Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University Volume 49 (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dan Mintner Badass for Hire V 2.Fdr Script

DAN MINTER: BADASS FOR HIRE Screenplay by Chad Kultgen NOTE: DO NOT TURN THE PAGE UNLESS YOU HAVE NO RESPECT FOR YOUR OWN ASS BECAUSE IT’S ABOUT TO BE KICKED. 2. FADE IN: INT. WAREHOUSE/FACTORY, SOUTH AMERICA - DAY Candy Cane, Wacky Dust, Weasel Dust, Angie, Bernice, Aunt Nora, Barbs, Bazooka, Nose Candy, Bubble Gum, Carnie, Carie Nation, Foo-Foo Dust, Gift of the Sun, Cecil, Bernie, Billy Hoke, Henry VIII, Ice, Jelly, Lady, Girl, Merk, Pearl, Pimp, Schmeck, Scottie, Scorpion, Teeth, Snort, Blow, Snow, Con- Con... CO-MOTHERFUCKING-CAINE. Mountains of the shit as far as the eye can see loom over dozens of scurrying SOUTH AMERICAN COCAINE FACTORY WORKERS in a giant warehouse/cocaine factory. They weigh it, cut it, package it, etc. as they navigate the narrow walkways between the massive mounds. P.S. They’re all carrying machine guns. From a perch high above the workers, in a plush office with big screen TV’s, a fat South American COCAINE KINGPIN keeps a proud but watchful gaze over his empire. With him is a SLEEZY AMERICAN DRUG BUYER. COCAINE KINGPIN As you can see, my operation is large enough to meet any demand. SLEEZY AMERICAN DRUG BUYER But large isn’t always good. Too many people under you... How do you know they’re all loyal? The Cocaine Kingpin’s scowl might as well turn into a boot that kicks the Sleezy American Drug Buyer right in the nuts, but instead, he reigns it in and it turns into a knowing smile. COCAINE KINGPIN Loyalty, my friend, is something you Americans know little about and that’s why you always question it. -

BUILDING Bridges to a Better Economy Viewfinder Ll 2007 Fa Eastthe Magazine of East Carolina University

2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy BUILDING BrIDGes to a better economy vIewfINDer 2007 LL fa EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy 12 feaTUres BUilDing BriDges 12 Creating more jobs is the core of the university’s newBy Steve focus Tuttle on economic development. From planning a new bridge to the Outer Banks to striking new partnerships with relocating companies, ECU is helping the region traverse troubled waters. TUrning The PAGE 18 Shirley Carraway ’75 ’85 ’00 rose steadily in her careerBy Suzanne in education Wood from teacher to principal to superintendent. “I’ve probably changed my job every four or five years,” she says. 18 22 “I’m one of those people who like a challenge.” TeaChing sTUDenTs To SERVE 22 Professor Reginald Watson ’91 is determined toBy walkLeanne the E. walk,Smith not just talk the talk, about the importance of faculty and students connecting with the community. “We need to keep our feet in the world outside this campus,” he says. FAMILY feUD 26 As another football game with N.C. State ominouslyBy Bethany Bradsher approaches, Skip Holtz is downplaying the importance of the contest. And just as predictably, most East Carolina fans are ignoring him. DeParTMeNTs froM oUr reaDers 3 The eCU rePorT 4 26 FALL arTs CalenDar 10 BookworMs PiraTe naTion Dowdy student stores stocks books 34 for about 3,500 different courses and expects to move about one million textbooks into the hands of students during the hectic first CLASS noTes weeks of fall semester. Jennifer Coggins and Dwayne 37 Murphy are among several students who worked this summer unpacking and cataloging thousands of boxes of new books. -

