Golden Threshold,The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modular Infotech Pvt. Ltd

Committee for the Reorganisation of Edu~tion in the Hyderabad State REPORT OF 1HE SUB-COMMrrI'EE . ·A. H. Mackenzie. M.A., D.Litt., C.S.I., C.lE. Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Osmania UnirJersily and Fazl Muhammad. Khan, . Diredor of Public Inslrudion Hyderabad Slale . AA amended and approved by the Committee HYDERABAD-DECCAN AT THE GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS 1936 T.225.N36t G6 063256 SERVANTS OF INDIA SOCIETY'S LIBRARY, POONA 4,· FOR INTERNAL CIRCULATION To be returned 00. or beCore the last date stamped below 2 8AUG 196 Committee for the Reorganisation of Edu~iOiilii the· Hyderabad State REPORT OF THE SUB-COMMIlTEE A. H. Mackenzie. M.A., D.Liu., C.S.I., C.I.E. Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Osmania University and F azl Muhammad Khan, Director of Public Instruction Hyderabad Stale As amended and approved by the Committee HYDERABAD.DECCAN AT THE COVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS 1936 APPENDICES. 13 APPENDIX A. Names of Officers and Representatives to whom the Circular and Addresses were sent for opinion. (1) Lt.-Col. Sir R. H. C. Trench. Kt .• C.I.E. (2) Nawab Sir Ameen Jung Bahadur. (3) " Hasham Yar Jung Bahadur. (4) " Ali Nawaz Jung Bahadur. (5) " Yasin Jung Bahadur. (6) Moulvi Abdul Rahman Khan Sahib. (7) Nawab Mirza Yar Jung Bahadur. (S) " Fakhr Yar Jung Bahadur. (9) Subedar Sahib, Aurangabad. (10) " "Gulbarga. (11) " "Medak. (12) " "Warangal. (13) 1st Taluqdar, Aurangabad. (14) " " Parbhani. (15) " " N anded. (16) " " Medak. (17) " " Nizamabad. (IS) " " N algonda. (19) " " Mahboobnagar. (20) " " Gulbarga. (21) " ,,' Raichur. (22) " " Osmanabad. (23) " " Bidar. (24) " " Warangal. (25) " " Kareemnagar. (26) " " Asifabad. (27) " " Bir. -

The Bahmanis of Gulbarga

A Study of Communal Conflict and Peace Initiatives in Hyderabad: Past and Present Conducted By COVA Research Team: M.A. Moid Shashi Kumar B. Pradeep Anita Malpani K. Lalita Supervision Mazher Hussain In Collaboration with Aman Trust, New Delhi 2005 Part I Communal Conflict and Peace Initiatives in Hyderabad Deccan: The Historical Context Research: M.A. Moid In the last decade or so, communalism has come be a major issue of concern when examining the Indian social fabric. Many efforts have been made to understand the various nuances of the problem. While the roots of present-day communal conflicts and riots could be traced to socio-economic and political causes, communalism has its roots in history. Colonialist policies, modernization, mass politics, competition, identity and culture are the different facets of this debate. In Hyderabad, Hindu-Muslim relations have a long history, spread over four centuries. The immediate history of the last five decades is particularly significant to understand the issue of communalism in Hyderabad. In the following pages, an attempt has been made to trace the roots of the communal conflict in Hyderabad. Some basic questions sought to be answered are: How did the Muslims arrive in Deccan? How was their settling down in the South different from their engagements in North India? How did the Hindus react to the new arrivals? How did the Muslims become a part of the Deccan and how did a composite culture develop? The study is divided into five parts. Part I is about the first Muslim kingdom of the South, covering Allauddin Khilji’s arrival and Mohammed Bin Tughlaq's involvement in the Deccan, up to the establishment of the Bahmani Kingdom and its achievements. -

