Download Full Text (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement Issues and the Relationship Between Media Freedom and Corruption

Measurement Issues and the Relationship Between Media Freedom and Corruption By Lee B. Becker University of Georgia, USA ([email protected]) Teresa K. Naab Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien, Hannover, Germany ([email protected]) Cynthia English Gallup, USA ([email protected]) Tudor Vlad University of Georgia, USA ([email protected]) Direct correspondence to: Dr. Lee B. Becker, Grady College of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Georgia, 120 Hooper St., Athens, GA 30602 USA Abstract Advocates for media freedom have consistently argued that corruption goes down when journalists operating in a free media environment are able to expose the excesses of governmental leaders. An evolving body of research finds evidence to support this assertion. Measurement of corruption is a complicated undertaking, and it has received little attention in this literature. This paper focuses on perceptual measures of corruption based on public opinion surveys. It attempts to replicate the finding of a negative relationship between media freedom and corruption using multiple measures of media freedom. The findings challenge the general argument that media freedom unambiguously is associated with lower levels of corruption. Presented to the Journalism Research and Education Section, International Association for Media and Communication Research, Dublin, Ireland, June 25-29, 2013. -1- Measurement Issues and the Relationship Between Media Freedom and Corruption Advocates for media freedom have consistently argued that corruption goes down when journalists operating in a free media environment are able to expose the excesses of governmental leaders. Indeed an evolving body of research finds evidence of a negative relationship between media freedom and level of corruption of a country even when controlling for several other political, social and economic characteristics of the country. -

Sunshine in Korea

CENTER FOR ASIA PACIFIC POLICY International Programs at RAND CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Center for Asia Pacific Policy View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. The monograph/report was a product of the RAND Corporation from 1993 to 2003. RAND monograph/reports presented major research findings that addressed the challenges facing the public and private sectors. They included executive summaries, technical documentation, and synthesis pieces. Sunshine in Korea The South Korean Debate over Policies Toward North Korea Norman D. -

KOREA Culture Shock!

CULTURAL RESOURCES: KOREA Culture Shock! A Guide to Customs and Etiquette: Korea, Times Editions Pte Ltd, Times Centre, 1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 53196 and Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company, PO Box 10306, Portland, Oregon 97210 (503) 226-2402. Communication Styles in Two Different Cultures: Korean and American by Myung- Seok Park, ISBN 89-348-0358-4 Paul Kim, Manager for International Programs, Korea, tells us that this book is about common problems in communication between Americans and Koreans. He said it made him “roll with laughter.” On the back cover the Korean author notes that, when he once made a speech praising one of his professors at a luncheon in her honor, he felt as if he had committed a crime. He had said, “I want to thank you for the energy you have devoted to us in spite of your great age.” He knew he had done something wrong when he saw the corners of his professor’s mouth twitch. The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History by Don Obendorfer Paul Kim also recommends this book. He said it gives good insights into the reasons for the present tensions between North and South Korea, explains why the country is still separated and has been unable to re-unite, and explains the different thought patterns between North and South Koreans. Foster, Jenny, Stewart, Frank, and Fenkl, Heinz, editors, The Century of the Tiger: One Hundred Years of Korean Culture in America, 1903-2003. University of Hawaii Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8248-2644-2 “An outstanding collection of stories and pictures [that] describes the unique and abiding -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

2018-05-Ma-Yang.Pdf

RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF ENGLISH IDEOLOGY IN GLOBALIZING SOUTH KOREA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Seung Woo Yang Thesis Committee: Young-A Park, Chairperson Cathryn Clayton Patricia Steinhoff Keywords: Korean, English, Globalization, English Ideology, National Competitiveness i ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many individuals and organizations I would like to thank for this academic and personal undertaking. The Center for Korean Studies was a big reason why I chose UH Manoa. I owe a great appreciation to the Center for Korean Studies for the remarkable events as well as the opportunity to serve as a graduate assistant. Not only the position provided financial assistance, but I am truly greatful for the learning opportunities it presented. I am also thankful for the opportunity to present this thesis at the Center for Korean Studies. Thank you Director Sang-Hyup Lee, Professor Tae-ung Baik, Mercy, and Kortne for welcoming me into the Center. Thank you, the East-West Center, particularly Dr. Ned Shultz and Kanika Mak-Lavy, for not only the generous funding, but for providing an outside-the-classroom learning that truly enhanced my graduate studies experience. The East-West Center provided the wonderful community and a group of friends where I can proudly say I belong. Thank you Mila and Fidzah. I jokingly believe that I did not finish my thesis on time because of you guys. But I credit you guys for teaching me and redefining the value of trust, generosity, and friendship. -

