Episode 5, 2006: U.S.S. Indianapolis Cleveland, Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USS Cecil J. Doyle, DE-368 the Destroyer Escort Beacon of Light That Saved Dozens of Drowning Sailors from the Sinking of USS INDIANAPOLIS

USS Cecil J. Doyle, DE-368 The Destroyer Escort Beacon of Light That Saved Dozens of Drowning Sailors From the Sinking of USS INDIANAPOLIS. By Charles "Choppy" Wicker It had been a gruesome four nights and four days since ic bomb core to the B-29 509th Composite Group at two Japanese torpedoes had sunk the USS Indianapolis just Tinian, near Guam. after midnight, on 30 July 1945. Of the 1,197 men on board, about 879 survived the sinking. Injuries, fatigue, That delivery was successful, but in the eleven days starvation, delirium, and of course the sharks, had reduced between delivery and dropping of the bomb on 6 August that number far below 400. Now another night was falling. 1945, the ship was directed to steam to Leyte at normal Nobody had come to the rescue. Nobody else even knew speed. Still under secret orders, the ship was not provided she'd been sunk. with anti-sub escorts. Due to grievous lapses in intelligence and communications, Captain McVay was never informed The USS Indianapolis had been a proud ship. Built in of the possibility of Japanese ships nor submarines being 1930, she was a heavy cruiser,610 feet long, with a dis- anywhere near his route. No escort ships were available. placement of 9,950 tons and a top speed of 32.7 knots. She When he tumed into his sleeping quarters on the night of carried nine 8" main guns and an assortment of secondaries the 29 July, the ship was steaming in relaxed condition at and anti-aircraft guns. -

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with MELVIN C. JACOB Guard, Marine Corps

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with MELVIN C. JACOB Guard, Marine Corps, World War II. 1999 OH 263 1 OH 263 Jacob, Melvin C., (1926- ). Oral History Interview, 1999. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 44 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 44 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Video Recording: 1 videorecording (ca. 44 min.); ½ inch, color. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Melvin C. Jacob, a Manitowoc, Wisconsin native, discusses his World War II service with the Marine Corps aboard the USS Indianapolis . Jacob talks about boot camp at San Diego, brief duty as a guard at a naval prison, and assignment to the USS Indianapolis . Jacob discusses the use of an airplane hanger to hold a heavily guarded box, and comments on later learning that the box held one of the atomic bombs that was dropped on Japan. He describes guard duty and other tasks such as brig watch and gunnery training. After leaving the atomic bomb at Tinian and loading supplies at Guam, he states his ship was heading to the Philippines when it was torpedoed and sunk by a submarine. Jacob describes his actions when the torpedo hit, being told to jump off the boat even though there was no abandon ship order, and finding a life preserver among the debris floating in the water. He reflects on how, though they were supposed to arrive in the Philippines the next day, nobody noticed that they did not get there. -

Titel Taal Auteur ISBN Uitgeverij Jaar

Titel taal auteur ISBN Uitgeverij jaar uitgifte Das grosse Bildbuch der deutschen Kriegsmarine E Bekker Cajus - - 1972 1939-1945 Podvodnye lodki VMF SSSR: spravochnik R Apal'kov Iuri Velentinovich 5-8172-0071-6 - - (submarines of the Soviet navy) Adventure in partnership: the story of Polaris E Watson Cdr.USN Clement Hayes - - - Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol E - - - 1991 IA Der Schiffsmodellbau nach historischen D Lusci vincenzo - - - Vorbildern Das deutsche Unterseeboot U250 D Karschawin Boris A. - - 1994 Das Torpedoarsenal Mitte (TAM) in Rudolstadt D Müller Dr.Klaus W. - - 2007 (Saale), 1942-1945 Das Torpedoarsenal Mitte (TAM) in Rudolstadt D Müller Dr.Klaus W. - - 2007 (Saale), 1942-1945 Das Torpedoarsenal Mitte (TAM) in Rudolstadt D Müller Dr.Klaus W. - - 2007 (Saale), 1942-1945 Orzel: TYPI BRONI UZBROJENIA No.16 Pl - - - - Der Bau von Unterseebooten auf der D Techel Hans - ? 1940 Germaniawerft Der Bau von Unterseebooten auf der D Techel Hans - ? 1969 Germaniawerft La Belle Poule 1765 F Berti Hubert + 2-903179-06-9 A.N.C.R.E. La Belle Poule 1765 F Boudriot Jean + 2-903179-06-9 A.N.C.R.E. La Vénus F Berti Hubert + 2-903179-01-8 A.N.C.R.E. La Vénus F Boudriot Jean + 2-903179-01-8 A.N.C.R.E. Instantaneous echoes E Smith Alastair Carrick 0-9524578-0-6 ACS Publishing 1994 Austro-Hungarian submarines in World War I E Freivogel Zvonimir 978-953-219-339-8 Adamic 2006 Kampf und Untergang der Kriegsmarine D Bekker Cajus - Adolf Sponholtz Verlag 1953 Die deutschen Funklenkverfahren bis 1945 D Trenkle Fritz 3-87087-133-4 AEG - Telefunken AG 1982 Die deutschen Funkpeil- und -Hörch-Verfahren D Trenkle Fritz 3-87087-129-6 AEG - Telefunken AG 1982 bis 1945 Die deutschen Funkstörverfahren bis 1945 D Trenkle Fritz 3-87087-131-8 AEG - Telefunken AG 1982 Die Radargleichung D Gerlitzki Werner Dipl.-Ing. -

