Operation Husky the Campaign in Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coils of the Anaconda: America's

THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN BY C2009 Lester W. Grau Submitted to the graduate degree program in Military History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date defended: April 27, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Lester W. Grau certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN Committee: ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date approved: April 27, 2009 ii PREFACE Generals have often been reproached with preparing for the last war instead of for the next–an easy gibe when their fellow-countrymen and their political leaders, too frequently, have prepared for no war at all. Preparation for war is an expensive, burdensome business, yet there is one important part of it that costs little–study. However changed and strange the new conditions of war may be, not only generals, but politicians and ordinary citizens, may find there is much to be learned from the past that can be applied to the future and, in their search for it, that some campaigns have more than others foreshadowed the coming pattern of modern war.1 — Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

United States Cryptologic History The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park Special series | Volume 12 | 2016 Center for Cryptologic History David J. Sherman is Associate Director for Policy and Records at the National Security Agency. A graduate of Duke University, he holds a doctorate in Slavic Studies from Cornell University, where he taught for three years. He also is a graduate of the CAPSTONE General/Flag Officer Course at the National Defense University, the Intelligence Community Senior Leadership Program, and the Alexander S. Pushkin Institute of the Russian Language in Moscow. He has served as Associate Dean for Academic Programs at the National War College and while there taught courses on strategy, inter- national relations, and intelligence. Among his other government assignments include ones as NSA’s representative to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council, and on the staff of the National Economic Council. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (Top) Navy Department building, with Washington Monument in center distance, 1918 or 1919; (bottom) Bletchley Park mansion, headquarters of UK codebreaking, 1939 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park David Sherman National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History 2016 Second Printing Contents Foreword ................................................................................ -

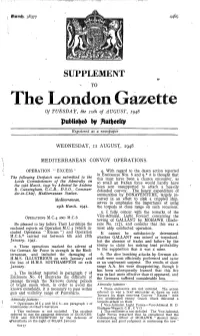

SUPPLEMENT -TO the of TUESDAY, the Loth of AUGUST, 1948

ffhimb, 38377 4469 SUPPLEMENT -TO The Of TUESDAY, the loth of AUGUST, 1948 Registered as a newspaper WEDNESDAY, n AUGUST, 1948 MEDITERRANEAN CONVOY OPERATIONS. OPERATION " EXCESS " 4. With regard to the dawn action reported in Enclosures Nos. 6 and 9,* it is thought that The following Despatch was submitted to the this must have been a chance encounter, as Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty on so small an Italian force would hardly have the igth March, 1941 by Admiral Sir Andrew been sent unsupported to attack a heavily B. Cunningham, G.C.B., D.S.O., Comman- defended convoy. The heavy expenditure of der-in-Chi'ef, Mediterranean Station. ammunition by BON A VENTURE, largely in- Mediterranean, curred in an effort to sink a crippled ship, serves to emphasise the importance of using iqth March, 1941. the torpedo at close range on such occasions. 5. I fully concur with the remarks of the OPERATIONS M.C.4 AND M.C.6 Vice-Admiral, Light Forcesf concerning the towing of GALLANT by MOHAWK (Enclo- Be pleased to lay before Their Lordships the sure No. i if), and consider that this was a enclosed reports on Operation M.C 4 (which in- most ably conducted operation. cluded Operation " Excess ") and Operation It cannot be satisfactorily determined M.C.6,* carried out between 6th and i8th whether GALLANT was mined or torpedoed, January, 1941. but the absence of tracks and failure by the 2. These operations marked the advent of enemy to claim her sinking lend probability the German Air Force in strength in the Medi- to the supposition that it was a mine. -

Air Power and the British Anti-Shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean, 1940-1944