Notification No 0123.Pdf

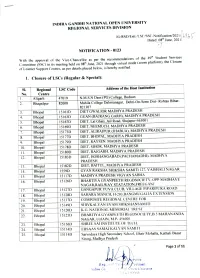

UNIVERSITY INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL OPEN REGIONAL SERVICES DIVISION IG/RSD/Estt./L.SC/SSC-Notification/2021/ 6S Dated: 08" June. 2021 NOTIFICATION - 01233 of the 49" Student Services of the Vice-Chancellor as per the recommendations With the approval the Closure virtual mode (z0om platform). Cmmittee (SSC) in its mecting held on 08h June, 2021 through notified. ofLearner Support Centres, as per details placed below, is hereby 1. Closure of LSCs (Regular & Special): Address of the Host Institution SI. Regional LSC Code No. Centre 47019 N.M.S.N Dass (PG) College, Budaun Aligarh Dist- Rohtas Bihar Bhagalpur 82008 Mahila College Dalmianagar, Dehri-On-Sone 821307 DIET GWALIOR MADHYA PRADESH Bhopal 15161D Bhopal 15163D GUAN (BAJRANG GARH), MADHYA PRADESH Bhopal 15167D DIET, Lal Ghati, Jail Road, Shajapur-465001 PRADESH Bhopal 15169D DIET, NEEMUCH. MADHYA MADHYA PRADESH Bhopal | 15173D DIET, ALIRAJPUR (JHABUA), DIET, BHOPAL, MADHYA PRADESH 8. Bhopal 15177D MADHYA PRADESH 9. Bhopal 15179D DIET, RAYSEN. DIET, SIHOR, MADHYA PRADESH 10. 15178D Bhopal DIET, RAJGARH, MADHYA PRADESH 11. Bhopal 15180D MADHYA 12 Bhopal 15183D DIET, HOSHANGABAD (PACHAMADHI). PRADESH DIET, BAITUL, MADHYA PRADESH 13. Bhopal 15182D VAISHALINAGAR 1559D GYAN RAKSHA SHIKSHA SAMITI 127, Bhopal MADHYA PRADESH VIGYAN SABHA 15 Bhopal 15117D REGDSOCIETY, OPP MADHAVE 16 Bhopal 15126D BHARTIYA GYANPEETH NAGAR,RAILWAY STATATION.FREEGANJ GANGAPUR YUVA CLUB, VILLAGE PIPARIPURA ROAD 17. Bhopal 15127D SAHARA MANCH, H-203,BANGMUGALIA EXTENsION 18. 15128D Bhopal COMPOSITE REGIONAL CENTRE FOR 19. Bhopal 15137D 20 Bhopal 15149D SHIVKALYAN EVAM SHIKSHANSAMIT Bhopal 15120D K.G. NATIONAL MEMORIAL TRUST REGDSOCIETY,B 5 MAHANANDA 22. Bhopal 15125D BHARTIYA GYANPEETH NAGAR, UJJAIN, M.P- 456001 SHREE SAI INSTITUTE OF TECH. -

Darpan-Proof-2014-15.Pdf

History Established in 1887 by the amalgamation of Hyderabad School and the Madarsa- i-Aliya, Nizam College is one of the oldest and most esteemed institutions of higher education in South India. It was affiliated to the University of Madras for 60 years after its inception, and was made a Constituent College of Osmania University on 19th February 1947. Dr. Aghornath Chattopadhyay , father of Sarojini Naidu, was the founder principal of the College .The college was first granted Autonomous Status for Undergraduate Courses by the UGC in 1988-89 and has already completed 25 successful years of autonomy. The stalwart principals who steered the college towards the summit of success before independence: P H Hudson (1888-95), A Seation (1895-11) , P H Sturge (1911-18) ,K. Burnett (1919-29) , B.C. Mc Ewen(1930) , W. Turner (1930-37), Qadin Hussain Khan (1938-43) , Syed Ali Akbar (1943-45) , Harron Khan Sherwani( 1945-46) Principal Vision and Mission k To continue as a center of excellence in education and research and consolidate our position as a reputed institution of higher education in the country. k To enhance the standing of the College as a preferred institution of higher education both among the national and international student community. k To provide students with a teaching-learning experience that develops in them the capacity for creativity, critical evaluation, discernment, effective communication, in-depth knowledge and fashion them into innovators, leaders and entrepreneurs. k To enhance industry-academy interaction and involve eminent Prof. T.L.N. Swamy persons form the industry as resource persons, invite them for guest Department of Economics lectures, and arrange internship for students in industries. -

Dr. P. Muralidhar Reddy M.Sc., Ph.D Assistant Professor of Inorganic Chemistry Email: [email protected], [email protected]; ______

