Macroberts on Scottish Construction Contracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design/Build and the Structural Engineer

A look at advantages and disadvantages Design/Build and the Structural Engineer By Joseph P. Watson III, P.E. Design/build definitely presents many advantages to participants in a project. First of all, design/build offers the owner a single source of responsibility—one contact point for all questions, conflicts, and revisions. Conflicts, questions, and problems can be addressed more easily because all of the players are on the same team. As an engineer, one of the things I like best about design/build is the problem-solving aspect. When a problem arises at job site, there is no finger-pointing to determine who’s at fault, which, under other project delivery systems, can take months of accusations and digging back through design files— even legal action in some cases—to determine. With design/build, the question is not “Whose fault is it?” but rather “O.K., we’ve got a prob- lem; what do we do to solve it”. Revisions can be handled much more smoothly under design/build, again because all affected parties – architect, engineers, and contractor – The Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office selected The Haskell Company especially for its design-build experience for the Falkenburg Road Jail in Tampa. The project is a five-building campus, consisting of a 44,000 s.f. reception are on the same team. Preliminary and operations center, two 50,000 s.f. dormitories with 256 beds each, a two-story 71,000 s.f. special management analysis can be worked up easily, housing facility with 256 beds, and an 8,000 s.f. -

The Bridge & Structural Engineer

The Bridge & Structural Engineer Indian National Group of the International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering ING - IABSE Contents : Volume 46, Number 4 : December 2016 Editorial ● From the Desk of Chairman, Editorial Board : Mr. Alok Bhowmick iv ● From the Desk of Guest Editor : Mr. P Surya Prakash vi Special Topic : Challenges Facing the Civil & Structural Engineering Industry 1. Challenges Facing the Civil & Structural Engineering Fraternity in India 1 Elattuvalapil Sreedharan, Mahesh Tandon 2. Role of Civil and Structural Engineers in Sustainable Built Environment 4 Subramanian Narayanan 3. Civil/Structural Engineering Education & Professional Practice in India : An Introspection 19 Manoj Mittal 4. Challenges for the Consulting Engineering Fraternity 23 Sayona Philip 5. Civil Engineers – Establishing Their Role 27 R. Gogia 6. Let’s Continue to Practice without Legislation for Engineers 32 Sudhir Dhawan 7. Engineering Design Services in India - Challenges Ahead 35 Amitabha Ghoshal 8. Challenges Facing Structural Engineers & Engineering Organizations 39 Alpa Sheth, Rajendra Gill 9. Ethics and Structural Design of Buildings 44 Sangeeta Wij 10. India’s Vision 2030 What Engineers & Technologists Can Do? 49 Ajit Sabnis CONTENTS 11. Developing the Next Generation of Civil Engineers – A Challenging Task Ahead 53 Alok Bhowmick Panorma ● Highlights of the ING-IABSE Seminar on “Urban Transport Corridors” held at 58 Visakhapatnam (Andhra Pradesh) on 21st and 22nd October, 2016 ● Message from Vice President of India 61 ● Message -

Structural Engineers Association of Northern California

575 Market Street, Suite 2125 | San Francisco, CA 94105-2870 email: [email protected] | 415-974-5147 www.seaonc.org Structural Engineers Association OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA Our mission: To advance the practice of structural engineering, to build community among our members, and to educate the public regarding the structural engineering profession. Our vision: A world in which structural engineers are valued by the public for their contributions to building a safer and stronger community. MARCH 2019 See our History, Mission Statement, and Bylaws for more information. Vol. XXII, No. 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE In the last year or so we have seen a number of high profile failures in President’s Message pp. 1-2 our infrastructure system here in the Bay Area. There was the leaning Upcoming Events pp. 2-5 skyscraper that made national news, the cracked steel beams that shut down a brand new transit center, and the hundreds of buildings that Committee News p. 5 burned down in wildfires. In the month of February alone, there was a major bridge shut down because of crumbling concrete and a major Job Forum pp. 7-15 highway shut down because of a levee breech. I can certainly think of better ways to celebrate National Engineers Week. All of this bad news can be discouraging to civil and structural engineers. After all, we design structures to withstand the forces of nature, not to succumb to them. People in our community depend on us to design safe and durable structures, so when a structure fails the public often reinforces the mindset that engineers are responsible for the failure when they ask us why we think something failed. -

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER – 5-10 Years of Experience Jarmel Kizel

