Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University Volume 51 (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season Scheduleschedule

SEASONSEASON SCHEDULESCHEDULE MAY JUNE SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 1 2 3 4 5 @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 DE DE DE DE DE @FAY OFF CAR CAR CAR CAR CAR 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 DE OFF @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY CAR OFF @DE @DE @DE @DE @DE 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 @FAY OFF COL COL COL COL COL @DE OFF FAY FAY FAY FAY FAY 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 COL OFF @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR FAY OFF CSC CSC 30 31 @CAR OFF JULY AUGUST SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 CSC CSC CSC SAL OFF @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 CSC OFF @FBG @FBG @FBG @FBG @FBG @CAR OFF @AUG @AUG @AUG @AUG @AUG 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 @FBG OFF CAR CAR CAR CAR CAR @AUG OFF DE DE DE DE DE 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 CAR OFF @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY DE OFF LY N LY N LY N LY N LY N 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 @FAY OFF SAL SAL SAL SAL SAL LY N OFF @DE SEPTEMBER HOME AWAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY LOW-A EAST 1 2 3 4 DEL DELMARVA SHOREBIRDS @DE @DE @DE @DE FBG FREDERICKSBURG NATIONALS LY N LYNCHBURG HILLCATS 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SAL SALEM RED SOX @DE OFF FAY FAY FAY FAY FAY CAR CAROLINA MUDCATS DE DOWN EAST WOOD DUCKS 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 FAY FAYETTEVILLE WOODPECKERS FAY OFF @COL @COL @COL @COL @COL AUG AUGUSTA GREENJACKETS CSC CHARLESTON RIVERDOGS 19 COL COLUMBIA FIREFLIES @COL MB MYRTLE BEACH PELICANS *ALL DATES AND TIMES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. -

Of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991

Annals of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991 PRESIDENTS RoGERS W. DAvis . .• ........ .. 1916-1918 J. ConDON CHRISTIAN, Jn .......... 1954-1955 DAVID CLARK ....... .. •..• ..... 191 8-1919 ALBERT L. BECHTOLD ........... 1955-1956 JoHN W . Fox ........•.. • ....... 1919-1920 GLENN E. P ARK . .... ......•..... 1956-1957 J. PERRIN QuARLES . ..... ...•... .. 1920-1921 MARSHALL E. LAKE .......•.. ... 1957-1958 LEwis C. BunwELL ...•..•....... 1921-1922 FRANCIS J. BEATTY . ....•. .... ... 1958-1959 J. NoRMAN PEASE . ............. 1922-1923 CHARLES A. HuNTER ... •. .•...... 1959-1960 HowARD M. \ VADE .... .. .. .• ... 1923-1924 EDGAR A. TERRELL, J R ........•.... 1960-1961 J. Wl\1. THOMPSON, Jn . .. .... .. 1924-1925 F. SADLER LovE ... .. ......•...... 1961-1962 HAMILTON C. JoNEs ....... ... .... 1925-1926 M. D . WHISNANT .. .. .. • .. •... 1962-1963 HAMILTON W . McKAY ......... .. 1926-1 927 H . HAYNES BAIRD .... .. •.... .. 1963-1964 HENRY C. McADEN ...... ..•. ... 1927- 1928 TEBEE P. HAWKINS .. ....•. ... 1964-1965 RALSTON M . PouND, Sn. .• . .... 1928- 1929 }AMES R. BRYANT, JR .....•.. •..... 1965-1966 J oHN PAuL LucAs, Sn . ... ... ... 1929-1 930 CHARLES N. BRILEY ......•..•. ... 1966-1967 JuLIAN S. MILLER .......•... .•. .. 1930-193 1 R. ZAcH THOMAS, Jn • . ............ 1967-1968 GEORGE M. lvEY, SR ..... ..... .. 1931-1932 C. GEORGE HENDERSON ... • ..•.. 1968- 1969 EDGAR A. TERRELL, Sn...•........ 1932-1 933 J . FRANK TIMBERLAKE .......... 1969-1970 JuNIUS M . SMITH .......•. ....... 1933-1934 BERTRAM c. FINCH ......•.... ... 1970-1971 }AMES H. VAN NESS ..... • .. .. .. 1934-1935 BARRY G. MILLER .....• ... • .... 1971-1972 RuFus M. J oHNSTON . .•..... .. .. 1935-1936 G. DoN DAviDsoN .......•..•.... 1972-1973 J. A. MAYO "" "."" " .""" .1936-1937 WARNER L. HALL .... ............ 1973-1974 v. K. HART ... ..•.. •. .. • . .•.... 193 7- 1938 MARVIN N. LYMBERIS .. .. •. .... 1974-1975 L. G . OsBORNE .. ..........•.... 1938-1939 THOMAS J. GARRETT, Jn........... 1975-1976 CHARLES H. STONE . ......•.. .... 1939-1940 STUART R. DEWITT ....... •... .. 1976-1977 pAUL R. -

