Harvey Glatman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serial Killers

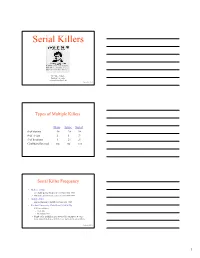

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

Richard Cottingham”

Serial Killer “ Richard Cottingham” by Sekton Wandikbo This is a story about a serial killer and rapist that operated in New York and New Jersey. His name is Richard Francis Cottingham. He was born in “ Bronx, New York on November 25, 1946. He grew up in a normal middle-class home. When he was 12-year-old, his parents moved the family to River Vale, New Jersey. There his father worked in an insurance company and his mother stayed home.” 1 He was an aloof person when he was a teenager, he did not have a lot of friends to play with neither in his neighborhood nor at school. After graduating from St.Andrews high school, he worked as a computer operator at his father’s insurance company for two years. After that he moved to another insurance company called Blue Cross Blue Shield, working the same job. He has a wife with three children. He started killing in 1967 and stopped in 1980. He was sentenced to jail for life. Cottingham is found guilty for killing "six victims."2 The first killing-spree began “ in 1967, when he was 21-year-old. He strangled his friend, a 29-year-old Nancy Vogel to death. Her body was found in her car in nearby Ridgefield Park. She had been last seen three days earlier, when she left home to play bingo with friends at a local church.” 3 He committed this murder 1 Charles Montaldo, “ Profile of Serial Killer Richard Cottingham” ThoughtCo, March 04, 2017. https://www.thoughtco.com/profile-of-serial-killer-richard-cottingham-973146 2 Jacklyn Cowin, Jenna Leonette, and The Phan, " Richard Francis Cottingham " The Torso Killer", " PDF, 2007. -

Richard Francis Cottingham “The Torso Killer”

Richard Francis Cottingham “The Torso Killer” Information researched and summarized by Jacklyn Cowin, Jenna Leonette, and The Phan Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Age Life Event 11/25/1946 0 Born in Bronx, NY 1958 12 Family settled in River Vale, NJ when Richard was still a youngster Entered in the seventh grade at St. Andrews, a parochial school for boys and 1958 12 girls—had trouble making friends, took an interest in homing pigeons and tinkering around the house and yard with his mother Entered Pascack Valley High School in Hillsdale-became more accepted by 1960 14 peers, but he was never a star, he just blended in with the crowd. Joined cross country and track team—he picked the event that suited his 1960-1964 14-18 personality; he chose the solitude and loneliness of the long distance runner. 1964 18 Graduated from Pascack Valley High School Worked for father’s insurance company Metropolitan Life as a computer operator 1964-1966 18-20 and took courses to learn more about computers. 1966 20 Joined Blue Cross Blue Shield of Greater New York as a computer operator 1967 21 Strangled to death Nancy Schiava Vogel (WF, 29) Charged and convicted of intoxicated driving (New York City): 10 days jail & 10/03/1969 22 $50 fine 05/03/1970 23 Married Janet at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Queens Village, NY Lived at the apartments called Ledgewood Terrace in Little Ferry, the site where 1970-1974 23-28 his first victim Maryann Carr, was later found dead. -

David A. Sklansky Traffic Stops, Minority Motorists

DAVID A. SKLANSKY TRAFFIC STOPS, MINORITY MOTORISTS, AND THE FUTURE OF THE FOURTH AMENDMENT Most Americans never have been arrested or had their homes searched by the police, but almost everyone has been pulled over. Traffic enforcement is so common it can seem humdrum. Not- withstanding the occasional murder suspect caught following a for- tuitous vehicle code violation,' even the police tend to view traffic enforcement as "peripheral to 'crime fighting.'"2 Fourth Amendment decisions about traffic enforcement can seem peripheral, too. Every criminal lawyer knows that the Su- preme Court treats the highway as a special case. Motorists receive reduced protection against searches and seizures, in part because David A. Sklansky is Acting Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law. AuTHOR'S NoTE: I received helpful criticism from Peter Arenella, Ann Carlson, Steven Clymer, Robert Goldstein, Pamela Karlan, Deborah Lambe, Jeff Sklansky, Carol Steiker, William Stuntz, and Eugene Volokh, financial support from the UCLA Chancellor's Office, and research assistance from the Hugh & Hazel Darling Law Library. ' See, for example, Stephen Braun, Trooper's Vigilance Led to Arrest of Blast Suspect, LA Times Al (Apr 22, 1995) (describing arrest of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh following traffic stop); Richard Simon, Traffic Stops-Tickets to Sinprises, LA Times BI (May 15, 1995) (noting that serial killers Ted Bundy and Randy Kraft were caught during traffic stops). 2 David H. Bayley, Policefor the Future 29 (Oxford, 1994). Not surprisingly, traffic officers take a different view. See id; Simon, Traffic Stops, LA Times at BI (quoting California Highway Patrol Sgt. Mike Teixiera's assertion that "[w]e probably get more murderers stopping them for speeding than we do by looking for them"). -

