Structure, Narrative and Nation in Tourist Performances in Salem, Ma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Tongue to Text: the Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Examination Records

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. From Tongue to Text: The Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Examination Records by Peter Grund 2007 This is the author’s accepted manuscript, post peer-review. The original published version can be found at the link below. Grund, Peter. 2007. “From Tongue to Text: The Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Examination Records.” American Speech 82(2): 119–150. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/00031283-2007-005 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Peter Grund. 2007. “From Tongue to Text: The Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Examination Records.” American Speech 82(2): 119–150. (the accepted manuscript version, post-peer review) From Tongue to Text: The Transmission of the Salem Witchcraft Examination Records1 Peter Grund, Uppsala University Introduction In the absence of audio recordings, scholars interested in studying the characteristics of spoken language in the early Modern period are forced to rely on written speech-related sources.2 These sources include, among others, drama and fiction dialogue, trial proceedings, and witness depositions. However, at the same time, it has been shown that, although purporting to represent spoken conversation, these texts probably reflect actual spoken language only partially and to different degrees (for the evaluation of the degree of “spokenness” of these text categories, see Culpeper and Kytö 2000; see also Kryk-Kastovsky 2000; Moore 2002). Drama and fiction dialogue, for example, represents constructed speech produced by an author who may have been more or less successful in mimicking contemporaneous spoken conversation. -

Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses May 2021 Weaponizing Faith: ‘Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump Paul Hyde Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Hyde, Paul, "Weaponizing Faith: ‘Spectral Evidence’ in Longfellow, Miller and Trump" (2021). All Theses. 3560. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3560 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WEAPONIZING FAITH: “SPECTRAL EVIDENCE” IN LONGFELLOW, MILLER AND TRUMP A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts English by Paul Hyde May 2021 Accepted by: Dr. Michael LeMahieu, Committee Chair Dr. Cameron Bushnell Dr. Jonathan Beecher Field ABSTRACT This thesis explores a particular type of irrational pattern-seeking — specifically, “spectral evidence” — in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Giles Corey of the Salem Farms (1872) and Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953). It concludes with observations of this concept’s continued and concerning presence by other names in Trump-era politics. The two works by Longfellow and Miller make a natural pairing because both are plays inspired by the Salem witchcraft trials (1692-93), a notorious historical miscarriage of justice. Robert Warshow calls the Salem witchcraft trials, aside from slavery, “the most disconcerting single episode in our history: the occurrence of the unthinkable on American soil, and in what our schools have rather successfully taught us to think of as the very ‘cradle of Americanism” (211). -

Salem 1692 Brochure

1 2 3 4 Today Salem, Massachusetts, strives The numbers on the map to be a city of diversity and tolerance, correspond with the sites that but it is important to remember that the appear on the numbered panels. 20 men and women who were executed in All sites except for the Rebecca 1692 were not seeking tolerance. They Nurse Homestead are in Salem. were not witches. They were ordinary men and women seeking justice. 1. Rebecca Nurse Homestead (Danvers, MA) 2. House of the Seven Gables 3. Cemeteries of Salem (3 sites) 4. Salem Witch Trials Memorial Welcome … 5. Salem Witch Hunt: Examine the Evidence to 1692 6. Salem Witch Museum 7. The True 1692 The Rebecca Nurse Homestead The House of the Seven Cemeteries of Salem The Salem Witch Trials 8. Cry Innocent: The People vs. Gables Memorial Bridget Bishop … … … … 9. Witch Dungeon Museum What happened in Salem Town and Salem The Rebecca Nurse Homestead, located in Danvers, The imposing House of the Seven Gables, which has Salem has three cemeteries that are significant to the The Salem Witch Trials Memorial is a place of 10. The Witch House Village (modern-day Danvers) more than MA, (formerly known as Salem Village) is the 17th loomed over Salem Harbor since 1668, remains one of Witch Trials of 1692. Dating back to 1637, Charter meditation, remembrance, and respect for the 20 men 320 years ago still resonates as a measure of century home of Rebecca Nurse, a 71 year old matriarch the oldest surviving timber-framed mansions in North Street Burial Point is the oldest and most visited of and women who were put to death between June and the failure of civility and due process in the who was arrested on suspicion of practicing witchcraft. -