2.28.14 Posting

Updated as of 2/25/14 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Competition Host B/G = Boys Baseball and Girls Softball Divisions Offered G = Only Girls Softball Division Offered B = Only Boys Baseball Division Offered State State City Zip Boys/Girls Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska AK Anchorage 99502 G Alaska ASA (907) 227-7558 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD AK Eielson AFB 99702 B/G Eielson Youth Programs (907) 377-1069 [email protected] TBD TBD Eielson AFB Youth Fields AK Elmendorf AFB 99506 B/G 3 SVS/SVYY - Youth Center/B&GC (907) 552-2266 [email protected] 17-May 10:00am AMC Little League Complex AK Homer 99603 B/G Homer Little League (907) 235-6659 [email protected] 17-May 12:00pm Karen Hornaday Field AK Nikiski 99635 B/G NPRSA (907) 776-6416 [email protected] 31-May 1:00pm NPRSA Alabama AL Alabaster 35007 B/G Alabaster Parks & Recreation (205) 664-6840 [email protected] 22-Mar TBD Veterans Park AL Birmingham 35211 B/G Piper Davis Youth Baseball League (205) 616-3309 [email protected] 29-Mar 9:30am Lowery Park West End AL Demopolis 36732 B/G Synergy Sports Training LLC (334) 289-2255 [email protected] TBD TBD Synergy Sports Field 1 AL Dothan 36302 G Dothan Leisure Services (334) 615-3730 [email protected] TBD TBD Doug Tew Park AL Dothan 36302 B Dothan Leisure Services/Dothan American (334) 615-3730 [email protected] TBD TBD Doug Tew Park AL Dothan 36302 B Dothan -

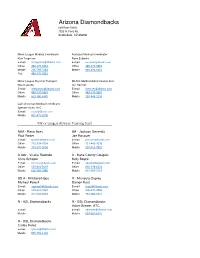

PBATS Directory 4.3.18.Xlsx

Arizona Diamondbacks Salt River Fields 7555 N. Pima Rd. Scottsdale, AZ 85258 Minor League Medical Coordinator Assistant Medical Coordinator Kyle Torgerson Ryne Eubanks E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 480-270-5864 Office 480-270-5863 Mobile 206-799-3584 Mobile 901-270-5251 Fax 480-270-5825 Minor League Physical Therapist ML/MiL Medical Administrative Asst. Max Esposito Jon Herzner E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 480-270-5863 Office 480-270-5863 Mobile 603-380-6345 Mobile 520-444-3154 Latin American Medical Coordinator Spencer Ryan, ATC E-mail [email protected] Mobile 801-473-2006 Minor League Athletic Training Staff AAA - Reno Aces AA - Jackson Generals Paul Porter Joe Rosauer E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 775-334-7034 Office 251-445-2028 Mobile 734-272-3656 Mobile 319-415-7891 A Adv - Visalia Rawhide A - Kane County Cougars Chris Schepel Kelly Boyce E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 559-622-9197 Office 630-578-6254 Mobile 616-566-5486 Mobile 815-560-2716 SS A - Hillsboro Hops R - Missoula Osprey Michael Powell Damon Reel E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 509-452-1849 Office 406-327-0886 Mobile 412-596-4639 Mobile 765-480-5622 R - AZL Diamondbacks R - DSL Diamondbacks Adam Brewer, ATC E-mail E-mail [email protected] Mobile Mobile 607-661-6221 R - DSL Diamondbacks Carlos Perez E-mail [email protected] Mobile 809-781-1101 Atlanta Braves mailing: P.O. -

