Lesetja Kganyago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors

THE WORLD BANK GROUP Public Disclosure Authorized 2016 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS Public Disclosure Authorized SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Public Disclosure Authorized Washington, D.C. October 7-9, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK GROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. Phone: (202) 473-1000 Fax: (202) 477-6391 Internet: www.worldbankgroup.org iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group (Bank), which consist of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), held jointly with the International Monetary Fund (Fund), took place on October 7, 2016 in Washington, D.C. The Honorable Mauricio Cárdenas, Governor of the Bank and Fund for Colombia, served as the Chairman. In Committee Meetings and the Plenary Session, a joint session with the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund, the Board considered and took action on reports and recommendations submitted by the Executive Directors, and on matters raised during the Meeting. These proceedings outline the work of the 70th Annual Meeting and the final decisions taken by the Board of Governors. They record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors and the resolutions and reports adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. In addition, the Development Committee discussed the Forward Look – A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030, and the Dynamic Formula – Report to Governors Annual Meetings 2016. -

Global Finance's Central Banker Report Cards 2021

Global Finance’s Central Banker Report Cards 2021 NEW YORK, September 1, 2021 — Global Finance magazine has released the names of Central Bank Governors who earned “A” or “A-” grades as part of its Central Banker Report Cards 2021. The full Central Banker Report Cards 2021 report and grade list will appear in Global Finance’s October print and digital editions and online at GFMag.com. The Central Banker Report Cards, published annually by Global Finance since 1994, grade the central bank governors of 101 key countries and territories including the European Union, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, the Bank of Central African States and the Central Bank of West African States. About Global Finance Grades are based on an “A” to “F” scale for success in areas such as inflation control, economic Global Finance, founded in growth goals, currency stability and interest rate management. (“A” represents an excellent 1987, has a circulation of performance down through “F” for outright failure.) Subjective criteria also apply. 50,000 and readers in 191 countries. Global Finance’s “With the pandemic still surging in many areas, and inflation emerging as a major area of audience includes senior concern once again, the world’s central bankers are confronting multiple challenges from corporate and financial multiple directions,” said Global Finance publisher and editorial director Joseph Giarraputo. officers responsible for making investment and strategic “Global Finance’s annual Central Banker Report Cards show which financial policy leaders are decisions at multinational succeeding in the face of adversity and which are falling behind.” companies and financial The Central Bankers earning an “A” grade in the Global Finance Central Banker Report Card institutions. -

Local Currency Bond Markets Conference South African Reserve Bank (SARB) Conference Centre, Pretoria, South Africa

Local Currency Bond Markets Conference South African Reserve Bank (SARB) Conference Centre, Pretoria, South Africa Thursday, 8 March 2018 Venue: SARB Conference Centre Auditorium 11.00 – 12.00 Registration 12.00 – 13.00 Finger lunch Programme Director: Mr Nimrod Lidovho, SARB 13.00 – 13.15 Welcome address by Governor Lesetja Kganyago, SARB 13.15 – 13.45 Opening remarks "Facing up to the original sin - The German experience of establishing a local currency bond market" by Andreas Dombret, Board Member, Deutsche Bundesbank 13.45 – 14.30 Keynote “Local currency markets – the case of a development bank” Joachim Nagel, Member of the Executive Board, KfW 14.30 – 14.45 Coffee break 14.45 – 15.30 “African growth and prosperity: the important role of local currency bond markets” by Stacie Warden, Executive Director, Center for Financial Markets, Milken Institute 15.30 – 16.15 Expert speech “Challenges of development of LCBM in emerging markets” Leon Myburgh, SARB 16.15 – 17.15 Bilateral talk “CWA: Development of financial markets in Africa” moderated by Deputy Governor Daniel Mminele, SARB Dondo Mogajane and Ludger Schuknecht, co-chairs of G-20 Africa Advisory Group, ZAF/GER Venue: SARB Conference Centre Banqueting Room 18.00 – 21.00 Conference dinner 18.00 – 18.20 Dinner remarks by Deputy Governor Daniel Mminele, SARB Friday, 9 March 2018 Venue: SARB Conference Centre Auditorium Programme Director: Mr Martin Dinkelborg, Deutsche Bundesbank 9.00 – 10.30 Panel discussion “The role of central banks in establishing primary markets” moderated by Zafar -