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER – 5-10 Years of experience Jarmel Kizel Architects and Engineers, Inc. is a full service award winning Architectural and Engineering firm with offices in Livingston, New Jersey. At this time, our firm has an opening in our Structural Department for a Structural Engineer. We are in a growth mode and we are seeking quality talent to join our firm. We will accept resumes from engineers with 5-10 years of experience and skills as noted below. As a design engineer, you will work closely with the architectural project manager and have the opportunity to become involved in large and exciting projects. Experience Requirements PLEASE DO NOT RESPOND TO THIS ADVERTISEMENT UNLESS YOU HAVE THESE QUALIFICATIONS, YOU MUST HAVE PROPER EXPERIENCE. Bachelor of Science degree in Civil/Structural Engineering 5+ years of experience relevant structural design experience Analysis and design of buildings and similar structures Thorough knowledge of current building codes and standards, including IBC and ASCE 7 Perform and document structural calculations for all applied loading, including gravity and lateral loads Design of steel, concrete, masonry, and wood structures Coordination with architects and other engineering disciplines to develop complete design drawings Site visits for measuring and documenting existing buildings and structures for further analysis and drawing production Development of structural drawings and technical specifications Site visits during construction to review progress of construction Good written and Verbal skills for report preparation and client interaction Experience with AutoCAD 2014 or newer and RAM structural design software Educational Requirements: Bachelor Science in Civil/Structural Engineering. Masters in Structural Engineering a plus. -

Structural, Geotechnical and Earthquake Engineering - Sashi Kunnath

STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING AND GEOMECHANICS - Vol. I - Structural, Geotechnical and Earthquake Engineering - Sashi Kunnath STRUCTURAL, GEOTECHNICAL AND EARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING Sashi Kunnath University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Keywords: structural analysis; structural design; earthquake engineering; geotechnical engineering; seismic protection; structural engineering Contents 1. Introduction 2. Structural Engineering 2.1. Brief Historical Perspective of Structural Analysis and Engineering 2.2. Linear and Nonlinear Analysis of Structures 2.3 Structural Design 2.4 Emerging Developments in Structural Engineering 3. Geotechnical Engineering 3.1. Foundation Design 3.2. Modeling and Analysis 4. Earthquake Engineering 4.1. Seismic Resistant Design 4.2. Recent Advances in Earthquake Engineering 5. Concluding Remarks Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary An overview of essential topics in structural and geotechnical engineering with particular focus on those related to earthquake engineering is presented. One of the objectives of this introductory chapter is to eventually provide readers with insights into seismic analysis and design. Beginning with a brief history of structural engineering, topics in structural analysis and design are reviewed. This is followed by a brief overview of geotechnical engineering with emphasis on foundation design and modeling for geotechnical applications. The final section focuses on earthquake engineering covering both structures and foundations and highlighting both traditional seismic design and innovative seismic protection. 1. Introduction The subject areas that encompass structural, geotechnical and earthquake engineering can all be regarded as topics within the broad field of civil engineering. While structural engineering focuses on the design of the visible part of a finished structure, geotechnical engineering is concerned with the design of the structural foundation below the soil surface. -

Structural Engineering Overview CEE 379 Structural Engineering Overview Notes

Structural Engineering Overview CEE 379 Structural Engineering Overview Notes What do structural engineers do? Structural engineers have the responsibility of designing structures and structural components so that they are sufficiently strong, stiff, stable, and safe to meet client needs. For a structure to be sufficiently strong, it must be able to handle normal loads without sustaining noticeable damage. To be sufficently stiff, a structure should not deform under loading in ways that cause discomfort or distress to occupants/users or contents/equipment. Stability is related to strength, but it refers to particular kinds of failure that are not initiated by localized overstressing of material, but rather by phenomena driven by nonlinear feedback between load and deformation, such as buckling or overturning. For a structure to be safe, it should be able to handle extreme loadings in such a way that occupants have time to exit prior to collapse. Structural engineers typically work as part of a team that might include architects, contractors, fabrica- tors, building officials, and numerous other engineering disciplines. Although a great deal of the educational focus for structural engineering revolves around analysis and design code calculations, in practice one must bring to the table an ability to work creatively in a team context to solve problems. Structural engineering requires a great deal of technical depth, but structural engineers are professionals, not technicians. Note that it is possible (and not uncommon) for the structural engineer to perform his or her job well, but for the structure itself to not succeed. A building can be ugly, drafty, or toxic, it can block views, it can go out of style, and so on. -