WRIT NO. L-77-L79-A 114TH JUDICIAL COURT

WRIT NO. l-77-l79-A TRIAL COURT NO, 1-7’7—179 EX PARTE § IN THE DISTRICT COQV «[3: § § 114TH JUDICIAL COURT . § KERRY MAX COOK § SMITH COUNTY, TEXAS ADDITIONAL EXHIBITIN SUBPORTjDF APPLICATION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT: NOW COMES the Applicant, KERRY MAX COOK, and submits the following additional exhibits in support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus: 1,, Affidavit from Gregg O. McCrary. Respectfully submitted, GARY A. UDASHEN Bar Card No. 20369590 BRUCE ANTON Bar Card No. 01274700 SORRELS, UDASHEN & ANTON 2311 Cedar Springs Road, Suite 250 Dallas, TeXas 75201 214-468-8100 214-468-8104 fax www.sualaw.com gau@s_ualaw.com For The Innocence Project of Texas -and- - Additional Exhibit in Support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus Page 1 NINA MORRISON BARRY SCHECK INNOCENCE PROJECT, INC. 40 Worth Street, Suite 701 New York, New YOrk 10013 214-364-5340 214-364-5341 (Fax) Of Counsel Attorneys for Kerry Max Cook CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE The undersigned hereby certifies that a true and Correct copy of the foregoing Applicant’s Additional Exhibits In Support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus Was mailed to the following individuals, on this the 27th day of May, 2016: D. Matt Bingham Criminal District Attorney 100 N. Broadway, 4th Floor Tyler, Texas 75702 Michael J. West Assistant Criminal District Attorney 100 N-. Broadway, 4th Floor Tyler, Texas 75702 ’ Keith Dollahite Special Prosecutor 5457' Donnybrook Avenue Tyler, Texas 75703 Allen Gardner Special Prosecutor 102 N. College, Suite 800 Tyler, TeXas 75702 4" GARY A. -

USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis…

5/4/2010 USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis… H-1B Approved Petitioners Fiscal Year 2009 The file below is a list of petitioners who received an approval in fiscal year 2009 (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) of Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, requesting initial H- 1B status for the beneficiary, regardless of when the petition was filed with USCIS. Please note that approximately 3,000 initial H- 1B petitions are not accounted for on this list due to missing petitioner tax ID numbers. Related Files H-1B Approved Petitioners FY 2009 (1KB CSV) Last updated:01/22/2010 AILA InfoNet Doc. No. 10042060. (Posted 04/20/10) uscis.gov/…/menuitem.5af9bb95919f3… 1/1 5/4/2010 http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resource… NUMBER OF H-1B PETITIONS APPROVED BY USCIS IN FY 2009 FOR INITIAL BENEFICIARIES, EMPLOYER,INITIAL BENEFICIARIES WIPRO LIMITED,"1,964" MICROSOFT CORP,"1,318" INTEL CORP,723 IBM INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED,695 PATNI AMERICAS INC,609 LARSEN & TOUBRO INFOTECH LIMITED,602 ERNST & YOUNG LLP,481 INFOSYS TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED,440 UST GLOBAL INC,344 DELOITTE CONSULTING LLP,328 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED,320 CISCO SYSTEMS INC,308 ACCENTURE TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS,287 KPMG LLP,287 ORACLE USA INC,272 POLARIS SOFTWARE LAB INDIA LTD,254 RITE AID CORPORATION,240 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO,236 DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP,235 COGNIZANT TECH SOLUTIONS US CORP,233 MPHASIS CORPORATION,229 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LIMITED,219 BLOOMBERG,217 MOTOROLA INC,213 GOOGLE INC,211 BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCH SYSTEM,187 UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND,185 UNIV OF MICHIGAN,183 YAHOO INC,183 -