Kannapolis Cannon Ballers (0-4) Vs

TODAY’S MATCH-UP KANNAPOLIS CANNON BALLERS (0-4) VS. DOWN EAST WOOD DUCKS (4-0) Kannapolis Wood Ducks 0-4 Record 4-0 0-4 Home -- -- Road 4-0 Saturday, May 8th, 2020 - Game #5- 6:00 p.m. - Atrium Health Ballpark, Kannapolis, N.C. L4 Streak W4 L4 Last 5 W4 LHP Bailey Horn (0-0, 0.00) vs. RHP Nick Krauth (0-0, 0.00) L4 Last 10 W4 ..219 Batting Avg. .246 4.75 ERA 3.25 Last Game .925 Fielding Pct. .979 ABOUT LAST NIGHT: The Down East Wood Ducks kept rolling to their 3.5 Runs/Game 6.5 fourth win in-a-row Friday night as they beat the Kannapolis Cannon Team R H E LOB 3 HR 2 13 RBI 18 Ballers 4-2. The Wood Ducks have started the 2021 season on fire as 17 BB 21 Down East 4 11 1 12 58 K 54 they continue to find clutch hits late in games to collect wins. 2 SB 9 Kannapolis 2 6 1 17 STANDINGS IF YOU AIN'T FIRST, YOU'RE LAST: Down East continued to get on WP: B. Anderson (1-0) LP: M. Thompson (0- 1) HR: Acu a (1) TOG: 2:47 ATT: 2,140 W/L PCT. GB the board early as they scored first in the top of the second against ñ North: Lynchburg 4-0 1.000 -- Kannapolis starter Matt Thompson. With one out, Keithron Moss sin- Delmarva 2-1 .667 1.5 gled and advanced to third on a single by José Rodriguez. -

UNCG Mag 2017 Fall Spreads.Pdf

FRED CHAPPELL’S DESTINED TAKING GIANT STEPS, P.1 POETIC SALUTATION P. 12 TO TRANSFORM P. 38 RISING HIGHER FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS FALL 2017 Volume 19, No. 1 MAGAZINE Main Building and students with daisy chains, 1901 A Salutation to the Alma Mater in this Her Birth Year spoken by the community of all students, past, present, and future FRED CHAPPELL We gather to express all gratitude graced this special 125th For those enduring gifts that we received contents anniversary issue with a From the faithful nurturing Motherhood commemorative poem. He Of our University beloved. is the author of nineteen news front volumes of poetry, four This bright threshold of opportunity 2 University and alumni news and notes story collections and eight Opened promiseful new worlds unknown novels. He has received, To an eager community out take among other awards, the Whose pilgrimage had now begun. 8 UNCG Dance students soar in dance by Martha Graham, Bollingen Prize in Poetry, who visited UNCG several times. Aiken Taylor Award in We learned to study varied aspects of Nature, Poetry, T. S. Eliot Prize, To examine every thought as it occurs, the studio Prix du Meilleur Livre To bear us each as a friendly creature 10 Arts and entertainment Étranger from the On watchful terms with the universe. Académie française, Thomas Wolfe Prize, John Here we discovered the persons that we were, Destined to Transform Tyler Caldwell Award and And glimpsed the persons that we might become, 12 For 125 years, this campus has transformed students’ lives, Roanoke-Chowan Poetry Striding a measured thoroughfare has transformed knowledge and, in turn, has helped Prize. -

