Chapter 31 Pragmatics Yan JIANG Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incentives in China's Reformation of the Sports Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Yu Fu Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Fu, Yu, "Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1609. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1609 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Submitted to Professor Minxin Pei by Yu Fu for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract Since the 2010s, China’s sports industry has undergone comprehensive reforms. This paper attempts to understand this change of direction from the central state’s perspective. By examining the dynamics of the basketball and soccer markets, it discovers that while the deregulation of basketball is a result of persistent bottom-up effort from the private sector, the recentralization of soccer is a state-led policy change. Notwithstanding the different nature and routes between these reforms, in both sectors, the state’s aim is to restore and strengthen its legitimacy within the society. Amidst China’s economic stagnation, the regime hopes to identify sectors that can drive sustainable growth, and to make adjustments to its bureaucracy as a way to respond to the society’s mounting demand for political modernization. -

Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia Were Not the Descendants of Yan Huang

E-Leader Brno 2019 Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia were not the Descendants of Yan Huang Soleilmavis Liu, Activist Peacepink, Yantai, Shandong, China Many Chinese people claimed that they are descendants of Yan Huang, while claiming that they are descendants of Hua Xia. (Yan refers to Yan Di, Huang refers to Huang Di and Xia refers to the Xia Dynasty). Are these true or false? We will find out from Shanhaijing ’s records and modern archaeological discoveries. Abstract Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas ) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Yan Di, Huang Di, Zhuan Xu, Di Jun and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of groups, but also the names of individuals, who were regarded by many groups as common male ancestors. These groups first lived in the Pamirs Plateau, soon gathered in the north of the Tibetan Plateau and west of the Qinghai Lake and learned from each other advanced sciences and technologies, later spread out to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. The Yan Di’s offspring spread out to the west of the Taklamakan Desert;The Huang Di’s offspring spread out to the north of the Chishui River, Tianshan Mountains and further northern and northeastern areas;The Di Jun’s and Shao Hao’s offspring spread out to the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the Di Jun’s offspring lived in the west of the Shao Hao’s territories, which were near the sea or in the Shandong Peninsula.Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. -

Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results

Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results Year 10 Boys 100M Breaststroke Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 01:25.00 2 HAN HA Matthew 01:32.00 3 MING LIANG Brendan 01:33.00 4 TANG HO Yin Ting 01:54.00 5 SONG CHENG Jeremy 02:01.00 6 QING MANN Daniel 02:02.00 7 YUAN ISMAIL Amaan 02:14.00 Year 10 Boys 100M Freestyle Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 01:02.00 2 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 01:04.00 3 YUAN SIMONE Tommaso 01:06.00 4 QING DALE Rafferty 01:06.72 5 HAN XU Bruce 01:27.00 6 HAN LING Hiu Hong Felix 01:55.35 7 SONG BUDDLE Elliot 01:57.09 Year 10 Boys 50M Backstroke Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 00:36.97 2 TANG TAM Sau Ching 00:37.31 3 HAN LI Edward 00:38.37 4 MING WONG Matthew 00:40.13 5 TANG SAXENA Shaurya 00:43.37 6 SONG LACY Robert 00:49.05 7 QING GUPTA Shrey 01:27.04 Year 10 Boys 50M Butterfly Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 00:32.21 2 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 00:32.47 3 HAN LI Edward 00:34.85 4 YUAN SIMONE Tommaso 00:35.22 5 HAN DONEUX Adrien 00:36.50 6 QING KU Christopher 00:55.00 7 SONG GURNANI Vinay 01:00.95 Year 10 Boys 50M Freestyle Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 00:29.56 2 YUAN MIYAGAWA Tatsu 00:30.15 3 HAN LI Edward 00:30.28 Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results 4 TANG TAM Sau Ching 00:30.75 5 QING DALE Rafferty 00:31.19 6 TANG SAXENA Shaurya 00:32.29 7 HAN DONEUX Adrien 00:32.53 8 MING WONG Matthew 00:33.12 9 MING WONG Ernest 00:33.34 10 MING LIANG Brendan 00:33.75 11 YUAN RUDICO Francis 00:34.62 12 QING DONALD -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 8, No. 12, pp. 1698-1703, December 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0812.17 The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture Donghui Chen Henan Academy of Social Sciences, Zhengzhou, Henan, China Abstract—Huang Di culture is an important source of Chinese culture. It is not mechanical, still and solidified but melting, extensible, creative, pioneering and vigorous. It is the root of Chinese culture and a cultural system that keeps pace with the times. Its influence is enduring and universal. It has rich connotations including the “Root” Culture, the “Harmony” Culture, the “Golden Mean” Culture, the “Governance” Culture. All these have a great significance for the times and the realization of the Great Chinese Dream, therefore, it is necessary to combine the inheritance of Huang Di culture with its innovation, constantly absorb the fresh blood of the times with a confident, open and creative attitude, give Huang Di culture a rich connotation of the times, tap the factors in Huang Di culture that fit the development of the modern times to advance the progress of the country and society, and make Huang Di culture still full of vitality in the contemporary era. Index Terms—Huang Di, Huang Di culture, Chinese culture I. INTRODUCTION Huang Di, being considered the ancestor of all Han Chinese in Chinese mythology, is a legendary emperor and cultural hero. His victory in the war against Emperor Chi You is viewed as the establishment of the Han Chinese nationality. He has made great many accomplishments in agriculture, medicine, arithmetic, calendar, Chinese characters and arts, among which, his invention of the principles of Traditional Chinese medicine, Huang Di Nei Jing, has been seen as one of the greatest contributions to Chinese medicine. -

