Connexe 4 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

A Comparative Constitutional Analysis Between Italy and Hungary

Department of Political Science Master’s Degree in International Relations – European Studies Chair in Comparative Public Law POPULISM IN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE EUROPEAN UNION: A COMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS BETWEEN ITALY AND HUNGARY SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Professor Cristina Fasone Claudia Mattei 635892 CO-SUPERVISOR Professor Giovanni Orsina Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Table of contents Introduction 6 1 CHAPTER – POPULISM 9 1.1 What is populism? A definition for a highly contested phenomenon 10 1.2 Understanding populism 14 1.2.1 Who are the people? 14 1.2.2 Who are the elites? 18 1.2.3 The real meaning of the volonté générale 19 1.2.4 The people and the general will: populism vs. democracy 20 1.3 Historical birth of populism 24 1.3.1 The American People’s Party 24 1.3.2 The Russian narodnichestvo 26 1.4 Marriage between populism and ‘host’ ideologies: different families 29 1.4.1 Right-wing populism 30 1.4.2 Left-wing populism 31 1.4.3 Populist constitutionalism 33 1.5 Why does populism develop? 36 1.5.1 The causes behind the populist rise 37 1.5.2 The cause of the cause: the auto-destruction of politics as origin of populism 39 1.5.3 Technocracy replaces politics: the case of the European Union 41 1.6 Populism in the world 44 2 CHAPTER – POPULISM IN EUROPE 48 2.1 Genesis of populism in Europe: Boulangism 48 2.2 Populism in Western Europe 51 2.2.1 Post-WW2 populist experiences in Western Europe 51 2.2.2 The rise of modern populism in Western Europe 53 2 2.3 Populism in Eastern Europe 58 2.3.1 Interwar populism in Eastern Europe 58 2.3.2 -

Agrarian Theory and Policy in Bulgaria from 1919-1923

New Nation, New Nationalism: Agrarian Theory and Policy in Bulgaria from 1919-1923 By Eric D. Halsey Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Michael Laurence Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2012 Abstract There exists a critical gap in the literature between analysis of the regime of Alexander Stamboliski from a basic historical perspective and a broader ideological perspective rooted in nationalism theory. The result of this gap has been a division of research between those who look simply at the policies of the regime and those who attempt to discuss it in a framework of what is almost always Marxist ideology. By examining the policies and historical context of the Stamboliski regime in conjunction with analyzing it through the lens of nationalism theory, the depth and importance of the regime become clearer. Through this framework it becomes possible to view what is often called an anti-national regime as a nationalist regime attempting to re-forge the national identities of Bulgaria and, eventually, the entire Balkans. This comes with implications in how we view nationalism in the Balkans, Agrarianism, and the broader processes of addressing modernization and the region's Ottoman legacy. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my mother for all of her love and support through all of my travels, studies, and research. It can't be easy to see a son rush off into something so unknown to you. I would also like to thank my academic advisor from my undergraduate university Professor Nabil Al-Tikriti for his support, advice, and useful commentary through the past several years. -

R01545 0.Pdf

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 2 Tab Number: 10 Document Title: The 1990 Bulgarian Elections: A Pre-Election Assessment, May 1990 Document Date: 1990 Document Country: Bulgaria IFES ID: R01545 ~" I •••··:"_:5 .~ International Foundation fo, Electo,al Systems I --------------------------~---------------- ~ 1101 15th STREET. NW·THIRD FLOOR· WASHINGTON. D.C. 20005·12021 828-8507·FAX 12021 452-0804 I I I I I THE 1990 BULGARIAN ELECTIONS: A PRE-ELECTION ASSESSMENT I I MAY 1990 I I Team Members Dr. John Bell Mr. Ronald A. Gould I Dr. Richard G. Smolka I I I I This report was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy. Any person or organization is welcome to quote information from this report if it is attributed to IFES. I 8CWlD OF DIREQORS Barbara Boggs Maureen A. Kindel WilHam R. Sweeney. Jr. Randal C. Teague Counsel Charles T. Manatt Patricia Hutar Frank 1. Fahrenkopf Jr. Jean-Pierre Kingsley leon). Weir I Chairman SecretaI)' Judy Fernald Peter M(Pher~On DIREQORS EMERITI Richard W. Soudricne David R. Jones Joseph Napolitan James M. Cannon Director I Vice Chairman Treasurer Victor Kamber Sonia Picado S. Richard M Scammon I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I ii I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Part I. overview I Mission 3 Executive Summary 4 I The Historical context 6 I Current Political Scene 13 I Part II. Election Law and procedures Constitutional and Legal Foundations of Electoral Law 20 I The Law on Political Parties The Election Act I Analysis of the Law I The Electoral system 30 structure and Procedures I Comments and Analysis I Electoral Needs 38 I Team Recommendations 41 I I Appendices A. -

