Apocalyptic Thought in John Henry Newman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Henry Newman and the Significance of Theistic Proof

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 1983 John Henry Newman and the Significance of Theistic Proof Mary Susan Glasson University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Glasson, Mary Susan, "John Henry Newman and the Significance of Theistic Proof" (1983). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 1530. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - JOHNHENRY NEWMAN ANDTHE SIGNIFICANCE OF THEISTICPROOF BY MARYSUSAN GLASSON A THESISSUBMITTED IN PARTIALFULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTSFOR THE DEGREEOF MASTEROF ARTS IN PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITYOF RHODEISLAND 1983 ABSTRACT The central problem of this paper is to decide the significance of formal argument for God's existence, in light of John Henry Newman's distinction between notional and real assent. If God in fact exists, then only real assent to the proposition asserting his existence is adequate. Notional assent is inadequate because it is assent to a notion or abstraction, and not to a present reality. But on Newman's view it is notional assent which normally follows on a formal inference, therefore the significance of traditional formal arguments is thrown into question. Newman has claimed that our attitude toward a proposition may be one of three; we may doubt it, infer it, or assent to it, and to assent to it is to hold it unconditionally. -

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

The Wesleyan Enlightenment

The Wesleyan Enlightenment: Closing the gap between heart religion and reason in Eighteenth Century England by Timothy Wayne Holgerson B.M.E., Oral Roberts University, 1984 M.M.E., Wichita State University, 1986 M.A., Asbury Theological Seminary, 1999 M.A., Kansas State University, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Abstract John Wesley (1703-1791) was an Anglican priest who became the leader of Wesleyan Methodism, a renewal movement within the Church of England that began in the late 1730s. Although Wesley was not isolated from his enlightened age, historians of the Enlightenment and theologians of John Wesley have only recently begun to consider Wesley in the historical context of the Enlightenment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between a man, John Wesley, and an intellectual movement, the Enlightenment. As a comparative history, this study will analyze the juxtaposition of two historiographies, Wesley studies and Enlightenment studies. Surprisingly, Wesley scholars did not study John Wesley as an important theologian until the mid-1960s. Moreover, because social historians in the 1970s began to explore the unique ways people experienced the Enlightenment in different local, regional and national contexts, the plausibility of an English Enlightenment emerged for the first time in the early 1980s. As a result, in the late 1980s, scholars began to integrate the study of John Wesley and the Enlightenment. In other words, historians and theologians began to consider Wesley as a serious thinker in the context of an English Enlightenment that was not hostile to Christianity. -

The Importance of the Catholic School Ethos Or Four Men in a Bateau

THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS OR FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ruth Joy August 2018 A dissertation written by Ruth Joy B.S., Kent State University, 1969 M.S., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Natasha Levinson _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Averil McClelland _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Catherine E. Hackney Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Foundations, Leadership and Kimberly S. Schimmel Administration ........................ _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human Services James C. Hannon ii JOY, RUTH, Ph.D., August 2018 Cultural Foundations ........................ of Education THE AMERICAN COVENANT, CATHOLIC ANTHROPOLOGY AND EDUCATING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE CATHOLIC SCHOOL ETHOS. OR, FOUR MEN IN A BATEAU (213 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Natasha Levinson, Ph. D. Dozens of academic studies over the course of the past four or five decades have shown empirically that Catholic schools, according to a wide array of standards and measures, are the best schools at producing good American citizens. This dissertation proposes that this is so is partly because the schools are infused with the Catholic ethos (also called the Catholic Imagination or the Analogical Imagination) and its approach to the world in general. A large part of this ethos is based upon Catholic Anthropology, the Church’s teaching about the nature of the human person and his or her relationship to other people, to Society, to the State, and to God. -

Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2021): 60–89 Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse Kenneth Parker The whole Church, laity and hierarchy together, bears responsi- bility for and mediates in history the revelation which is contained in the holy Scriptures and in the living apostolic Tradition … [A]ll believers [play a vital role] in the articulation and development of the faith …. “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” 3.1, 67 International Theological Commission of the Catholic Church Rome, July 2014 N 2014, THE INTERNATIONAL THEOLOGICAL Commission pub- lished “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” which highlighted two critically important theological concepts: development and I sensus fidelium. Drawing inspiration directly from the works of John Henry Newman, this document not only affirmed the insights found in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which church authorities embraced during the first decade of New- man’s life as a Catholic, but also his provocative Rambler article, “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine” (1859), which resulted in episcopal accusations of heresy and Newman’s delation to Rome. The tension between Newman’s theory of development and his appeal for the hierarchy to consider the experience of the “faithful” ultimately centers on the “seat” of authority, and whose voices matter. As a his- torical theologian, I recognize in the 175 year reception of Newman’s theory of development, the controversial character of this historio- graphical assumption—or “metanarrative”—which privileges the hi- erarchy’s authority to teach, but paradoxically acknowledges the ca- pacity of the “faithful” to receive—and at times reject—propositions presented to them as authoritative truth claims.1 1 Maurice Blondel, in his History and Dogma (1904), emphasized that historians always act on metaphysical assumptions when applying facts to the historical St. -

Catholic University As Witness” with Guest, Patrick Reilly

The “Crisis of Truth” (and the Renewal) in American Catholic Education By Patrick J. Reilly, Papal Visit 2015 Commemorative Issue Patrick J. Reilly is president of The Cardinal Newman Jesuits. Their embrace of secular values and disdain for Society, which promotes and defends faithful Catholic Catholic orthodoxy have contributed substantially to education. the corruption of American society, including Catholic laity. The last time a Pontiff visited America, he urged Cath- olic school and college educators to confront the “con- And our treasured parochial school system is in decline. temporary crisis of truth” that is “rooted in a crisis of In the last 50 years, the number of Catholics in the faith.” United States in- creased nearly two- Speaking at The Catho- thirds to 80 million, but lic University of Amer- the number of students ica in Washington, in Catholic schools de- D.C., Pope Benedict in- clined by more than 60 vited a renewal of fidel- percent. Enrollment in ity, rededication to truth urban areas has de- and recommitment to clined by nearly a third the moral and religious in just the last decade. formation of students — and he rejected In San Francisco, Pope Americans’ radical ver- Francis can find evi- sion of “academic free- dence of another sort dom” which disregards of decline. More than truth and the common Students from Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia, carry the March 80 percent of the Arch- good. for Life banner in front of the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington January 22, diocese’s high school 2009. It was the 36th annual March for Life. -

Gilpin Family Rich.Ard De Gylpyn Joseph Gilpin The

THE GILPIN FAMILY FROM RICH.ARD DE GYLPYN IN 1206 IN A LINE TO JOSEPH GILPIN THE EMIGRANT TO AMERICA AND SOMETHING OF THE KENTUCKY GILPINS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS To 1916 Copyrighted in 1927 by Geor(Je Gilpin Perkins PRESS OF W, F- ROBERTS COMPANY WASHJNGTON, D, C. THE KENTUCKY GILPINS By GEORGE GILPIN PERKINS HIS genealogical study of the Gilpin families, covering the period of twenty generations prior to the Gil pin emigration to Kentucky, is gathered solely, so far as the simple line of descent goes, from an elaborate parchment pedi gree chart taken from the papers of Joshua Gilpin, Esquire, by his brother, Thomas Gilpin, Philadelphia, March, 1845, and in part, textu ally, from the work: by Dr. Joseph Elliott Gilpin, Baltimore, 1897, whose father and the Kentucky emigrants were brothers. His authority was a Genealogical Chart accompanying a manuscript published 1879 by the Cumberland and West moreland Antiquarian and Archreological Society of England entitled "Memoirs of Dr. Richard Gilpin of Scaleby Castle in Cumberland, written in the year 1791 by the Rev. William Gilpin, Vicar of Boldre, together with an account of the author by himself; and a pedigree of the Gilpin family." [ 5 ] T H E KENTUCKY GILPINS Richard de Gylpyn, the first of the name of whom there is authentic knowledge, was a scholar. He gave the family history a vigorous beginning, by becoming the Secretary and Adviser of the Baron of Kendal, who was unlearned, as were many in that day of superstition and igno rance, and accompanying him to Runnemede, where the Barons of England, after previous long parleys with the unscrupulous and tyrannical King John, forced him to grant to his oppressed people Magna Charta and, themselves, voluntarily lifted from their dependants many feudal op pressions. -