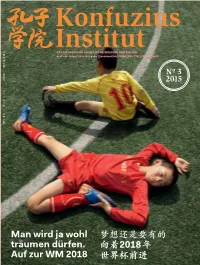

Man Wird Ja Wohl Träumen Dürfen. Auf Zur WM 2018 梦想还是要有的向着

Konfuzius 中 Institut DAS MAGAZIN FÜR CHINESISCHE SPRACHE UND KULTUR 德 文 deutsch-chinesische Ausgabe | zweimonatlich | ISSN: 2095-7742 | CN10-1188/C 对 照 版 ● 双 Nº– 3 月 刊 2015 ● 2 0 1 5 年 5 月 ● 总 第 8 期 企 足 而 待 qǐ zú ér dài hoffnungsvoll erwarten; wörtlich: auf den Zehen- spitzen stehend etwas erwarten Man wird ja wohl 梦想还是要有的 träumen dürfen. 向着2018年 Auf zur WM 2018 世界杯前进 Editorial CONFUCIUS INSTITUTE 国国家领导人习近平是位热情的足 hinas Staatschef Xi Jinping ist ein begeisterter Fußballfan. »Kon球迷,这从各方面来讲真是个幸fuzius Institut«-MagaDaszi istn ine vielerlei in m Hinsichtehr eine rGlücksfall.en S Alspr Parteivorsitachen- C zender hat er den Aufschwung des Fußballs sogar in dem 中 事。作为党的总书记,他将振兴足 von ihm propagierten »Chinesischen Traum« festgeschrieben und 球纳入到由其倡导的“中国梦”,并且迅即列 ab sofort zur Chefsache erklärt. Obwohl bereits in vielen Sportarten 为重大事务。尽管中国在众多体育项目奖牌 ein hoher Medaillenspiegel erzielt wird, spielt der Profifußball bis- Jederzeit uhern kaumd üeineb Rollee inr China.all Die d chinesischeabe Nationalmannschafti 榜上高居前列,但迄今为止中国职业足球却是 rangiert lediglich auf Platz 77 der Weltrangliste. Völlig inakzepta- 乏善可陈。中国国家足球队的世界排名只不 bel findet das die chinesische Staatsführung und überträgt kurzer- 过位列第 77名,这在中国政府看来完全不可 hand die Nachwuchsförderung vom Nationalverband auf das Er- 接受,故而果断地将足球人才培养从中国足 ziehungsministerium. Mit neuen Strukturen und Methoden soll die 球协会转交给教育部。借助新的体制和方法, Förderung des Fußballs im Reich der Mitte vorangetrieben werden. Landesweit wird der Fußball an immer mehr Schulen in den Unter- 有望推动中国足球的发展。足球在全国越来 richtsplan aufgenommen und ist für Millionen von Kindern Pflicht- 越多的学校被纳入到了教学计划,并且 fach. Für Xi Jinping ist es lediglich eine Frage der Zeit, bis Chinas 成为了上百万儿童的必修课程。在习近平看 Nationalelf den Sprung an die Weltspitze schafft. Konfuzius Institut 来,中国国家队跃居世界顶尖球队只不过是 Und wer hat den Fußball erfunden? Folgen Sie uns in einer sportlichen Zeitreise zu den Anfängen des Fußballspiels in China 个时间问题。 bis zum heutigen Engagement der chinesischen Millionäre, den 到底是谁发明了足球?请您跟随我们做 heimischen Fußball auf Weltniveau zu trimmen. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT About IHV The Institute of Human Virology (IHV) is the first center in the United States—perhaps the world— to combine the disciplines of basic science, epidemiology and clinical research in a concerted effort to speed the discovery of diagnostics and therapeutics for a wide variety of chronic and deadly viral and immune disorders—most notably HIV, the cause of AIDS. Formed in 1996 as a partnership between the State of Maryland, the City of Baltimore, the University System of Maryland and the University of Maryland Medical System, IHV is an institute