The University of Michigan ,,,, H Transportation Research Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powerpc and Power Macintosh L Technical Information

L Technical PowerPC and Information Power Macintosh Recently, both Apple Computer and IBM have introduced products based on the PowerPC™ microprocessor. The PowerPC microprocessor is a result of collaboration between three industry leaders: Apple, IBM, and Motorola. This cooperative project was announced in 1991. The project’s goal was to advance the evolution of the personal computer in five major areas: • PowerPC – Apple, IBM, and Motorola agreed to develop a family of RISC microprocessors. • Interoperability – IBM and Apple agreed to work together to ensure that Macintosh® computers work smoothly with large, networked IBM enterprise systems. This involves products in networking and communication. • PowerOpen® – IBM and Apple agreed to co-develop a new version of the UNIX® operating system that takes advantage of the strengths of the PowerPC microprocessor. • Kaleida – A new company called Kaleida was created to work on new standards for multimedia products. • Taligent – A new company called Taligent was created to develop an object-oriented operating system. While there have been advances in all of these areas, the announcement of the Power Macintosh has focused industry attention on the PowerPC chip. (Note: Microprocessors are often referred to as ‘chips’ or ‘computer chips’.) The PowerPC microprocessor The term PowerPC describes a family of microprocessors that may be used in a variety of computers. Apple Computer has introduced a series of computers based on this microprocessor which they will call Power Macintoshes™. IBM computers that contain the PowerPC microprocessor will be part of the RS6000 series. The RS6000 series is a high-end UNIX product. The Power Macintosh, on the other hand, is intended as a broad- based consumer product. -

Macintosh Quadra 840AV K Service Source

K Service Source Macintosh Quadra 840AV K Service Source Specifications Macintosh Quadra 840AV Specifications Processor - 1 Processor CPU Motorola 68040 microprocessor 40 MHz Built-in paged memory management unit (PMMU), floating-point unit (FPU), and 8K memory cache Addressing 32-bit registers 32-bit address/data bus Direct Memory A Peripheral Subsystem Controller (PSC) provides direct Access (DMA) memory access (DMA) between the 68040 buses and peripheral devices. Specifications Processor - 2 Digital Signal AT&T DSP3210 32-bit floating-point digital signal processor Processor (DSP) Supports real-time tasks such as speech recognition, audio compression, and analog modem signal processing. Specifications Memory - 3 Memory RAM 8 MB standard (one 8 MB SIMM), expandable to 128 MB 72-pin SIMMs Requires CAS-before-RAS 60 ns access time ROM 2 MB soldered on logic board PRAM 256 bytes of parameter memory Specifications Memory - 4 VRAM 1 MB standard, expandable to 2 MB (80 ns or faster 256K VRAM SIMMs) Maximum pixel depths for 1 MB / 2 MB VRAM: 12-inch color (512 x 384) - 16 / 16 bits per pixel 12-inch monochrome (640 x 480) - 16 / 16 bits per pixel 13-inch color (640 x 480) - 8 / 16 bits per pixel 15-inch portrait (640 x 870) - 4 / 8 bits per pixel 16-inch color (832 x 624) - 8 / 16 bits per pixel 19-inch color (1024 x 768) - 4 / 8 bits per pixel 21-inch monochrome (1152 x 870) - 4 / 8 bits per pixel 21-inch color (1152 x 870) - 4 / 8 bits per pixel VGA (640 x 480) - 8 / 16 bits per pixel SVGA (800 x 600) - 8 / 16 bits per pixel Clock/Calendar Apple custom chip with long-life lithium battery Specifications Disk Storage - 5 Disk Storage Floppy Drive Internal, 1.4 MB Apple SuperDrive Hard Drive Internal, 3.5 in. -