Parish Pump Parish

The Baptism of Christ Liturgical Colour: White 12th January 2014 A warm welcome to all. A special welcome to any visitors to the Benefice or those worshipping here for the first time. Woolavington Village Hall Saturday 25 January 2014, 7.30 pm TEAMS of 4, Entry £3.00 per person Light refreshments available PLEASE NOTE THERE WILL BE NO BAR THIS YEAR but please BYO ALCOHOLIC DRINKS (and glasses) Proceeds in aid of St. Mary’s Church Come and enjoy a traditional BURNS NIGHT Cossington Village Hall January 31st 2014—7.00pm prompt Entrance (inc 3-course meal) £12.50 Proceeds for St. Mary’s Church funds Parish Pump THE FOLLOWING COMMUNION PRAYER ROTA APPLIES 1st Sunday Woolavington (8 am) & Bawdrip: Prayer A 2nd Sunday Woolavington & Cossington Prayer H 3rd Sunday Woolavington, Family Communion Booklet, Bawdrip Prayer B 4th Sunday Woolavington & Cossington Prayer D UNITED BENEFICEOF WOOLAVINGTONWITH COSSINGTON AND BAWDRIP 5th Sunday As advised 10 The Lord sits enthroned over the flood; Today’s Readings the Lord sits enthroned as king for ever. 11 May the Lord give strength to his people! Collect of the Day May the Lord bless his people with peace! Eternal Father, who at the baptism of Jesus revealed him to be your Son, Second Reading Acts 10:34-43 anointing him with the Holy Spirit: Then Peter began to speak to them: “I truly understand that grant to us, who are born again by water and the Spirit, God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who that we may be faithful to our calling as your adopted fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him. -

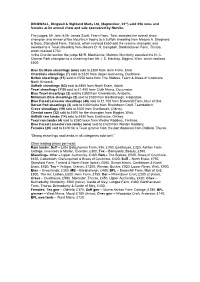

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts Ltd, (September, 23rd) sold 358 rams and females at its annual show and sale sponsored by Norvite. The judges, Mr John & Mr James Scott, Fearn Farm, Tain, awarded the overall show champion and winner of the Mountrich trophy to a Suffolk shearling from Messrs A. Shepherd & Sons, Stonyford Farm, Tarland, which realised £650 and the reserve champion was awarded to a Texel shearling from Messrs D. N. Campbell, Bardnaclaven Farm, Thurso, which realised £700. In the Cheviot section the judge Mr R. MacKenzie, Muirton, Munlochy awarded the N. C. Cheviot Park champion to a shearling from Mr J. S. MacKay, Biggins, Wick, which realised £600. Blue Du Main shearlings (one) sold to £500 from Hern Farm, Errol. Charollais shearlings (7) sold to £320 from Upper Auchenlay, Dunblane. Beltex shearlings (15) sold to £550 twice from The Stables, Fearn & Braes of Coulmore, North Kessock. Suffolk shearlings (63) sold to £850 from North Essie, Adziel. Texel shearlings (119) sold to £1,450 from Clyth Mains, Occumster. Blue Texel shearlings (2) sold to £380 from Greenlands, Arabella. Millenium Blue shearlings (2) sold to £500 from Bardnaheigh, Harpsdale. Blue Faced Leicester shearlings (46) sold to £1,100 from Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord. Dorset Poll shearlings (4) sold to £300 twice from Rheindown Croft, Teandalloch. Cross shearlings (19) sold to £600 from Overhouse, Orkney. Cheviot rams (32) sold to £600 for the champion from Biggins, Wick. Suffolk ram lambs (14) sold to £420 from Easthouse, Orkney. Texel ram lambs (4) sold to £380 twice from Wester Raddery, Fortrose. Blue Faced Leicester ram lambs (one) sold to £420 from Wester Raddery. -

What Happened to Notre Dame?

What Happened to Notre Dame? Charles E. Rice Introduction by Alfred J. Freddoso ST. AUGUSTINE’S PRESS South Bend, Indiana 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Charles E. Rice Introduction copyright © 2009 by Alfred J. Freddoso All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of St. Augustine’s Press. Manufactured in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Rice, Charles E. What happened to Notre Dame? / Charles E. Rice ; introduction by Alfred J. Freddoso. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-1-58731-920-4 (paperbound : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58731-920-9 (paperbound : alk. paper) 1. University of Notre Dame. 2. Catholic universities and colleges – United States. 3. Catholics – Religious identity. 4. Academic freedom. 5. University autonomy. 6. Obama, Barack. I. Title. LD4113.R54 2009 378.772'89 – dc22 2009029754 ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences - Permanence of Paper for Printed Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. St. Augustine’s Press www.staugustine.net Table of Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction by Alfred J. Freddoso xi 1. Invitation and Reaction 1 2. The Justification: Abortion as Just Another Issue 9 3. The Justification: The Bishops’ Non-Mandate 18 4. The Obama Commencement 25 5. ND Response 34 6. Land O’Lakes 42 7. Autonomy at Notre Dame: “A Small Purdue with a Golden Dome”? 54 8. -