of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and is home to some of the most globally-recognized and world- renowned experts in the field of human virology. IHV was co-founded by Robert Gallo, MD, director of the of the IHV, William Blattner, MD, retired since 2016 and formerly associate director of the IHV and director of IHV’s Division of Epidemiology and Prevention and Robert Redfield, MD, resigned in March 2018 to become director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and formerly associate director of the IHV and director of IHV’s Division of Clinical Care and Research. In addition to the two Divisions mentioned, IHV is also comprised of the Infectious Agents and Cancer Division, Vaccine Research Division, Immunotherapy Division, a Center for International Health, Education & Biosecurity, and four Scientific Core Facilities. The Institute, with its various laboratory and patient care facilities, is uniquely housed in a 250,000-square-foot building located in the center of Baltimore and our nation’s HIV/AIDS pandemic. -

Women Lai Jiang Zhongwen! Æ‹‚Ä»¬Æš¥È®²Ä¸Łæœ

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Geneseo Authors Milne Library Publishing 1-1-2013 WOMEN LAI JIANG ZHONGWEN! 我们来 讲中文!Let’s Speak Chinese! Jasmine Kong-Yan Tang SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/geneseo-authors Recommended Citation Tang, Jasmine Kong-Yan, "WOMEN LAI JIANG ZHONGWEN! 我们来讲中文!Let’s Speak Chinese!" (2013). Geneseo Authors. 7. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/geneseo-authors/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Milne Library Publishing at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geneseo Authors by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOMEN LAI JIANG ZHONGWEN! 我们来讲中文! Authors LET’S SPEAK CHINESE! 李公燕 by JASMINE KONG-YAN TANG WOMEN LAI JIANG ZHONGWEN! 我们来讲中文! LET’S SPEAK CHINESE! 李公燕 By JASMINE KONG-YAN TANG ©2013 Jasmine Kong-Yan Tang Published by Milne Library, State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 Cover photographs by Jasmine Kong-Yan Tang Cover and book design by Allison P. Brown Sound recordings produced by Steve Dresbach, read by Jasmine Kong-Yan Tang and Steve Dresbach. About this Textbook This book is for those with experience learning Mandarin but who need confidence interacting in everyday situations. What distinguishes Let’s Speak Chinese! from other language acquisition guides is the emphasis on practical usage and the promotion of self-learning. To speak the language with ease, one needs to find the courage to simply ask for what you want in order to receive what you seek. Once you are able to do so, then vocabulary, grammar rules, and intonation will flow more smoothly in your speech. -