Lnternetting -P

April 1994 $2.95 The Journal of Washington Apple Pi, Ltd. Volume 16, Number 4 lnternetting -p. 9 WordPerfect 3.0-p. 14 ~ Laser Printers -p. 18 Washington Apple Pi General Meeting 4th Saturday • 9:00 a.m. • Burning Tree Elementary School • 7900 Beech Tree Rd. Bethesda, Maryland April 23, 1994 Microsoft: FoxPro May21, 1994 Ares Software Burning• Tree E.S. DATES CHANGE! Bethesda, MD ~@W~ ~om the Beltway (I-495f take Exit 39 onto River lRoad (MD 190) inward toward DC and Bethesda approx. 1 mile. Tum left onto Beech Tree Road. ...A... Burning Tree Elementary 11111 School will be approx. 1/ 4 mile on the left . Northern Virginia ommunity College (NOVA) Table of Contents From the President Volume 16 April 1994 Number 4 TheTCS As It Evolves Club News Artist on Exhibit ........................ 26 by Lorin Evans by Blake Lange WAPHotline ........................ 39, 42 Macintosh Tutorials ................... 28 he operation of an electronic WAP Calendar ..................... 40, 41 Tutorial Registration Form ........ 29 bulletin board such as ours is a ln:dex to Advertisers .................... 2 Special Computer Offer ............. 30 T Classified Advertisements ......... 79 never-ending cycle of moderniza WAP Membership Form ............ 80 tion, expansion, and upgrade. The current TCS is a full replacement Apple II Articles for the Corvus network that was SIGs and Slices Teach a New Trick to a Venerable cajoled and coerced into the 20th Computer century. This first year of opera Stock SIG ..................................... 7 Dave & Joan Jernigan ........... 35 tion has given us a good idea as to by Morris Pelham Notes from the Apple II Vice what our members would like to see Mac Programmers' SIG .............. -

Power Macintosh 5500 and 6500 Computers

Developer Note Power Macintosh 5500 and 6500 Computers Developer Note © Apple Computer, Inc. 1997 Apple Computer, Inc. Corporation, used under license © 1997 Apple Computer, Inc. therefrom. All rights reserved. The word SRS is a registered trademark No part of this publication may be of SRS Labs, Inc. reproduced, stored in a retrieval Simultaneously published in the United system, or transmitted, in any form or States and Canada. by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of LIMITED WARRANTY ON MEDIA AND Apple Computer, Inc., except to make a REPLACEMENT backup copy of any documentation If you discover physical defects in the provided on CD-ROM. Printed in the manual or in the media on which a software United States of America. product is distributed, ADC will replace the The Apple logo is a trademark of media or manual at no charge to you Apple Computer, Inc. provided you return the item to be replaced Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo with proof of purchase to ADC. (Option-Shift-K) for commercial ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES ON THIS purposes without the prior written MANUAL, INCLUDING IMPLIED consent of Apple may constitute WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY trademark infringement and unfair AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR competition in violation of federal and PURPOSE, ARE LIMITED IN DURATION state laws. TO NINETY (90) DAYS FROM THE DATE No licenses, express or implied, are OF THE ORIGINAL RETAIL PURCHASE granted with respect to any of the OF THIS PRODUCT. technology described in this book. Even though Apple has reviewed this Apple retains all intellectual property manual, APPLE MAKES NO WARRANTY rights associated with the technology OR REPRESENTATION, EITHER EXPRESS described in this book. -

Apple Module Identification )

