Pelvic Tumors with Normal-Appearing Shapes of Ovaries and Uterus Presenting As an Emergency (Review)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Reports 95

r- CASE REPORTS 95 CASE REPORTS Past & family history were not contributory. General physical examination revealed no abnor mality. On abdominal examination- abdomen was overdistended, presenting part could not be made out, however there was suspicion of breech ABilA SINGH • NEERJA SETIII presentation. Fetal heart was not localised, mod erate uterine contractions were present. On per NEERA AGARWAL • K MISRA vaginum examination- cervix was fully effaced and 5 em dilated, soft irregular presenting part INTRODUCTION was felt high up at brim and liquor was blood 1 / Sacroccocygeal teratoma is a potentially stained. 2 2 hours later the patient delivered a 28 malignant congenital tumour. The incidence re weeks size still born female fetus weighing 850 ported in India is 1 in 30,000-40,000 live births. grns by breech. There was no PPH. Placenta These tumours present either as obstructed labour or dystocia. The case is reported because of its rare occurence. CASE REPORT Mrs. K. 22 year old unhooked, primigravida was admitted to G.T.B. Hospital with 7 months amenorrhoea and labour pains for 3 hours. Her antenatal period was uneventfull with no history of drug intake. Menstrual Cycles were regular. 'Dtpt. of 06Jt<t antf qynu, antf 'Patfw. ~cctp tttf for 'Pu6lication on 2216/ 91 fig. 1 96 JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY weighed 120 gm. There was no gmss abnormal AIIMS as she was Rb -ve. She bad a diagnostic ity detected in the placenta. laparoscopy one year back at a private hospital Examination of the fetus showed a bilobed where a bicornuate uterus was diagnosed and massofl5x 17 cmarisingfromtbesacrococcygeal excision of complete longitudinal vaginal sep region with partial rupture of one lobe, cut tum was done. -

AUC Instructions / ૂચના

AUC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, GSS, Class-1 Advertisement No. 83/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 08-07-2021 Question No. 001 – 200 (Concern Subject) Publish Date 09-07-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 16-07-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 10-07-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ૂચના Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

Statistical Analysis Plan

Cover Page for Statistical Analysis Plan Sponsor name: Novo Nordisk A/S NCT number NCT03061214 Sponsor trial ID: NN9535-4114 Official title of study: SUSTAINTM CHINA - Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Document date: 22 August 2019 Semaglutide s.c (Ozempic®) Date: 22 August 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL Clinical Trial Report Status: Final Appendix 16.1.9 16.1.9 Documentation of statistical methods List of contents Statistical analysis plan...................................................................................................................... /LQN Statistical documentation................................................................................................................... /LQN Redacted VWDWLVWLFDODQDO\VLVSODQ Includes redaction of personal identifiable information only. Statistical Analysis Plan Date: 28 May 2019 Novo Nordisk Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Version: 1.0 CONFIDENTIAL UTN:U1111-1149-0432 Status: Final EudraCT No.:NA Page: 1 of 30 Statistical Analysis Plan Trial ID: NN9535-4114 Efficacy and safety of semaglutide once-weekly versus sitagliptin once-daily as add-on to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes Author Biostatistics Semaglutide s.c. This confidential document is the property of Novo Nordisk. No unpublished information contained herein may be disclosed without prior written approval from Novo Nordisk. Access to this document must be restricted to relevant parties.This -