Season Scheduleschedule

SEASONSEASON SCHEDULESCHEDULE MAY JUNE SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 1 2 3 4 5 @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 DE DE DE DE DE @FAY OFF CAR CAR CAR CAR CAR 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 DE OFF @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY CAR OFF @DE @DE @DE @DE @DE 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 @FAY OFF COL COL COL COL COL @DE OFF FAY FAY FAY FAY FAY 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 COL OFF @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR FAY OFF CSC CSC 30 31 @CAR OFF JULY AUGUST SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 CSC CSC CSC SAL OFF @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR @CAR 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 CSC OFF @FBG @FBG @FBG @FBG @FBG @CAR OFF @AUG @AUG @AUG @AUG @AUG 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 @FBG OFF CAR CAR CAR CAR CAR @AUG OFF DE DE DE DE DE 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 CAR OFF @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY @FAY DE OFF LY N LY N LY N LY N LY N 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 @FAY OFF SAL SAL SAL SAL SAL LY N OFF @DE SEPTEMBER HOME AWAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY LOW-A EAST 1 2 3 4 DEL DELMARVA SHOREBIRDS @DE @DE @DE @DE FBG FREDERICKSBURG NATIONALS LY N LYNCHBURG HILLCATS 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SAL SALEM RED SOX @DE OFF FAY FAY FAY FAY FAY CAR CAROLINA MUDCATS DE DOWN EAST WOOD DUCKS 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 FAY FAYETTEVILLE WOODPECKERS FAY OFF @COL @COL @COL @COL @COL AUG AUGUSTA GREENJACKETS CSC CHARLESTON RIVERDOGS 19 COL COLUMBIA FIREFLIES @COL MB MYRTLE BEACH PELICANS *ALL DATES AND TIMES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. -

Of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991

Annals of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991 PRESIDENTS RoGERS W. DAvis . .• ........ .. 1916-1918 J. ConDON CHRISTIAN, Jn .......... 1954-1955 DAVID CLARK ....... .. •..• ..... 191 8-1919 ALBERT L. BECHTOLD ........... 1955-1956 JoHN W . Fox ........•.. • ....... 1919-1920 GLENN E. P ARK . .... ......•..... 1956-1957 J. PERRIN QuARLES . ..... ...•... .. 1920-1921 MARSHALL E. LAKE .......•.. ... 1957-1958 LEwis C. BunwELL ...•..•....... 1921-1922 FRANCIS J. BEATTY . ....•. .... ... 1958-1959 J. NoRMAN PEASE . ............. 1922-1923 CHARLES A. HuNTER ... •. .•...... 1959-1960 HowARD M. \ VADE .... .. .. .• ... 1923-1924 EDGAR A. TERRELL, J R ........•.... 1960-1961 J. Wl\1. THOMPSON, Jn . .. .... .. 1924-1925 F. SADLER LovE ... .. ......•...... 1961-1962 HAMILTON C. JoNEs ....... ... .... 1925-1926 M. D . WHISNANT .. .. .. • .. •... 1962-1963 HAMILTON W . McKAY ......... .. 1926-1 927 H . HAYNES BAIRD .... .. •.... .. 1963-1964 HENRY C. McADEN ...... ..•. ... 1927- 1928 TEBEE P. HAWKINS .. ....•. ... 1964-1965 RALSTON M . PouND, Sn. .• . .... 1928- 1929 }AMES R. BRYANT, JR .....•.. •..... 1965-1966 J oHN PAuL LucAs, Sn . ... ... ... 1929-1 930 CHARLES N. BRILEY ......•..•. ... 1966-1967 JuLIAN S. MILLER .......•... .•. .. 1930-193 1 R. ZAcH THOMAS, Jn • . ............ 1967-1968 GEORGE M. lvEY, SR ..... ..... .. 1931-1932 C. GEORGE HENDERSON ... • ..•.. 1968- 1969 EDGAR A. TERRELL, Sn...•........ 1932-1 933 J . FRANK TIMBERLAKE .......... 1969-1970 JuNIUS M . SMITH .......•. ....... 1933-1934 BERTRAM c. FINCH ......•.... ... 1970-1971 }AMES H. VAN NESS ..... • .. .. .. 1934-1935 BARRY G. MILLER .....• ... • .... 1971-1972 RuFus M. J oHNSTON . .•..... .. .. 1935-1936 G. DoN DAviDsoN .......•..•.... 1972-1973 J. A. MAYO "" "."" " .""" .1936-1937 WARNER L. HALL .... ............ 1973-1974 v. K. HART ... ..•.. •. .. • . .•.... 193 7- 1938 MARVIN N. LYMBERIS .. .. •. .... 1974-1975 L. G . OsBORNE .. ..........•.... 1938-1939 THOMAS J. GARRETT, Jn........... 1975-1976 CHARLES H. STONE . ......•.. .... 1939-1940 STUART R. DEWITT ....... •... .. 1976-1977 pAUL R. -

