05. the Dance of Shiva.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Programmable Models for Graphics Engines (High

Hello and welcome! Today I want to talk about the evolution of programmable models for graphics engine programming for algorithm developing My name is Natalya Tatarchuk (some folks know me as Natasha) and I am director of global graphics at Unity I recently joined Unity… 4 …right after having helped ship the original Destiny @ Bungie where I was the graphics lead and engineering architect … 5 and lead the graphics team for Destiny 2, shipping this year. Before that, I led the graphics research and demo team @ AMD, helping drive and define graphics API such as DirectX 11 and define GPU hardware features together with the architecture team. Oh, and I developed a bunch of graphics algorithms and demos when I was there too. At Unity, I am helping to define a vision for the future of Graphics and help drive the graphics technology forward. I am lucky because I get to do it with an amazing team of really talented folks working on graphics at Unity! In today’s talk I want to touch on the programming models we use for real-time graphics, and how we could possibly improve things. As all in the room will easily agree, what we currently have as programming models for graphics engineering are rather complex beasts. We have numerous dimensions in that domain: Model graphics programming lives on top of a very fragmented and complex platform and API ecosystem For example, this is snapshot of all the more than 25 platforms that Unity supports today, including PC, consoles, VR, mobile platforms – all with varied hardware, divergent graphics API and feature sets. -

The Science Behind Sandhya Vandanam

|| 1 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 Sri Vaidya Veeraraghavan – Nacchiyar Thirukkolam - Thiruevvul 2 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 �ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || Sri Nrisimha Priya ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ AN AU T H O R I S E D PU B L I C A T I O N OF SR I AH O B I L A M A T H A M H. H. 45th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham H.H. 46th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham Founder Sri Nrisimhapriya (E) H.H. Sri Lakshminrisimha H.H. Srivan Sathakopa Divya Paduka Sevaka Srivan Sathakopa Sri Ranganatha Yatindra Mahadesikan Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikan Ahobile Garudasaila madhye The English edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya not only krpavasat kalpita sannidhanam / brings to its readers the wisdom of Vaishnavite Lakshmya samalingita vama bhagam tenets every month, but also serves as a link LakshmiNrsimham Saranam prapadye // between Sri Matham and its disciples. We confer Narayana yatindrasya krpaya'ngilaraginam / our benediction upon Sri Nrisimhapriya (English) Sukhabodhaya tattvanam patrikeyam prakasyate // for achieving a spectacular increase in readership SriNrsimhapriya hyesha pratigeham sada vaset / and for its readers to acquire spiritual wisdom Pathithranam ca lokanam karotu Nrharirhitam // and enlightenment. It would give us pleasure to see all devotees patronize this spiritual journal by The English Monthly Edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya is becoming subscribers. being published for the benefit of those who are better placed to understand the Vedantic truths through the medium of English. May this magazine have a glorious growth and shine in the homes of the countless devotees of Lord Sri Lakshmi Nrisimha! May the Lord shower His benign blessings on all those who read it! 3 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 4 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || CONTENTS Sri Nrisimha Priya Owner: Panchanga Sangraham 6 H.H. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration Using Game Engines and VR on EOSC

Novel EOSC services for Emerging Atmosphere, Underwater and Space Challenges 2020 October Cloud-Based Visual Discovery in Astronomy: Big Data Exploration using Game Engines and VR on EOSC Game engines are continuously evolving toolkits that assist in communicating with underlying frameworks and APIs for rendering, audio and interfacing. A game engine core functionality is its collection of libraries and user interface used to assist a developer in creating an artifact that can render and play sounds seamlessly, while handling collisions, updating physics, and processing AI and player inputs in a live and continuous looping mechanism. Game engines support scripting functionality through, e.g. C# in Unity [1] and Blueprints in Unreal, making them accessible to wide audiences of non-specialists. Some game companies modify engines for a game until they become bespoke, e.g. the creation of star citizen [3] which was being created using Amazon’s Lumebryard [4] until the game engine was modified enough for them to claim it as the bespoke “Star Engine”. On the opposite side of the spectrum, a game engine such as Frostbite [5] which specialised in dynamic destruction, bipedal first person animation and online multiplayer, was refactored into a versatile engine used for many different types of games [6]. Currently, there are over 100 game engines (see examples in Figure 1a). Game engines can be classified in a variety of ways, e.g. [7] outlines criteria based on requirements for knowledge of programming, reliance on popular web technologies, accessibility in terms of open source software and user customisation and deployment in professional settings. -

Moving from Unity to Godot an In-Depth Handbook to Godot for Unity Users

Moving from Unity to Godot An In-Depth Handbook to Godot for Unity Users Alan Thorn Moving from Unity to Godot: An In-Depth Handbook to Godot for Unity Users Alan Thorn High Wycombe, UK ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4842-5907-8 ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4842-5908-5 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-5908-5 Copyright © 2020 by Alan Thorn This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Trademarked names, logos, and images may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, logo, or image we use the names, logos, and images only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. -