Ovarian Fibrothecoma - a Diagnostic Dilemma

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Ovarian fibrothecoma - a diagnostic dilemma Abstract Volume 10 Issue 3 - 2019 Background: The presentation of ovarian fibrothecoma is highly deceptive and it may Nikita Kumari,1 Bindu Bajaj2 be undiagnosed till histopathology reveals the actual diagnosis. Hence, the clinician 1 must be aware of such cases which may present as a diagnostic dilemma. Attending Consultant at Sitaram Bhartia Institute of Science and Research, Ex Senior Resident at VMMC and Safdarjung Introduction: Ovarian fibrothecomas are rare ovarian neoplasm. We report a case Hospital, India where clinical presentation was highly deceptive and suggestive of malignant tumor. 2Associate Professor at VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New However, ascitic fluid cytology revealed absent malignant cells. On histopathological Delhi, India examination, it was diagnosed as benign fibrothecoma with cystic changes. Postoperative follow-up for about six months was uneventful. Correspondence: Nikita Kumari, Attending Consultant at Sitaram Bhartia Institute of Science and Research, Ex Senior Case: A 45 year old female presented with large abdominal lump of 20 weeks size Resident at VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India, Tel associated with pain abdomen. She was admitted for management and evaluation. 9654251653, Email Hematological and biochemical parameters were normal. USG revealed a large multilocular, predominantly cystic lesion 20.9x9.6x11.4 cm in pelvis. CECT revealed Received: May 27, 2019 | Published: June 13, 2019 ovarian cystadenocarcinoma left ovary with locoregional mass effect, mild ascites and suspicious metastasis to internal iliac lymph nodes. Hence panhysterectomy and omentectomy was performed as radiological and preoperative clinical diagnosis was malignant ovarian tumor. On gross examination, a well encapsulated, multinodular cystic tumor of left ovary about 17x14x7 cm was identified. -

1 Copy Number Aberrations in Benign Serous Ovarian Tumors: a Case for Reclassification?

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 5, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2080 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Copy number aberrations in benign serous ovarian tumors: a case for reclassification? Sally M. Hunter1, Michael S. Anglesio2, Raghwa Sharma3, C. Blake Gilks2,5, Nataliya Melnyk2, Yoke-Eng Chiew4,7, Anna deFazio for the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group1, Teri A. Longacre6, Anna deFazio4,7, David G. Huntsman2,5, *Kylie L. Gorringe1, *Ian G. Campbell1. 1Centre for Cancer Genomics and Predictive Medicine, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia. 2The Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. 3Anatomical Pathology, University of Sydney and University of Western Sydney at Westmead Hospital, Australia. 4Department of Gynaecological Oncology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia. 5Genetic Pathology Evaluation Centre of the Prostate Research Centre and Department of Pathology, Vancouver General Hospital and University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, Canada. 6Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, United States. 7Westmead Institute for Cancer Research, University of Sydney at Westmead Millennium Institute, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia. *Co-senior authors Running title: Copy number aberrations in benign serous ovarian tumors Keywords: ovarian, fibroma, serous, benign, borderline. Financial support: This work was supported by a grant (ID 628630) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC). The AOCS was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under DAMD17-01-1-0729, The Cancer Council Tasmania and The Cancer Foundation of Western Australia and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC). -

Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

Review Int J Gynecol Cancer: first published as 10.1136/ijgc-2020-002018 on 7 January 2021. Downloaded from Ovarian sex cord- stromal tumors: an update INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGICAL CANCER Original research Editorials Joint statement Society statement on clinical features, molecular changes, Meeting summary Review articles Consensus statement Clinical trial Case study Video articles Educational video lecture and management Images Pathology archives Corners of the world Commentary Letters ijgc.bmj.com Rehab Al Harbi,1 Iain A McNeish,2 Mona El- Bahrawy1,3 1Department of Metabolism, ABSTRACT cord tumors with annular tubules, arise from primi- Digestion, and Reproduction, 7 Sex cord stromal- tumors are rare tumors of the ovary that tive sex cord cells. Mixed sex cord- stromal tumors Imperial College London, include Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors and sex cord- London, UK include numerous tumor subtypes of variable histological 2Department of Surgery and features and biological behavior. Surgery is the main stromal tumors that have not otherwise been spec- 7 Cancer, Imperial College therapeutic modality for the management of these ified. London, London, UK tumors, while chemotherapy and hormonal therapy may Sex cord- stromal tumors may present with an 3 Department of Pathology, be used in some patients with progressive and recurrent adnexal mass, abdominal distention, and abdom- Faculty of Medicine, University tumors. Several studies investigated molecular changes inal pain.1 Unlike epithelial and germ cell tumors, of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt in the different tumor types. Understanding molecular some sex cord- stromal tumors have clinical signs of changes underlying the development and progression of hormone production, including menstrual changes, Correspondence to sex cord-stromal tumors provides valuable information 1 Professor Mona El-Bahra wy, for diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and potential precocious puberty, hirsutism, and/or virilization. -