Rofworld •WKR II

'^"'^^«^.;^c_x rOFWORLD •WKR II itliiro>iiiiii|r«trMit^i^'it-ri>i«fiinit(i*<j|yM«.<'i|*.*>' mk a ^. N. WESTWOOD nCHTING C1TTDC or WORLD World War II was the last of the great naval wars, the culmination of a century of warship development in which steam, steel and finally aviation had been adapted for naval use. The battles, both big and small, of this war are well known, and the names of some of the ships which fought them are still familiar, names like Bismarck, Warspite and Enterprise. This book presents these celebrated fighting ships, detailing both their war- time careers and their design features. In addition it describes the evolution between the wars of the various ship types : how their designers sought to make compromises to satisfy the require - ments of fighting qualities, sea -going capability, expense, and those of the different naval treaties. Thanks to the research of devoted ship enthusiasts, to the opening of government archives, and the publication of certain memoirs, it is now possible to evaluate World War II warships more perceptively and more accurately than in the first postwar decades. The reader will find, for example, how ships in wartime con- ditions did or did not justify the expecta- tions of their designers, admiralties and taxpayers (though their crews usually had a shrewd idea right from the start of the good and bad qualities of their ships). With its tables and chronology, this book also serves as both a summary of the war at sea and a record of almost all the major vessels involved in it. -

Shokaku Class, Zuikaku, Soryu, Hiryu

ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF KOJINSHA No.6 ‘WARSHIPS OF THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY’ SHOKAKU CLASS SORYU HIRYU UNRYU CLASS TAIHO Translators: - Sander Kingsepp Hiroyuki Yamanouchi Yutaka Iwasaki Katsuhiro Uchida Quinn Bracken Translation produced by Allan Parry CONTACT: - [email protected] Special thanks to my good friend Sander Kingsepp for his commitment, support and invaluable translation and editing skills. Thanks also to Jon Parshall for his work on the drafting of this translation. CONTENTS Pages 2 – 68. Translation of Kojinsha publication. Page 69. APPENDIX 1. IJN TAIHO: Tabular Record of Movement" reprinted by permission of the Author, Colonel Robert D. Hackett, USAF (Ret). Copyright 1997-2001. Page 73. APPENDIX 2. IJN aircraft mentioned in the text. By Sander Kingsepp. Page 2. SHOKAKU CLASS The origin of the ships names. Sho-kaku translates as 'Flying Crane'. During the Pacific War, this powerful aircraft carrier and her name became famous throughout the conflict. However, SHOKAKU was actually the third ship given this name which literally means "the crane which floats in the sky" - an appropriate name for an aircraft perhaps, but hardly for the carrier herself! Zui-kaku. In Japan, the crane ('kaku') has been regarded as a lucky bird since ancient times. 'Zui' actually means 'very lucky' or 'auspicious'. ZUIKAKU participated in all major battles except for Midway, being the most active of all IJN carriers. Page 3. 23 August 1941. A near beam photo of SHOKAKU taken at Yokosuka, two weeks after her completion on 8 August. This is one of the few pictures showing her entire length from this side, which was almost 260m. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections USS

