Locating the Auteur in Rituparno Ghosh's Dahan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postcolonial Resistance of India's Cultural Nationalism in Select Films

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 25 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies ISSN: 2456-7507 <postscriptum.co.in> Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed Volume V Number i (January 2020) Postcolonial Resistance of India’s Cultural Nationalism in Select Films of Rituparno Ghosh Koushik Mondal Research Scholar, Department of English, Visva Bharati Koushik Mondal is presently working as a Ph. D. Scholar on the Films of Rituparno Ghosh. His area of interest includes Gender and Queer Studies, Nationalism, Postcolonialism, Postmodernism and Film Studies. He has already published some articles in prestigious national and international journals. Abstract The paper would focus on the cultural nationalism that the Indians gave birth to in response to the British colonialism and Ghosh’s critique of such a parochial nationalism. The paper seeks to expose the irony of India’s cultural nationalism which is based on the phallogocentric principle informed by the Western Enlightenment logic. It will be shown how the idea of a modern India was in fact guided by the heteronormative logic of the British masters. India’s postcolonial politics was necessarily patriarchal and hence its nationalist agenda was deeply gendered. Exposing the marginalised status of the gendered and sexual subalterns in India’s grand narrative of nationalism, Ghosh questions the compatible comradeship of the “imagined communities”. Keywords Hinduism, postcolonial, nationalism, hypermasculinity, heteronormative postscriptum.co.in Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed ISSN 24567507 5.i January 20 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 26 India‟s cultural nationalism was a response to British colonialism. The celebration of masculine virility in India‟s cultural nationalism roots back to the colonial encounter. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Rabindrnath Tagore's Nauka Dubi - from Page to Screenn Prof

Rabindrnath Tagore's Nauka Dubi - From Page to Screenn Prof. Shailee Dhamsania A journey of a literary work fiom page to screen makes adaptation interesting. The adaptation of print medium into film took place for certain reasons. Firstly, the director gets fascinated by the story and believes the story lends itself beautihlly to the medium of film. Secondly, many a time he wishes to present his personal interpretation of the original story through his own language of film. Thirdly, he wishes to take up the challenge of recreating a period in history, and the original literary source is picked up mainly for the period element than for its theme of plot. Fourthly, he would like to use film because the story as literature reflects it, is in some way or another his own ideological stand on a particular subject or issue, and his use of the film medium conveys this ideology to his audience. Rabindranath Tagore is a milestone in Bengali literature. With the publication of Gitanjali, his fame attained a luminous height taking him across continents. For the world he became the voice of India's spiritual heritage; and for India, especially for Bengal he became a great living institution. Tagore was philosophic, spiritual and experimental in his expression. He was more inclined to poetry but contributed and enriched all most all forms of art and literature. There is no exaggeration if we call him the best literary stalwart of India. His famous work e.g. 'Gora', 'Chokher-Bali', 'Nauka Dubi', 'Char Ad*' fall into the category of the best Bengali novels, extremely popular and reached the masses through the,original and translated versions of his works. -

Exploitation, Victimhood, and Gendered Performance in Rituparno Ghosh’S Bariwali

EXPLOITATION, VICTIMHOOD, AND GENDERED PERFORMANCE IN RITUPARNO GHOSH’S BARIWALI Rohit K. Dasgupta and Tanmayee Banerjee Rituparno Ghosh (1961—2013) was a filmmaker, lyricist, and writer who first emerged on the cultural scene in Bengal as a copywriter at Response, a Kolkata-based advertising firm in the eighties. He made a mark for himself in the world of commercials, winning several awards for his company be- fore directing two documentaries for Doordarshan (India’s national public television). He moved into narrative film- making with the critically acclaimed Hirer Angti (Diamond Ring, 1992) and the National Award–winning Unishe April (19th April, 1995). He is credited with changing the experi- ence of cinema for the middle-class Bengali bhadrolok and 1 thus opening a new chapter in the history of Indian cinema. Ghosh arrived at a time when Bengali cinema was going Rituparno Ghosh. ©SangeetaDatta,2013 through a dark phase. Satyajit Ray had passed away in 1992 , leaving a vacuum. Although filmmakers such as Mrinal Ghosh, clearly influenced by Ray and Sen, addressed the Sen, Goutam Ghose, Aparna Sen, and Buddhadeb Dasgupta Bengali middle-class nostalgia for the past and made films “ ” contributed significantly to his genre of intellectual cinema, that were distinctly “Bengali” yet transcended its parochialism. they did not have much command over the commercial mar- Ghosh’s films were widely appreciated for their challenging “ ” ket. The contrived plots, melodrama, and obligatory fight narratives. His stories explored such transgressive social codes sequences of the action-packed Hindi cinema, so appealing to as incest in Utsab (Festival, 1999), marital rape in Dahan the masses, had barely anything intelligible to offer to those in (Crossfire, 1997), polyamory in Shubho Muharat (First Shot, search of a higher quality cinema. -

Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci

S.No. Film Name Genre Director 1 Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci . 2 The Dreamers (2003) Bernardo Bertolucci . 3 Stealing Beauty (1996) H1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 4 The Sheltering Sky (1990) I1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 5 Nine 1/2 Weeks (1986) Adrian Lyne . 6 Lolita (1997) Stanley Kubrick . 7 Eyes Wide Shut – 1999 H1.M Stanley Kubrick . 8 A Clockwork Orange [1971] Stanley Kubrick . 9 Poison Ivy (1992) Katt Shea Ruben, Andy Ruben . 1 Irréversible (2002) Gaspar Noe 0 . 1 Emmanuelle (1974) Just Jaeckin 1 . 1 Latitude Zero (2000) Toni Venturi 2 . 1 Killing Me Softly (2002) Chen Kaige 3 . 1 The Hurt Locker (2008) Kathryn Bigelow 4 . 1 Double Jeopardy (1999) H1.M Bruce Beresford 5 . 1 Blame It on Rio (1984) H1.M Stanley Donen 6 . 1 It's Complicated (2009) Nancy Meyers 7 . 1 Anna Karenina (1997) Bernard Rose Page 1 of 303 1 Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1964) Russ Meyer 9 . 2 Vixen! By Russ Meyer (1975) By Russ Meyer 0 . 2 Deep Throat (1972) Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato 1 . 2 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) Elia Kazan 2 . 2 Pandora Peaks (2001) Russ Meyer 3 . 2 The Lover (L'amant) 1992 Jean-Jacques Annaud 4 . 2 Damage (1992) Louis Malle 5 . 2 Close My Eyes (1991) Stephen Poliakoff 6 . 2 Casablanca 1942 H1.M Michael Curtiz 7 . 2 Duel in the Sun (film) (1946) I1.M King Vidor 8 . 2 The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) H1.M David Lean 9 . 3 Caligula (1979) Tinto Brass 0 . -

2019- Ftii-Srfti -Entrance Exam

Last Sample Question Paper about the Descriptive Section for JET-2019 FTII /SRFTI-ENTRANCE EXAM: Date 22nd Feb 2019. Each Question Carries 10 Marks. Sample Questions for Cinematography Course | FTII- ENTRANCE EXAM : 10. What are the various kinds of "cards" are used in DSLR cameras for recording Video Footage/ still images .What are the imp features available in such cards. 11.What is the difference between, "depth of focus" and "depth of field". 12. What is the "Lens Metadata" and what are the advantages of having it . 13. While appreciating the cinematography of any film, What are the points you would like to discuss. 14. Before starting a new shoot what kind of camera Test you would conduct to make sure that you don't face any problem while shooting. 15. Why a special Glasses are required for Watching 3-D movies. What exactly they do. 16.As a cinematographer, What are the instructions, you expect from your Director? Sample Questions for Direction and Screenplay writing Course | FTII- ENTRANCE EXAM . Q.10. Write Brief synopsis of any 2 Films among the following films released in 2018. in "two sentences or maximum 70 words. Zero: Thugs of Hindostan: Sanju: Raazi: Padmaavat: Pad Man: Mulk: Hichki: Badhaai Ho: Badhaai Ho. Q. 11.How do you Dynamise "Time and Space" in cinema. Elaborate with two examples from different European films. Q. 12. Choose one of the Following Indian films and write around 6 points why it is wonderful adaptation of short story / novel in the screenplay . 1. “ Holi” directed by Ketan Mehta 2. -