A Case Report of Ovarian Fibrothecoma in a Premenopausal Women with Recurrent Menorrhagia

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Jul 20; 8(C):101-105. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.4176 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: C - Case Reports Section: Case Reports in Gynecology and Obstetrics A Case Report of Ovarian Fibrothecoma in a Premenopausal Women with Recurrent Menorrhagia Meral Rexhepi1,2*, Elizabeta Trajkovska3, Hysni Ismaili2, Majlinda Azemi4 1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Clinical Hospital, Tetovo, Republic of Macedonia; 2Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Tetovo, Republic of Macedonia; 3Department of Pathology, Clinical Hospital, Tetovo, Republic of Macedonia; 4University Clinic of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, University “Ss Cyril and Methodius”, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Abstract Edited by: Igor Spiroski BACKGROUND: Ovarian fibrothecoma is a rare, benign, sex cord-stromal neoplasm, with a typically unilateral Citation: Rexhepi M, Trajkovska E, Ismaili H, Azemi M. A Case Report of Ovarian Fibrothecoma in a location in the ovary, characterized by mixed features of both fibroma and thecoma. Ovarian fibrothecoma is Premenopausal Women with Recurrent Menorrhagia. uncommon tumor of gonadal stromal cell origin accounting for 3-4% of all ovarian tumours. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Jul 20; 8(C):101-105. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.4176 CASE PRESENTATION: We presented a rare case of a 46-year-old patient with recurrent menorrhagia in the Keywords: Ovarian granulosa cell tumor; Fibrothecoma; Endometrial hyperplasia past two years with no previous medical, surgical or gynecological history. She underwent two times curettage *Correspondence: Meral Rexhepi, Department procedures. At the admission to hospital ultrasonography showed a homogenous solid right ovarian mass of size of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Clinical Hospital, 2.5 cm x 3.5 cm. -

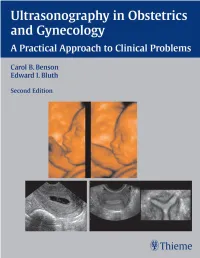

Ultrasonography in Obstetrics and Gynecology a Practical Approach to Clinical Problems Second Edition

14495FM-OBGYN.pgs.qxd 8/16/07 2:33 PM Page iii Ultrasonography in Obstetrics and Gynecology A Practical Approach to Clinical Problems Second Edition Carol B. Benson, M.D. Edward I. Bluth, M.D., F.A.C.R. Professor Chairman Emeritus Department of Radiology Department of Radiology Harvard Medical School Ochsner Health System Director of Ultrasound New Orleans, Louisiana Co-Director of High Risk Obstetrical Ultrasound Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Thieme New York • Stuttgart 14495FM-OBGYN.pgs.qxd 8/16/07 2:33 PM Page iv Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. 333 Seventh Ave. New York, NY 10001 Editor: Timothy Hiscock Editorial Assistant: David Price Vice President, Production and Electronic Publishing: Anne T. Vinnicombe Production Editor: Print Matters, Inc. Vice President, International Marketing: Cornelia Schulze Chief Financial Officer: Peter van Woerden President: Brian D. Scanlan Compositor: Compset, Inc. Printer: Everbest Printing Co. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ultrasonography in obstetrics and gynecology / [edited by] Carol B. Benson, Edward I. Bluth. — 2nd ed. p.; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-58890-612-0 (alk. paper) 1. Generative organs, Female—Ultrasonic imaging. 2. Fetus—Diseases—Diagnosis. 3. Ultrasonics in obstetrics. I. Benson, Carol B. II. Bluth, Edward I. [DNLM: 1. Genital Diseases, Female—ultrasonography. 2. Fetal Diseases—ultrasonography. 3. Pregnancy Complications—ultrasonography. 4. Ultrasonography—methods. WP 141 U462 2007] RG107.5.U4U485 2007 618’.047543—dc22 2006051488 Copyright ©2008 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. This book, including all parts thereof, is legally protected by copyright. Any use, exploitation, or commercialization outside the narrow limits set by copyright legislation without the publisher’s consent is illegal and liable to prosecution. -