The Group of Twenty: a History

THE GROUP OF TWENTY : A H ISTORY The study of the G-20’s History is revealing. A new institution established less than 10 years ago has emerged as a central player in the global financial architecture and an effective contributor to global economic and financial stability. While some operational challenges persist, as is typical of any new institution, the lessons from the study of the contribution of the G-20 to global economic and financial stability are important. Because of the work of the G-20 we are already witnessing evidence of the benefits of shifting to a new model of multilateral engagement. Excerpt from the closing address of President Mbeki of South Africa to G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 18 November 2007, Kleinmond, Western Cape. 2 Table of Contents Excerpt from a Speech by President Mbeki....................................................................2 Executive Summary...........................................................................................................5 The Group of Twenty: a History ......................................................................................7 Preface............................................................................................................................7 Background....................................................................................................................8 The G-22 .............................................................................................................12 The G-33 .............................................................................................................15 -

8-11 July 2021 Venice - Italy

3RD G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETING AND SIDE EVENTS 8-11 July 2021 Venice - Italy 1 CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THE G20 Pag. 3 2 ITALIAN G20 PRESIDENCY Pag. 4 3 2021 G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETINGS Pag. 4 4 3RD G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETING Pag. 6 Agenda Participants 5 MEDIA Pag. 13 Accreditation Media opportunities Media centre - Map - Operating hours - Facilities and services - Media liaison officers - Information technology - Interview rooms - Host broadcaster and photographer - Venue access Host city: Venice Reach and move in Venice - Airport - Trains - Public transports - Taxi Accomodation Climate & time zone Accessibility, special requirements and emergency phone numbers 6 COVID-19 PROCEDURE Pag. 26 7 CONTACTS Pag. 26 2 1 ABOUT THE G20 Population Economy Trade 60% of the world population 80 of global GDP 75% of global exports The G20 is the international forum How the G20 works that brings together the world’s major The G20 does not have a permanent economies. Its members account for more secretariat: its agenda and activities are than 80% of world GDP, 75% of global trade established by the rotating Presidencies, in and 60% of the population of the planet. cooperation with the membership. The forum has met every year since 1999 A “Troika”, represented by the country that and includes, since 2008, a yearly Summit, holds the Presidency, its predecessor and with the participation of the respective its successor, works to ensure continuity Heads of State and Government. within the G20. The Troika countries are currently Saudi Arabia, Italy and Indonesia. -

World Economic Forum on Africa

World Economic Forum on Africa List of Participants As of 7 April 2014 Cape Town, South Africa, 8-10 May 2013 Jon Aarons Senior Managing Director FTI Consulting United Kingdom Muhammad Programme Manager Center for Democracy and Egypt Abdelrehem Social Peace Studies Khalid Abdulla Chief Executive Officer Sekunjalo Investments Ltd South Africa Asanga Executive Director Lakshman Kadirgamar Sri Lanka Abeyagoonasekera Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies Mahmoud Aboud Capacity Development Coordinator, Frontline Maternal and Child Health Empowerment Project, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Sudan Fatima Haram Acyl Commissioner for Trade and Industry, African Union, Addis Ababa Jean-Paul Adam Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Seychelles Tawia Esi Director, Ghana Legal Affairs Newmont Ghana Gold Ltd Ghana Addo-Ashong Adekeye Adebajo Executive Director The Centre for Conflict South Africa Resolution Akinwumi Ayodeji Minister of Agriculture and Rural Adesina Development of Nigeria Tosin Adewuyi Managing Director and Senior Country JPMorgan Nigeria Officer, Nigeria Olufemi Adeyemo Group Chief Financial Officer Oando Plc Nigeria Olusegun Aganga Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment of Nigeria Vikram Agarwal Vice-President, Procurement Unilever Singapore Anant Agarwal President edX USA Pascal K. Agboyibor Managing Partner Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe France Aigboje Managing Director Access Bank Plc Nigeria Aig-Imoukhuede Wadia Ait Hamza Manager, Public Affairs Rabat School of Governance Morocco & Economics -