The Image of Turkey in the Public Discourse of Interwar Yugoslavia During the Reign of King Aleksandar Karađorđević (1921–1934) According to the Newspaper “Politika”

ZESZYTY NAUKOWE TOWARZYSTWA DOKTORANTÓW UJ NAUKI S , NR 24 (1/2019), S. 143–166 E-ISSN 2082-9213 | P-ISSN 2299-2383 POŁECZNE WWW. .UJ.EDU.PL/ZESZYTY/NAUKI- DOI: 10.26361/ZNTDSP.10.2019.24.8 DOKTORANCI SPOLECZNE HTTPS:// .ORG/0000-0002-3183-0512 ORCID P M ADAM M AWEŁUNIVERSITYICHALAK IN P F HISTORY ICKIEWICZ OZNAŃ E-MAIL: PAWELMALDINI@ .ONET.PL ACULTY OF POCZTA SUBMISSION: 14.05.2019 A : 29.08.2019 ______________________________________________________________________________________CCEPTANCE The Image of Turkey in the Public Discourse of Interwar Yugoslavia During the Reign of King Aleksandar Karađorđević (1921–1934) According to the Newspaper “Politika” A BSTRACT Bearing in mind the Ottoman burden in relations between Turkey and other Balkan states, it seems interesting to look at the process of creating the image of Turkey in the public discourse of inter-war Yugoslavia according to the newspaper “Politika,” the largest, and the most popular newspaper in the Kingdom of d Slovenes (since 1929 the Kingdom of Yugoslavia). It should be remembered that the modern Ser- bian state, on the basis of which Yugoslavia was founded, wasSerbs, born Croats in the an struggle to shed Turkish yoke. The narrative about dropping this yoke has become one of the On the one hand, the government narrative did not forget about the Ottoman yoke; oncornerstones the other, therefor building were made the prestige attempts and to thepresent position Kemalist of the Turkey Karađorđević as a potentially dynasty. important partner, almost an ally in the Balkans, -

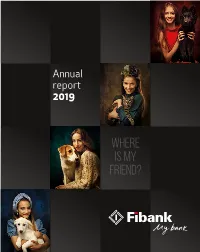

Where Is My Friend?

Annual report 2019 Where is my friend? WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e Fibank Supports the Bulgarian Rhythmic Gymnastics Federation and the Animal Rescue Sofia pet shelter Cover (top to bottom): Margarita Vasileva – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and dog Stella from Animal Rescue pet shelter Nevyana Vladinova – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and cat Zory from Animal Rescue pet shelter Simona Dyankova – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team аnd dog Buddy from Animal Rescue pet shelter Catherine Tsoneva – member of the Bulgarian National Rhythmic Gymnastics team and dog Belcho from Animal Rescue pet shelter WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e With the rapid development of digitalization, technology and globalization, it is ever more important to preserve our human nature, spirituality and empathy. In this year’s report, along with our financial and corporate results, we tried to give a visual expression of that inner light that inspires us and makes us better and happier persons. Where is my Friend is not just a question, but also a matter of choice. The team of WorldReginfo - 6d7d956a-d08e-4406-874f-a3df3fd8a00e The present report is prepared on the grounds of and in compliance with the requirements of the Accounting Act, the Law on Public Offering of Securities, Ordinance №2 of the Financial Supervision Commission for the prospects of public offering and admittance for trade on a regulated market of securities and for the disclosure of information, Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms and the National Corporate Governance Code, approved by the Financial Supervision Commission. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2013