East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (EASTM - Universität Tübingen)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (EASTM - Universität Tübingen) EASTM 42 (2015): 39-71 The Experience of Illness in Early Twentieth-century Rural Shanxi Henrietta Harrison [Henrietta Harrison is professor of modern Chinese studies at Oxford University. She received her doctorate from Oxford University in 1996 and subsequently taught at Leeds and Harvard universities. She works mainly on the history of central Shanxi and has published a biography of Liu Dapeng (The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village 1857- 1942, 2005) as well as a history of a Catholic village in the same area (The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village, 2013). Contact: [email protected]] * * * Abstract: This paper uses the diary and other records of Liu Dapeng 劉大鵬 (1857-1942), a Shanxi village resident, to examine how people in rural China experienced and understood illness at an important time of transition for medical systems in China. It explains how Liu understood the illnesses that afflicted himself and members of his family in terms of providence. The healing methods he used ranged through self-medication with folk remedies and modern patent medicines; remedies provided by families friends and neighbours (including acupuncture and prescriptions based on classical Chinese medicine); remedies provided by gods and shamans; and prescriptions provided by professional doctors of Chinese medicine, whom Liu deeply distrusted. It also examines the arrival of Western medicine in Shanxi and argues that while this existed it was incorporated into networks of medicine provided by family and friends, rather than functioning as a separate institutional system. -

Using Online Applications to Improve Tone Perception Among L2 Learners of Chinese (网络应用对中文二语学习者声调辨识的有效性研究)

Journal of Technology and Chinese Language Teaching Volume 10 Number 1, June 2019 http://www.tclt.us/journal/2019v10n1/xulili.pdf pp. 26-56 Using Online Applications to Improve Tone Perception among L2 Learners of Chinese (网络应用对中文二语学习者声调辨识的有效性研究) Xu, Hongying Li, Yan Li, Yingjie (徐红英) (李艳) (李颖颉) University of University of University of Colorado- Wisconsin-La Crosse Kansas Boulder (威斯康星大学拉克 (堪萨斯大学) (科罗拉多大学博尔得分 罗校区) [email protected] 校) [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: This study investigated the effectiveness of an online application in helping beginning-level Chinese learners improve their perception of the tones in Mandarin Chinese. Two groups—one experimental and one traditional—of beginning Chinese learners from two universities in the Midwest participated in this study. The experimental group (n=20) used the online application to practice tones for four 15-minute sessions in class. The traditional group (n=11) participated in traditional instructor-led practice in class in lieu of the online practice. Both groups completed a pre-test, an immediately administered post-test, and a delayed post-test designed to assess their perception of the tones of monosyllabic and disyllabic words. No statistically significant difference has been found between the two groups in their tone perception performance in the post-test and in the delayed post-test. However, the experimental group showed a positive trend in improving their perception on those tones which posed more difficulty than others. Their experience with this online application and the pronunciation learning strategies of participants in the experimental group were also examined through a survey. Based on the findings, it is proposed that the use of online tone practice is worthwhile in a Chinese language class, but might fit better into the curriculum as external assignments. -

The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development

THE SAXOPHONE IN CHINA: HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT Jason Pockrus Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Eric M. Nestler, Major Professor Catherine Ragland, Committee Member John C. Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pockrus, Jason. The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 222 pp., 12 figures, 1 appendix, bibliography, 419 titles. The purpose of this document is to chronicle and describe the historical developments of saxophone performance in mainland China. Arguing against other published research, this document presents proof of the uninterrupted, large-scale use of the saxophone from its first introduction into Shanghai’s nineteenth century amateur musical societies, continuously through to present day. In order to better describe the performance scene for saxophonists in China, each chapter presents historical and political context. Also described in this document is the changing importance of the saxophone in China’s musical development and musical culture since its introduction in the nineteenth century. The nature of the saxophone as a symbol of modernity, western ideologies, political duality, progress, and freedom and the effects of those realities in the lives of musicians and audiences in China are briefly discussed in each chapter. These topics are included to contribute to a better, more thorough understanding of the performance history of saxophonists, both native and foreign, in China.