Samskruti Newsletter Dec 2016

December Dec 2016 Calendar Refining Young Minds 19th-25th Deiva Tamizh Isai Vizha SAMSKRUTI 24th Madhurageetham Festival Audition Round Our Master’s Voice For more info visit Dr A Bhagyanathan www.namadwaar.org MENTAL STRENGTH ..contd Recent researchers say that even when the baby is in the mother's womb, it listens to what's going on. That's why the What’s Inside mother is advised to listen to fine music. This is not something that wasn't known to our ancestors because when Baktha Prahlad was in his mother's womb, that was when he received the Nama, the upadesha from his Guru Chaitanya and he started at that point itself. It's something that was Mahaprabhu 3 established in our puranas from time immemorial, which has been scientifically proven today too. So, the knowledge gain starts from that point and from the moment the baby is Ramayana… born it continues. The baby learns from everything it sees 4 and hears and interacts with. It is a continuous learning As I See It process. And then, it learns it's first words- the alphabet, the parents, the mother, the father- they teach the baby and then he's put into school, kindergarten. Then he goes Padaleeshwarar through primary school. Then he finishes high school, at Temple 5 which point he decides his choice, his career path. And then, he goes into university - the learning continues. Intellectual strengthening continues. It's a continuous process from day As It 1, it keeps happening at different levels. Then he lands 6 himself a nice job. -

Game Engine Review

Game Engine Review Mr. Stuart Armstrong 12565 Research Parkway, Suite 350 Orlando FL, 32826 USA [email protected] ABSTRACT There has been a significant amount of interest around the use of Commercial Off The Shelf products to support military training and education. This paper compares a number of current game engines available on the market and assesses them against potential military simulation criteria. 1.0 GAMES IN DEFENSE “A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, which result in a quantifiable outcome.” The use of games for defence simulation can be broadly split into two categories – the use of game technologies to provide an immersive and flexible military training system and a “serious game” that uses game design principles (such as narrative and scoring) to deliver education and training content in a novel way. This talk and subsequent education notes focus on the use of game technologies, in particular game engines to support military training. 2.0 INTRODUCTION TO GAMES ENGINES “A games engine is a software suite designed to facilitate the production of computer games.” Developers use games engines to create games for games consoles, personal computers and growingly mobile devices. Games engines provide a flexible and reusable development toolkit with all the core functionality required to produce a game quickly and efficiently. Multiple games can be produced from the same games engine, for example Counter Strike Source, Half Life 2 and Left 4 Dead 2 are all created using the Source engine. Equally once created, the game source code can with little, if any modification be abstracted for different gaming platforms such as a Playstation, Personal Computer or Wii. -

Game Engines in Game Education

Game Engines in Game Education: Thinking Inside the Tool Box? sebastian deterding, university of york casey o’donnell, michigan state university [1] rise of the machines why care about game engines? unity at gdc 2009 unity at gdc 2015 what engines do your students use? Unity 3D 100% Unreal 73% GameMaker 38% Construct2 19% HaxeFlixel 15% Undergraduate Programs with Students Using a Particular Engine (n=30) what engines do programs provide instruction for? Unity 3D 92% Unreal 54% GameMaker 15% Construct2 19% HaxeFlixel, CryEngine 8% undergraduate Programs with Explicit Instruction for an Engine (n=30) make our stats better! http://bit.ly/ hevga_engine_survey [02] machines of loving grace just what is it that makes today’s game engines so different, so appealing? how sought-after is experience with game engines by game companies hiring your graduates? Always 33% Frequently 33% Regularly 26.67% Rarely 6.67% Not at all 0% universities offering an Undergraduate Program (n=30) how will industry demand evolve in the next 5 years? increase strongly 33% increase somewhat 43% stay as it is 20% decrease somewhat 3% decrease strongly 0% universities offering an Undergraduate Program (n=30) advantages of game engines • “Employability!” They fit industry needs, especially for indies • They free up time spent on low-level programming for learning and doing game and level design, polish • Students build a portfolio of more and more polished games • They let everyone prototype quickly • They allow buildup and transfer of a defined skill, learning how disciplines work together along pipelines • One tool for all classes is easier to teach, run, and service “Our Unification of Thoughts is more powerful a weapon than any fleet or army on earth.” [03] the machine stops issues – and solutions 1. -

Magical Creatures in Isadora Moon

The Magical Creatures of Isadora Moon In the Isadora Moon stories, Isadora’s mum is a fairy and her dad is a vampire. This means that, even though Isadora lives in the human world, she has adventures with lots of fantastical creatures. Harriet Muncaster writes and draws the Isadora Moon books. Writers like Harriet often look at stories and legends from the past to get ideas for their own stories. What are some of the legends that Harriet looked at when telling the story of Isadora Moon, and what has she changed to make her stories as unique as Isadora herself? Fairies In the modern day, we picture fairies as tiny human-like creatures with wings like those of dragonflies or butterflies. However, up until the Victorian age (1837- 1901), the word ‘fairy’ meant any magical creature or events and comes from the Old French word faerie, which means ‘enchanted’. Goblins, pixies, dwarves and nymphs were all called ‘fairies’. These different types of fairies usually did not have wings, and were sometimes human- sized instead of tiny. They could also be good or bad, either helping or tricking people. Luckily, Isadora’s mum, Countess Cordelia Moon, is a good fairy, who likes baking magical cakes, planting colourful flowers, and spending time in nature. Like most modern fairies, she has wings, magical powers, and a close connection with nature, but unlike fairies in some stories, she is human-size. Isadora’s mum can fly using her fairy wings and can use her magic wand to bring toys to life, make plants grow anywhere, and change the appearance of different objects, such as Isadora’s tent. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