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set, 1960-2013 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET 1960-2013 Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2013 (CPDS) is a collection of political and institu- tional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Hand- lungsspielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” directed by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member coun- tries for the period of 1960 to 2013. In all countries, political data were collected only for the democratic periods.1 The data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time- series analyses. The present data set combines and replaces the earlier versions “Comparative Political Data Set I” (data for 23 OECD countries from 1960 onwards) and the “Comparative Political Data Set III” (data for 36 OECD and/or EU member states from 1990 onwards). A variable has been added to identify former CPDS I countries. For additional detailed information on the composition of government in the 36 countries, please consult the “Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Com- position 1960-2013”, available on the CPDS website. The Comparative Political Data Set contains some additional demographic, socio- and eco- nomic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD, Eurostat or AMECO. -

Collaborative

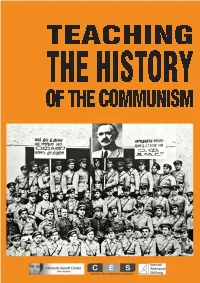

TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Published by: Hannah Arendt Center – Sofia 2013 This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center - Sofia and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. The Centre for European Studies, the Hannah Arendt Center -Sofia, the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or any subsequent use of the information contained therein. Sole responsibility lies on the author of the publication. The processing of the publication was concluded in 2013 The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP) dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu TEACHING THE HISTORY OF THE COMMUNISM Editor: Vasil Kadrinov Print: AVTOPRINT www.avtoprint.com E-mail: [email protected] Phohe: +359 889 032 954 2 Kiril Hristov Str., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria Teaching the History of the Communism Content Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe - Methodological and Sensitive Issues, Raluca Grosescu ..................5 National representative survey on the project: “Education about the communist regime and the european democratic values of the young people in Bulgaria today”, 2013 .......................................................14 Distribution of the data of the survey ...........................................................43 - 3 - Teaching the History of the Communism Teaching the History of the Communist Regimes in Post-1989 Eastern Europe Methodological and Sensitive Issues Raluca Grosescu The breakdown of dictatorial regimes generally implies a process of rewriting history through school curricula and textbooks. -

Notices from Member States

C 248/4EN Official Journal of the European Union 30.9.2008 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES First processing undertakings in the raw tobacco sector approved by the Member States (2008/C 248/05) This list is published under Article 171co of Commission Regulation (EC) No 1973/2004 of 29 October 2004 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 1782/2003 as regards the tobacco aid scheme. BELGIUM „Topolovgrad — BT“ AD Street „Hristo Botev“ 10 MANIL V. BG-8760 Topolovgrad Rue du Tambour 2 B-6838 Corbion „Bulgartabak Holding“ AD TABACS COUVERT Street „Graf Ignatiev“ 62 Rue des Abattis 49 BG-1000 Sofia B-6838 Corbion „Pleven — BT“ AD TABAC MARTIN Sq. „Republika“ 1 Rue de France 176 BG-5800 Pleven B-5550 Bohan BELFEPAC nv „Plovdiv — BT“ AD R.Klingstraat, 110 Street „Avksentiy Veleshki“ 23 B-8940 Wervik BG-4000 Plovdiv VEYS TABAK nv „Gotse Delchev — Tabak“ AD Repetstraat, 110 Street „Tsaritsa Yoana“ 12 B-8940 Wervik BG-2900 Gotse Delchev MASQUELIN J. „ — “ Wahistraat, 146 Dulovo BT AD „ “ B-8930 Menen Zona Sever No 1 BG-7650 Dulovo VANDERCRUYSSEN P. Kaaistraat, 6 „Dupnitsa — Tabak“ AD B-9800 Deinze Street „Yahinsko Shose“ 1 BG-2600 Dupnitsa NOLLET bvba Lagestraat, 9 „Kardzhali — Tabak“ AD B-8610 Wevelgem Street „Republikanska“ 1 BG-6600 Kardzhali BULGARIA „ — “ (BT = Bulgarian tobacco; AD = joint stock company; Pazardzhik BT AD „ “ VK = universal cooperative; ZPK = Insurance and Reinsurance Street Dr. Nikola Lambrev 24 Company; EOOD = single-person limited liability company; BG-4400 Pazardzhik ET = sole trader; OOD = limited liability company) „Parvomay — BT“ AD „Asenovgrad — Tabak“ AD Street „Omurtag“ 1 Street „Aleksandar Stamboliyski“ 22 BG-4270 Parvomay BG-4230 Asenovgrad „ “ „Sandanski — BT“ AD Blagoevgrad BT AD „ “ Street Pokrovnishko Shosse 1 Street Svoboda 38 BG-2700 Blagoevgrad BG-2800 Sandanski „Missirian Bulgaria“ AD „Smolyan Tabak“ AD Blvd. -

