Jerry Buting Are Trying to Change the System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habeas Corpus: the Wrongful Imprisonment of Steven Avery

Peer Reviewed Proceedings of the 7th Annual Conference Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand (PopCAANZ), Sydney, 29 June–1 July, 2016, pp. 11-20. ISBN: 978-0-473-38284-1. © 2016 RACHEL FRANKS State Library of New South Wales; The University of Sydney KIM D. WEINERT Bond University Habeas Corpus: the wrongful imprisonment of Steven Avery ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The politics of the body have been debated at length; ideas of moral and Steven Avery natural rights to protect individual autonomy have been presented in the Habeas context of class, gender and race for centuries. Such sovereignty has been Corpus entrenched in law through the recourse of habeas corpus: the right of Imprisonment redress for unlawful detention or imprisonment before a court. This paper Making a looks at habeas corpus through the lens of the recent ten-part documentary, Murderer Making a Murderer (2015), created by Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, Social media and streamed on Netflix. This web-television series unpacks the wrongful Television imprisonment of Steven A. Avery (who served eighteen years for rape), and posits the recent imprisonments of Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey, both serving life sentences for murder, are also wrongful. This paper also provides a brief overview of the history of the writ of habeas corpus and offers an outline for the continuing importance – within the justice system and within popular culture – of this legal right. INTRODUCTION The politics of the body have been debated at great length; lawyers, philosophers, politicians and sociologists often jostling for position around ideas of moral and natural rights to protect individual autonomy. -

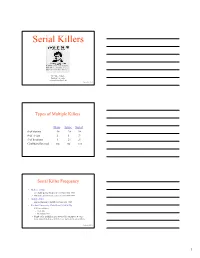

Serial Killers

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

Maclauchlin, Scott a - DOC

MacLauchlin, Scott A - DOC From: Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 9:14 AM To: Meisner, Michael F - DOC; Tarr, David R - DOC Subject: RE: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Should mailroom be pulling any information that comes in from IWW addressed to inmates? From: Meisner, Michael F - DOC Sent: Monday, August 22, 2016 7:42 AM To: Tarr, David R - DOC; Hautamaki, Sandra J - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Schwochert, James R - DOC Sent: Sunday, August 21, 2016 6:59 PM To: DOC DL DAI Wardens CO Dir Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI From: Jess, Cathy A - DOC Sent: Friday, August 19, 2016 3:04 PM To: Schwochert, James R - DOC; Weisgerber, Mark L - DOC Cc: Hove, Stephanie R - DOC; Clements, Marc W - DOC Subject: FW: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana FYI Indiana information on September 9 possible work stoppage of inmates. From: Basinger, James [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, August 18, 2016 7:44 PM To: Joseph Tony Stines Subject: SEP 9 work stoppage Indiana Just an FYI on Intel we got today. I would check your systems and databases for Randall Paul Mayhugh, of Terre Haute, IN. Mr. Mayhugh poses as a Union member for a group that call themselves Industrial Workers of the world (IWW). Let know if you find anything. Be safe ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Looks like Leonard McQuay and one of his outside associates are attempting to facilitate involve my in this movement. I know offender McQuay quite well and it doesn't surprise me that we would try to initiate this type of action. -

David A. Sklansky Traffic Stops, Minority Motorists

DAVID A. SKLANSKY TRAFFIC STOPS, MINORITY MOTORISTS, AND THE FUTURE OF THE FOURTH AMENDMENT Most Americans never have been arrested or had their homes searched by the police, but almost everyone has been pulled over. Traffic enforcement is so common it can seem humdrum. Not- withstanding the occasional murder suspect caught following a for- tuitous vehicle code violation,' even the police tend to view traffic enforcement as "peripheral to 'crime fighting.'"2 Fourth Amendment decisions about traffic enforcement can seem peripheral, too. Every criminal lawyer knows that the Su- preme Court treats the highway as a special case. Motorists receive reduced protection against searches and seizures, in part because David A. Sklansky is Acting Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law. AuTHOR'S NoTE: I received helpful criticism from Peter Arenella, Ann Carlson, Steven Clymer, Robert Goldstein, Pamela Karlan, Deborah Lambe, Jeff Sklansky, Carol Steiker, William Stuntz, and Eugene Volokh, financial support from the UCLA Chancellor's Office, and research assistance from the Hugh & Hazel Darling Law Library. ' See, for example, Stephen Braun, Trooper's Vigilance Led to Arrest of Blast Suspect, LA Times Al (Apr 22, 1995) (describing arrest of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh following traffic stop); Richard Simon, Traffic Stops-Tickets to Sinprises, LA Times BI (May 15, 1995) (noting that serial killers Ted Bundy and Randy Kraft were caught during traffic stops). 2 David H. Bayley, Policefor the Future 29 (Oxford, 1994). Not surprisingly, traffic officers take a different view. See id; Simon, Traffic Stops, LA Times at BI (quoting California Highway Patrol Sgt. Mike Teixiera's assertion that "[w]e probably get more murderers stopping them for speeding than we do by looking for them"). -

WRIT NO. L-77-L79-A 114TH JUDICIAL COURT

WRIT NO. l-77-l79-A TRIAL COURT NO, 1-7’7—179 EX PARTE § IN THE DISTRICT COQV «[3: § § 114TH JUDICIAL COURT . § KERRY MAX COOK § SMITH COUNTY, TEXAS ADDITIONAL EXHIBITIN SUBPORTjDF APPLICATION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT: NOW COMES the Applicant, KERRY MAX COOK, and submits the following additional exhibits in support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus: 1,, Affidavit from Gregg O. McCrary. Respectfully submitted, GARY A. UDASHEN Bar Card No. 20369590 BRUCE ANTON Bar Card No. 01274700 SORRELS, UDASHEN & ANTON 2311 Cedar Springs Road, Suite 250 Dallas, TeXas 75201 214-468-8100 214-468-8104 fax www.sualaw.com gau@s_ualaw.com For The Innocence Project of Texas -and- - Additional Exhibit in Support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus Page 1 NINA MORRISON BARRY SCHECK INNOCENCE PROJECT, INC. 40 Worth Street, Suite 701 New York, New YOrk 10013 214-364-5340 214-364-5341 (Fax) Of Counsel Attorneys for Kerry Max Cook CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE The undersigned hereby certifies that a true and Correct copy of the foregoing Applicant’s Additional Exhibits In Support of Application for Writ of Habeas Corpus Was mailed to the following individuals, on this the 27th day of May, 2016: D. Matt Bingham Criminal District Attorney 100 N. Broadway, 4th Floor Tyler, Texas 75702 Michael J. West Assistant Criminal District Attorney 100 N-. Broadway, 4th Floor Tyler, Texas 75702 ’ Keith Dollahite Special Prosecutor 5457' Donnybrook Avenue Tyler, Texas 75703 Allen Gardner Special Prosecutor 102 N. College, Suite 800 Tyler, TeXas 75702 4" GARY A. -

How “Making a Murderer” Went Wrong

Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter A Critic at Large JANUARY 25, 2016 ISSUE Dead Certainty How “Making a Murderer” goes wrong. BY KATHRYN SCHULZ A private investigative project, bound by no rules of procedure, is answerable only to ratings and the ethics of its makers. ILLUSTRATION BY SIMON PRADES rgosy began in 1882 as a magazine for children and ceased publication ninety-six years later as Asoft-core porn for men, but for ten years in between it was the home of a true-crime column by Erle Stanley Gardner, the man who gave the world Perry Mason. In eighty-two novels, six films, and nearly three hundred television episodes, Mason, a criminal-defense lawyer, took on seemingly guilty clients and proved their innocence. In the magazine, Gardner, who had practiced law before turning to writing, attempted to do something similar—except that there his “clients” were real people, already convicted and behind bars. All of them met the same criteria: they were impoverished, they insisted that they were blameless, they were serving life sentences for serious crimes, and they had exhausted their legal options. Gardner called his column “The Court of Last Resort.” To help investigate his cases, Gardner assembled a committee of crime experts, including a private detective, a handwriting analyst, a former prison warden, and a homicide specialist with degrees in both medicine and law. They examined dozens of cases between September of 1948 and October of 1958, ranging from an African-American sentenced to die for killing a Virginia police officer after a car chase—even though he didn’t know how to drive—to a nine-fingered convict serving time for the strangling death of a victim whose neck bore ten finger marks. -

USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis…

5/4/2010 USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis… H-1B Approved Petitioners Fiscal Year 2009 The file below is a list of petitioners who received an approval in fiscal year 2009 (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) of Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, requesting initial H- 1B status for the beneficiary, regardless of when the petition was filed with USCIS. Please note that approximately 3,000 initial H- 1B petitions are not accounted for on this list due to missing petitioner tax ID numbers. Related Files H-1B Approved Petitioners FY 2009 (1KB CSV) Last updated:01/22/2010 AILA InfoNet Doc. No. 10042060. (Posted 04/20/10) uscis.gov/…/menuitem.5af9bb95919f3… 1/1 5/4/2010 http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resource… NUMBER OF H-1B PETITIONS APPROVED BY USCIS IN FY 2009 FOR INITIAL BENEFICIARIES, EMPLOYER,INITIAL BENEFICIARIES WIPRO LIMITED,"1,964" MICROSOFT CORP,"1,318" INTEL CORP,723 IBM INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED,695 PATNI AMERICAS INC,609 LARSEN & TOUBRO INFOTECH LIMITED,602 ERNST & YOUNG LLP,481 INFOSYS TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED,440 UST GLOBAL INC,344 DELOITTE CONSULTING LLP,328 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED,320 CISCO SYSTEMS INC,308 ACCENTURE TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS,287 KPMG LLP,287 ORACLE USA INC,272 POLARIS SOFTWARE LAB INDIA LTD,254 RITE AID CORPORATION,240 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO,236 DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP,235 COGNIZANT TECH SOLUTIONS US CORP,233 MPHASIS CORPORATION,229 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LIMITED,219 BLOOMBERG,217 MOTOROLA INC,213 GOOGLE INC,211 BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCH SYSTEM,187 UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND,185 UNIV OF MICHIGAN,183 YAHOO INC,183 -

Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey Faqs

Frequently Asked Questions about the Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey Cases and the Netflix Documentary, Making a Murderer What role did the Wisconsin Innocence Project (WIP) play in producing the film? None, other than agreeing to a single interview in late 2005 or early 2006 of WIP co- director Keith Findley. The independent filmmakers asked for no other involvement than that. What role did WIP play in exonerating Steven Avery in the 1985 attempted rape and attempted murder case, for which he served 18 years before DNA proved his innocence? WIP represented Avery in that case and obtained the DNA testing that proved his innocence and identified convicted sex offender Gregory Allen as the true perpetrator. For a description of that case from the perspective of Penny Beerntsen, the victim of that crime, see “Penny Beerntsen, the Rape Victim in ‘Making A Murderer,’ Speaks Out,” https://www.themarshallproject.org/2016/01/05/penny-beernsten-the-rape-victim-in- making-a-murderer-speaks-out#.wem3FlkE8. Did WIP take down Steven Avery’s case from its website after the Halbach murder, and if so, why? After Teresa Halbach’s murder, WIP initially kept Steven Avery’s case on its website because there is no question that he was absolutely innocent of the 1985 crime, we wanted to present an honest accounting of the facts, and we wanted to respect the presumption of innocence to which Avery was entitled in the Halbach murder. Over time, the website became the focus for angry complaints that it was adding insult to the Halbach family’s very tragic loss, and the site was generating considerable anger directed toward Avery. -

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES of WRONGDOING in FILM and LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Norther

ABSTRACT TRUE CRIME DOES PAY: NARRATIVES OF WRONGDOING IN FILM AND LITERATURE Andrew Burt, Ph.D. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2017 Scott Balcerzak, Director This dissertation examines true crime’s ubiquitous influence on literature, film, and culture. It dissects how true-crime narratives affect crime fiction and film, questioning how America’s continual obsession with crime underscores the interplay between true crime narratives and their fictional equivalents. Throughout the 20th century, these stories represent key political and social undercurrents such as movements in religious conservatism, issues of ethnic and racial identity, and developing discourses of psychology. While generally underexplored in discussions of true crime and crime fiction, these currents show consistent shifts from a liberal rehabilitative to a conservative punitive form of crime prevention and provide a new way to consider these undercurrents as culturally-engaged genre directives. I track these histories through representative, seminal texts, such as Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (1925), W.R. Burnett’s Little Caesar (1929, Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952), and Barry Michael Cooper’s 1980s new journalism pieces on the crack epidemic and early hip hop for the Village Voice, examining how basic crime narratives develop through cultural changes. In turn, this dissertation examines film adaptations of these narratives as well, including George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun (1951), Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar (1972), Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me (2010), and Mario Van Peeble’s New Jack City (1991), accounting for how the medium changes the crime narrative. In doing so, I examine true crime’s enduring resonance on crime narratives by charting the influence of commonly overlooked early narratives, such as execution sermons and murder ballads. -

Serial Killers

Abdallah al-Hubal Name(s): al-Hubal, Abdallah Alias: Official bodycount: 13 Location: Yemen Claimed bodycount: 13 Abel Latif Sharif Name(s): Sharif, Abel Latif Alias: El Depredador Psicópata Official bodycount: 1 Location: Mexico and USA Claimed bodycount: 17 Ahmad Suradji Name(s): Suradji, Ahmad Alias: Official bodycount: 42 Location: Indonesia Claimed bodycount: 42 Aileen Wuornos Name(s): Wuornos, Aileen Alias: Official bodycount: 7 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 7 Albert DeSalvo Name(s): DeSalvo, Albert Alias: Boston Strangler, the Official bodycount: 13 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 13 Albert Fish Name(s): Fish, Albert Alias: Gray Man, the Official bodycount: 15 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 15 Ali Reza Khoshruy Kuran Kordiyeh Name(s): Kordiyeh, Ali Reza Khoshruy Kuran Alias: Teheran Vampire, the Official bodycount: 9 Location: Iran Claimed bodycount: 9+ Alton Coleman & Debra Brown Name(s): Coleman, Alton + Brown, Debra Alias: Official bodycount: 8 Location: USA Claimed bodycount: 8 Anatoly Golovkin Name(s): Golovkin, Anatoly Alias: Official bodycount: 11 Location: Russia Claimed bodycount: 11 Anatoly Onoprienko Name(s): Onoprienko, Anatoly Alias: Terminator, the Official bodycount: 52 Location: Ukraine Claimed bodycount: 52 Andonis Daglis Name(s): Daglis, Andonis Alias: Athens Ripper, the Official bodycount: 3 Location: Greece Claimed bodycount: 3 Andras Pandy Name(s): Pandy, Andras Alias: Official bodycount: 6 Location: Belgium Claimed bodycount: 60+ André Luiz Cassimiro Name(s): Cassimiro, André Luiz Alias: Official bodycount: -

Motion for Post Conviction Relief

STATE OF WISCONSIN CIRCUIT COURT MANITOWOC COUNTY STATE OF WISCONSIN, ) ) Respondent ) ) v. ) Case No. 05-CF-1381 ) STEVEN A. AVERY, ) RECEIVED ) Petitioner ) 1JUN O7 2017 CLERK OF ciRc01t CoO RT MANITOWOC COUNTY, WI NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR POST-CONVICTION RELIEF PURSUANT TO WIS. STAT. 974.06 and 805.15 KATHLEEN T. ZELLNER, STEVEN G. RICHARDS Lead Counsel LOCAL COUNSEL DOUGLAS H. JOHNSON Casco, Wisconsin 54205 KATHLEEN T. ZELLNER & (920) 837-2653 ASSOCIATES, P.C. Atty#: 1037545 1901 Butterfield Road, Suite 650 Downers Grove, Illinois 60515 (630) 955-1212 Counsel for Petitioner Local Counsel for Petitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................. .. ..... ........................................................... .i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ... ........ ................... .... ... .. ....................................................... .. ... .. ... x NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR POST-CONVICTION RELIEF PURSUANT TO WIS. STAT.§ 974.06 and§ 805.15 PROCEDUilAL HISTORY ................ .... ...................... ... .. .. ........................ ....................... ......... ! Tria/.... ...................................... ................................................. ............................. .................. ....... 1 Post-Conviction Jvfotion Pursuant to Wis. Stat. § 974.02 ................................................................2 Pro Se Post-Conviction Motion Pursuant to Wis. Stat.§ 974.06 .................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .............. .. ....................... -

Harvey Glatman

Serial Violence Analysis of Modus Operandi and Signature Characteristics of Killers CRC SERIES IN PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF CRIMINAL AND FORENSIC INVESTIGATIONS VERNON J. GEBERTH, BBA, MPS, FBINA Series Editor Practical Homicide Investigation: Tactics, Procedures, and Forensic Techniques, Fourth Edition Vernon J. Geberth The Counterterrorism Handbook: Tactics, Procedures, and Techniques, Third Edition Frank Bolz, Jr., Kenneth J. Dudonis, and David P. Schulz Forensic Pathology, Second Edition Dominick J. Di Maio and Vincent J. M. Di Maio Interpretation of Bloodstain Evidence at Crime Scenes, Second Edition William G. Eckert and Stuart H. James Tire Imprint Evidence Peter McDonald Practical Drug Enforcement, Third Edition Michael D. Lyman Practical Aspects of Rape Investigation: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Fourth Edition Robert R. Hazelwood and Ann Wolbert Burgess The Sexual Exploitation of Children: A Practical Guide to Assessment, Investigation, and Intervention, Second Edition Seth L. Goldstein Gunshot Wounds: Practical Aspects of Firearms, Ballistics, and Forensic Techniques, Second Edition Vincent J. M. Di Maio Friction Ridge Skin: Comparison and Identification of Fingerprints James F. Cowger Footwear Impression Evidence: Detection, Recovery and Examination, Second Edition William J. Bodziak Principles of Kinesic Interview and Interrogation, Second Edition Stan Walters Practical Fire and Arson Investigation, Second Edition David R. Redsicker and John J. O’Connor The Practical Methodology of Forensic Photography, Second Edition David R.