Dr. P. Muralidhar Reddy M.Sc., Ph.D Assistant Professor of Inorganic Chemistry Email: [email protected], [email protected]; ________________________________________________________________ Dr. P. Muralidhar Reddy is working as Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry, Nizam College, Osmania University since 2013. He has received B.Sc., M.Sc., and Ph.D. in chemistry from Kakatiya University, Warangal, Telangana State, India. Dr. P.M. Reddy worked as a visiting faculty member at Tzu Chi University, Hualien for two months in 2014. He also worked as Postdoctoral Fellow (PDF) at National Dong Hwa University (NDHU), Taiwan from August 2007 to September 2013. During this period, he has focused on the synthesis, characterization of nanoparticles towards biological applications and identification of the microorganisms by electrospray ionization (ESI)/Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry techniques. During the period of his doctoral research work (2002 to 2006), he has developed various methodologies in Inorganic and Analytical chemistry. He also has Industrial Experience in Analytical Research and Development (AR&D), Hetro Drugs Limited (R&D), Hyderabad, India. Dr. Reddy has published over 60 Research Papers in reputed International and National Journals (Citations: 930, h-index: 18, i10index: 27) and one patent to his credit. He has also presented research papers in 50 National and 25 International conferences. He has delivered guest/invited lectures in various colleges/conferences. He is a Life member of Indian Council of Chemists (ICC), Indian Science Congress Association (ISCA), India and Member of Taiwan society for mass spectrometry (TSMS), Taiwan. He is a reviewer for over 15 National and International professional journals. -

Dr. C. V. Ranjani, Conference Secretary, Email: [email protected];

Chief Patron Conference Advisory Committee Prof. S. Ramachandram Prof. H. Venkateshwarlu Hon’ble Vice Chancellor, OU, Hyderabad Special Officer, OU Centenary Celebrations Patron Prof. K. Shankaraiah, Prof. Syed Rahman Dean Faculty of Commerce Principal, Nizam College, Hyderabad Prof. Ch. VenkataRamana Devi Dean Faculty of Sciences, OU Conference Director Prof. T. Parthasarathy, Dean, UGC (OU) Dr. S. Balabrahma Chary Prof. V. Anand Kumar, Head, Commerce, OU Vice- Principal, Nizam College, Hyderabad Prof. J. Siva Kumar Mobile: +919290048551 Head, Dept. of Physics, OU Conference Secretary Prof. M. Devadas Head, Dept. of Chemistry, OU Dr. C. V. Ranjani Prof. H. Ramakrishna Head, Department of Commerce Head, Dept. of Botany, OU Nizam College, Hyderabad. Prof. Shiva Raj, Principal, UCS, OU Mob: +919247541936 Prof. B. Narayana Conference Convener Dept. of Economics, Nizam College Dr. P. Hima Bindu Prof. K. Srinivasulu Head, Department of Physics Dept. of Political Science, Nizam College Nizam College, Hyderabad International Advisory Committee Mobile: +919603120775 Conference Co-Conveners Prof. Yen-Peng Ho National Dong Hwa University, Taiwan. Prof. M. Gangadhar Prof. Anren Hu, Tzu Chi University, Taiwan. Dept. of Commerce. Prof. Sreekanth B J Dr. B. Sireesha University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Head, Dept. of Chemistry Prof. Utz Fischer Dr. A. Vijaya Bhaskar Reddy Julius Maximilian University, Würzburg, Germany. Head, Dept. of Botany - 9440747620 Dr. Ronald E. Tosh, NIST, Maryland, USA. Ms. S. Renuka Dr. Chetan Maringanti Head, Dept. of Mathematics - 9573654252 Credit Suisse, Zurich, Switzerland. Conference Coordinators Dr. V. Bharath Kumar, Dr. P. Aruna Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Head, Dept. of History - 9440643655 Mr. -

