Chapter Two R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cc 5 Pg Sem-Ii Train to Pakistan

CC 5 PG SEM-II TRAIN TO PAKISTAN- FILM AND LITERATURE Text Link: - http://punjabilibrary.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Train-To-Pakistan_Punjabi- Library.pdf? Film Link: - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3kUSLdKzU4 Train to Pakistan tells the story of imaginary Mano Majra, a small village town. Train to Pakistan film, an adaptation from Khushwant Singh's 1956 classic novel by the same name set in the Partition of India of 1947 and directed by Pamela Rooks was released in 1998. The film stars Nirmal Pandey, Rajit Kapur, Mohan Agashe, Smriti Mishra, Mangal Dhillon and Divya Dutta. Plot Analysis Train to Pakistan is a harrowing tale of a country divided by religious and political differences. The narrative takes place during the historic Partition of India in the summer of 1947, which is considered one of the bloodiest times in the country’s history. This division of India into two separate states caused a nationwide resettlement, thus dividing the previously single country into a Hindu India and a Muslim Pakistan, with devastating results. With the division of the country on the basis of belief systems, Singh’s narrative marks how entire families were made to abandon their lives and uproot themselves to re-align their lives based on religious allegiance to ensure safety and survival. The resettlement, however, was anything but safe and secure for those caught up in the ensuing violence. Trying to quickly avoid the oncoming troubles, people fled on foot, cart and train. Yet as these refugees attempted to flee the violence, they often became caught up in sanctioning violence themselves or were the victims of violence as Hindus and Muslims fought all over the country. -

Ssc Special Daily Quiz -740 Total Questions-40, Time - 40 Minutes, Marks - 40 Arena of General Knowledge 1

DAILY QUIZ-740 (11.09.2019) TEST YOURSELF SSC SPECIAL DAILY QUIZ -740 TOTAL QUESTIONS-40, TIME - 40 MINUTES, MARKS - 40 ARENA OF GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. Which of the following is in liquid form at room temperature? (a) Cerium (b) Sodium (c) Francium (d) Lithium 2. Soda water contains (a) Nitrous Acid (b) Carbonic Acid (c) Carbon Dioxide (d) Sulphur Acid 3. Which of the following is not an isotope of hydrogen? (a) Protium (b) Yttrium (c) Deuterium (d) Trituim 4. Polythene is industrially prepared by the polymerization of (a) Methane (b) Styrene (c) Acetylene (d) Ethylene 5. Which of the following is not a chemical reaction? (a) Burning of Paper (b) Digestion of Food (c) Conversion of Water into Steam (d) Burning of Coal 6. What is condensation? (a) Change of Gas into Solid (b) Change of Solid into Liquid (c) Change of Vapour into Liquid (d) Change of Heat Energy into Cooling Energy 7. During the development of an embryo the formation of brain marks the beginning of organ formation. Eye in a vertebrate develops from midbrain. If after the formation of brain the mid brain is destroyed then what will be the resultant effect? (a) Total Failure of Eye Formation (b) Development of a Single Eye (c) Defective Development of Eyes (d) Absence of Vision in the Eyes 8. The artificial rearing of honey bees is called (a) Sylviculture (b) Sericulture (c) Apiculture (d) Lociculture 9. Pineapple is a (a) Single Fruit (b) Collection of Fruit (c) Stem of the Plant (d) Collection of Leaves 10. The disease trachoma is related to the (a) Eye (b) Ear (c) Mouth (d) Throat 11. -

An Annual Peer-Reviewed Journal Vol

ISSN-L 0537-1988 57 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Peer-reviewed Journal Vol. LVII 2020 Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) The responsibility for facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any in this journal, is entirely that of the author(s). The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA www.aes-india.org 57 2020 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) www.aes-india.org The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES) published since 1940 accepts scholarly papers presented by the AESI members at the annual conferences of Association for English Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the copies of journal for home, college, university/departmental library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, by sending an e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are requested to place orders on behalf of their institutions for one or more copies. Orders by post can be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Indian Journal of English Studies, Anand Math, Near St. Paul School, Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 (Bihar) India. ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA Price: ``` 350 (for individuals) ``` 600 (for institutions) £ 10 (for overseas) Submission Guidelines Papers presented at AESI (Association for English Studies of India) annual conference are given due consideration, the journal also welcomes outstanding articles/research papers from faculty members, scholars and writers. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

Afrindian Fictions

Afrindian Fictions Diaspora, Race, and National Desire in South Africa Pallavi Rastogi T H E O H I O S TAT E U N I V E R S I T Y P R E ss C O L U MB us Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rastogi, Pallavi. Afrindian fictions : diaspora, race, and national desire in South Africa / Pallavi Rastogi. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-0319-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-0319-1 (alk. paper) 1. South African fiction (English)—21st century—History and criticism. 2. South African fiction (English)—20th century—History and criticism. 3. South African fic- tion (English)—East Indian authors—History and criticism. 4. East Indians—Foreign countries—Intellectual life. 5. East Indian diaspora in literature. 6. Identity (Psychol- ogy) in literature. 7. Group identity in literature. I. Title. PR9358.2.I54R37 2008 823'.91409352991411—dc22 2008006183 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–08142–0319–4) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–08142–9099–6) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Typeset in Adobe Fairfield by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri- can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction Are Indians Africans Too, or: When Does a Subcontinental Become a Citizen? 1 Chapter 1 Indians in Short: Collectivity -

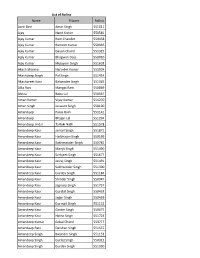

Name Fname Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor

List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Aarti Devi Amar Singh 551011 Ajay Nand Kishor 550581 Ajay Kumar Ram Chander 550458 Ajay Kumar Ramesh Kumar 550336 Ajay Kumar Gayan Chand 551315 Ajay Kumar Bhagwan Dass 550010 Ajay Kumar Mulayam Singh 551603 Akash Sharma Narinder Kumar 551904 Akashdeep Singh Pal Singh 551414 Akashpreet Kaur Balwinder Singh 551365 Alka Rani Mangat Ram 550869 Alvina Babu Lal 550561 Aman Kumar Vijay Kumar 551270 Aman Singh Jaswant Singh 550190 Amandeep Paras Ram 551141 Amandeep Bhajan Lal 551294 Amandeep Jindal Tarloki Nath 551578 Amandeep Kaur Jarnail Singh 551871 Amandeep Kaur Harbhajan Singh 550169 Amandeep Kaur Sukhmander Singh 550781 Amandeep Kaur Manjit Singh 551490 Amandeep Kaur Sarbjeet Singh 551677 Amandeep Kaur Jasraj Singh 551491 Amandeep Kaur Sukhwinder Singh 551300 Amandeep Kaur Gurdev Singh 551184 Amandeep Kaur Shinder Singh 550347 Amandeep Kaur Jagroop Singh 551737 Amandeep Kaur Gurdial Singh 550453 Amandeep Kaur Jagsir Singh 550459 Amandeep Kaur Gurmail SIngh 551122 Amandeep Kaur Ginder Singh 550675 Amandeep Kaur Natha Singh 551724 Amandeep Kumar Gokal Chand 550777 Amandeep Rani Darshan Singh 551537 Amandeep Singh Baljinder Singh 551153 Amandeep Singh Gurtej Singh 550312 Amandeep Singh Gurdev Singh 551030 List of Rollno Name FName Rollno Amandeep Singh Balwinder SIngh 550016 Amandeep Singh Surjeet Singh 551251 Amandeep Singh Subhash Singh 551637 Amandeep Singh Angraj Singh 551622 Amandeep Singh Gurcharan Singh 551596 Amandeep Singh Nathu Ram 550748 Amandeep Singh Jarnail Singh 550058 Amandeep Singh Shinder -

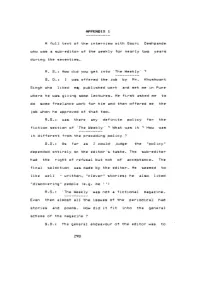

APPENDIX 1 a Full Text of the Interview with Gauri Deshpande Who Was A

APPENDIX 1 A full text of the interview with Gauri Deshpande who was a sub-editor of the weekly for nearly two years during the seventies. R. S.: How did you get into The Weekly' ? G. D.: I was offered the job by Mr. Khushwant Singh who liked m«y published work and met me in Pune where he was giving some lectures. He first asked me to do some freelance work for him and then offered me the job when he approved of that too. R.S.: was there any definite policy for the fiction section of "The Weekly' ? What was it ? How was it different from the preceding policy ? B.D.: As far as I could judge the "policy" depended entirely on the editor's taste. The sub-editor had the right of refusal but not of acceptance. The final selection was made by the editor. He seemed to like well - written, "clever" stories; he also liked "discovering" people (e.g. me II) R.S.: 'The Weekly' was not a fictional magazine. Even then almost all the issues of the periodical had stories and poems. How did it fit into the general scheme of the magazine ? G.D.: The general endeavour of the editor was to 298 make 'The Weekly' into a brighter, more popular, more accessible paper; less 'colonial' if one can say that. The changes he made in typography, layout, covers, photographs, even payment scales, all point to this. The often controversial themes of his main photo features (e.g. communities of india) and the bright new look fiction were part of the general policy. -

The Partition of India Midnight's Children

THE PARTITION OF INDIA MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN, MIDNIGHT’S FURIES India was the first nation to undertake decolonization in Asia and Africa following World War Two An estimated 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of India Partition saw the largest migration of humans in the 20th Century, outside war and famine Approximately 83,000 women were kidnapped on both sides of the newly-created border The death toll remains disputed, 1 – 2 million Less than 12 men decided the future of 400 million people 1 Wednesday October 3rd 2018 Christopher Tidyman – Loreto Kirribilli, Sydney HISTORY EXTENSION AND MODERN HISTORY History Extension key questions Who are the historians? What is the purpose of history? How has history been constructed, recorded and presented over time? Why have approaches to history changed over time? Year 11 Shaping of the Modern World: The End of Empire A study of the causes, nature and outcomes of decolonisation in ONE country Year 12 National Studies India 1942 - 1984 2 HISTORY EXTENSION PA R T I T I O N OF INDIA SYLLABUS DOT POINTS: CONTENT FOCUS: S T U D E N T S INVESTIGATE C H A N G I N G INTERPRETATIONS OF THE PARTITION OF INDIA Students examine the historians and approaches to history which have contributed to historical debate in the areas of: - the causes of the Partition - the role of individuals - the effects and consequences of the Partition of India Aims for this presentation: - Introduce teachers to a new History topic - Outline important shifts in Partition historiography - Provide an opportunity to discuss resources and materials - Have teachers consider the possibilities for teaching these topics 3 SHIFTING HISTORIOGRAPHY WHO ARE THE HISTORIANS? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF HISTORY? F I E R C E CONTROVERSY HAS RAGED OVER THE CAUSES OF PARTITION. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

The Inventory of the R.K. Narayan Collection #737

The Inventory of the R.K. Narayan Collection #737 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center \ ' I NARAYAN, R.K. Purchase August 1978 I. MANUSCRIPTS A. Novels Box l 1. THE PAINTER OF SIGNS. Viking, 1976. a. Miscellaneous draft pages. Holograph and typescript with holo. corr., ca. 200 p. on ca. 150 leaves. (#1) b. Photocopy of typescript with holo. corr., 261 p. (#2) c. Miscellaneous draft pages. Typescript photocopy with holo. corr. and typescript with holo. corr., 19 p. (#3) 2. VENDOR OF SWEETS. Viking, 1967. Carbon typescript with holo. corr., 236 p. ( #4) B. Plays 1. THE HOME OF THUNDER. Typescript, 64 p. (#5) 2. ON EVEREST. Carbon typescript, 11 p. With TLS from his agents, David Higham Associates, July 24, 1969. (#6) 3. WATCHMAN OF THE LAKE. (#7) a. Typescript with holo. corr., 10 p. (incomplete) b. Typescript with holo. corr., 20 p. c. Short Stories Box 2 1. A HORSE AND TWO GOATS. Short story collection. Viking. a. Typescript and carbon typescript, with holo. corr. and tearsheets, ca. 160 p. incl. front matter, ink and wash illustrations with proofs; layout for title page and first story. (#1) b. Page proofs. (#2) 11 11 c. Re story: A Breath of 'Lucifer • TLS from Wi 11 iam Morris Agency, Dec. 26, 1968; Memo from Viking Press, Jan. 17, 1969. (#2) NARAYAN, R.K. / Page 2. Box 2 2. "Uncle" (#3) a. Typescript with holo. corr., 63 p. in folder, marked "Discarded earlier version" b. Holograph notes, 2 p. D. Autobiography MY DAYS. Viking, 1973. l. Holograph, 32 p. on 18 leaves.