May, 2011 Subject: Monthly Media Dossier Medium Appeared In

MEDIA DOSSIER Period Covered: May, 2011 Subject: Monthly Media Dossier Medium Appeared in: Print & Online For internal circulation only Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 1 of 121 PERCEPT AND INDUSTRY NEWS Percept Limited Pg 03 ENTERTAINMENT Percept Sports and Entertainment PDM Pg 23 - Percept Activ Pg 28 - Percept ICE Pg 35 - Percept Sports _____ - Percept Entertainment _____ P9 INTEGRATED Pg 40 PERCEPT TALENT Pg 42 Content Percept Pictures Pg 43 Asset Percept IP _____ MEDIA ALLIED MEDIA Pg 46 PERCEPT OUT OF HOME Pg 50 PERCEPT KNORIGIN Pg 52 COMMUNICATIONS Advertising PERCEPT/H Pg 53 MASH _____ IBD INDIA _____ Percept Gulf _____ Hakuhodo Percept Pg 59 Public Relations PERCEPT PROFILE INDIA Pg 63 IMC PERSPECTRUM _____ INDUSTRY & COMPETITOR NEWS Pg 66 Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 2 of 121 PERCEPT LIMITED SLAMFEST Source: Experiential Marketing, Date: May, 2011 *************** Shailendra Singh, Percept Picture Company Source: Box Office India , Date: May 28. 2011 ******************** Marketing to men as potential customers! Source: Audiencematters.com; Date: May 31, 2011 Monthly Media Dossier May 2011 Page 3 of 121 Men are quite different from the females not only in their physical appearance but also when it comes to their buying habit. Marketers cannot market for men and women in the same way. It's not a simple transformation of changing colors, fonts or packaging. Men and women are different biologically, psychologically and socially. There are lots of things that marketers should keep in mind before targeting men. Men believe in purchase for ‘now’. Unlike women who don’t have anything particular in mind but still can shop for hours, men buy what they need in the recent future. -

The Changing Role of Women in Hindi Cinema

RESEARCH PAPER Social Science Volume : 4 | Issue : 7 | July 2014 | ISSN - 2249-555X The Changing Role of Women in Hindi Cinema KEYWORDS Pratima Mistry Indian society is very much obsessed with cinema. It is the and Mrs. Iyer) are no less than the revered classics of Ray or most appealing and far reaching medium. It can cut across Benegal. the class and caste boundaries and is accessible to all sec- tions of society. As an art form it embraces both elite and Women have played a number of roles in Hindi movies: the mass. It has a much wider catchment area than literature. mythical, the Sati-Savitri, the rebel, the victim and victimizer, There is no exaggeration in saying that the Indian Cinema the avant-garde and the contemporary. The new woman was has a deep impact on the changing scenario of our society in always portrayed as a rebel. There are some positive portray- such a way as no other medium could ever achieve. als of rebels in the Hindi movies like Mirch Masala, Damini, Pratighat, Zakhm, Zubeida, Mritudand and several others. Literature and cinema, the two art forms, one verbal in form The definition of an ideal Indian woman is changing in Hindi and the other visual, are not merely parallel but interactive, Cinema, and it has to change in order to suit into a changing resiprocative and interdependent. A number of literary clas- society. It has been a long hundred years since Dadasaheb sics have been made popular by the medium of cinema. Phalke had to settle for a man to play the heroine in India’s first feature film Raja Harishchandra (1913) and women in During its awesome journey of 100 years, the Indian Cinema Hindi cinema have come a long way since then. -