Salem Witch Trial Lesson Plan Grades

History Detectives: Using Historical Inquiry to Teach the Salem Witch Trials in the Elementary Classroom Christopher Martell, Ed.D. Clues (Evidence) from the Salem Witch Trials (Primary source documents were edited for language and ease-of-use with elementary students. Teacher Tip: For 3rd graders, you should help scaffold this activity by adding guiding questions to each primary source – see Clue 7 for an example. Teachers may also reduce amount of text for the lower grades.) CLUE 1: Summary of the Salem Witch Trials from the University of Virginia The Salem witchcraft trials began in late February 1692 and lasted through April 1693. They were held in Salem Village (now Danvers) in Massachusetts Bay Colony. The people of the town believed Samuel Parrisʼ 9 year-old daughter, Elizabeth "Betty" Parris, and her cousin, Abigail Williams, were possessed by the Devil through witchcraft. Betty and Abigail accused the Parrisʼ slave Tituba, (who was from Barbados), of having taught the girls witchcraft. Later, Betty and Abigail also accused Rebecca Nurse, an elderly widow, of spreading witchcraft. The girls, along with their neighbors the Putnums, then accused many in town of being witches. In the end 25 people were convicted: 19 were executed by hanging, 1 was crushed to death under heavy stones, and at least 5 died in jail. Over 160 people across Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of witchcraft and most were jailed. CLUE 2: Testimony (words said at a trial) of Tituba, Samuel Parrisʼ slave from the Caribbean island of Barbados John Hathorne (Judge): What familiarity have you with the Devil? Tituba: The Devil, I am not sure. -

A Quarterly Magazine Devoted to the Biography, Genealogy, History and Antiquities of Essex County, Massachusetts

A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE BIOGRAPHY, GENEALOGY, HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS SIDNEY PERLEY, EDITOR ILLUSTRATED SALEM, MASS. Qbt Qtsse~Bntiqaarfan 1905 CONTENTS. ANswEns, 88, r43; 216, 47; 393, 48; 306, 95; EWETI, MRS. ANN,Will of, 159. 307, 95; 3149 95; 425, 191 ; 4387 191; 44% f EWBTT, JOSEPH,Will of, 113. 143. LAMBERT,FRANCIS, Will of, 36. BANK,T?IS LAND, 135. LAMBERT,JANE, Will of, 67. BAY VIEW CEM~ERY,*GLOUCESTEX, INSCPIP- LAND BANK, The, 135. n0NS IN. 68. LANESVILLB,GWUCBSTBII, INSCRIPTIONS IN BEUY NOTBS,25, 86. OLD CEMETERYAT, 106. B~sco.ELIZABETH, 108. ~THA'SVINEYARD, ESSEX COUNTY MEN AT, BISHOPNOTES, I 13. BEFORE 1700, 134. BLANCHAWGENEAL~GIES, 26, 71. NEW PUBLICATIONS,48,95, 143, 192. BUSY GBNBALOCY,32. NORFOLK COUNTY RECORDS,OW, 137. BLASDIULGENRALOGY, 49. OLDNORFOLK COUNTY RECORDS, 137. B~vmGENSUOGY, I I o. PARRUT,FRANCIS, Will of, 66. BLYTHGENEALOGY, I 12. PEABODY,REV. OLIVER.23. BOARDMAN 145. PBASLEY, JOSEPH,Wd of, 123. ~DwSLLGENMLOOY, 171. PERKINS,JOHN, Will of, 45. BOND GENBALOGY,177. PIKE, JOHN,SR, Wi of, 64. BRIDGE, THS OLD,161. PISCATAQUAPIONEERS, 191. BROWNB,RICHARD, Will of, 160. &SEX COUNTY MEN AT ARTHA HA'S VINEYARD 143; 451, 45% 191. swoas 1700, 134. ROGEILS.REV. EZEKIEL,Will of, 104. CLOU-R INSCRIPTIONS: ROGERSREV. NATHANIEL. Wi of. 6~. Ancient Buying Ground, I. SALEMCOURT RECORDSAND FI&, 61,154. Bay View Cemetery, 68. SALEMIN 1700, NO. 18, 37. Old Cemetery at knesville, 106. SALEMIN 1700, NO. 19, 72. Ancient Cemetey, West Gloucester, 152. SALEMIN 1/00, NO. 20, 114. HYMNS,THE OLD,142. SALEMIN 1700, NO. -

Explored Countless Lab- Oratories, Interviewed a Myriad of Scientists, and Prepared Thousands of News Releases, Feature Articles, Web Sites, and Multimedia Packages