Special Article Open Access

Pandey. Space and Culture, India 2015, 3:1 Page | 17 SPECIAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Changing Facets of Hyderabadi Tehzeeb: Are We Missing Anything? Dr Vinita Pandey† Abstract In its historic evolution and development, the Hyderabad city has experienced many changes since its foundation as the capital of the medieval Kingdom of Golconda in the 16th century to its present status as the metropolis of a modern state. Each historic phase of development has significantly influenced its physical, social, economic and cultural growth. Hyderabad, under the influence of Deccan, Persian and indigenous culture, synthesised and evolved its very own Hyderabadi Tehzeeb. It truly represented the assimilation (yet uniqueness) of diverse cultures which inhabited Hyderabad. More than four hundred years later, HITEC city Hyderabad today presents a different picture. Whether it is its structural and spatial expansion, infrastructural development or its socio-cultural ethos, contemporary Hyderabad has evolved phenomenally and for many natives beyond recognition. Using ethnographic approach and secondary data, the paper introspects whether the City of Pearls has retained its unblotted tolerance and Hyderabadi Tehzeeb or has given up to the challenges of modern and globalizing times. Culturally, what is it that the natives of ‘Bhagyanagar’ irrespective of their caste, creed, gender, region and religion miss in modern Hyderabad. Key words: Culture (Tehzeeb), Hyderabad, Ganga-Jamuna Tehzeeb (Hindu-Muslim culture), Social Changes and Cultural diversity, India † Department of Sociology, Nizam College, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana, India Email: [email protected] Pandey. Space and Culture, India 2015, 3:1 Page | 18 Introduction architecture with Persian elements of arches, Cities evolve with people of multiple cultures domes and minarets. -

Alumni Association of Osmania University -Souvenir

Alumni Association of Osmania University -Souvenir AlumniAlumni dayday -- 2929 DecemberDecember 20072007 BackBack toto roots...roots... GiveGive backback Vision Farman of H.E.H. Nizam VII 26th April, 1917 “ I am pleased to express my approval of the views set forth in the Arzdasht (petition) and the memorandum submitted there- with, regarding the establishment of a University for the State, in which the knowledge and culture of Ancient and Modern times may be blended so harmoniously as to remove the defects created by the present system of education and full advantage may be taken of all that is the best in Ancient and Modern systems of physical, intellectual, and spiritual culture. In knowl- edge, it should aim at the moral training of the students and give an impetus to research in all scientific subjects. The fun- damental principle in the working of the University should be that Urdu should form the medium of instruction in higher education but knowledge of English as a language should at the same time be deemed compulsory for all students. With this objective in view, I am pleased to order that steps be taken for the establishment on the lines laid down in the Arzdasht (petition) of a University for the Dominions to be called the Osmania University of Hyderabad in commemoration of my accession to the throne”. 2 Alumni Association of Osmania University -Souvenir Alumni day - 29 December 2007 Back to roots... Give back 3 4 PREFACE I am indeed happy that the Osmania University in its onward march of progress has completed 89 years. -

Republic of India. a Study of the Educational System of India

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 054 021 SO 001 525 AUTHOR Sweeney, Leo J. TITLE Republic of India.A Study of the Educational System of India & Guide to the Academic Placement of Students from India in United States Educational Institutions. INSTITUTION American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, Athens, Ohio. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 395p.; World Education Series AVAILABLE FROM Executive Secretary, American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, One Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C. 20036 ($1.00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS Academic Records, Administrator Guides, *Admission (School), *Comparative Education, Credentials, *Degree Requirements, Degrees (Titles), Educational History, Educational Trends, Elementary Education, Evaluation Methods, General Education, Higher Education, *School Systems, Secondary Education, Student Evaluation, *Student Placement, Technical Education, Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS Educational Systems, *India ABSTRACT The purpose of this publication, as in the case of the other "World Education Series", is to provide a guide for the use of admissions officers and others in the admission and placement of the students of a particular country for study in educational institutions in the United States. Specifically it is hoped that this volume will furnish the basis of sounder assessment of the quantity and the quality aspects of Indian educational institutions, and the Indian student and his academic record. The first seven chapters provide a description of the -