) Apple Module Identification ) PN: 072-8124 ) Copyright 1985-1994 by Apple Computer, Inc. June 1994 ( ( ( Module Identification Table of Contents ) Module Index by Page Number ii Cross Reference by Part Number xv CPU PCBs 1 .1 .1 Keyboards 2.1.1 Power Supplies 3.1.1 Interface Cards 4.1.1 Monitors 5.1.1 Drives 6.1.1 Data Communication 7.1.1 ) Printers 8.1.1 Input Devices 9.1.1 Miscellaneous 10.1.1 ) Module Identification Jun 94 Page i Module Index by Page Number Description Page No. CPU PCBs Macintosh Plus Logic Board 1 .1 .1 Macintosh Plus Logic Board 1.1.2 Macintosh II Logic Board 1.2.1 Macintosh II Logic Board 1.2.2 Macintosh IIx Logic Board 1.2.3 Macintosh Ilx Logic Board 1.2.4 Macintosh Ilcx Logic Board 1.2.5 Macintosh Ilcx Logic Board 1.2.6 Apple 256K SIMM, 120 ns 1.3.1 Apple 256K SIMM, DIP, 120 ns 1.3.2 Apple 256K SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.3 Apple 1 MB SIMM, 120 ns 1.3.4 Apple 1 MB SIMM, DIP, 120 ns 1.3.5 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.6 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.7 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns, Parity 1.3.S Apple 2 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.9 Apple 512K SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.10 Apple 256K SIMM, VRAM, 100 ns 1.3.11 Apple 256K SIMM, VRAM, SO ns 1.3.12 ( Apple 512K SIMM, VRAM 1.3.13 Macintosh/Macintosh Plus ROMs 1.3.14 Macintosh SE and SE/30 ROMs 1.3.15 Macintosh II ROMs 1.3.16 Apple 4 MB SIMM, 60 ns, 72-Pin 1.3.17 Apple S MB SIMM, 60 ns, 72-Pin 1.3.1S Apple 4 MB x 9 SIMM, SO ns, Parity 1.3.19 Apple 12SK SRAM SIMM, 17 ns 1.3.20 Apple 256K SRAM SIMM, 17 ns 1.3.21 Apple 4SK Tag SRAM SIMM, 14 ns 1.3.22 Macintosh SE Logic Board 1.4.1 Macintosh SE Revised Logic Board 1.4.2 Macintosh SE SOOK Logic Board 1.4.3 Macintosh SE Apple SuperDrive Logic Board 1.4.4 Macintosh SE/30 Logic Board 1.4.5 Macintosh SE/30 Logic Board 1.4.6 Macintosh SE Analog Board 1.4.7 Macintosh SE Video Board 1.4.S ( Macintosh Classic Logic Board 1.5.1 Macintosh Classic Power Sweep Board (110 V) Rev. -

IM: D: SCSI Manager

CHAPTER 4 SCSI Manager 4.3 4 SCSI Manager 4.3 is an enhanced version of the SCSI Manager that provides new features as well as compatibility with the original version. SCSI Manager 4.3 is contained in the ROM of high-performance computers such as the Macintosh Quadra 840AV and the Power Macintosh 8100/80. Beginning with system software version 7.5, SCSI Manager 4.3 is also available as a system extension that can be installed in any Macintosh computer that uses the NCR 53C96 SCSI controller chip. In addition to the capabilities of the original SCSI Manager, SCSI Manager 4.3 provides ■ support for asynchronous SCSI I/O ■ support for optional SCSI features such as disconnect/reconnect ■ a hardware-independent programming interface that minimizes the SCSI-specific tasks a device driver must perform You should read this chapter if you are writing a SCSI device driver or other software for Macintosh computers that use SCSI Manager 4.3. To make best use of this chapter, you should understand the Device Manager and the implementation of device drivers in Macintosh computers. If you are designing a SCSI peripheral device for the Macintosh, you should read Designing Cards and Drivers for the Macintosh Family, third edition, and Guide to the Macintosh Family Hardware, second edition. This chapter assumes you are familiar with the following SCSI specifications established by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI): 4 ■ X3.131-1986, Small Computer System Interface ■ X3.131-1994, Small Computer System Interface–2 SCSI Manager 4.3 ■ X3.232 (draft), SCSI-2 Common Access Method If you are writing a device driver for a block-structured storage device such as hard disk, you should also read the chapter “SCSI Manager” in this book for information about the structure of block devices used by the Macintosh Operating System. -