Riley Thorn and the Dead Guy Next Door

RILEY THORN AND THE DEAD GUY NEXT DOOR LUCY SCORE Copyright © 2020 Lucy Score All rights reserved No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electric or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without prior written permission from the publisher. The book is a work of fiction. The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author. ISBN: 978-1-945631-67-2 (ebook) ISBN: 978-1-945631-68-9 (paperback) lucyscore.com 082320 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Epilogue Author’s Note to the Reader WONDERING WHAT TO READ NEXT?: About the Author Acknowledgments Lucy’s Titles To Josie, a real life badass. 1 10:02 p.m., Saturday, July 4 he dead talked to Riley Thorn in her dreams. -

Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019

Saturday 18th May 2019 | 10:00 Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019 Lot 19 Description Estimate 5 x Doo Wop / RnB / Pop 7" singles. The Temptations - Someday (Goldisc £15.00 - £25.00 3001). The Righteous Brothers - Along Came Jones (Verve VK-10479). The Jesters - Please Let Me Love You (Winley 221). Wayne Cochran - The Coo (Scottie 1303). Neil Sedaka - Ring A Rockin' (Guyden 2004) Lot 93 Description Estimate 10 x 1980s LPs to include Blondie (2) Parallel Lines, Eat To The Beat. £20.00 - £40.00 Ultravox (2) Vienna, Rage In Eden (with poster). The Pretenders - 2. Men At Work - Business As Usual. Spandau Ballet (2) Journeys To Glory, True. Lot 94 Description Estimate 5 x Rock n Roll 7" singles. Eddie Cochran (2) Three Steps To Heaven £15.00 - £25.00 (London American Recordings 45-HLG 9115), Sittin' On The Balcony (Liberty F55056). Jerry Lee Lewis - Teenage Letter (Sun 384). Larry Williams - Slow Down (Speciality 626). Larry Williams - Bony Moronie (Speciality 615) Lot 95 Description Estimate 10 x 1960s Mod / Soul 7" Singles to include Simon Scott With The LeRoys, £15.00 - £25.00 Bobby Lewis, Shirley Ellis, Bern Elliot & The Fenmen, Millie, Wilson Picket, Phil Upchurch Combo, The Rondels, Roy Head, Tommy James & The Shondells, Lot 96 Description Estimate 2 x Crass LPs - Yes Sir, I Will (Crass 121984-2). Bullshit Detector (Crass £20.00 - £40.00 421984/4) Lot 97 Description Estimate 3 x Mixed Punk LPs - Culture Shock - All The Time (Bluurg fish 23). £10.00 - £20.00 Conflict - Increase The Pressure (LP Mort 6). Tom Robinson Band - Power In The Darkness, with stencil (EMI) Lot 98 Description Estimate 3 x Sub Humanz LPs - The Day The Country Died (Bluurg XLP1). -

Using the Butterflies in My Stomach

Becoming-Roller Derby: Women, Sport, and the Affects of Power Author Pavlidis, Adele Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Department of Tourism, Sport and Hotel Management DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1342 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366936 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Becoming-Roller Derby: Women, Sport, and the Affects of Power Adele Pavlidis BA (Hons) Department of Tourism, Sport and Hotel Management (Gold Coast, Australia) Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2013 ii Abstract This project is centrally concerned with (re)writing and (re)conceptualising a feminist cultural imaginary for sport and physical culture. Focusing on roller derby as a ‘new’ sport played predominantly by women, I examine the various affects in circulation, both on and off the track, and what these affects do. Thinking through affects, I highlight the processes of transformation that women undergo through roller derby and the challenges of sustaining this kind of cultural space into the future. In doing so, I have written of women in their multiplicity, drawing on post-structural conceptualisations of subjectivity and recent socio-cultural theorising of affects. I acknowledge the challenges of women coming together to pursue a shared goal, yet the project is a hopeful one, in which I offer alternatives to reductionist thinking or biological determinism. Conceptualisations of sport and leisure as ‘empowering’ or necessarily ‘resistant’ for women are questioned throughout this thesis. -