South Korea Report

Sustainable Governance Indicators SGI 2014 South Korea Report Thomas Kalinowski, Sang-young Rhyu, Aurel Croissant (Coordinator) SGI 2014 | 2 South Korea report Executive Summary The period under assessment covers the final two years of Lee Myung-bak’s Grand National Party (GNP) administration and the first two months of the Park Geun- hye’s newly elected administration under the same party – renamed the Saenuri Party. President Park was elected in December 2012 with 51.6% of the popular vote. It is almost impossible to evaluate the governance capacity of the new administration due to the long transition period between governments, which involved many institutional and personnel changes. Even in May 2013, for example, many positions in high level government offices remain vacant. Therefore this report largely focuses on the last two years of the Lee administration, which was characterized by an extraordinarily long lame-duck period in which few institutional changes occurred and few new policy initiatives were initiated. Despite having a majority in the newly elected National Assembly, Lee’s conservative GNP has gradually shifted support to its new party chairwoman Park over the last two years. In February 2012, the GNP renamed itself the Saenuri Party in an attempt to distance itself from the unpopular President Lee. The Lee administration also lacked popular support due to its perceived failure to revive the economy, increasing social inequality in Korea, huge corruption among the president’s closest aides, and revelations of extensive illegal wire tapping and political investigations. Civil activists also criticized the use of authoritarian measures to stifle political opposition, civil society and media. -

Predators 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PREDATORS 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Azerbaijan 167/180* Eritrea 180/180* Isaias AFWERKI Ilham Aliyev Born 2 February 1946 Born 24 December 1961 > President of the Republic of Eritrea > President of the Republic of Azerbaijan since 19 May 1993 since 2003 > Predator since 18 September 2001, the day he suddenly eliminated > Predator since taking office, but especially since 2014 his political rivals, closed all privately-owned media and jailed outspoken PREDATORY METHOD: Subservient judicial system journalists Azerbaijan’s subservient judicial system convicts journalists on absurd, spurious PREDATORY METHOD: Paranoid totalitarianism charges that are sometimes very serious, while the security services never The least attempt to question or challenge the regime is regarded as a threat to rush to investigate physical attacks on journalists and sometimes protect their “national security.” There are no more privately-owned media, only state media assailants, even when they have committed appalling crimes. Under President with Stalinist editorial policies. Journalists are regarded as enemies. Some have Aliyev, news sites can be legally blocked if they pose a “danger to the state died in prison, others have been imprisoned for the past 20 years in the most or society.” Censorship was stepped up during the war with neighbouring appalling conditions, without access to their family or a lawyer. According to Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and the government routinely refuses to give the information RSF has been getting for the past two decades, journalists accreditation to foreign journalists. -

Global Peace Index 2018: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2018

Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City and Brussels. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Peace Index 2018: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2018. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings 4 RESULTS 5 Highlights 6 2018 Global Peace Index rankings 8 Regional overview 12 Improvements & deteriorations 19 TRENDS 23 Ten year trends in the Global Peace Index 26 100 year trends in peace 32 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF VIOLENCE 45 Results 46 The macroeconomic impact of peace 52 POSITIVE PEACE 59 What is Positive Peace? 60 Trends in Positive Peace 65 What precedes a change in peacefulness? 69 Positive Peace and the economy 73 APPENDICES 77 Appendix A: GPI Methodology 78 Appendix B: GPI indicator sources, definitions & scoring criteria 82 Appendix C: GPI Domain scores 90 Appendix D: Economic cost of violence 93 GLOBAL PEACE INDEX 2018 | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the twelfth edition of the Global Peace Index Afghanistan, South Sudan, Iraq, and Somalia comprise (GPI), which ranks 163 independent states and the remaining least peaceful countries. -

Korean Communication and Mass Media Research

International Journal of Communication 2 (2008), 253-275 1932-8036/20080253 Korean Communication and Mass Media Research: Negotiating the West’s Influence JUKKA PEKKA JOUHKI University of Jyväskylä The purpose of this article is to introduce and discuss Korean communication with an emphasis on mass media research in the context of globalization. The American influence on this discipline will be focused on, and the current discussion between indigenization and globalization will be introduced. Lastly, some weak and strong signals for the future of the discipline will be proposed. The main sources are major Korean journals related to the theme in the last few years. References to journals and other publications are deliberately frequent to help the reader find more information on specific themes of research. Moreover, the introduction of the Korean media cultural context has been emphasized due to its unfamiliarity in the global forum. This article is a part of a research project (2006-2009) examining Korean media and new media culture, and it has been funded by the Helsingin Sanomat Foundation1. Korean Mediascape Korea2 is one of the greatest economic success stories of Asia. Throughout its geopolitical history, the Korean Peninsula has been affected by the Japanese, Chinese, and Americans, as well as, recently, by the accelerating forces of globalization — all of them giving great impetus and delicate nuance to Korean society and culture. The Chinese sociocultural effect on Korea has been most significant in terms of its temporality, but also the effect of the Japanese, especially during the Japanese occupation (1910-1945) has been immense, influencing, for example, the Korean education system and the work culture. -