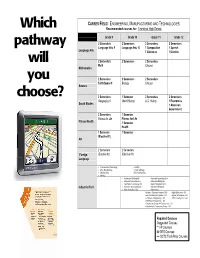

Tech- Engineering, Manufacturing & Technologies

CAREER FIELD: ENGINEERING, MANUFACTURING AND TECHNOLOGIES Which Recommended courses for: Technical High School Grade 9 Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 pathway 2 Semesters 2 Semesters 2 Semesters 2 Semesters Language Arts 9 Language Arts 10 1 Composition 1 Speech Language Arts 1 Literature 1 Elective will 2 Semesters 2 Semesters 2 Semesters Math Choose Mathematics you 2 Semesters 2 Semesters 2 Semesters Earth/Space 9 Biology Choose Science choose? 2 Semesters 1 Semester 2 Semesters 2 Semesters Geography 9 World History U.S. History 1 Economics Social Studies 1 American Government 2 Semesters 1 Semester Fitness for Life Fitness for Life Fitness/Health 1 Semester Health 1 Semester 1 Semester (Elective #1) Art 2 Semesters 2 Semesters Foreign (Elective #2) (Elective #1) Language Communication Technology Drafting A/B – Woodworking Power & Energy Woodworking Electricity/Robotics Welding Architectural Drafting A/B Advanced Automotives B++ Advanced Automotives A++ Advanced Welding A++ Construction Technology A/B Digital Photography A/B Industrial Tech Advanced Woodworking A/B++ Advanced Welding B++ Video Productions A/B Automotives Brakes – Discovery Academy (DA) Digital Electronics - DA Electrical/Electronic System – DA Engine Performance - DA Principals of Engineering – DA CISCO Routing I & II - DA Steering and Suspension – DA Engineering Design and Development – DA Introduction to Engineering Design – DA Required Courses Suggested Courses ** AP Courses ## SRS Courses ++ SCTC Tech Prep Courses Potential Careers in the Engineering, Manufacturing and Technologies Career Pathway Do you like to: Work in math and physical science areas? Use problem-solving skills and use logic? Use oral and dissect similar pieces from the big picture? Work with critical details? People attracted to careers in this pathway like to work with things. -

Cobeen, Kelly

PERSONNEL QUALIFICATIONS WJE Kelly E. Cobeen | Principal EXPERIENCE Seismic Evaluation Kelly Cobeen joined WJE in 2008 with twenty- ◼ Old Solano Courthouse - Fairfield, CA: three years of experience in structural design, Seismic upgrade study of 1910s steel frame working in a wide range of project types, sizes, building with masonry infill* and construction materials. She has a special ◼ Santa Margarita Adobe - Camp Pendleton, interest in seismic resistance of light-frame CA: Schematic seismic upgrade for adobe residence with nonductile concrete and construction, applicable to new construction hollow clay tile* and seismic upgrade of existing buildings. ◼ University of California, Berkeley, Haas Clubhouse at Strawberry Canyon: Schematic Ms. Cobeen has been involved in numerous seismic upgrade* code development, research, and educational activities. Her code development activities Seismic Upgrade Design include involvement in the NEHRP ◼ ATC 66: Seismic Rehabilitation Training for Recommended Provisions for Seismic One- and Two-Family Woodframe Dwellings, EDUCATION Regulations for New Buildings as well as training developed with Applied Technology ◼ University of California, Berkeley International Building Code and International Council* ◼ Bachelor of Science, Civil Residential Code development. Her educational ◼ University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall Engineering, 1983 activities include coauthoring the Design of Annex: Voluntary seismic strengthening* ◼ Master of Science, Civil Wood Structures textbook, teaching wood ◼ California -

Engineering Employme

E3 Employer - Current Positions Attending employers are recruiting for the following jobs in the following disciplines: Hiring Organization Current Positions Disciplines Business Development Buiding/Chemical/Mechanical / Industrial/ Pliteq Inc Engineering Junior R&D Associate Robotics/Structural Stationary Engineer Production Millwright positions Chemical/Electrical/Electronics/ Mechanical / GlaxoSmithKline Industrial / Robotics PERI Formwork Systems Inc. Designer/EIT Civil Site Engineers Mechanical & Electrical Coordinators/specialists Project Coordinators QA/QC Professionals Building/Civil/Mechanical/Industrial/ Eastern Construction Project Superintendents (strong Engineering background/knowledge is required) Robotics/Structural Project Managers Coordinator Construction Services Technical Specialist Project Management Coordinator Building/Civil /Electrical/Electronics/ Defence Construction Canada Environmental Services Coordinator Mechanical / Industrial / Facility Management Robotics/Environmental/Clean Tech Design Engineer Control system Engineer Computer / IT / Systems Design / Software/ I&C Engineer Electrical / Electronics/Mechanical/Industrial/ Alithya Digital Technology Corporation Process Control Engineer Robotics/Nuclear/Oil/Petroleum/ Automation Engineer Water/Wastewater E.I.T - Land Development E.I.T - Water Resource Crozier & Associates Consulting Jr & Sr Design Technologist Building/Civil/ Engineers Field Technologist Structural/Transportation/Water/Wastewater Project Manager Transportation Structural Engineer/Mechanical -

