Growing Pains in the Colonies Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rupert's Land and North-West Territory Order

Rupert's Land and North-Western Territory Order (Order of Her Majesty in Council Admitting Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory into the Union) At the Court at Windsor, the 23rd day of June, 1870 PRESENT, The Queen's Most Excellent Majesty Lord President Lord Privy Seal Lord Chamberlain Mr. Gladstone Whereas by the "Constitution Act, 1867," it was (amongst other things) enacted that it should be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice or Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, on Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, to admit Rupert's Land and the North- Western Territory, or either of them, into the Union on such terms and conditions in each case as should be in the Addresses expressed, and as the Queen should think fit to approve, subject to the provisions of the said Act. And it was further enacted that the provisions of any Order in Council in that behalf should have effect as if they had been enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland: And whereas by an Address from the Houses of the Parliament of Canada, of which Address a copy is contained in the Schedule to this Order annexed, marked A, Her Majesty was prayed, by and with the advice of Her Most Honourable Privy Council, to unite Rupert's Land and the NorthWestern Territory with the Dominion of Canada, and to grant to the Parliament of Canada authority to legislate for their future welfare and good government upon the terms and conditions therein stated. -

The Indian Trade War Reconsidered: Morris on Ivers

Larry E. Ivers. This Torrent of Indians: War on the Southern Frontier, 1715-1728. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016. 292 pp. $24.95, paper, ISBN 978-1-61117-606-3. Reviewed by Michael Morris Published on H-SC (September, 2016) Commissioned by David W. Dangerfield (University of South Carolina - Salkehatchie) If South Carolina’s Yamasee War is ever given tribes and forgotten forts. His secondary works a subtitle, it could rightly be called the Great Indi‐ run the gamut from Verner Crane's 1959 classic, an Trade War. Larry Ivers, a lawyer by training The Southern Frontier to William Ramsey's 2008 with a military background, notes in his preface work, The Yamasee War. that his intent was to fll a void in the history of The frst three chapters set the stage for con‐ the Yamasee War and to provide a more detailed flict by discussing the Indian agents and traders analysis of the military operations of the war. To who caused the crisis by enslavement of debtor that end, he clearly succeeds in recreating the sto‐ Indians, and one of its strengths is naming people ry of a colony at war aggravated by professional who are otherwise shadowy fgures in backcoun‐ Indian traders who trafficked in Indian slaves to try history. The Yamasee leadership clearly pay their debts. Ivers reveals an incredibly de‐ warned traders Samuel Warner and William Bray tailed account of the debacle and this detailed of a planned murder of all traders and an attack analysis is both a major strength and a minor on the colony if the South Carolina government weakness of the work. -

A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine Andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation White, andrea Paige, "Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626354. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-whwd-r651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIVING ON THE PERIPHERY: A STUDY OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY YAMASEE MISSION COMMUNITY IN COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Andrea P. White 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of aster of Arts Author Approved, November 2002 n / i i WJ m Norman Barka Carl Halbirt City Archaeologist, St. Augustine, FL Theodore Reinhart TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 2 Creolization Models in Historical Archaeology 4 Previous Archaeological Work on the Yamasee and Significance of La Punta 7 PROJECT METHODS 10 Historical Sources 10 Research Design and The City of St. -

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1. The system of indentured labor used during the Colonial period had which of the following effects? A. It enabled England to deport most criminals. B. It enabled poor people to seek opportunity in America. C. It delayed the establishment of slavery in the South until about 1750. D. It facilitated the cultivation of cotton in the South. E. It instituted social equality. 2. Indentured servants were usually A. slaves who had been emancipated by their masters B. free blacks forced to sell themselves into slavery by economic conditions. C. paroled prisoners bound to a lifetime of service in the colonies D. persons who voluntarily bound themselves to labor for a set number of years in return for transportation in the colonies. E. the sons and daughters of slaves. 3. The headright system adopted in the Virginia colony A. determined the eligibility of a settler for voting and holding office. B. toughened the laws applying to indentured servants. C. gave 50 acres of land to anyone who would transport himself to the colony. D. encouraged the development of urban centers. E. prohibited the settlement of single men and women in the colony. 4. Of the African slaves brought to the New World by Europeans from 1492 through 1770, the vast majority were shipped to A Virginia B the Carolinas C the Caribbean D Georgia E Florida 5. A majority of the early English migrants to the Chesapeake were A. Families with young children B. Indentured servants C. Wealthy gentlemen D. Merchants and craftsmen E. -