The Latvian Agrarian Union and Agrarian Reform Between the Two

TITLE: RIDING THE TIGER : THE LATVIAN AGRARIAN UNION AN D AGRAIAN REFORM BETWEEN THE TWO WORLD WAR S AUTHOR: ANDREJS PLAKANS, Iowa State University THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION : ' CONTRACTOR : Iowa State University PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Andrejs Plakans and Charles Wetherel l COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 810-23 DATE : December 31, 199 6 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded by Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written report s and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within th e Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials fo r their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, or make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without the written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom o f Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law . The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Councilfor Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). The analysis an d interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s) . -

Viktor Milanov Direct Democracy in Bulgaria

Pázmány Law Working Papers 2016/1 Viktor Milanov Direct Democracy in Bulgaria Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem Pázmány Péter Catholic University Budapest http://www.plwp.jak.ppke.hu/ DIRECT DEMOCRACY IN BULGARIA* ** VIKTOR MILANOV 1. Historic antecedents 1.1.The referendum of 1922. Prior to the fall of the communist regime in Bulgaria referendums were held only three times in the history of the Balkan country. Almost five years after the end of World War I the government led by Aleksandar Stamboliyski legislated a new Criminal Law with retroactive effect which allowed the conviction of members of former governments involved in the Balkan Wars and the World War as well. Stamboliyski sought a way to discredit members of the Geshov-, Danev-, Malinov- and Kosturkov-governments who by that time were his main political rivals.1 In order to gain broader social acceptance to execute these controversial political trials, the Bulgarian government held a nationwide referendum on 19th of November 1922 with the question whether or not to convict those who were responsible for the national catastrophes. The Bulgarian Agrarian National Union based government led a successful campaign among the voters and results of the referendum were more than satisfying for the Stamboliyski cabinet, more than 74 % of the voters cast their votes for the conviction of the former ministers. The total number of the voters was 926 000; 647 000 voted for, while 224 000 voted against the conviction. 55 000 ballots were invalid.2 The referendum was based on the “Law on Referendum of the Liability of the Ministers of the Geshov-, Danev-, Malinov- and Kosturkov-governments for the wars they led and the national catastrophes which occurred afterwards” adopted by the XIX. -

Codebook CPDS III 1990-2012

Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET III 1990-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for a group of 36 OECD and/or EU- member countries for the period 1990-20121. The data are primarily from the data set created at the University of Berne, Institute of Political Science and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation: The Comparative Political Data Set I (CPDS I). However, the present data set differs in several aspects from the CPDS I dataset. Compared to CPDS I Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus (Greek part), Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have been added. The present data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions is provided by Jelle Visser (2013). When using the data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. This data set is to be cited as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. 2014. Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2014-09-30 1 Data for former communist countries begin in 1990 for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Lativa and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia.