The Sleep of Elijah by Philippe De Champaigne from the Convent of the Val-De-Grâce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

A Private Mystery: Looking at Philippe De Champaigne’S Annunciation for the Hôtel De Chavigny

chapter 20 A Private Mystery: Looking at Philippe de Champaigne’s Annunciation for the Hôtel de Chavigny Mette Birkedal Bruun Mysteries elude immediate access. The core meaning of the Greek word μυστήριον (mystérion) is something that is hidden, and hence accessible only through some form of initiation or revelation.1 The key Christian mysteries concern the meeting between Heaven and Earth in the Incarnation and the soteriological grace wielded in Christ’s Passion and Resurrection as well as in the sacraments of the Church. Visual representations of the Christian myster- ies strive to capture and convey what is hidden and to express the ineffable in a congruent way. Such representations are produced in historical contexts, and in their aspiration to represent motifs that transcend time and space and indeed embrace time and space, they are marked through and through by their own Sitz-im-Leben. Also, the viewers’ perceptions of such representations are embedded in a historical context. It is the key assumption of this chapter that early modern visual representations of mysteries are seen by human beings whose gaze and understanding are shaped by historical factors.2 We shall approach one such historical gaze. It belongs to a figure who navigated a particular space; who was born into a particular age and class; endowed with a particular set of experiences and aspirations; and informed by a particular devotional horizon. The figure whose gaze we shall approach is Léon Bouthillier, Comte de Chavigny (1608–1652). The mystery in focus is the Annunciation, and the visual representation is the Annunciation painted 1 See Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance, “3466. -

Symbolism and Politics: the Construction of the Louvre, 1660-1667

Symbolism and Politics: The Construction of the Louvre, 1660-1667 by Jeanne Morgan Zarucchi The word palace has come to mean a royal residence, or an edifice of grandeur; in its origins, however, it derives from the Latin palatium, the Palatine Hill upon which Augustus established his imperial residence and erected a temple to Apollo. It is therefore fitting that in the mid-seventeenth century, the young French king hailed as the "new Augustus" should erect new symbols of deific power, undertaking construction on an unprecedented scale to celebrate the Apollonian divinity of his own reign. As the symbols of Apollo are the lyre and the bow, so too were these constructions symbolic of how artistic accomplishment could serve to manifest political power. The project to enlarge the east facade of the Louvre in the early 1660s is a well-known illustration of this form of artistic propaganda, driven by what Orest Ranum has termed "Colbert's unitary conception of politics and culture (Ranum 265)." The Louvre was also to become, however, a political symbol on several other levels, reflecting power struggles among individual artists, the rivalry between France and Italy for artistic dominance, and above all, the intent to secure the king's base of power in the early days of his personal reign. In a plan previously conceived by Cardinal Mazarin as the «grand dessin,» the Louvre was to have been enlarged, embellished, and ultimately joined to the Palais des Tuileries. The demolition of houses standing in the way began in 1657, and in 1660 Mazarin approved a new design submitted by Louis Le Vau. -

The Good Shepherd

The Good Shepherd ART PRINT 22 GRADE 1, UNIT 5, SESSION 22 CATECHIST DIRECTIONS MATERIALS ▶▶ The Good Shepherd Catechist Guide page 131 Art Print 1 Begin Faith Focus: Jesus cares for us like a shepherd cares ▶▶ Children’s Book page 234 for his sheep. After completing page 131 in the Children’s Book, display the Art Print. TIME OUTCOMES Briefly introduce and discuss the artwork, using 10–30 minutes ▶▶ Tell the story of the lost sheep. information from About the Artist and Artifacts. ▶▶ Describe how Jesus is the Good Shepherd. Ask: Whom do you see in this painting? (Jesus) Tel l ▶▶ Explain that God’s love is greater than any sin. children that this artwork shows Jesus as a shepherd. Ask: What does a shepherd do? (takes care of sheep) Say: Where Jesus grew up, being a shepherd was a very common job. Shepherds took good care of their flocks of sheep, protecting them from danger, feeding them, giving them shelter, About the Artist Philippe de Art•i•facts The Good Shepherd is an and keeping them together so that none got lost. Like a shepherd, Jesus Champaigne (1602–1674) was born in example of Baroque art. Baroque art is a takes good care of us. He protects us from harm, feeds us through the Brussels, Belgium. He first studied art with term that describes an artistic style that Eucharist, and keeps us together as God’s family. landscape painter Jacques Fouquières. originated in Rome at the beginning of Invite children to reflect on the artwork and to pray a silent prayer asking In 1621 he moved to Paris, where he the 17th century. -

Press Kit Louvre Power Plays

PRESS KIT Power Plays Exhibition September 27, 2017 - July 2, 2018 Petite Galerie du Louvre Press Contact Marion Benaiteau [email protected] Tél. + 33 (0)1 40 20 67 10 / + 33 (0)6 88 42 52 62 1 SOMMAIRE Press Release page 3 The Exhibition Layout page 5 Press Visuals page 7 2 Press release Art and Cultural Education September 27, 2017 – July 2, 2018 Petite Galerie du Louvre Power Plays The Petite Galerie exhibition for 2017–2018 focuses on the connection between art and political power. Governing entails self- presentation as a way of affirming authority, legitimacy and prestige. Thus art in the hands of patrons becomes a propaganda tool; but it can also be a vehicle for protest and subverting the established order. Spanning the period from antiquity up to our own time, forty works from the Musée du Louvre, the Musée National du Château de Pau, the Château de Versailles and the Musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris illustrate the evolution of the codes behind the representation of political power. The exhibition is divided into four sections: "Princely Roles": The first room presents the king's functions— priest, builder, warrior/protector—as portrayed through different artistic media. Notable examples are Philippe de Champaigne's Louis XIII, Léonard Limosin's enamel Crucifixion Altarpiece, and the Triad of Osorkon II from ancient Egypt. "Legitimacy through Persuasion": The focus in the second Antoine-François Callet, Louis XVI, 1779, oil on canvas, room is on the emblematic figure of Henri IV, initially a king Musée du Château de Versailles © RMN-Grand Palais in search of legitimacy, then a model for the Bourbon heirs (Château de Versailles) / Christophe Fouin from Louis XVI to the Restoration. -

G Alerie Terrades

GALERIE TERRADES - PARIS 1600 - 1900 PAINTINGS | DRAWINGS 2020 GALERIE TERRADES - PARIS 1600 - 1900 PAINTINGS | DRAWINGS 2020 1600 PAINTINGS 1900 DRAWINGS Acknowledgments We are grateful to all those who have helped us, provided opinions and expertise in the preparation of this catalogue: Stéphane-Jacques Addade, Pr. Stephen Bann, Piero Boccardo, Guillaume Bouchayer, Vincent Delieuvin, Marie-Anne Destrebecq-Martin, Corentin Dury, Francesco Frangi, Véronique Gérard Powell, Ariane Yann Farinaux-Le Sidaner, James Sarazin, Frédérique Lanoë, Cyrille Martin (†), Christian Maury, Gianni Papi, Francesco Petrucci, Giuseppe Porzio, Jane Roberts, Guy Saigne, Schlomit Steinberg and Gabriel Weisberg Translation into English: Jane Mac Avock Cover: Léon Pallière, Rome, St. Peter’s Square from Bernini’s colonnade, n°8 (detail) Frontispice: Augustin-Louis Belle, Herse, Daughter of Cecrops, sees Mercury Going Towards her Palace, n°9 (detail) Objects are listed in chronological order of creation Dimensions are given in centimetres, height precedes width for the paintings and drawings CATALOGUE Simone Barabino Val Pocevera, c. 1584/1585– Milan, 1629 1. Lamentation of Christ, c. 1610 Oil on canvas Barabino, who was born in Val Polcevera near the early works of Bernardo Strozzi. The wide range 43.5 x 29 cm Genoa, was apprenticed to Bernardo Castello, one of colours, complemented by iridescent shades owes of the city’s principal Mannerist painters. But much to the study of the Crucifixion, the masterpiece the master’s excessive jealously caused a violent by Barocci in the cathedral of Genoa, while Christ’s break in their relations in 1605. Barabino then set pale body is probably connected to the observation up as an independent painter, quickly becoming of Lombard paintings by Cerano, Procaccini and successful with religious congregations (The Last Morazzone that could be seen in Genoa. -

Louis Marin's Plea for Poussin As a Painter

This is a repository copy of Legacies of ‘Sublime Poussin’: Louis Marin’s plea for Poussin as a painter. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/96935/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Saint, NW (2016) Legacies of ‘Sublime Poussin’: Louis Marin’s plea for Poussin as a painter. Early Modern French Studies, 38 (1). pp. 59-73. ISSN 2056-3035 https://doi.org/10.1080/20563035.2016.1181427 (c) 2016, Taylor & Francis. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Early Modern French Studies on July 2016,, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20563035.2016.1181427 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Legacies of Sublime Poussin: Louis M P P P Nigel Saint (University of Leeds) L grande théorie et pratique (Poussin, Letter to Chantelou, 24 November 1647)1 Introduction L M American sojourns in the 1970s, followed by further visits in the 1980s, have arguably obscured his period of residence in London in the 1960s. -

John Walker, Director of the National Gallery Of

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON 25 DC • REpublic 7-4215 extension 247 For Release: Sunday papers November 6, 1960 WASHINGTON, D 0 C 0 November 5, 1960: John Walker, Director of the National Gallery of Art, announced today that the most important exhibition of French seventeenth century art ever presented in the United States will open to the public at the Gallery on Thursday, November 10,, The exhibition, entitled THE SPLENDID CENTURY, will be on view in Washington through December 15. 166 masterpieces - paintings, drawings, sculpture and tapes tries - the majority of which have never been shown in the United States, have been lent by more than 40 of the provincial museums of France, as well as 4 churches, the Musee du Louvre and the Chateau of Versailles,, The exhibition of THE SPLENDID CENTURY has been organized to illustrate the variety of painting in this great artistic period, which extended from the death of Henry IV in 1610 to the years just after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. It will also show the underlying unity of balance and restraint which appeal to modern taste It is only in the last 30 years s for instance, that the works of Georges de la Tour have suddenly received world acclaim after having been practically forgotten for several centuries, Five paintings by La Tour will be on view, including the famous canvas of The Young Jesus_and St, Joseph in the Carpenter's Shop. (more) - 2 - Six canvases of Nicolas Poussin are included in the exhibition. He is generally conceded to be France's greatest classical painter and the artist whose genius dominates the century. -

Ground Layers in European Painting 1550–1750

Ground Layers in European Painting 1550–1750 CATS Proceedings, V, 2019 Edited by Anne Haack Christensen, Angela Jager and Joyce H. Townsend GROUND LAYERS IN EUROPEAN PAINTING 1550–1750 GROUND LAYERS IN EUROPEAN PAINTING 1550–1750 CATS Proceedings, V, 2019 Edited by Anne Haack Christensen, Angela Jager and Joyce H. Townsend Archetype Publications www.archetype.co.uk in association with First published 2020 by Archetype Publications Ltd in association with CATS, Copenhagen Archetype Publications Ltd c/o International Academic Projects 1 Birdcage Walk London SW1H 9JJ www.archetype.co.uk © 2020 CATS, Copenhagen The Centre for Art Technological Studies and Conservation (CATS) was made possible by a substantial donation by the Villum Foundation and the Velux Foundation, and is a collabora- tive research venture between the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), the National Museum of Denmark (NMD) and the School of Conservation (SoC) at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation. ISBN: 978-1-909492-79-0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher would be pleased to rectify any omissions in future reprints. Front cover illustration: Luca Giordano, The Flight into Egypt, c.1700, oil on canvas, 61.5 × 48.9 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, inv. -

Huntington Acquires Newly Identified Portrait by Major French Artist of the 17Th Century

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 12, 2010 CONTACTS: Thea M. Page, 6264052260, [email protected] Lisa Blackburn, 6264052140, [email protected] HUNTINGTON ACQUIRES NEWLY IDENTIFIED PORTRAIT BY MAJOR FRENCH ARTIST OF THE 17TH CENTURY Portrait of Jean de Thévenot by Philippe de Champaigne Goes on View Today Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674), Portrait of Jean de Thévenot (1633–1667), 1660–63. Oil on canvas; 23 ½ x 17 inches. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. SAN MARINO, Calif.—The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens has added to its holdings a newly identified painting by prominent 17thcentury French painter Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674). Selected for acquisition by The Huntington’s Art Collectors’ Council at its spring meeting, Portrait of Jean de Thévenot (1633–1667), painted between 1660 and 1663, had been misattributed to Dutch artist Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621–1674), but with the discovery in 1990 of a related painting in a private collection, it was established as a remarkable addition to Champaigne’s body of work. This year, with a comparison to an engraved portrait in a journal written by Orientalist and traveler Thévenot, the identity of the sitter was 2 Portrait of Jean de Thévenot determined. The sitter was previously identified as French linguist and archeologist Antoine Galland (1646 –1715), to whom the picture, however, bears little resemblance. Portrait of Jean de Thévenot goes on view today in the Huntington Art Gallery, providing an art historical bridge between works of 16th and 18thcentury European art. It will be a centerpiece in the new gallery of 17thcentury art to be reinstalled sometime next year. -

Portrait of Anne of Austria, 17Th Century

anticSwiss 27/09/2021 14:04:14 http://www.anticswiss.com Portrait of Anne of Austria, 17th century SOLD ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 17° secolo -1600 Villa Stampanoni Antiques Style: Gaiba Rinascimento, Luigi XIII Height:72cm 393386233246 Width:64cm Material:olio su tela Price:0000€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: Portrait of Anne of Austria (1601-1666) infant of Spain, archduchess of Austria, princess of Burgundy and princess of the Netherlands, queen of France and Navarre, wife of Louis XIII, daughter of King Philip III, king of Spain. Oil on canvas, France around 1635 Atelier of Philippe de Champaigne (1602 - 1674) Frame in carved, waxed and gilded Dutch oak, with stylized acanthus leaf decorations. Measures 72 cm X 64 cm Restored with only superficial cleaning. Dressed in immeasurable beauty, with silky curls that fall into a mother-of-pearl-colored décolleté, a dress of soft silk accentuated by an embroidered jewel that seems not to end and emerge from the canvas, her big eyes look at us, her lips tinted with strawberry color. entice you to look back. Portrayed half-length with all her charm, a beauty of yesteryear but completely current, she appreciates her simplicity of posture, accomplice of the skilful chiaroscuro that brush strokes have brought out. Words are inexpensive to describe the emotion, the vibration of a detail, the purity, the elegance of our queen of France and Navarre. Philippe de Champaigne (1602 - 1674) Born in Brussels, he settled permanently in Paris in 1621. A pupil of the painters Jean Bouillon and Michel de Bordeaux (from 1621), he trained together with Jacques Fouquières and Nicolas Poussin, to whom he always remained close from deep friendship. -

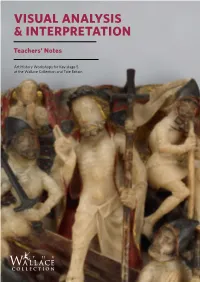

Visual Analysis & Interpretation

VISUAL ANALYSIS & INTERPRETATION Teachers’ Notes Art History Workshops for Key stage 5 at the Wallace Collection and Tate Britain 1 Visual Analysis & Interpretation Teachers’ Notes Art History Workshops for Key stage 5 at the Wallace Collection and Tate Britain These notes are designed to accompany KS5 The Workshops Workshops on Visual Analysis and Interpretation: Introducing Approaches to Art History. This workshop In both the 2 hours and the 4 hour workshop, the aims to provide an introduction to Art History early in day will begin with a brief introduction to the history Year 12, or to help students consolidate their learning of the Wallace Collection, the family and how later in the year or during Year 13. the collection was acquired. Whilst in the 2 hour workshop we focus on the Wallace Collection, in the Encouraging students to engage with a wide variety 4 hour workshop, we will also consider how or why of paintings and sculptures and through discussion the contents and nature of the collection might differ around each work of art, the students will develop from that of Tate Britain. their analytical and interpretive skills. The workshop aims to enable students to identify the formal and stylistic elements of paintings and sculpture from 4 hour workshop different historical periods. It will enable them to explore the materials and processes used in the After a morning session at the Wallace Collection, production of art and to gain an understanding of the the afternoon is spent at Tate Britain focusing varying contexts in which art works are made and upon the modern part of the collection, making seen.