Gaston Alive – June 2012

Neat& Organized With Total-Garage p10 gastonalive.com 1 Try Our New Onion Soup! ONLY 99¢ I-85 Charlotte Avenue/Hwy. 27 I-85 Wayside Drive Westfield Mall Sake Express Sake Express Central Avenue Wilkinson Blvd. (Hwy 74) Main Street Sake Express Hawthorne Street Future Walgreens N. New Hope Road CVS Park Street (Hwy 273) Franklin Blvd. Mount Holly Belmont Gastonia 349 W. Charlotte Ave. 675 Park Street 116 N. New Hope Road Mount Holly, NC 28120 Belmont, NC 28012 Gastonia, NC 28054 704-827-4819 704-461-0400 704-864-4466 STORE HOURS: Gastonia and Belmont Mon.-Sat. 11:00 a.m.-10:00 p.m. Try Our New Sunday 11:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m. Mt. Holly Tilapia Plate! Mon.-Thurs. 11:00 a.m.-9:00 p.m. Friday 11:00 a.m.-10:00 p.m. Saturday 12:00 p.m.-10:00 p.m. Sunday 12:00 p.m.-9:00 p.m. Check Out The New Sake Ad On Youtube! Visit our new website! www.thesakeexpress.com Buy One • Get One FREE 1/2 OFF Onion Soup Any Entree With Purchase Of of equal or lesser value. $4.00 Or More One coupon per customer please. Cannot be *Belmont And Gastonia Locations Only* combined with any other offer. Does not include One coupon per customer please. Cannot be combinations. Expires 7.15.12. combined with any other offer. Expires 7.15.12. 2 Try Our New Onion Soup! ONLY 99¢ I-85 Charlotte Avenue/Hwy. 27 I-85 Wayside Drive Westfield Mall Sake Express Sake Express Central Avenue Wilkinson Blvd. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title : author : publisher : isbn10 | asin : print isbn13 : ebook isbn13 : language : subject publication date : lcc : ddc : subject : cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii In the Ballpark The Working Lives of Baseball People George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the netLibrary eBook. © 1998 by the Smithsonian Institution All rights reserved Copy Editor: Jenelle Walthour Production Editors: Jack Kirshbaum and Robert A. Poarch Designer: Kathleen Sims Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gmelch, George. In the ballpark : the working lives of baseball people / George Gmelch and J. J. Weiner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1-56098-876-2 (alk. paper) 1. BaseballInterviews 2. Baseball fields. 3. Baseball. I. Weiner, J. J. II. Title. GV863.A1G62 1998 796.356'092'273dc21 97-28388 British Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available A paperback reissue (ISBN 1-56098-446-5) of the original cloth edition Manufactured in the United States of America 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 5 4 3 2 1 The Paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z398.48-1984. For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. -

2019 Media Guide

table of contents CLUB INFORMATION club history & records Front office directory .................................. 4-5 Year-by-year records ......................................30 Ownership/executive bios.......................... 6-8 Year-by-year statistics ...................................31 Club information ..............................................9 RoughRiders timeline ..............................32-37 Dr Pepper Ballpark ...................................10-11 Single-game team records ...........................38 Rangers affiliates............................................12 Single-game individual records ..................39 Single-season team batting records ..........40 COACHES & STAFF Single-season team pitching records .........41 Joe Mikulik (manager) .............................14-15 Single-season individual batting records ......42 Greg Hibbard (pitching coach) ....................16 Single-season individual pitching records ....43 Jason Hart (hitting coach) ............................17 Career batting records ..................................44 Support staff, coaching awards ...................18 Career pitching records ................................45 Notable streaks...............................................46 texas league & OPPONENTS Perfect games and no-hitters ......................47 Texas League info, rules and umpires ........20 Opening Day lineups .....................................48 2018 Texas League standings ......................21 Midseason All-Stars, Futures Game ............49 Amarillo -

Hickory Museum of Art Page 14 - Mouse House / Susan Lenz & One Eared Cow Glass Page 18 - Hickory Museum of Art Cont., Blue Moon Gallery & Asheville Gallery of Art