St. Lukes, Merced Fr

Diocese of San Joaquin Calendar of Prayer January 1 – March 31, 2017 This booklet is offered to all who will pray daily for the people and the work of the diocese. A weekly calendar of prayers for the churches and clergy of San Joaquin is followed by a daily calendar of prayer following the Anglican Cycle of Prayer, with local requests included. The Calendar is published in each of the four Ember Seasons. Special events may be included in the next quarters Calendar upon request. This Calendar is also available on dioceseofsanjoaquin.net. God bless you richly in Christ Jesus, in whom all our Intercessions are acceptable through the Spirit. 1 2 DELTA DEANERY (Monday) St. Francis of Assisi Anglican Church, Stockton Fr. Woodrow, Gubuan Dcn. Jeff Stugelmeyer St. Mary the Virgin Anglican Church, Manteca Deacon Lee Johnson (Bob) St. Anselms, Elk Grove Cn. Franklin Mmor Dcn. Daniel Park (Joy) Fr. James Sweeney (Betsy) St. David’s, Fairfax Fr. Craig Isaacs (Mindy) Fr. Scott Mitchel (Linda) St. John’s, Petaluma Fr. David Miller (Betty) St. Mark’s, Loomis Fr. Carl Johnson (Catharine) Christ Church, Reno Fr. Ron Longero (Mimi) 3 SIERRA DEANERY (Tuesday) Trinity Memorial, Lone Pine Fr. J.P. Wadlin (Pam) Fr. Doulas Buchanan (Claudia) Dcacon Linda Klug St. Timothy's, Bishop Fr. J.P. Wadlin (Pam) St. Peter's, Kernville Deacon Tom Hunt Christ the King Anglican Church, Ridgecrest Fr. Townsend Waddill (Lisa) Deacon Judith Battershell Deacon Debby Buffum (Frank) St. Judes in the Mountains, Tehachapi Fr. Wes Clare (Wendy) Dcn. Dennis Mann (Trisha) St. Andrews, Lancaster Fr. -

Commemoration of Benefactors 1823

A FORM FOR TH E COMMEMORATION OF BENEFACTORS, TO BE USED IN THE CHAPEL OF TH E College of S t. Margaret and St. Bernard, COMMONLY CALLED Queens’ College, Cambridge. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY J. SMITH. M.DCCC.XX.III. THE SOCIETY OF QUEENS’ COLLEGE. 1823. President. H enry G odfrey, D. D. ( Vice-Chancellor). Foundation Fellows. J ohn L odge H ubbersty, M. D. G eorge H ew itt, B. D. Charles F arish, B. D. W illiam M andell, B. D. T homas Beevor, B. D. G eorge Cornelius G orham, B. D. John T oplis, B. D. J oseph J ee, M. A. Samuel Carr, M. A. J ohn Baines G raham, M. A. H enry V enn, M. A. J oseph D ewe, M. A. J oshua K ing, M. A. T homas T attershall, M. A. Samuel F ennell, B. A. Edwards’ By-Fellow. John V incent T hompson, M.A., F.A.S. A FORM FOR TH E COMMEMORATION OF BENEFACTORS, TO BE USED IN THE CHAPEL OF TH E College of St. Margaret and St. Bernard, COMMONLY CALLED Queens’ College, Cambridge. LET the whole Society assemble in the College Chapel, on the day after the end of each Term; and let the Commemoration Service be conducted in the following manner; as required by the Statutes, (Chapter 25. ‘ De celebranda memoria Benefactorum’ — ¶ First, the Lesson, E cclesiasticus X L IV , shall be read.—¶ Then, the Sermon shall be preached, by some person a appointed by the President; at the conclusion o f which, the names o f the Foundresses, and of other Benefactors, shall be recited: — I.