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES of WRONGDOING in FILM and LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Norther

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES OF WRONGDOING IN FILM AND LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Scott Balcerzak, Director This dissertation examines true crime’s ubiquitous influence on literature, film, and culture. It dissects how true-crime narratives affect crime fiction and film, questioning how America’s continual obsession with crime underscores the interplay between true crime narratives and their fictional equivalents. Throughout the 20th century, these stories represent key political and social undercurrents such as movements in religious conservatism, issues of ethnic and racial identity, and developing discourses of psychology. While generally underexplored in discussions of true crime and crime fiction, these currents show consistent shifts from a liberal rehabilitative to a conservative punitive form of crime prevention and provide a new way to consider these undercurrents as culturally-engaged genre directives. I track these histories through representative, seminal texts, such as Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1925), W.R. Burnett’s Little Caesar (1929, Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952), and Barry Michael Cooper’s 1980s new journalism pieces on the crack epidemic and early hip hop for the Village Voice, examining how basic crime narratives develop through cultural changes. In turn, this dissertation examines film adaptations of these narratives as well, including George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun (1951), Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar (1972), Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me (2010), and Mario Van Peeble’s New Jack City (1991), accounting for how the medium changes the crime narrative. In doing so, I examine true crime’s enduring resonance on crime narratives by charting the influence of commonly overlooked early narratives, such as execution sermons and murder ballads. -

Serial Killers

Abdallah al-Hubal Name(s): al-Hubal, Abdallah Alias: Official bodycount: 13 Location: Yemen Claimed bodycount: 13 Abel Latif Sharif Name(s): Sharif, Abel Latif Alias: El Depredador Psicópata Official bodycount: 1 Location: Mexico and USA Claimed bodycount: 17 Ahmad Suradji Name(s): Suradji, Ahmad Alias: Official bodycount: 42 Location: Indonesia Claimed bodycount: 42 Aileen Wuornos Name(s): Wuornos, Aileen Alias: Official bodycount: 7 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 7 Albert DeSalvo Name(s): DeSalvo, Albert Alias: Boston Strangler, the Official bodycount: 13 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 13 Albert Fish Name(s): Fish, Albert Alias: Gray Man, the Official bodycount: 15 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 15 Ali Reza Khoshruy Kuran Kordiyeh Name(s): Kordiyeh, Ali Reza Khoshruy Kuran Alias: Teheran Vampire, the Official bodycount: 9 Location: Iran Claimed bodycount: 9+ Alton Coleman & Debra Brown Name(s): Coleman, Alton + Brown, Debra Alias: Official bodycount: 8 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 8 Anatoly Golovkin Name(s): Golovkin, Anatoly Alias: Official bodycount: 11 Location: Russia Claimed bodycount: 11 Anatoly Onoprienko Name(s): Onoprienko, Anatoly Alias: Terminator, the Official bodycount: 52 Location: Ukraine Claimed bodycount: 52 Andonis Daglis Name(s): Daglis, Andonis Alias: Athens Ripper, the Official bodycount: 3 Location: Greece Claimed bodycount: 3 Andras Pandy Name(s): Pandy, Andras Alias: Official bodycount: 6 Location: Belgium Claimed bodycount: 60+ André Luiz Cassimiro Name(s): Cassimiro, André Luiz Alias: Official bodycount: -