Primary Ovarian Leiomyoma—A Common Tumor at an Uncommon Site

THIEME 16 Case Report Primary Ovarian Leiomyoma—A Common Tumor at an Uncommon Site Aswathy Pradeep1 Shubha Padmanabha Bhat1 Neetha Nandan1 Kishan Prasad Hosapatna Laxminarayana1 Sajitha Kaliyat1 Krishna Prasad Holalkere Venugopala1 1Department of Pathology, K S Hegde Medical Academy, Nitte Address for correspondence Shubha P. Bhat, Associate Professor, University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India Department of Pathology, K S Hegde Medical Academy, Nitte University, Karnataka 575018, India (e-mail: [email protected]). J Health Allied Sci NU 2019;1:16–20 Abstract Leiomyoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor that commonly occurs in the uterus, ovary being a rare site. Ovarian leiomyomas constitute 0.5 to 1% of all benign tumors. Keywords They probably arise from the smooth muscle cells in the ovarian hilar blood vessels. ► leiomyoma They occur most commonly in premenopausal women. We report a case of primary ► ovary ovarian leiomyoma in a 39-year-old female patient. ► smooth muscle tumor ► histopathology ► Masson’s trichrome stain Introduction of pain in the abdomen and abdominal distension since 2 months. Pain in the abdomen was in the form of dull Leiomyoms are extremely common neoplasms, overall inci- aching and intermittent type in the right lower abdomen dence being 77%. It most commonly occurs in women older with gradual abdominal distension. She also gave a his- 1 than 50 years. The most common site is the uterus. Other less tory of weight loss and irregular periods since 2 months. common sites are cervix, uterine ligaments, and ovary. Pri- Per abdomen examination, an ill-defined mass was noted mary ovarian leiomyoma is a very rare tumor and it accounts corresponding to 20 weeks in size, firm in consistency, for 0.5 to1% of all the benign ovarian neoplasms. -

Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors: an Immunohistochemical Study Including a Comparison of Calretinin and Inhibin Michael T

Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors: An Immunohistochemical Study Including a Comparison of Calretinin and Inhibin Michael T. Deavers, M.D., Anais Malpica, M.D., Jinsong Liu, M.D., Ph.D., Russell Broaddus, M.D., Ph.D., Elvio G. Silva, M.D. Department of Pathology, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas epithelial neoplasms. In addition, WT1, present in Because ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors (SCST) normal granulosa cells, is expressed by a majority of are morphologically heterogeneous neoplasms that SCSTs. Finally, these results demonstrate that cal- are relatively infrequently encountered, their diag- retinin is at least as sensitive as inhibin for ovarian nosis can be difficult. Immunohistochemical stain- SCSTs overall and that it is more sensitive than ing may be useful for establishing the diagnosis in inhibin for fibromas and FTs. problematic cases. We studied 53 ovarian SCSTs to characterize their immunohistochemical staining KEY WORDS: Calretinin, CD10, EMA, Immunohis- pattern: 17 adult granulosa cell tumors (AGCTs), 4 tochemistry, Inhibin, Keratin, Ovary, Sex cord- juvenile granulosa cell tumors (JGCTs), 3 sex cord stromal tumor, WT1. tumors with annular tubules (SCTATs), 9 Sertoli- Mod Pathol 2003;16(6):584–590 Leydig cell tumors (SLCTs), 10 fibromas, 5 fibroth- ecomas (FTs), and 5 thecomas. In 8 of the 53 cases, Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors (SCSTs) are rela- the tissue studied was from a metastatic site. The tively infrequent neoplasms that account for ap- immunopanel included calretinin, inhibin, WT1, cy- proximately 8% of all primary ovarian tumors (1). tokeratin cocktail, epithelial membrane antigen They are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms com- (EMA), and cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6). -