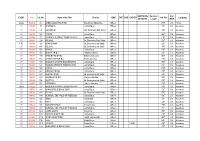

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Winner List – February 2020

3 Bill Payment Rs 250 BMS Voucher - Winner list – February 2020 FULL NAME RAJNISH KUMAR MAURYA PATTABHI SHEKAM SEKAR SURESH VSNM JAYANTI GANAPATHI SUBRAMANIAN CHANDRASEKARAN DIGAMBER PRASAD GAIROLA HEMANTH KUMAR JASMEET ARORA AZIBULLAH ANSARI PARUL SARITA KHUDA BAKHSH PATHAN ABHISHEK KOTHARI UTTAM SINGH KHUZAIMA SHABBIR HUSAIN RAMESH CHAND BAJAJ RAVINDRA C RANE PRATIK KUMAR SURESH AGRAWAL SOMNATH MUKHERJEE MANISH KUMAR SHARMA CHINTHALAPUDI HARIKRISHNA KANAKAM PRANITHA SHYAM NARAYAN YADAV ISMAIL GULAM SALEJEE JT1 MOHZAD F DUBASH JT1 SHAIKH ABDUL RAZZAQ MOHAMMAD KHALED SANTOSH VISHNU YADAV GAUTAMKUMAR VISHANJI CHHEDA KRISHNAMURTHY INGUVA KANDHAKATLA SANDHYA RATHNA G SEKAR RAMAMOHAN REDDY BHEMIREDDY PEEYUSH KHANDURIE HIRANMOY MAZUMDAR DHARAMVEER SINGH JASWANT SINGH ABHISHEK MITTAL MENDAPARA DINESHBHAI JERAMBHAI ROCHELLE ANDREA RODRIGUES HOZEFABHAI SEHRAWALA HASRATUL BEGUM SACHIN KISAN SALUNKHE DIANNE CATHERINE HOOPER SHAILENDRA SINGH NAGARJUNA N JAGPREET KAUR V GOVINDAN GOBINATH GHANSHYAM KUMAWAT PRAMOD KUMAR MOHAMMAD ZAHEER MANSOORI SAMIR KUMAR PODDAR MOHD FAZIL SATPUTE SANJAY G SHANKAR KUMAR N PRADEEP H MAHADIK RISHI GUPTA DEEPAK AHLAWAT BALASUBRAMANYA S AKSHAY AGARWAL MANSOOR KATTOOKARAN ABDUL MANAF MURUGA R FARHAD VORA JAYANT KUMAR SUDIPTA MODAK SHABD SWAROOP KHANNA IVAN PAUL HANSRAJ BRIJVALLABH MAURYA NAINAMOHAMMED S ARSHVI ARVINDBHAI DHAMECHA SOURAV KUMAR PUSHKAR JAIN KOUSHIK BANDYOPADHYAY DEEPAK DEVENDRA TUKARAM PAWAR SUNIL K MUTTA MADHURA SUNIL PANTH PATEL MANTHAN JIVAN DATTATRAY PATHAK BHAVESH SHAH SHAILENDRA KUMAR TIWARI HIRAL BHADRESH -

Critiquing Rituparna Ghosh: Gender Sensitivity and Identity in Films

Indian J. Soc. & Pol. 04(03):2017:105-108 ISSN: 2348-0084(PRINT) Special Print Issue 2017 UGC Journal List No 47956 CRITIQUING RITUPARNA GHOSH: GENDER SENSITIVITY AND IDENTITY IN FILMS MEHAK JONJUA1 1Assistant Professor, Amity University, Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar, U.P. INDIA ABSTRACT Film maker, versifier and an author, Rituparna Ghosh was Bengali and Indian cinema‟s agent provocateur and one of the most modern directors, having received both national and international acclaims for his films. He is credited for changing the Cinematic ideology, perception and impact especially for the Bengali middle class „bhadrolok‟ and moved into narrative film making with the critically acclaimed Hirer Angti in 1992 and Unishey April in 1995. Apart from projecting Bengali culture and tradition, his concepts moved around the convolutions of relationships, the niceties of feelings and the often silent hardships that are involved in everyday family life in India. His work projects the changing perceptions of the „Gender Identity‟ by dominant sensitized middle class with narratives of sexual desires, thereby demystifying existing philosophies of heteronormativity and heteropatriarchy. KEY WORDS: Films, Gender Identity and Bhadralok. INTRODUCTION period pieces, such as Antarmahal (Views of an Inner Chamber, 2005) and Chokher Bali (The Passion Play, Ghosh came into scene when Bengali Cinema 2003) Ghosh mostly restrained himself to the setting of was wheezing for breath, having been heave down over the bourgeois living room. As Sayandeb Chowdhury nearly -

Westminsterresearch the Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The Digital Turn in Indian Film Sound: Ontologies and Aesthetics Bhattacharya, I. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Indranil Bhattacharya, 2019. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] THE DIGITAL TURN IN INDIAN FILM SOUND: ONTOLOGIES AND AESTHETICS Indranil Bhattacharya A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2019 ii Abstract My project maps film sound practices in India against the backdrop of the digital turn. It is a critical-historical account of the transitional era, roughly from 1998 to 2018, and examines practices and decisions taken ‘on the ground’ by film sound recordists, editors, designers and mixers. My work explores the histories and genealogies of the transition by analysing the individual, as well as collective, aesthetic concerns of film workers migrating from the celluloid to the digital age. My inquiry aimed to explore linkages between the digital turn and shifts in production practices, notably sound recording, sound design and sound mixing. The study probes the various ways in which these shifts shaped the aesthetics, styles, genre conventions, and norms of image-sound relationships in Indian cinema in comparison with similar practices from Euro-American film industries.