UMTRI-2000-20 Full Report (.Pdf)

- Technical Report UMTRI-2000-20 May, 2000 Navigation System Destination Entry: The Effects of Driver Workload and Input Devices, And Implications for SAE Recommended Practice. Christopher Nowakowski Yoshihiko Utsui Paul Green ,%\" OF 'Qjc frv * The University of Michigan a ,,,, UMTRl Transportation Research Institute Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. U MTRI-2000-20 4. Title and Subtltle b. Heport Date Navigation System Destination Entry: May, 2000 6. Pertormlng Organization Code The Effects of Driver Workload and Input Devices, account 377218 and Implications for SAE Recommended Practice 7. Author@) 8. Pertormlng Urganlzatlon Hepolt No. Christopher Nowakowski, Yoshihiko Utsui, U MTRI-2000-20 and Paul Green 9. Pertormina Uraanlzation Name and Address lo. Work Unit no. (TRAIS) The unheisity of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI) 2901 ~axterRd, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-2150 USA 72, sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type ot Report and Period Covered Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 9/99 - 512000 Industrial Electronics and Systems Laboratory 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 1-1, Tsukaguchi-Honmachi 8-Chome Amagaski City, Hyogo 661-8661 Japan 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract Sixteen licensed drivers, 8 younger (20 to 28 years old, mean of 25) and 8 older (55 to 65 years old, mean of 60), entered destinations by (1) entering addresses with the keyboard, (2) selecting them from a list using the keyboard, and (3) selecting them from a list using a remote control. The tasks were performed in a driving sirnullator both statically and under various driving workloads. The mean total task times for list selection and address entry, respectively, was 18 and 71 seconds for younger drivers and 32 and 145 seconds for older drivers. -

Macintosh Quadra 840AV System Fact Sheet SYSTEM POWER PORTS ADB: 1 Introduced: July 1993 Max

Macintosh Quadra 840AV System Fact Sheet SYSTEM POWER PORTS ADB: 1 Introduced: July 1993 Max. Watts: 200 Video: DB-15 Discontinued: July 1994 Amps: 9.00 Floppy: none Gestalt ID: 78 BTU Per Hour: 684 SCSI: DB-25 Form Factor: Quadra 800 Voltage Range: 100-240 GeoPort Connectors: 1 Weight (lbs.): 25.3 Freq'y Range (Hz): 50-60 Ethernet: AAUI-15 Dimensions (inches): 14 H x 7.7 W x 15.75 D Battery Type: 3.6V lithium Microphone Port Type: PlainTalk Soft Power Printer Speaker Codename: Quadra 1000, Cyclone Monitor Power Outlet Headphone Oder Number: Modem KB Article #: 12739 Airport Remote Control Includes S-video and RCA ports for video in and out. 1 VIDEO Built-in Display: none Maximum Color Bit-depth At: 512 640 640 640 800 832 1024 1152 1280 VRAM Speed: VRAM Needed: Video Configuration: x384 x400 x480 x8702 x600 x624 x768 x870 x1024 80 ns built in 1MB VRAM 24 24 16 8 16 16 8 8 n/a 4x256K 2MB VRAM 24 24 24 8 24 24 16 16 n/a 1 1-bit = Black & White; 2-bit = 4 colors; 4-bit = 16 colors; 8-bit = 256 colors; 16-bit = Thousands; 24-bit = Millions 2 The maximum color depth listed for 640x870 is 8-bit, reflecting the capabilities of the Apple 15" Portrait Display. LOGIC BOARD MEMORY Main Processor: 68040, 40 MHz Memory on Logic Board: none PMMU: integrated Minimum RAM: 4 MB FPU: integrated Maximum RAM: 128 MB Data Path: 32-bit, 40 MHz RAM Slots: 4 72-pin L1 Cache: 8K Minimum RAM Speed: 60 ns L2 Cache: none RAM Sizes: 4, 8, 16, 32 MB Secondary Processor: AT&T 3210 DSP, 66.67 MHz Install in Groups of: 1 Slots: 3 NuBus Speech Recognition Supported Supported -