Air Power Review Air Power and the British Anti-Shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean, 1940-1944 By Dr Richard Hammond During the Second World War, the British conducted a sustained campaign of interdiction against Axis supply shipping in the Mediterranean Sea. Air power became a crucial component of this campaign, but was initially highly unsuccessful, delivering few results at a heavy cost. However, a combination of factors, including technical and tactical development, a greater allocation of resources and a higher level of priority being accorded to the campaign, led to vast improvements. By the end of the campaign, the British were conducting highly effective anti-shipping operations, and air power was vital to this in both intelligence gathering and strike roles. 50 British Anti-Shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean Introduction hen Italy declared war on the Allies on 10 June 1940, it placed a heavy burden on Wtheir shipping to supply men and materiel (such as fuel, vehicles, ammunition and food) for their war in North Africa. The Italians and, later, Germans actually required a far greater network of maritime supply in the theatre than just this, however. Positions in Albania and later Greece were supplied through the Adriatic Sea, while territories in the Dodecanese islands required supply in the Aegean. The Aegean was also the route through which tanker traffic brought oil to Italy from the Ploesti fields in Romania.1 Other island territories such as Sardinia, Corsica and Lampedusa were also sustained by maritime supply. Finally, coastal shipping plied routes along the various coasts of North Africa, Italy, France and the Balkans. -

Malta Striking Force By

Malta Striking Force 1941 Malta Striking Force Contents Contents 2 Introduction 3 General Rules 3 Fuel Shortages 3 Night Encounters 3 Table 1 - Royal Navy Striking Force Compositions and Availability 4 Eastern Mediterranean 5 Royal Navy 6 16th April 1941 6 Royal Navy 7 8th/9th November 1941 7 Royal Navy 8 24th November 1941 8 Royal Navy 9 30th November 1941 9 Royal Navy 10 13th December 1941 10 Royal Navy 11 17th December 1941 11 Italian Navy 12 16th April 1941 12 Italian Navy 13 8th/9th November 1941 13 Italian Navy 15 24th November 1941 15 Italian Navy 16 30th November 1941 16 Italian Navy 18 13th December 1941 18 Italian Navy 19 17th December 1941 19 2 Malta Striking Force Introduction Malta Striking force presents a series of linked scenarios which are based on historical actions which took place in the waters of the Mediterranean involving Royal Navy surface forces based at Malta during 1941. At this time Luftwaffe air units had been withdrawn from the central Mediterranean to support the invasions of Greece and Russia, thus enabling significant Royal Navy surface forces to operate from Malta where they could intercept the axis supply lines to North Africa. General Rules The games are to be fought in chronological order, with any ship seriously damaged being ineligible for subsequent actions. The Italian forces are listed for each encounter, but the Royal Navy forces must be selected by the British player specifically for each action. To do this he must choose one or more of the striking forces available at the time of the action. -

Six Victories: North Africa, Malta, and the Mediterranean Convoy War, November 1941–March 1942 by Vincent P

2020-081 9 Sept. 2020 Six Victories: North Africa, Malta, and the Mediterranean Convoy War, November 1941–March 1942 by Vincent P. O’Hara . Annapolis: Naval Inst. Press, 2019. Pp. ix, 322. ISBN 978–1–68247–460–0. Review by Ralph M. Hitchens, Poolesville, MD ([email protected]). North Africa was like an island. [It] produced nothing for the support of armies: every article required for life and war had to be carried there. — I.S.O. Playfair Vincent O‘Hara, a prolific independent scholar of naval warfare,1 ventures deep into the (sea)weeds in his detailed new account of a critical period of the Second World War in the Medi- terranean theater. From the outset, he expects readers to set aside their preconceptions about the Italian armed forces—universally regarded in popular memory as the “weak sister” in the Axis troika. As in his earlier work, he is determined to give the Italian Navy its due. To be sure, it was never a match for the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, but that was owing to a lack of resources. For a time, nonetheless, in a few key engagements, the “Regia Marina” rose to the challenge and accomplished its primary mission: getting convoys across the dangerous waters of the central Mediterranean to supply Gen. Erwin Rommel’s German-Italian Panzerarmee . Military success, the author reminds us, while “often measured in terms of big events” also re- flects the “cumulative impact of little deeds.” Hence, his narrative “may seem full of detail, but detail is the essence of the matter” (2). -