The Daily Brief

The Daily Brief Market Update Friday, 22 January 2021 SARB on Hold South Africa's central bank kept its main lending rate at 3.5% on Thursday, saying overall risks to the inflation outlook appeared to be balanced in the near and medium term. Three members of the monetary policy committee wanted to hold the repo rate and two preferred a 25 basis point cut, Governor Lesetja Kganyago said. The decision was in line with a Reuters poll published last week. "The committee notes that the slow economic recovery will help keep inflation below the midpoint of the target range for this year and next," Kganyago added, referring to the bank's 3% to 6% target range. The South African Reserve Bank cut interest rates by a cumulative 300 basis points last year to cushion the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inflation in Africa's most industrialised economy has been benign, giving the bank space to be accommodative. "Monetary policy has eased financial conditions and improved the resilience of households and firms to the economic implications of COVID-19," Kganyago said. "Economic and financial conditions are expected to remain volatile for the foreseeable future. In this highly uncertain environment, policy decisions will continue to be data dependent and sensitive to the balance of risks to the outlook." Global Markets Asian shares eased from record highs on Friday as investors took some money off the table after a recent rally that was driven by hopes a massive U.S. economic stimulus plan by incoming President Joe Biden will help temper the COVID-19 impact. -

Meeting of the Financial Stability Board Regional Consultative Group for Sub-Saharan Africa

Press enquiries: Press release +41 76 350 8024 [email protected] Ref no: 12/2012 3 February 2012 Meeting of the Financial Stability Board Regional Consultative Group for Sub-Saharan Africa Today, the South African Reserve Bank hosted the inaugural meeting of the FSB Regional Consultative Group (RCG) for Sub-Saharan Africa in Pretoria. The group was established pursuant to the FSB’s announcement in November 2010 that it intends to expand and formalise outreach beyond its membership. To this end, six regional consultative groups1 were established to bring together financial authorities from FSB member and non-member countries to exchange views on vulnerabilities affecting financial systems and on initiatives to promote financial stability. At their meeting today, RCG for Sub-Saharan Africa members discussed the FSB’s work plan and policy priorities, major financial regulatory reforms and their impacts, as well as vulnerabilities and regional financial stability issues. Discussions on regulatory reforms and their impacts centred around implementation of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision2, capital standards for financial institutions, and improving disclosure and transparency in the financial sector. Under the vulnerabilities and regional financial stability issues heading, members discussed the vulnerabilities in the euro area and the potential contagion, spillover risks and possible policy responses, as well as policy options for reducing the volatility of capital inflows and the development of domestic capital markets. The Sub-Saharan African region has particular characteristics as well as challenges that will form the basis of the future work plan of the RCG for Sub-Saharan Africa and more broadly, policy solutions for the region. -

BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4Th Industrial Revolution

BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4th Industrial Revolution SANDTON CONVENTION CENTRE JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA 25 TO 27 JULY 2018 10TH BRICS SUMMIT JOHANNESBURG DECLARATION I. PREAMBLE 1. We, the Heads of State and Government of the Federative Republic of Brazil, the Russian Federation, the Republic of India, the People's Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa, met from 25 - 27 July 2018 in Johannesburg, at the 10th BRICS Summit. The 10th BRICS Summit, as a milestone in the history of BRICS, was held under the theme “BRICS in Africa: Collaboration for Inclusive Growth and Shared Prosperity in the 4th Industrial Revolution”. 2. We are meeting on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of Nelson Mandela and we recognise his values, principles and dedication to the service of humanity and acknowledge his contribution to the struggle for democracy internationally and the promotion of the culture of peace throughout the world. 3. We commend South Africa for the Johannesburg Summit thrust on development, inclusivity and mutual prosperity in the context of technology driven industrialisation and growth. 4. We, the Heads of State and Government, express satisfaction regarding the achievements of BRICS over the last ten years as a strong demonstration of BRICS cooperation toward the attainment of peace, harmony and shared development and prosperity, and deliberated on ways to consolidate them further. 1 5. We reaffirm our commitment to the principles of mutual respect, sovereign equality, democracy, inclusiveness and strengthened collaboration. As we build upon the successive BRICS Summits, we further commit ourselves to enhancing our strategic partnership for the benefit of our people through the promotion of peace, a fairer international order, sustainable development and inclusive growth, and to strengthening the three-pillar-driven cooperation in the areas of economy, peace and security and people-to-people exchanges. -