Life in the Colonies

CHAPTER 4 Life in the Colonies 4.1 Introduction n 1723, a tired teenager stepped off a boat onto Philadelphia’s Market Street wharf. He was an odd-looking sight. Not having luggage, he had I stuffed his pockets with extra clothes. The young man followed a group of “clean dressed people” into a Quaker meeting house, where he soon fell asleep. The sleeping teenager with the lumpy clothes was Benjamin Franklin. Recently, he had run away from his brother James’s print shop in Boston. When he was 12, Franklin had signed a contract to work for his brother for nine years. But after enduring James’s nasty temper for five years, Franklin packed his pockets and left. In Philadelphia, Franklin quickly found work as a printer’s assistant. Within a few years, he had saved enough money to open his own print shop. His first success was a newspaper called the Pennsylvania Gazette. In 1732, readers of the Gazette saw an advertisement for Poor Richard’s Almanac. An almanac is a book, published annually, that contains information about weather predictions, the times of sunrises and sunsets, planting advice for farmers, and other useful subjects. According to the advertisement, Poor Richard’s Almanac was written by “Richard Saunders” and printed by “B. Franklin.” Nobody knew then that the author and printer were actually the same person. In addition to the usual information contained in almanacs, Franklin mixed in some proverbs, or wise sayings. Several of them are still remembered today. Here are three of the best- known: “A penny saved is a penny earned.” “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” “Fish and visitors smell in three days.” Poor Richard’s Almanac sold so well that Franklin was able to retire at age 42. -

21 Lc 44 1700S H. B. 647 (Sub)

21 LC 44 1700S House Bill 647 (COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE) By: Representatives Smith of the 133rd, Smith of the 70th, Washburn of the 141st, Williams of the 145th, and Dickey of the 140th A BILL TO BE ENTITLED AN ACT 1 To amend Part 1 of Article 2 of Chapter 8 of Title 12 of the Official Code of Georgia 2 Annotated, relating to general provisions relative to solid waste management, so as to 3 provide for post-closure ground-water monitoring at closed coal combustion residual 4 impoundments; to provide for definitions; to provide for ground-water monitoring reports; 5 to amend Part 3 of Article 2 of Chapter 7 of Title 16 of the Official Code of Georgia 6 Annotated, relating to criminal trespass and damage to property relative to waste control, so 7 as to provide for a conforming cross-reference; to amend Part 1 of Article 3 of Chapter 8 of 8 Title 48 of the Official Code of Georgia Annotated, relating to county special purpose local 9 option sales tax, so as to provide for conforming cross-references; to provide for related 10 matters; to repeal conflicting laws; and for other purposes. 11 BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF GEORGIA: 12 SECTION 1. 13 Part 1 of Article 2 of Chapter 8 of Title 12 of the Official Code of Georgia Annotated, 14 relating to general provisions relative to solid waste management, is amended in Code 15 Section 12-8-22, relating to definitions, by adding new paragraphs and renumbering existing 16 paragraphs to read as follows: H. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

PELLIZZARI-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (3.679Mb)

A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pellizzari, Peter. 2020. A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365752 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 A dissertation presented by Peter Pellizzari to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2020 © 2020 Peter Pellizzari All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Jane Kamensky and Jill Lepore Peter Pellizzari A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 Abstract The American Revolution not only marked the end of Britain’s control over thirteen rebellious colonies, but also the beginning of a division among subsequent historians that has long shaped our understanding of British America. Some historians have emphasized a continental approach and believe research should look west, toward the people that inhabited places outside the traditional “thirteen colonies” that would become the United States, such as the Gulf Coast or the Great Lakes region. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