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections USS (United States Ship) Postal Covers Collection USS Postal Covers Collection. Printed material, 1927–1995. 1.33 feet. Subject collection. Postal covers (1927–1995) from United States ships, including cruisers and destroyer escorts. Many of these covers have been cacheted to commemorate historic figures and events, and are postmarked on board the ships. ________________ Box 1 Folder: 1. USS Albany, CA 123 heavy cruiser, 1946-1953. 2. USS Arkansas, CA 34 heavy cruiser, 1937. 3. USS Astoria, CA 34 heavy cruiser, 1934-1941. 4. USS Augusta, CA 31 heavy cruiser, 1932-1995. 5. USS Baltimore, CA 68 heavy cruiser, 1944-1955. 6. USS Boston, CA 69 heavy cruiser, 1943-1955. 7. USS Bremerton, CA 130 heavy cruiser, 1945-1954. 8. USS California, 1939. 9. USS Canberra, CA 70 heavy cruiser, 1943-1946. 10. USS Chester, CA 27 heavy cruiser, 1930-1943. 11. USS Chicago, CA 29 heavy cruiser, 1932-1946. 12. USS Colorado, CA 7 heavy cruiser, 1937. 13. USS Columbus, CA 74 heavy cruiser, 1945-1958. 14. USS Des Moines, C 15 cruiser, 1915-1953. 15. USS Fall River, CA 131 heavy cruiser, 194?. 16. USS Helena, CA 75 heavy cruiser, 1945-1948. 17. USS Houston, 1938. 18. USS Indianapolis, CA 35 heavy cruiser, 1934-1944. 19. USS Los Angeles, CA 135 heavy cruiser, 1945-1962. 20. USS Louisville, CA 28 heavy cruiser, 1934-1945. 21. USS Macon, CA 132 heavy cruiser, 1947-1959. 22. USS Minneapolis, C 13 cruiser, 1918-1945. 23. USS New Orleans, CA 32 heavy cruiser, 1933-1945. -

Priceless Advantage 2017-March3.Indd

United States Cryptologic History A Priceless Advantage U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence and the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Aleutians series IV: World War II | Volume 5 | 2017 Center for Cryptologic History Frederick D. Parker retired from NSA in 1984 after thirty-two years of service. Following his retirement, he worked as a reemployed annuitant and volunteer in the Center for Cryptologic History. Mr. Parker served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1943 to 1945 and from 1950 to 1952. He holds a B.S. from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other U.S. govern- ment entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (l to r) Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief, Japanese Combined Fleet, 1942; aircraft preparing for launch on the USS Enterprise during the Battle of Midway on 4 June 1942 with the USS Pensacola and a destroyer in distance; and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, ca. 1942-1944 A Priceless Advantage: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence and the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Aleutians Frederick D. Parker Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency Reissued 2017 with a new introduction First edition published 1993. -

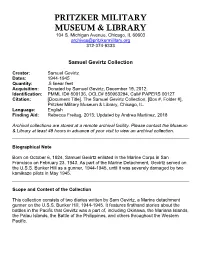

Samuel Gevirtz Collection

PRITZKER MILITARY MUSEUM & LIBRARY 104 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60603 [email protected] 312-374-9333 Samuel Gevirtz Collection Creator: Samuel Gevirtz Dates: 1944-1945 Quantity: .5 linear feet Acquisition: Donated by Samuel Gevirtz, December 19, 2012. Identification: PMML ID# 800136, OCLC# 850963294, Call# PAPERS 00127 Citation: [Document Title]. The Samuel Gevirtz Collection, [Box #, Folder #], Pritzker Military Museum & Library, Chicago, IL. Language: English Finding Aid: Rebecca Freitag, 2013; Updated by Andrea Martinez, 2018 Archival collections are stored at a remote archival facility. Please contact the Museum & Library at least 48 hours in advance of your visit to view an archival collection. Biographical Note Born on October 6, 1924, Samuel Gevirtz enlisted in the Marine Corps in San Francisco on February 23, 1943. As part of the Marine Detachment, Gevirtz served on the U.S.S. Bunker Hill as a gunner, 1944-1945, until it was severely damaged by two kamikaze pilots in May 1945. Scope and Content of the Collection This collection consists of two diaries written by Sam Gevirtz, a Marine detachment gunner on the U.S.S. Bunker Hill, 1944-1945. It features firsthand stories about the battles in the Pacific that Gevirtz was a part of, including Okinawa, the Mariana Islands, the Palau Islands, the Battle of the Philippines, and others throughout the Western Pacific. Arrangement The collection arrived with no discernible arrangement and was rearranged by PMML staff. The collection is contained within 1 slim legal document box and a small flat box. Rights Copyrights held by Sam Gevirtz were transferred to the Pritzker Military Museum & Library. -