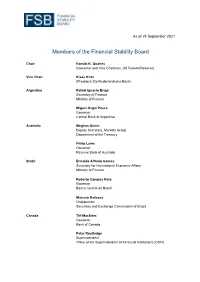

Members List FSB Plenary

As of 24 September 2021 Members of the Financial Stability Board Chair Randal K. Quarles (Governor and Vice Chairman, US Federal Reserve) Vice Chair Klaas Knot (President, De Nederlandsche Bank) Argentina Rafael Ignacio Brigo Secretary of Finance Ministry of Finance Miguel Ángel Pesce Governor Central Bank of Argentina Australia Meghan Quinn Deputy Secretary, Markets Group Department of the Treasury Philip Lowe Governor Reserve Bank of Australia Brazil Erivaldo Alfredo Gomes Secretary for International Economic Affairs Ministry of Finance Roberto Campos Neto Governor Banco Central do Brasil Marcelo Barbosa Chairperson Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil Canada Tiff Macklem Governor Bank of Canada Peter Routledge Superintendent Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) Canada Nick Leswick Associate Deputy Minister Department of Finance China Zou Jiayi Vice Minister Ministry of Finance Yi Gang Governor People’s Bank of China Guo Shuqing Chairman China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission France François Villeroy de Galhau Governor Banque de France Emmanuel Moulin Director General, Treasury and Economic Policy Directorate Ministry of Economy and Finance Robert Ophèle Chairman Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) Germany Jörg Kukies State Secretary Federal Ministry of Finance Jens Weidmann President Deutsche Bundesbank Mark Branson President Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) Hong Kong Eddie Yue Chief Executive Hong Kong Monetary Authority India Ajay Seth Secretary, Economic Affairs -

Private Sector Development in Africa

VISUAL SUMMARY INNOVATIVE FINANCE FOR PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA ECONOMIC REPORT ON AFRICA 2020 VISUAL SUMMARY INNOVATIVE FINANCE FOR PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA ECONOMIC REPORT ON AFRICA 2020 VisualVisual SummarySummary INNOVATIVEINNOVATIVE FINANCEFINANCE FORFOR PRIVATEPRIVATE SECTORSECTOR DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT ININ AFRICAAFRICA ECONOMICECONOMIC REPORTREPORT ONON AFRICAAFRICA 20202020 Ordering information To order copies of this report, please contact: Publications Economic Commission for Africa P.O. Box 3001 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tel: +251 11 544-9900 Fax: +251 11 551-4416 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.uneca.org © 2020 United Nations Addis Ababa, Ethiopia All rights reserved First printing December 2020 Title: Economic Report on Africa 2020: Innovative Finance for Private Sector Development in Africa Development in Africa Language: English Sales no.: E.20.II.K.2 ISBN: 978-92-1-125139-5 eISBN: 978-92-1-005124-8 Print ISSN: 2411-8346 eISSN: 2411-8354 Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted. Acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication. The designations employed in this publication and the material presented in it do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Cover design: Carolina Rodriguez, Dilucidar. ii 2020 Economic Report on Africa | INNOVATIVE FINANCE FOR PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA CONTENTS Lists of Figures, Tables and Boxes . v FOREWORD . viii. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . xi ABBREVIATIONS . xiii . EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . .xvi . Recent economic developments . -

Modernising and Transforming the Payments Infrastructure of the Domestic and Regional Settlement Services Division Within the National Payment System Department

Modernising and transforming the payments infrastructure of the Domestic and Regional Settlement Services Division within the National Payment System Department Contents 1. Speakers • Lesetja Kganyago, Governor of the South African Reserve Bank • Tim Masela, Head of the National Payment System Department and Chairperson of the SADC Payment System Subcommittee • Nomwelase Skenjana, Divisional Head of Domestic and Regional Settlement Services 2. Introduction and background 3. Keynote address, Governor Lesetja Kganyago 4. National Payment System Framework and Strategy: Vision 2025, Tim Masela 5. Update on the RTGS programme delivery, Nomwelase Skenjana 6. What’s next? This document is available on the South African Reserve Bank website at www.resbank.co.za 2 © South African Reserve Bank 2021 All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. 1. Speakers Lesetja Kganyago Governor of the South African Reserve Bank Lesetja Kganyago was appointed Governor of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) with effect from 9 November 2014. He was reappointed by the President of South Africa for a second five-year term effective 9 November 2019. Prior to his appointment as Governor, Mr Kganyago served as Deputy Governor of the SARB from 16 May 2011 until his elevation to Governor. Mr Kganyago is the Chairperson of the Monetary Policy Committee and the Financial Stability Committee. He chairs the Committee of Central Bank Governors of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), co-chairs the Financial Stability Board’s Regional Consultative Group for Sub-Saharan Africa, and chairs the Financial Stability Board’s Standing Committee on Standards Implementation. In addition, he served as the Chairperson of the International Monetary and Financial Committee, which is the primary advisory board to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Board of Governors, from 18 January 2018 to 17 January 2021.