Muslim Belonging in Secular India: Negotiating Citizenship in Postcolonial Hyderabad Taylor C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09507-6 - Muslim Belonging in Secular India: Negotiating Citizenship in Postcolonial Hyderabad Taylor C. Sherman Index More information Index A.N. Shah, 93 B. Ramakrishna Rao, 48, 51, 111, 124, 126, Abdul Majid Khwaja, 178 129, 143, 163 Abdul Qadir, 39 medium of instruction, 161 Abdullah Bukhari, 85 state patronage, 82 Abul Kalam Azad, 50, 53, 57, 77, 160, 178 B.N. Nigam, 94 medium of instruction, 163 B.S. Venkat Rao, 6, 24 state patronage, 81–2 Badam Yella Reddy, 113 Aden, 65, 71 Badshahi Ashoorkhana, 111 state patronage, 87 Bahmani sultanate, 107 Adilabad, 137 Baitul Mazureen, Hyderabad, 79 Afghanistan, 56, 60, 65, 74, 80 Baker Ali Mirza, 25, 48, 129 Afghans, 73–4, 183 belonging, 22, 47–8, 87, 180–1 anti-Muslim violence, 33–4 economic, 91, 114–16 prisoners, 62 linguistic, 148–9, 168 repatriation, 67–9 mulki agitation, 114 Ahmed Mirza, 25 Benares Hindu University, 77, 80, 161, 164 Ahmed Mohiuddin, 144 Bengal, 7, 93 Akali Dal, 145 Bharatiya Janata Party, 179 Akbar Ali Khan, 29, 47–8, 50, 53, 129 Bhopal, 57, 85, 177 Ali Yavar Jang, 129 Bidar, 29, 41, 43, 50, 141 Aligarh Muslim University, 60, 76, 80, 164, Bir, 29 177 Bombay, 93–4 Allahabad, 116 British Empire All-India Bee Keepers Association, migration within, 59–60 77 Burma, 133 All-India Religious Leaders Association, 140 All-India Shia Conference, 136 Canada, 133 Andhra, 114 census, 154–5 Andhra Mahasabha, 133 mother tongue data, 150–1, 168 Andhra Pradesh, 172 multilingualism data, 151 Urdu, 178 census 1941, 6 Andhra University, 80 Central College -

College Report 2013-14

37th ANNUAL DAY 2013-14 (03-02-2014) LOYOLA ACADEMY DEGREE AND PG COLLEGE ALWAL, SECUNDERABAD-500 010. Inclusive, good-quality education is a foundation for dynamic and equitable societies. Desmond Tutu Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. On behalf of Loyola Academy, I extend a warm welcome to the honourable chief guest Mr. B. Prasada Rao, DGP Andhra Pradesh, and the respected guest of honour Dr. M. V. Rao, Director General, NIRD, for taking time out of their busy schedules to grace the occasion of the 37th Annual Day Celebrations of the college. I would also like to extend a very warm welcome to the Rev. Fathers, Brothers, Sisters, Parents, well-wishers and the media personnel for their presence in our midst today. Unique achievement Loyola Academy Degree and PG College with its highest NAAC score of 3.50 out of 4 is honored to be one among the 45 colleges across India to be chosen by the UGC to be elevated to attain the University status. After days of relentless effort, the Report has been submitted to the UGC which is now processing our request. God willing, we shall soon attain University status which will spur us on to achieve greater heights. Staff Achievements Dr. A. Raja Reddy, Reader in Agriculture Science, received the State Best Teacher award on the occasion of Teachers’ Day on 5 September 2013 at Rabindra Bharathi, Hyderabad. 1 Mr. B. Bhaskar Rao was awarded a cash prize of Rs.15000 in the 13th State level Painting and Sculpture Competition 2013 organized by Potti Sreeramulu Telugu University, Hyderabad. -

NIZAM COLLEGE Autonomous and Constituent College of Osmania University with CPE Status

NIZAM COLLEGE Autonomous and Constituent College of Osmania University with CPE Status ACTIVITIES TO ADDRESS LOCATIONAL ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES; ENGAGEMENT WITH AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO LOCAL COMMUNITY 2013-18 Nizam College organizes several programmes involving local community and also contributing towards community development. The geographical location of the College is extremely advantageous for success of such programmes. To mark the Independence Day celebrations “Save Life-Donate Blood” initiative was taken up for blood donation on 14th August, 2013. There is constant need of blood for leukemia patients in govt cancer hospital nearest to the college including MNJ cancer hospital. The same initiative was also taken up in August, 2014 and August, 2016 to commemorate India’s independence. Since Nizam College is at a geographically advantageous position, it facilitates contribution to community needs. Enhancing Green Cover and addressing Climate Change is very significant. To address this Harithaaram is being organized every year usually with the onset of Monsoon. The tree saplings are planted in collaboration with Council for Green Revolution. Since College is very popular with morning walkers, enhancing green cover also strengthens the lung space. In Harithaaram even neighbourhood community is involved. In 2017 the Bio-Diversity Club of Nizam College planted 30 varieties of medicinal plants in association with Telangana State Medicinal Plant Board. Some of these plants are also used by students for research. Interestingly the College has also collaborated with Telangana State Police for sapling plantation programme. This collaborative activity has also facilitated in projecting ‘people friendly, environment friendly police’. Padhao Badhao initiative involves collection of books and stationary from staff, students and community members to support the orphanages (Abhi Sai data Orphanage) and students of marginalized communities.