Book Review to in Harm's Way: the Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2005 Book Review to In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors Eric R. Carpenter Graduate student, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Admiralty Commons Recommended Citation Eric R. Carpenter, Book Review to In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis and the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors , 2005 Army Law 48 (2005). Available at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications/50 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 2005 Army Law. 48 2005 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Sun Oct 12 19:32:46 2014 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0364-1287 Book Review I IN HARM'S WAY: THE SINKING OF THE USS INDIANAPOLIS AND THE EXTRAORDINARY STORY OF ITS SURVIVORS 2 REVIEWED BY MAJOR ERIC R. CARPENTER On July 30, 1945, just days before the end of World War II, a Japanese submarine sank the USS Indianapolis,directly 4 killing 300 of the ship's 1200-man crew.3 Nine-hundred men entered the water alive. -

USS Indianapolis Papers

USS Indianapolis Papers Collection # SC 2875 USS INDIANAPOLIS PAPERS, 1932–1934 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Paul Brockman January 2011 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 folder COLLECTION: COLLECTION 1932–1934 DATES: PROVENANCE: All acquisition information unknown RESTRICTIONS: None file:///K|/SC%20CG's/SC2875%20USS%20Indpls/SC2875.html[3/4/2011 11:33:51 AM] USS Indianapolis Papers COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED USS Indianapolis Collection, M 0645; Colleen Mondor, USS HOLDINGS: Indianapolis Correspondence, 1995–1996, M 0782 ACCESSION 0000.0844 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH The heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, CA 35, was commissioned in November 1932. It saw its first combat of World War II in the South Pacific Theater in February 1942. The Indianapolis became the flag ship for the 5th Fleet and it saw extensive combat duty in the South Pacific, receiving ten battle stars for action in numerous engagements including the assault on the Marianas ("The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot"), June–August 1944, the covering of the Iwo Jima landings, February–March 1945, and the pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa, March 1945. On 16 July 1945 the ship departed from Mare Island Navy Yard in California on a secret cargo mission to Tinian Island in the Marianas. The cargo mission entailed carrying several parts for the assemblage of the atomic bomb, including uranium. -

USS Indianapolis-Torpedoed in Closing Days of WWII Last Updated Thursday, 27 October 2011 00:48

USS Indianapolis-torpedoed in closing days of WWII Last Updated Thursday, 27 October 2011 00:48 USS Indianapolis (CA-35) was a Portland-class cruiser of the United States Navy. She holds a place in history due to the circumstances of her sinking, which led to the greatest single loss of life at sea in the history of the U.S. Navy. On 30 July 1945, shortly after delivering critical parts for the first atomic bomb to be used in combat to the United States air base at Tinian, the ship was torpedoed by the Imperial Japanese Navy submarine I-58, sinking in 12 minutes. Of 1,196 crewmen aboard, approximately 300 went down with the ship.The remaining crew of 880 men faced exposure, dehydration and shark attacks as they waited for assistance while floating with few lifeboats and almost no food or water. The Navy learned of the sinking when survivors were spotted four days later by the crew of a PV-1 Ventura on routine patrol. Only 316 sailors survived.[2] Indianapolis was the last major U.S. Navy ship sunk by enemy action in World War II. 1945 Overhauled, Indianapolis joined Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher's fast carrier task force on 14 February 1945. Two days later, the task force launched an attack on Tokyo to cover the landings on Iwo Jima, scheduled for 19 February. This was the first carrier attack on Japan since the Doolittle Raid. The mission was to destroy Japanese air facilities and other installations in the "Home Islands". The fleet achieved complete tactical surprise by approaching the Japanese coast under cover of bad weather. -

Carrier Battles: Command Decision in Harm's Way Douglas Vaughn Smith

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Carrier Battles: Command Decision in Harm's Way Douglas Vaughn Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES CARRIER BATTLES: COMMAND DECISION IN HARM'S WAY By DOUGLAS VAUGHN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History, In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Douglas Vaughn Smith defended on 27 June 2005. _____________________________________ James Pickett Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ William J. Tatum Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member _____________________________________ Donald D. Horward Committee Member _____________________________________ James Sickinger Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This work is dedicated to Professor Timothy H. Jackson, sailor, scholar, mentor, friend and to Professor James Pickett Jones, from whom I have learned so much. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Professor Timothy H. Jackson, Director, College of Distance Education, U.S. Naval War College, for his faith in me and his continuing support, without which this dissertation would not have been possible. I also wish to thank Professor James Pickett Jones of the Florida State University History Department who has encouraged and mentored me for almost a decade. Professor of Strategy and Policy and my Deputy at the Naval War College Stanley D.M. Carpenter also deserves my most grateful acknowledgement for taking on the responsibilities of my job as well as his own for over a year in order to allow me to complete this project.