The Pacifier

The Pacifier by Thomas Lennon & Robert Ben Garant Previous Revisions by Jason Fulardi & Scott Alexander & Larry Karaszewki Current Revisions by Thomas Lennon & Robert Ben Garant Marked Revisions * March 3rd, 2004 FADE IN: EXT. PACIFIC OCEAN - DAY A fishing boat pushes over choppy water. FOUR GUN TOTING MEN on Jet Skis wearing black wet suits and goggles escort the boat. Flying above it is a HELICOPTER. INT. FISHING BOAT/CONTROL DECK - CONTINUOUS A SERBIAN MAN captains the wheel. SERB 2 scans the horizon with binoculars. He checks the GPS system, then his watch, then speaks into his throat mic. All italics are Serbian w/ subtitles: SERB 2 Fifteen minutes to delivery. EXT. PACIFIC OCEAN - CONTINUOUS The JET SKIER in the lead weighs in on a radio. INT. SEA HAWK 1 - CONTINUOUS The HELICOPTER PILOT weighs in. PILOT All clear from above. EXT. SKY - CONTINUOUS The camera descends as the boat passes, and dives beneath the surface. EXT. PACIFIC OCEAN - CONTINUOUS The droning of engines becomes less pronounced. Foam from the boat and skis bubbles. Calm. Then from out of nowhere five NAVY SEALs wearing RE- BREATHERS appear, in neat formation like the Blue Angels. JET PROPELLED BACKPACKS push the SEALs through the water. The LEAD SEAL: SHANE WOLFE, points upwards. All eyes follow his finger to the underbelly of the boat above. From his belt, Shane takes a steel wand with an adhesive disc attached, aims it at the fleeing boat and FIRES. A cable shoots up -- THUD... The disc sticks to the boat’s hull. Shane pushes a button on the wand retracting the cable and drawing himself closer. -

This Is Davidson College

General Information Table of Contents 2009 Schedule Athletic Honors . .IBC Davidson College . .17-19 Jan. 23 vs. Boston University 1 5:00 Davidson Quick Facts . .1 Surrounding Area . .20-21 24 at Brown 2:00 2009 Schedule . .1 Strength & Conditioning 22-23 25 at Boston College 11:00 a.m. Athletic Facilities . .24-25 2009 Roster/Team Photo . .2 Feb. 1 #69 Radford 1:00 Academics . .26-27 2009 Outlook . .3 7 at #55 South Carolina 10:00 a.m. Player Profiles . .4-7 Student Life . .28-29 10 Gardner-Webb 4:00 Class of 2008 . .8 Athletic Directory . .30-31 14 USC Upstate 10:00 a.m. Head Coach Barrett . .9 Conference Affiliations . .32 27 Richmond TBA This is Davidson . .IFC Assistant Coach . .9 Mar. 1 at Samford * 12:00 2008 Statistics/Results . .10 3 at Chattanooga * 2:30 2009 Opponents . .12 12 Indiana State 2:30 Year-By-Year Results . .13-15 21 at #70 Furman * 1:30 Honors & Awards . .16 23 U. of Illinois at Chicago 2:00 28 UNC Greensboro * 1:00 2009 M. TENNIS QUICK FACTS Apr. 1 Elon * 3:00 4 at College of Charleston * 1:00 General Information 5 at Georgia Southern * 12:00 8 Wofford * 3:00 School Name . .Davidson College 10 Charlotte 3:00 Location . .Davidson, N.C. 11 at The Citadel * 11:00 a.m. Founded . .1837 16 Appalachian State * (Senior Day) 2:30 Enrollment . .1,700 Nickname . .Wildcats Southern Conference Tournament - Elon, N.C. School Colors . .Red (PMS 186) and Black Nov. 23-26 SoCon Tournament TBD Conference . .Southern Affiliation . -

2.28.14 Posting

Updated as of 2/25/14 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Competition Host B/G = Boys Baseball and Girls Softball Divisions Offered G = Only Girls Softball Division Offered B = Only Boys Baseball Division Offered State State City Zip Boys/Girls Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska AK Anchorage 99502 G Alaska ASA (907) 227-7558 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD AK Eielson AFB 99702 B/G Eielson Youth Programs (907) 377-1069 [email protected] TBD TBD Eielson AFB Youth Fields AK Elmendorf AFB 99506 B/G 3 SVS/SVYY - Youth Center/B&GC (907) 552-2266 [email protected] 17-May 10:00am AMC Little League Complex AK Homer 99603 B/G Homer Little League (907) 235-6659 [email protected] 17-May 12:00pm Karen Hornaday Field AK Nikiski 99635 B/G NPRSA (907) 776-6416 [email protected] 31-May 1:00pm NPRSA Alabama AL Alabaster 35007 B/G Alabaster Parks & Recreation (205) 664-6840 [email protected] 22-Mar TBD Veterans Park AL Birmingham 35211 B/G Piper Davis Youth Baseball League (205) 616-3309 [email protected] 29-Mar 9:30am Lowery Park West End AL Demopolis 36732 B/G Synergy Sports Training LLC (334) 289-2255 [email protected] TBD TBD Synergy Sports Field 1 AL Dothan 36302 G Dothan Leisure Services (334) 615-3730 [email protected] TBD TBD Doug Tew Park AL Dothan 36302 B Dothan Leisure Services/Dothan American (334) 615-3730 [email protected] TBD TBD Doug Tew Park AL Dothan 36302 B Dothan -