Ports and Pinouts

K Service Source Ports and Pinouts Ports and Pinouts Cable Connectors - 1 Cable Connectors The pin numbers shown are for the connectors attached to the ends of the Macintosh peripheral cables, as viewed from the front of the connector. 152 Processor-Direct Slot, 152-Pin 77 76 HDI-30 1 HDI-20 PowerBook Video 25 14 2 30 20 16 6 1 5 1 13 1 HDI-45-pin Mini DIN-4 Apple Desktop Bus Apple AAUI 45 44 43 37 36 35 3 4 (Ethernet) 28 1 7 34 27 19 18 12 2 1 8 3 14 11 10 9 3 2 1 S-Video Mini Din-7Serial Mini Din-8 GeoPort Mini Din-9 7 7 7 4 3 6 8 8 6 IN 2 1 3 5 5 3 9 4 6 5 2 1 2 1 4 DB-15 Mini DIN-4 S-Video 1 8 3 4 2 1 9 15 DB-25 1 13 Composite Video (RCA jack) IN/OUT RF Input 14 25 Sig Gnd 1 25 BR-50 26 50 Microphone Jack Ports and Pinouts GeoPort Mini DIN-9 - 2 GeoPort Mini DIN-9 The back panel of all Power Macintosh models contain two I/O ports for serial telecommunication data. Both sockets accept 9-pin plugs, allowing either port to be independently programmed for asynchronous or synchronous communication formats up to 9600 bps. This includes AppleTalk and the full range of Apple GeoPort protocols. Pin Name Function 1 SCLK (out) Reset pod or get pod attention 2 Sync (in)/SCLK (in) Serial clock from pod (up to 920 Kbit/sec.) 3 TxD- Transmit - 4 Gnd/shield Ground 5 RxD- Receive - 6 TxD+ Transmit + 7 Wake up/TxHS Wake up CPU or do DMA handshake 8 RxD+ Receive + 9 +5V Power to pod (350 mA maximum) Ports and Pinouts Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) Connector - 3 Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) Connector Connector type: Mini DIN-4 male. -

GW4404A and GW4405A 68-Pin VRAM SIMM

Garrett’s Workshop GW4404A / GW4405A 256 kB / 512 kB 68-pin VRAM SIMM for Macintosh User’s Guide GW4404A and GW4405A were designed by Zane Kaminski and Garrett Fellers Overview GW4404A and GW4405A are 68-pin VRAM SIMMs which provide Apple Macintosh computers with 256 kB or 512 kB of VRAM, respectively. High-Quality PCB GW4404A and GW4405A are built with an ENIG gold-plated, 4-layer PCB, and only new parts are used to build the VRAM SIMMs. All units are tested extensively before shipment, and all SIMMs conform to 80 ns timing or better, ensuring compatibility with all Macintosh models which support 68-pin VRAM SIMMs. Excellent Signal Integrity GW4404A and GW4405A feature solid power and ground planes. Particular attention was paid to signal integrity, ensuring reliable performance on the fastest machines. The address bus traces are run as asymmetric striplines shielded inside the SIMM PCB, reducing interference generated by large VRAM SIMM arrays such as on the Quadra 700. Ample separation is provided between the DQ and SDQ buses routed on the front-side of the board. Particular attention was paid to the edge-sensitive RAS, CAS, and SCLK signals. These are optimized for minimum length, with large spacing between these edge-sensitive signals and all other signals and buses. Open-Source Design GW4404A and GW4405A’s designs are fully open-source. The schematics and board layouts are all freely available for commercial and noncommercial use. To download the design files, visit the Garrett's Workshop GitHub page: https://github.com/garrettsworkshop Physical Dimensions Parameter Value Height 20.32 mm ± 0.2 mm Width 102.87 mm ± 0.2 mm Thickness < 8 mm Weight < 28 g Compatibility All possible VRAM configurations are listed below by machine. -