Media Discourses on the Other: Japanese History Textbook Controversies in Korea

Media Discourses on the Other: Japanese History Textbook Controversies in Korea Dong-Hoo Lee University of Incheon, Korea [email protected] One of roles of the mass media has been to record, interpret, and reinterpret important moments in national history, thus helping to form what has been called people’s “collective memories.” When history is viewed as a struggle to retain memory, the popular text that carries and recollects the past of a nation-state is not merely mass-delivering factual information about the past; it is reconstructing the concurrent meanings of the past and determining the direction of historical perception. The media of communication condition the form and content of memory and provide a place for historical discourses that compete with that memory. For people in Korea, which was under Japanese colonial rule between 1910 and 1945, their thirty-six year experience of the Japanese as colonialists has been an unsettled diplomatic issue. This painful experience has also consciously and unconsciously affected the Korean media’s construction of images of Japan. While Japan assumes that the Korea–Japan pact of 1965 has resolved the issue of legal indemnity, many Koreans believe that Japan’s reflection on the past has not been sincere enough to eradicate their internalized feeling of being victims of Japanese imperialism. The official apologies made by Japanese leaders have been viewed as formal statements that were not followed by any efforts to liquidate the colonial past. The periodic statements made by leading Japanese politicians that gloss over the colonial past and Japanese textbooks that represent a past that is detached from Koreans’ experiences have aroused anti- Japanese feeling to the present day. -

Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #1086

Issue No. 1086, 18 October 2013 Articles & Other Documents: Featured Article: U.S. Nuclear Arms Modernization Plan Misguided: Scientists' Group 1. IRGC Rejects Report on Maximum Range of Iranian Missiles 2. Iran to Offer 3-Stage Proposal in Geneva Nuclear Talks 3. Negotiator: Taking Iran's Uranium Stockpile Out "Iran's Redline" 4. Iran Plans New Monkey Space Launch 5. 'Netanyahu is Not Bluffing on Intention to Strike Iran' 6. Ayatollah Khamenei's Aide: Americans No Trustworthy Partner for Talks 7. Kerry Says Diplomatic Window with Iran is ‘Cracking Open’ 8. Oman Calls for a Nuclear-Free Middle East 9. Assad: Loss of Chemical Weapons is Blow to Syria's Morale, Political Standing 10. Gallup Poll: Iranians Divided on Nuclear Weapons 11. Chemical Watchdog says has Verified 11 Syria Sites 12. Iran, World Powers Pledge New Nuclear Talks 13. Saudi Arabia Declines UN Security Council Seat 14. North Korea Rejects U.S. Offer of Non-Aggression Agreement, Wants Sanctions Halted 15. North Korea Warns of 'All-Out War' 16. N. Korea Ready to Make another Nuke Test Anytime: S. Korean Envoy 17. S. Korea Seeks Multi-Layered Missile Defense against North 18. North Korea Replaced General Linked to Cuban Weapons Shipment 19. Defense Chief Denies U.S.-Led Missile Defense Participation 20. N. Korea Must Break 'Illusion' of Nuclear Status: China Expert 21. Refitted Aircraft Carrier to Leave for India November 30 – Deputy Premier 22. Inside the Ring: Russia to Test New Missile 23. US Lab in Georgia at Center of Storm Over Biological Warfare Claims 24. A Real Nuclear Deterrent: US, Russia may Team Up to Use Weapons against Asteroids 25. -

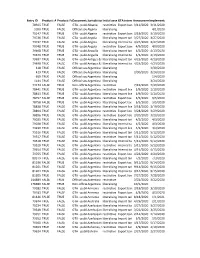

Chan GTA Intervention Type

Entry ID Product: AnyProduct: medical Food productDocumentationJurisdiction statusInitial assessmentGTA intervention (changeAnnouncement relative type Implementation to 1date Jan 2020) date 78925 TRUE FALSE GTA - publishedAlbania restrictive Export ban 3/11/2020 3/11/2020 1090 TRUE FALSE Official sourceAlgeria liberalising 4/1/2020 79147 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedAlgeria restrictive Export ban 3/19/2020 3/19/2020 79726 TRUE FALSE GTA - publishedAngola liberalising Import tariff3/27/2020 3/27/2020 79727 TRUE FALSE GTA - publishedAngola liberalising Internal taxation3/27/2020 of imports3/27/2020 79748 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedAngola restrictive Export ban 4/9/2020 4/9/2020 79668 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedAnguilla liberalising Import tariff 4/2/2020 4/13/2020 79670 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedAnguilla liberalising Internal taxation4/2/2020 of imports4/13/2020 79697 TRUE FALSE GTA - publishedAntigua & Barbudaliberalising Import tariff4/23/2020 4/23/2020 79698 TRUE FALSE GTA - publishedAntigua & Barbudaliberalising Internal taxation4/23/2020 of imports4/23/2020 418 TRUE FALSE Official sourceArgentina liberalising 3/30/2020 419 TRUE FALSE Official sourceArgentina liberalising 3/30/2020 3/24/2020 659 TRUE FALSE Official sourceArgentina liberalising 1/4/2020 1144 TRUE FALSE Official sourceArgentina liberalising 3/24/2020 74173 FALSE TRUE Non-officialArgentina source restrictive 7/19/2020 7/20/2020 78441 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedArgentina restrictive Import licensing1/9/2020 requirement1/10/2020 78443 TRUE TRUE GTA - publishedArgentina liberalising