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 23, No. 1 January 2019 You Can’t Buy It Happy New Year! Artwork, Buffoon, is by Luis Ardila and is part of the exhibit ARTE LATINO NOW 2019 on view at the Max L. Jackson Gallery, Watkins building, Queens University of Charlotte, Charlotte, NC. This is the eighth annual exhibition featuring the exciting cultural and artistic contributions of Latinos in the United States. A reception will be held on January 17, 2019 from 5:30 - 7:30pm. Article is on Page 17. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Queens University of Charlotte - Luis Ardila Page 3 - Karen Burnette Garner & Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - Halsey-McCallum Studio & Whimsy Joy by Roz Page 3 - City of North Charleston Page 5 - Emerge SC Page 4 - Editorial Commentary & City of North Charleston cont. Page 5 - Editorial Commentary cont. Page 6 - Avondale Therapy / Susan Irish Page 6 - Charleston Artist Guild & Gibbes Museum of Art Page 7 - Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Rhett Thurman, Page 8 - Coastal Discovery Museum Page 9 - Art League of Hilton Head x 2 & University of SC - Upstate Anglin Smith Fine Art, Spencer Art Galleries, The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary, Page 11 - University of SC - Upstate cont. & West Main Artists Co-op & Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery Page 12 - West Main Artists Co-op, Converse College & Page 8 - Art League of Hilton Head USC-Upstate / UPSTATE Gallery on Main Page 13 - USC-Upstate / UPSTATE Gallery on Main cont. -

The Web Magazine 1979, November/December

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The eW b Magazine Gardner-Webb Publications 1979 The eW b Magazine 1979, November/December Debbie B. Putnam Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/the-web Recommended Citation Putnam, Debbie B., "The eW b Magazine 1979, November/December" (1979). The Web Magazine. 94. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/the-web/94 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Gardner-Webb Publications at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The eW b Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •mf Volume XIII, No. 2 "<=&*■ «« be* exeitzd of oat tAz yxowtA and dzuzfofimznt of tAz dotfzgz 's fixoyxams on so many fronts, wz Aauz aff trzzn ozxy mucA auraxz of tAz fact tAat tAz cAatfzngz of tAz donoocation dzntzx Aas stood as tAz ftaysAifi of tAz zntixz fixoyxam. " fPxzsudznt dxavzn iff Lams Groundbreaking Ceremonies Held! Under cloudy and slightly threatening remarks from College President Craven in total giving to the College, an increase important one for us. The completion weather conditions on October 20th, E. Williams initiated the series of events from 43% to 70% in faculty earned of this building will fill a void in the life several hundred persons observed preceeding the actual groundbreaking. doctorates, a 22 % increase in library of this campus as broad and desolate as groundbreaking ceremonies for Rev. Richard McBride, Campus Minister holdings and more than a quarter of a this barren ground is now. -

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Name PGCBL Team (Year)

The Perfect Game Collegiate Baseball League (PGCBL), upstate New York’s premier summer wood bat league, played its seventh season in 2017. Every year since its inception in 2011, the PGCBL has sent players to the pros and has had several alumni selected in the MLB Draft with each year. Here is a list of former PGCBL players that are currently in professional baseball, listed by their current level. MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Name PGCBL Team (Year) MLB Team Hunter Pence Schenectady Mohawks* (2002) San Francisco Giants Shae Simmons Watertown Wizards (2010) Seattle Mariners J.D. Martinez Saratoga Phillies+ (2009) Detroit Tigers Mike Fiers Saratoga Phillies+ (2009) Houston Astros Luke Maile Amsterdam Mohawks (2010-11) Toronto Blue Jays Tom Murphy Oneonta Outlaws (2010) Colorado Rockies James Hoyt Little Falls Miners^ (2008) Houston Astros Nick Pivetta Glens Falls Golden Eagles# (2012) Philadelphia Phillies Mark Leiter Jr. Amsterdam Mohawks (2011-12) Philadelphia Phillies Jimmy Yacabonis Elmira Pioneers (2012) Baltimore Orioles Carlos Asuaje Oneonta Outlaws (2011) San Diego Padres Tim Locastro Newark Pilots (2013) Los Angeles (NL) Two former PGCBL pitchers made their MLB debuts with the Philadelphia Phillies in 2017. Nick Pivetta (L), a former Glens Falls Golden Eagle, was called up on April 30 to face the Dodgers in Los Angeles and struck out five in 5.0 innings in his first start. He would pick up his first major league victory on June 5 in Atlanta. Mark Leiter Jr. (R), a member of the Amsterdam Mohawks Hall of Fame, also made his MLB debut in Los Angeles out of the bullpen on April 28.