Introduction Gestalt

Gestalt & _SysEnvirons - A Never-Ending Story Page: 1 CONTENTS This Technical Note discusses the latest changes and improvements to the _Gestalt Introduction and _SysEnvirons calls. _Gestalt [Sep 01 1994] Additional Gestalt Response Values gestaltHardwareAttr Selector SysEnvirons Calling _SysEnvirons From a High-Level Language Additional _SysEnvirons Constants References Change History Downloadables Introduction Previous versions of this Note provided the latest documentation on new information the _SysEnvirons trap could return. Developer Support Center (DSC) will continue to revise this Note to provide this information; however, as the _Gestalt trap is now the preferred method for determining information about a machine environment, this Note will also provide up-to-date information on _Gestalt selectors. Back to top _Gestalt This Note now documents _Gestalt selectors and return values added since the release of Inside Macintosh Volume VI. Please note that this is supplemental information; for the complete description of _Gestalt and its use, please refer to Inside Macintosh Volume VI. The Macintosh LC II is identical to the Macintosh LC except for the presence of an MC68030 processor, so under System 7.0.1 it returns the same gestaltMachineType response as the Macintosh LC (that is, 19). However, under System 7.1 and later, the LC II responds to a gestaltMachineType selector with the value 37. Thus, there are two cases when you are on an LC II: under System 7.0.1, you will get a gestaltMachineType response of gestaltMacLC (19), but gestaltProcessorType will return gestalt68030; under future system software, gestaltMachineType will return gestaltMacLCII (37). The processor will, of course, still be a 68030. -

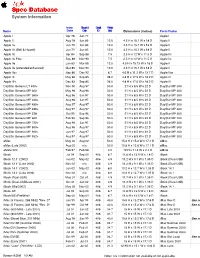

System Information

System Information Intro. Discont' d Gestalt Weight Name Date Date ID (lbs.) Dimensions (inches) Form Factor Apple I Apr 76 Jan 77 Apple I Apple II Aug 78 Jun 83 12.0 4.5 H x 15.1 W x 18 D Apple II Apple II+ Jun 79 Jun 83 12.0 4.5 H x 15.1 W x 18 D Apple II Apple II+ (Bell & Howell) Jun 79 Jun 83 12.0 4.5 H x 15.1 W x 18 D Apple II Apple IIc Apr 84 Sep 88 7.5 2.5 H x 12 W x 11.5 D Apple IIc Apple IIc Plus Sep 88 Nov 90 7.5 2.5 H x 12 W x 11.5 D Apple IIc Apple IIe Jan 83 Mar 85 12.0 4.5 H x 15.13 W x 18 D Apple II Apple IIe (extended/enhanced) Mar 85 Nov 93 12.0 4.5 H x 15.1 W x 18 D Apple II Apple IIgs Sep 86 Dec 92 8.7 4.6 H x 11.2 W x 13.7 D Apple IIgs Apple III May 80 Sep 85 26.0 4.8 H x 17.5 W x 18.2 D Apple III Apple III+ Dec 83 Sep 85 26.0 4.8 H x 17.5 W x 18.2 D Apple III DayStar Genesis LT 400+ Nov 96 Aug 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 300 May 96 Aug 96 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 360+ Aug 96 Jan 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 400+ Aug 96 Jan 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 450+ Aug 97 Aug 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 466+ Aug 97 Aug 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 528 Oct 95 Sep 96 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 600 Feb 96 Sep 96 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 720+ Aug 96 Jan 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar MP 300 DayStar Genesis MP 800+ Aug 96 Aug 97 50.0 21 H x 8.5 W x 22 D DayStar