A New Year's Greetin

THE 8ID0HANTA DEEPIKA OR The Light of Truth. A Monthly Journal, Devoted to ReligioM, Philosophy^ Littrat%tt\ Scknu 6<. •n tlM qummn'u CoflUMmonUiaii Dkj, IMT, VolVn APRIL 1906 No I A NEW YEAR'S GREETIN This Agaval is by a minstrel, known to us as Kanyan or *'Singer' of the flowery hill, who was a court poet and friend of Ko Pferum Coran of Urraiyur—a little, it may be, before the data of the Kurral. See Purra Nannurru 67, 191, 192, 212. mekjuu^ tSpa-^ir €Uirjnr;^ QKirft£fiLti ^ea^^^ti ^eu^Qt^ir ^csr«r:—^ Si^O/fmr LuS^^jfuh SjtoQut;—Qp^Mr fill^DHAKTA DKKPTKA, euTssrii ^^a^Slaff? lu/r^^i sisoQuTQ^ Lpei>ei€0 Qu.iturfpjM li/rsuyS^u u(B^Ui i^dsasrQuir^ ^tsST (ipsnpsuij^u zjCFe-ii) gtcstu^ ^p(peo/r/r QuiPiQfUir^ff tSoj^^Sfiiii -r- THE SAGES. To lis all toAvns arc one, all men our kin. Life's gooi comes not from others' gift, nor ill Man s pains and pains' relief ?.re from within. Death s no new thing; nor do our bosoms thrill When joyous life seems like a luscious draught. AVhen grieved, y\c patient suffer; for, we deem This much-praised life of ours a fragile raft Borne dowii tiie waters of some mountain stream That o'er Jiuge bouldere roaring seeks the plain. Tho' storms Avith lightnings' ilash from darken d skica Descend, tho raft goes on as fates ordain. Thus have we seen in visions of the wsc!— We marvel Jiiot at greatness of tlie great; Still less despise we men of low estate. -

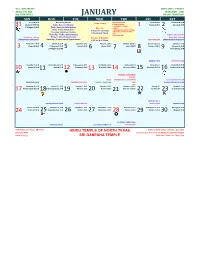

Temple Calendar

Year : SHAARVARI MARGASIRA - PUSHYA Ayana: UTTARA MARGAZHI - THAI Rtu: HEMANTHA JANUARY DHANU - MAKARAM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Tritiya 8.54 D Recurring Events Special Events Tritiya 9.40 N Chaturthi 8.52 N Temple Hours Chaturthi 6.55 ND Daily: Ganesha Homam 01 NEW YEAR DAY Pushya 8.45 D Aslesha 8.47 D 31 12 HANUMAN JAYANTHI 1 2 P Phalguni 1.48 D Daily: Ganesha Abhishekam Mon - Fri 13 BHOGI Daily: Shiva Abhishekam 14 MAKARA SANKRANTHI/PONGAL 9:30 am to 12:30 pm Tuesday: Hanuman Chalisa 14 MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm PUJA Thursday : Vishnu Sahasranama 28 THAI POOSAM VENKATESWARA PUJA Friday: Lalitha Sahasranama Moon Rise 9.14 pm Sat, Sun & Holidays Moon Rise 9.13 pm Saturday: Venkateswara Suprabhatam SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI 8:30 am to 8:30 pm NEW YEAR DAY SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI Panchami 7.44 N Shashti 6.17 N Saptami 4.34 D Ashtami 2.36 D Navami 12.28 D Dasami 10.10 D Ekadasi 7.47 D Magha 8.26 D P Phalguni 7.47 D Hasta 5.39 N Chitra 4.16 N Swati 2.42 N Vishaka 1.02 N Dwadasi 5.23 N 3 4 U Phalguni 6.50 ND 5 6 7 8 9 Anuradha 11.19 N EKADASI PUJA AYYAPPAN PUJA Trayodasi 3.02 N Chaturdasi 12.52 N Amavasya 11.00 N Prathama 9.31 N Dwitiya 8.35 N Tritiya 8.15 N Chaturthi 8.38 N 10 Jyeshta 9.39 N 11 Mula 8.07 N 12 P Ashada 6.51 N 13 U Ashada 5.58 D 14 Shravana 5.34 D 15 Dhanishta 5.47 D 16 Satabhisha 6.39 N MAKARA SANKRANTHI PONGAL BHOGI MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN SRINIVASA KALYANAM PRADOSHA PUJA HANUMAN JAYANTHI PUSHYA / MAKARAM PUJA SHUKLA CHATURTHI PUJA THAI Panchami 9.44 N Shashti 11.29 N Saptami 1.45 N Ashtami 4.20 N Navami 6.59