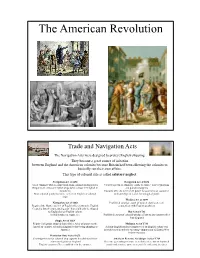

The American Revolution Presentation

The American Revolution Trade and Navigation Acts The Navigation Acts were designed to protect English shipping. ! They became a great source of irritation between England and the American colonies because Britain had been allowing the colonies to basically run their own affairs. ! This type of colonial rule is called salutary neglect. Navigation Act of 1651 Navigation Act of 1696 Goal: eliminate Dutch competition from colonial trading routes Created system of admiralty courts to enforce trade regulations Required all crews on English ships to be at least 1/2 English in and punish smugglers nationality Customs officials were given power to issue writs of assistance Most colonial goods had to be carried on English or colonial to board ships to search for smuggled goods ships ! ! Woolens Act of 1699 Navigation Act of 1660 Prohibited colonial export of woolen cloth to prevent Required the Master and 3/4 of English ship crews to be English competition with English producers Created a list of "enumerated goods” that could only be shipped ! to England or an English colony Hat Act of 1732 included tobacco, sugar, rice Prohibited export of colonial-produced hats to any country other ! than England Staple Act of 1663 ! Required all goods shipped from Africa, Asia, or Europe to the Molasses Act of 1733 American colonies to land in England before being shipping to All non-English molasses imported to an English colony was America heavily taxed in order to encourage importation of British West ! Indian molasses Plantation Duty Act of 1673 ! Created -

An Educator's Guide to the Story of North Carolina

Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide An Educator’s Guide to The Story of North Carolina An exhibition content guide for teachers covering the major themes and subject areas of the museum’s exhibition The Story of North Carolina. Use this guide to help create lesson plans, plan a field trip, and generate pre- and post-visit activities. This guide contains recommended lessons by the UNC Civic Education Consortium (available at http://database.civics.unc.edu/), inquiries aligned to the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and links to related primary sources available in the Library of Congress. Updated Fall 2016 1 Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide The earth was formed about 4,500 million years (4.5 billion years) ago. The landmass under North Carolina began to form about 1,700 million years ago, and has been in constant change ever since. Continents broke apart, merged, then drifted apart again. After North Carolina found its present place on the eastern coast of North America, the global climate warmed and cooled many times. The first single-celled life-forms appeared as early as 3,800 million years ago. As life-forms grew more complex, they diversified. Plants and animals became distinct. Gradually life crept out from the oceans and took over the land. The ancestors of humans began to walk upright only a few million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, emerged only about 120,000 years ago. The first humans arrived in North Carolina approximately 14,000 years ago—and continued the process of environmental change through hunting, agriculture, and eventually development. -

18Th Century Rural Architecture ROOTED in SWEDEN Guest Article

no 8 2010-01 ROOTED IN SWEDEN Living in Swedeland USA 18th Century Rural Architecture Guest Article Emigration Conference | SwedGen Tour 2009 contents 18th Century Rural 3 Architecture - Skåne Emigration Conference - 7 “Letters to Sweden” Living in Swedeland USA 9 7 16 8 The Digital Race 13 Swedgen Tour 2009 14 Christmas as Celebrated 16 9 in my Childhood Swedish Genealogical 20 Society of Minnesota 3 firstly... …I would like to talk about the cur- rent status of genealogy. A while ago I spoke to a fellow genealogist who experiences problems in getting local government funding for genealogical societies and events. This person felt 20 that the cultural funding tended to fa- vour sports activities for the young, Along with genealogy comes inevita- ter at night long after the rest of the and that it might even be a question of bly a curiosity about how people lived family has gone to bed. At the same age discrimination since genealogy is and a general historical curiosity, not time it can be very social and also a regarded as an “old folks” activity. I about kings and queens and wars and team effort. You can save yourself a don’t know the full specifics or even revolutions, but about the little man. lot of work by connecting with other if this is the typical case, but I still To me, this history is equally excit- genealogists, by exchanging infor- felt like I had taken a blow to the sto- ing and more or less skipped during mation and tips of resources.