1St Quarter 1999 Jobs • Meetings • Courses

RONNICHOLS The President's Desk OOnce again, I find myself having the dis- The very rough plan is to have this pro- tinct pleasure to write this quarter’s address. gram channeled through the regional direc- By now I am certain that you are quite uncer- tors to the study group chairs within each tain as to what to expect. “Is Ron going to phi- region. Each study group will then be respon- losophize or is Ron going to empty his spleen?” sible for maintaining the mentoring program “Or, if he has nothing intelligent to say, will he within their specialty. Once established, long at least be entertaining?!” Read on and see. distance mentoring programs will be ex- Knowing firsthand that a successful semi- plored for out-of-state members. As I indi- nar is the result of teamwork, I wish to person- cated, this is a very rough plan. But the first ally extend a warm thank you to the staff of the hurdle has been cleared. Your laboratory di- San Diego Police Dept. Crime Lab for a job that rectors and supervisors have stepped up to was well done. The location, the accommoda- the plate and said they will support and cover tions, the amenities, the program, the food and such a program. the hospitality were all fantastic. The seminar Now it’s your turn. This association has program received high marks with workshops nearly 500 members. Some of them, being and presentations that were informative and laboratory directors and supervisors have al- applicable. We were even treated with a National League Champion- ready pledged their support. -

Fatal Attraction : the Serial Killer in American Popular Culture Bentham, AA

Fatal attraction : the serial killer in American popular culture Bentham, AA Title Fatal attraction : the serial killer in American popular culture Authors Bentham, AA Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/57498/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Fatal Attraction: The Serial Killer in American Popular Culture If a single figure can be said to exemplify American popular culture’s apparent fascination with violence, it is the enigmatic serial murderer. The mythos that has sprung up around the serial killer is both potent and ubiquitous; representations occur in various forms of media, including fiction, true crime, film and television, music, and graphic novels. So iconic is this figure, that one can even purchase serial killer action figures, trading cards and murderabilia.1 Notably, this is not an entirely niche market; CDs of Charles Manson’s music can be purchased from Barnes & Noble and, in 2010, Dexter action figures were available to purchase in Toys R Us. Indeed, the polysemic serial killer holds such a unique place in the cultural imaginary that he or she has in some ways come to be seen as emblematic of America itself. -

Sadomasochism

Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 2 March 2018 Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014 Robert Peters Morality in Media & National Center on Sexual Exploitation, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Clinical Psychology Commons, Community- Based Research Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Peters, Robert (2018) "Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014," Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.23860/dignity.2018.03.02.02 Available at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol3/iss2/2https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol3/iss2/2 This Resource is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dignity: A Journal on Sexual Exploitation and Violence by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sadomasochism: Descent into Darkness, Annotated Accounts of Cases, 1996-2014 Abstract A collection of accounts of sadomasochistic sexual abuse from news reports and scholarly and professional sources about the dark underbelly of sadomasochism and the pornography that contributes to it. It focuses on crimes and other harmful sexual behavior related to the pursuit of sadistic sexual pleasure in North America and the U.K. -

The Incidence of Child Abuse in Serial Killers

Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 2005, Volume 20, Number 1 The Incidence of Child Abuse in Serial Killers Heather Mitchell and Michael G. Aamodt Radford University Fifty serial killers who murdered for the primary goal of attaining sexual gratification, termed lust killers, were studied to determine the prevalence of childhood abuse. Informa- tion regarding the childhood abuse sustained by each killer was obtained primarily from biographical books, newspaper articles, and online sites. Abuse was categorized into physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and neglect and was then compared to societal norms from 2001. Abuse of all types excluding neglect was significantly higher in the serial killer population. For serial killers, the prevalence of physical abuse was 36%; sexual abuse was 26%; and psychological abuse was 50%. Neglect was equally prevalent in the serial killer (18%) and societal norm populations. SERIAL KILLER is defined as a injury involving brain damage, brain person who murders three or anomalies, and faulty genetics. Familial A more persons in at least three contributions include the physical ab- separate events, with a “cooling off pe- sence or lack of personal involvement by riod” between kills (Egger, 2002; one or both parents and alcohol or drug Hickey, 2002; Ressler & Shachtman, dependency by one or both parents. 1992). Serial killers have a type of cycle Perhaps one of the most interesting fac- during which they kill, presumably dur- tors contributing to the development of a ing some period of stress. After the ca- serial killer is abuse that is experienced thartic experience is accomplished, they in the killer’s childhood.