Air Power and the Anti-Shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean, 1940-1944

King’s Research Portal Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hammond, R. J. (2013). Air Power and the British Anti-Shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Air Power Review, 16(1), 50-69. http://www.airpowerstudies.co.uk/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderfiles/aprvol16no1.pdf. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Canadian-Led Raid on Spitzbergen, 1941

Canadian Military History Volume 26 Issue 2 Article 16 2017 Conceiving and Executing Operation Gauntlet: The Canadian-Led Raid on Spitzbergen, 1941 Ryan Dean P. Whitney Lackenbauer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Dean, Ryan and Lackenbauer, P. Whitney "Conceiving and Executing Operation Gauntlet: The Canadian-Led Raid on Spitzbergen, 1941." Canadian Military History 26, 2 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dean and Lackenbauer: Conceiving and Executing Operation Gauntlet Conceiving and Executing Operation Gauntlet The Canadian-Led Raid on Spitzbergen, 1941 RYAN DEAN & P. WHITNEY LACKENBAUER Abstract : In August and September 1941, Canadian Brigadier Arthur Potts led a successful but little known combined operation by a small task force of Canadian, British, and Norwegian troops in the Spitzbergen (Svalbard) archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. After extensive planning and political conversations between Allied civil and military authorities, the operation was re-scaled so that a small, mixed task force would destroy mining and communications infrastructure on this remote cluster of islands, repatriate Russian miners and their families to Russia, and evacuate Norwegian residents to Britain. While a modest non-combat mission, Operation Gauntlet represented Canada’s first expeditionary operation in the Arctic, yielding general lessons about the value of specialized training and representation from appropriate functional trades, unity of command, operational secrecy, and deception, ultimately providing a boost to Canadian morale. -

Toppling the Taliban: Air-Ground Operations in Afghanistan, October

Toppling the Taliban Air-Ground Operations in Afghanistan, October 2001–June 2002 Walter L. Perry, David Kassing C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr381 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Perry, Walter L., author. | Kassing, David, author. Title: Toppling the Taliban : air-ground operations in Afghanistan, October 2001/June 2002 / Walter L. Perry, David Kassing. Other titles: Air-ground operations in Afghanistan, October 2001/June 2002 Description: Santa Monica, CA : RAND, [2015] | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2015044123 (print) | LCCN 2015044164 (ebook) | ISBN 9780833082657 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780833086822 (ebook) | ISBN 9780833086839 (epub) | ISBN 9780833086846 ( prc) Subjects: LCSH: Operation Enduring Freedom, 2001- | Afghan War, 2001---Campaigns. | Afghan War, 2001---Aerial operations, American. | Postwar reconstruction—Afghanistan. Classification: LCC DS371.412 .P47 2015 (print) | LCC DS371.412 (ebook) | DDC 958.104/742—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015044123 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photo by SFC Fred Gurwell, U.S. Army Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. -

British Perceptions of the Italian Navy, 1935-1943

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/07075332.2017.1280520 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hammond, R. (2017). An Enduring Influence on Imperial Defence and Grand Strategy: British Perceptions of the Italian Navy, 1935-1943. INTERNATIONAL HISTORY REVIEW, 39(5), 810-835. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2017.1280520 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Malta| a Study of German Strategy in the Mediterranean, June 1940 to August 1942

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 Malta| A study of German strategy in the Mediterranean, June 1940 to August 1942 Robert Francis Le Blanc The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Le Blanc, Robert Francis, "Malta| A study of German strategy in the Mediterranean, June 1940 to August 1942" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2909. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2909 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MALTA; A STUDY OF GEEMA1Î STRATEGY IN THE MEDITEEEANEAN JUÏÏE 1940 TO AUGUST 1942 By Eotert F. Le Blano B.A., Ifiiiversity of Montana^ I968 Presented in partial fulfiUment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVEESITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved lay; Chairman, Board of Examiners lan, Graduate School ( MaJL ^ Ml') UMI Number: EP34261 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. in the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.