PBATS Directory 4.3.18.Xlsx

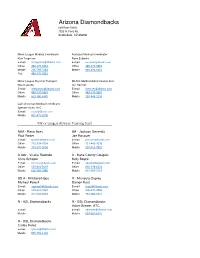

Arizona Diamondbacks Salt River Fields 7555 N. Pima Rd. Scottsdale, AZ 85258 Minor League Medical Coordinator Assistant Medical Coordinator Kyle Torgerson Ryne Eubanks E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 480-270-5864 Office 480-270-5863 Mobile 206-799-3584 Mobile 901-270-5251 Fax 480-270-5825 Minor League Physical Therapist ML/MiL Medical Administrative Asst. Max Esposito Jon Herzner E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 480-270-5863 Office 480-270-5863 Mobile 603-380-6345 Mobile 520-444-3154 Latin American Medical Coordinator Spencer Ryan, ATC E-mail [email protected] Mobile 801-473-2006 Minor League Athletic Training Staff AAA - Reno Aces AA - Jackson Generals Paul Porter Joe Rosauer E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 775-334-7034 Office 251-445-2028 Mobile 734-272-3656 Mobile 319-415-7891 A Adv - Visalia Rawhide A - Kane County Cougars Chris Schepel Kelly Boyce E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 559-622-9197 Office 630-578-6254 Mobile 616-566-5486 Mobile 815-560-2716 SS A - Hillsboro Hops R - Missoula Osprey Michael Powell Damon Reel E-mail [email protected] E-mail [email protected] Office 509-452-1849 Office 406-327-0886 Mobile 412-596-4639 Mobile 765-480-5622 R - AZL Diamondbacks R - DSL Diamondbacks Adam Brewer, ATC E-mail E-mail [email protected] Mobile Mobile 607-661-6221 R - DSL Diamondbacks Carlos Perez E-mail [email protected] Mobile 809-781-1101 Atlanta Braves mailing: P.O. -

The New Country Doctors How ECU Health Care Grads Are Caring for Small-Town Families VIEWFINDER 7 WINTER 200 ETHE Magazinea of EAST Carolinas Universityt

7 WINTER 200 ETHE MAGAZINEa OF EAST CAROLINAs UNIVERSITYt The New Country Doctors How ECU health care grads are caring for small-town families VIEWFINDER 7 WINTER 200 ETHE MAGAZINEa OF EAST CAROLINAs UNIVERSITYt F E A T U R E S THE NEW COUNTRY DOCTORS 12 18 12 The doctors, nurses and allied health care prByof Steessionalsve Row that ECU has sent into eastern North Carolina are improving lives and providing the “boots on the ground” that experts say are the critical front line of health care. THE MISCAST MARTYR OF STUDENT RIGHTS 18 Robert Thonen, the conservative editor of the studentBy Steve Tnewspaperuttle who got himself kicked out of college over a four-letter word, was an unlikely ! gure to be at center stage during the protests that shook ECU 35 years ago. FOOD FOR THOUGHT 24 Remember the free spaghetti dinners at the BaptistBy Betha nStudenty Bradsh eUnion?r They’re still going, and students still are seeking out a safe haven from the wild side of campus life. BUILDING THE TRIANGLE 28 Charles Hayes, a member of the small but powerful gByroup Steve that Tuttle has propelled North Carolina’s economy into the 21st century, doesn’t run an employment agency, but he helped 40,000 people ! nd jobs in the past year. BANANAS OVER BASKETBALL 24 32 They were born the night ECU upset No. 9 MarBy Bethanquettey Br inadsher bask etball, and four years later the Minges Maniacs are still giving the Pirates a home-court advantage. D E P A R T M E N T S FROM OUR READERS 3 THE ECU REPORT 4 32 Petite Pirates and a pony As fl oats fi lled with students FROM THE CLASSROOM rolled down Fifth Street during the 36 Homecoming parade, two petite Pirates showed their excitement by sharing a hug with a pony CLASS NOTES named Lightning.