate on June 6th in New to America to conduct some of his music, Haven. On the next day, he was taken to the though he did agreed to accept membership Stoeckel’s rural Connecticut mansion, which in the National Music Society and provide the Sibelius described as a “wonderful estate among publishing house of Silver Burdett with ree wooded hills, intersected by rivers and shim - Songs for American School Children . -

Professtonal~' , : Wor~ ~:" Ki" :~!G!

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. 2olsa~ ....... ,., ..~,.,~,,.,.., (~Cj;o~r3) Model Treatment aria Services Ap ~roa¢.nes }or. Men~HOaith; Professtonal~' , : Wor~~:" ki" :~!g!::::: #ith Fam~ities~: g Family Abducted Ch~i~(dren ratntng Manuat THE WESTERN CENTERFORCHILD PROTECTION . SUBMITTED TO U.S. Dep~irtment 0f Justice - Office of Justice Programs - office6fjuveni[e Justice and DelinquencJ~,Prevention Model Treatment and Services Approaches for Professionals Working with " " Families of Family Abducted Children Treatment Manual~ Western Center for Child Protection Reno, Nevada JoAnn Behrman-Lippert, Ph.D. Director and Prinicipal:Investigat0r University of California, San Francisco Center for the Study of Trauma Chris Hatcher, Ph.D. Associate Investigator The Model Treatment Services and Approaches for Mental Health Professionals Working With Families of Missing Children was supported by the Agreement Number 93-MC-CX- 0003 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U. S. Department of ~ Justice. Points of view or opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U. S. Department. of Justice. Acknowledgments The authors wish to acknowledge the advice, support and assistance of all involved. Not listed here are the names of the mental health professionals, recovered children and parents who shared their experiences and made this training manual possible. We extend special thanks to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and to Didi Hirsch Community Mental Health Center for their support by making it possible to field test and extend the model and make this project a success. -

Lena and ESC Representatives Praise Audience Choice

Presse / 2011 / "An excellent choice!": Lena and ESC representatives praise audience choice 'Taken by a stranger' is the title of the song which Lena will perform on May 14th at the Eurovision Song Contest 2011 in Düsseldorf. The winning song won over the audience on Friday (February 18th) in the final of the show 'Our Song for Germany' which was aired live on Das Erste. The winning song was way out in front of the other five songs that made it into the final. The synth- driven electro-pop song was written by Nicole Morier, Gus Seyffert and Monica Birkenes. 'Taken by a stranger' is the title of the song which Lena will perform on May 14th at the Eurovision Song Contest 2011 in Düsseldorf. The winning song won over the audience on Friday (February 18th) in the final of the show 'Our Song for Germany' which was aired live on Das Erste. The winning song was way out in front of the other five songs that made it into the final. The synth- driven electro-pop song was written by Nicole Morier, Gus Seyffert and Monica Birkenes. An average of 3.25 million viewers followed the whole of 'Our Song for Germany' (market share: 10.1 percent). 12.42 million tuned in for at least one minute. Among the 14 - 29 year old age group, the average market share was 12.0 percent, meaning that Das Erste achieved a viewer quote almost twice as high as their average for Friday primetime. The market share among 14 to 49 years olds was 11.5 percent (1.41 million). -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke Eurovision Karaoke 2 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA AUS 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ALB 07 Hear My Plea BELGÍA ALB 10 It's All About You BEL 06 Je t'adore ALB 12 Suus BEL 12 Would You? ALB 13 Identitet BEL 86 J'aime la vie ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger BEL 87 Soldiers of love BEL 89 Door de wind BEL 98 Dis oui ARMENÍA ARM 07 Anytime you need BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA ARM 08 Qele Qele BOS 99 Putnici ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) BOS 06 Lejla ARM 10 Apricot Stone BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena ARM 11 Boom Boom ARM 13 Lonely Planet ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone BOS 11 Love In Rewind BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam ASERBAÍDSJAN AZE 08 Day after day BRETLAND AZE 09 Always UKI 83 I'm never giving up AZE 14 Start The Fire UKI 96 Ooh aah... just a little bit UKI 04 Hold onto our love AUSTURRÍKI UKI 07 Flying the flag (for you) AUS 89 Nur ein Lied UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me AUS 90 Keine Mauern mehr UKI 11 I Can AUS 04 Du bist UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free AUS 07 Get a life - get alive UKI 13 Believe in Me AUS 11 The Secret Is Love UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe AUS 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUS 13 Shine 3 Eurovision Karaoke BÚLGARÍA FIN 13 Marry Me BUL 05 Lorraine FIN 84 Hengaillaan BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited FRAKKLAND BUL 13 Samo Shampioni FRA 69 Un jour, un enfant DANMÖRK FRA 93 Mama Corsica DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love FRA 03 Monts et merveilles DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen DEN 10 New Tomorrow FRA 09 Et S'il Fallait Le Faire DEN 12 Should've Known Better FRA 11 Sognu DEN 13 Only Teardrops -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

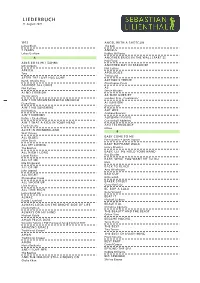

Sebastian Lilienthal

LIEDERBUCH 11. August 2021 1973 ANGEL WITH A SHOTGUN James Blunt The Cab 7 YEARS ANGELS Lukas Graham Robbie Williams A ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL [PART 2] Pink Floyd ABER BITTE MIT SAHNE Udo Jürgens ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE Phil Collins AFRICA Toto APOLOGIZE Timbaland AFTER THE LOVE HAS GONE Earth, Wind & Fire ARTHUR’S THEME Christopher Cross AGAINST ALL ODDS Phil Collins AS Stevie Wonder AI NO CORRIDA Quincy Jones AS TIME GOES BY aus dem Film „Casablanca“ AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH Diana Ross ATTENTION Charlie Puth AIN’T NO SUNSHINE Bill Withers AUF UNS Andreas Bourani AIN’T NOBODY Rufus + Chaka Khan AUTUMN LEAVES Cannonball Adderley AIN’T THAT A KICK IN YOUR HEAD Frank Sinatra AYO TECHNOLOGY Milow ALICE IN WONDERLAND B Walt Disney ALL BLUES BABY COME TO ME Miles Davis Patti Austin + James Ingram ALL MY LOVING BABY ELEPHANT WALK The Beatles Henry Mancini ALL NIGHT LONG BABY, LET ME HOLD YOUR HAND Lionel Richie Ray Charles ALL OF ME BABY, WHAT YOU WANT ME TO DO Ella Fitzgerald Elvis ALL OF ME BACK TO BLACK John Legend Amy Winehouse ALL RIGHT BAD GUY Christopher Cross Billie Eilish ALL SHOOK UP BAKER STREET Elvis Presley Gerry Rafferty ALL TIME HIGH BE-BOP-A-LULA James Bond 007 Gene Vincent ALMAZ BEAT IT Randy Crawford Michael Jackson ALWAYS LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE OF LIFE BEAUTIFUL Monty Python Christina Aguilera ALWAYS ON MY MIND THE BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Michael Bublé Celine Dion AMAR PELOS DOIS BESAME MUCHO Salvador Sobral / ESC European Song Contest 2017 Tania Maria AMAZING GRACE THE BEST Traditional Gospel Tina Turner AMEN THE BEST