A Giant Extra-Uterine Fibroma Originating from an Utero-Ovarian

Marmara Medical Journal 2014; 27: 132-3 DOI: 10.5472/MMJ.2014.03084.1 CASE REPORT / OLGU SUNUMU A giant extra-uterine fibroma originating from an utero-ovarian ligament initially diagnosed as an ovarian tumour Over tümörü olarak öntanısı konulan utero-ovaryen ligamentten kaynaklanan dev ekstra-uterin fibrom Tevfik YOLDEMİR, Kemal ATASAYAN, Alper ERASLAN ABSTRACT Introduction A 44-year-old virgin with abdominal mass and anemia was admitted to our hospital. The patient complained of constipation Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle neoplasms that typically and a palpable mass in the abdomen for about 4 years. On originate from the myometrium. Their incidence among women is transabdominal ultrasonography, a giant, complex, solid, lobulated generally cited as 20-25% , but has been shown to be as high as mass 152x142x81mm in size was observed. Exploratory 70-80% in studies using histologic or sonographic examination laparotomy was performed. There was a giant, multiple lobulated [1,2]. Extra-uterine fibromas are not as common as uterine irregular-shaped solid mass occupying the whole abdomen, fibroids. They may arise in the broad ligament or at other sites reaching the xiphioid and infiltrating the omentum. The size of the where smooth muscle exists. The real incidence of extra-uterine mass arising from the left utero-ovarian ligament was approximately ligament is not well known. [3]. Among the extrauterine fibromas, 30x15cm. The histopathologic report confirmed the diagnosis of broad ligament fibroids are the most common [4] although overall leiomyoma with myxoid degeneration. incidences are rare. We present a case of a virgin who had a 30 x 15 cm fibroma arising from the left utero-ovarian ligament. -

Twisted Ovarian Fibroma, a Rare Disease

Merit Research Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences (ISSN: 2354-323X) Vol. 5(6) pp. 273-277, June, 2017 Available online http://www.meritresearchjournals.org/mms/index.htm Copyright © 2017 Merit Research Journals Case Report Twisted Ovarian Fibroma, A Rare Disease Ioannis K. Thanasas*, Tilemahos Karalis and Konstantina Balafa Abstract Department of Obstetrics – This case report is about the surgical treatment of a patient with twisted Gynecology of General Hospital in ovarian fibroma. A patient in menopausal age with a mentioned history of a Trikala, Trikala, Greece uterine fibroma came to the emergency room of our hospital with acute abdomen. Physical examination revealed the presence of a solid painful *Corresponding Author’s E-mail: pelvic mass possibly arising from the right adnexa. Imaging control [email protected] Tel.: 2431029103 / 6944766469 reinforced the diagnosis of twisted adnexal mass and a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo – oophorectomy was performed. Histological examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the ovarian fibroma. After a 5-day hospitalization and a smooth post-operative course, the patient was discharged. In this paper a literature preview of ovarian fibromas as concern as the diagnosis and the treatment methods, based on current data, is discussed. Keywords: Ovarian fibroma, twisted, diagnosis, treatment. INTRODUCTION The sex cord – gonadalstromal tumors of the ovaries 125) (Macciò et al, 2014). Ovarian fibromas occur derive from the inseparable components of the between 20 and 65 years oldwith mean ages in the fifth developing gonad and especially from the primitivesex and sixth decades (Yen et al, 2013; Taskin et al, 2014), cord or the specialized ovarian substrate.