Your Home Project Guide to Appointing a Structural Engineer

Your Home Project Guide To Appointing A Structural Engineer istructe.org/building-confidence istructe.org/building-confidence 1 Published by The Institution of Structural Engineers International HQ 47-58 Bastwick Street, London EC1V 3PS, United Kingdom Telephone: +44(0)20 7235 4535 Email: [email protected] Website: www.istructe.org First published 2015 ISBN 978-1-906335-28-1 © 2015 The Institution of Structural Engineers Appointing a Structural Engineer for your Domestic Project A homeowners’ guide to renovations, extensions and new builds About this guide Whether you are planning to build a new home or perhaps modify, extend or refurbish an existing property you will have great hopes and aspirations for a successful project. The construction industry is complex and you may be feeling at least a little daunted by all that will be involved in achieving your dream. This guide has been produced by The Institution of Structural Engineers, which is a professional organisation incorporated by Royal Charter, recognised globally for its rigorous entrance examinations for those who wish to become members. Throughout their career Institution members must continue to study and demonstrate professional development so that their knowledge and skills remain up to date. The Institution has endeavoured to ensure the accuracy of this guide, however the comments made must be taken as general guidance and readers should take specialist advice on the specific projects being considered or undertaken. Introduction Building work needs to comply with a lot of regulations and legal obligations. Whilst information on roles and responsibilities of the structural engineer are common across the UK it is important to remember that the rules you must follow might not necessarily be the same in Scotland and Northern Ireland as in England or Wales. -

What Kinds of Engineers Build Bridges? What Do Civil Engineers Do?

What kinds of engineers build bridges? What do civil engineers do? Civil engineering focuses on structures that serve the public such as transportation systems, water treatment, government buildings, public facilities such as airports and train stations, and other large-scale projects that benefit the public. A civil engineer must be able to design safe structures in various locations. In terms of transportation, civil engineers build bridges, tunnels, freeway interchanges, and other structures that are designed to facilitate the smooth, even flow of traffic. Water treatment includes sewage plants, delivery systems for freshwater and dams, and other facilities that deal with both fresh- and wastewater. Government buildings can include courthouses and libraries, and a civil engineer might also work on a city power plant. Some of the subspecialties in civil engineering are environmental engineering, coastal engineering, surveying, materials engineering, structural engineering, construction engineering, and water resource engineering. What do structural engineers do? Structural engineers are specialists in design, construction, repair, conversion, and conservation. They are concerned with all aspects of a structure and its stability and safety. Structural engineering is considered a subspecialty of civil engineering. Structural engineers are a key part of the design and construction team, working alongside other engineering disciplines to create all kinds of structures, from houses, theaters, sports stadiums, and hospitals, to bridges, oil rigs, and space satellites. They also consider the aesthetics of the site and the community in which it will be built. Every structure must be built with consideration of the conditions of the its location. Bridges in cold, snowy climates will need to be built with continuous snow and ice loads in mind. -

Developing the Next Generation of Structural Engineers

STRUCTURAL FORUM opinions on topics of current importance to structural engineers Developing the Next Generation of Structural Engineers Part 1: A Crisis of Opportunity Note: is is the rst article of a four-part series on the opportunities and challenges we face in By Glenn R. Bell, P.E., S.E., SECB developing the next generation of structural engineers. It is based on the author’s keynote address at the SEI Structures Congress in March 2012. A Crisis of Opportunity opportunities in this changed world. e approaches. It also requires that engineers take A year ago, I was invited to join the SEI Young massive population in developing countries leadership roles in major policy questions in Professionals Committee, which is addressing will need aordable, sustainable housing and hazards management, or even in some cases issues of interest to future generations of struc- infrastructure on an enormous scale. ere is advising societies on where not to build. tural engineers. e members of this committee a lot of building to be done! have concerns that I share… Our business is No. 5: Complexity becoming commoditized as computers and soft- No. 2: Globalization ware are doing more of our work. We face the Our large-scale civil/structural systems are threats of global outsourcing and competition. In the future, our workplace will be worldwide. becoming increasingly complex, and lessons Increasingly, we are having trouble attracting e global engineering workforce will be leveled. from recent natural disasters like Katrina and retaining the best and brightest to our We already face oshore competition, much of and Fukashima Daiichi have pointed out profession.