Explaining Research This page intentionally left blank Explaining Research How to Reach Key Audiences to Advance Your Work Dennis Meredith 1 2010 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2010 by Dennis Meredith Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meredith, Dennis. Explaining research : how to reach key audiences to advance your work / Dennis Meredith. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-973205-0 (pbk.) 1. Communication in science. 2. Research. I. Title. Q223.M399 2010 507.2–dc22 2009031328 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my mother, Mary Gurvis Meredith. She gave me the words. This page intentionally left blank You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother. -

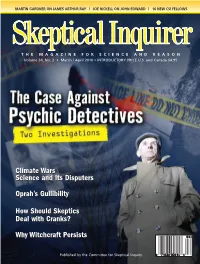

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

A Short History of the Salem Village Witchcraft Trials : Illustrated by A

iiifSj irjs . Elizabeth Howe's Trial Boston Medical Library 8 The Fenway to H to H Ex LlBRIS to H to H William Sturgis Bigelow to H to H to to Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/shorthistoryofsaOOperl . f : II ' ^ sfti. : ; Sf^,x, )" &*% "X-':K -*. m - * -\., if SsL&SfT <gHfe'- w ^ 5? '•%•; ..^ II ,».-,< s «^~ « ; , 4 r. #"'?-« •^ I ^ 1 '3?<l» p : :«|/t * * ^ff .. 'fid p dji, %; * 'gliif *9 . A SHORT HISTORY OF THE Salem Village Witchcraft Trials ILLUSTRATED BT A Verbatim Report of the Trial of Mrs. Elizabeth Howe A MEMORIAL OF HER To dance with Lapland witches, while the lab'ring moon eclipses at their charms. —Paradise Lost, ii. 662 MAP AND HALF TONE ILLUSTRATIONS SALEM, MASS.: M. V. B. PERLEY, Publisher 1911 OPYBIGHT, 1911 By M. V. B. PERLEY Saeem, Mass. nJtrt^ BOSTON 1911 NOTICE Greater Salem, the province of Governors Conant and Endicott, is visited by thousands of sojourners yearly. They come to study the Quakers and the witches, to picture the manses of the latter and the stately mansions of Salem's commercial kings, and breathe the salubrious air of "old gray ocean." The witchcraft "delusion" is generally the first topic of inquiry, and the earnest desire of those people with notebook in hand to aid the memory in chronicling answers, suggested this monograph and urged its publication. There is another cogent reason: the popular knowledge is circumscribed and even that needs correcting. This short history meets that earnest desire; it gives the origin, growth, and death of the hideous monster; it gives dates, courts, and names of places, jurors, witnesses, and those hanged; it names and explains certain "men and things" that are concomitant to the trials, with which the reader may not be conversant and which are necessary to the proper setting of the trials in one's mind; it compasses the salient features of witchcraft history, so that the story of the 1692 "delusion" may be garnered and entertainingly rehearsed. -

Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: an Authoritative Edition

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 1-12-2005 Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition Paul Melvin Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Wise, Paul Melvin, "Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S WONDERS OF THE INVISIBLE WORLD: AN AUTHORITATIVE EDITION by PAUL M. WISE Under the direction of Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT In Wonders of the Invisible World, Cotton Mather applies both his views on witchcraft and his millennial calculations to events at Salem in 1692. Although this infamous treatise served as the official chronicle and apologia of the 1692 witch trials, and excerpts from Wonders of the Invisible World are widely anthologized, no annotated critical edition of the entire work has appeared since the nineteenth century. This present edition seeks to remedy this lacuna in modern scholarship, presenting Mather’s seventeenth-century text next to an integrated theory of the natural causes of the Salem witch panic. The likely causes of Salem’s bewitchment, viewed alongside Mather’s implausible explanations, expose his disingenuousness in writing about Salem. Chapter one of my introduction posits the probability that a group of conspirators, led by the Rev. -

The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: the Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered Susan Kay Ocksreider College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ocksreider, Susan Kay, "The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625278. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7p31-h828 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS FROM A LEGAL PERSPECTIVE; THE IMPORTANCE OF SPECTRAL EVIDENCE RECONSIDERED A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of Williams and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan K. Ocksreider 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626505 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626505 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). -

List of Phobias and Simple Cures.Pdf

Phobia This article is about the clinical psychology. For other uses, see Phobia (disambiguation). A phobia (from the Greek: φόβος, Phóbos, meaning "fear" or "morbid fear") is, when used in the context of clinical psychology, a type of anxiety disorder, usually defined as a persistent fear of an object or situation in which the sufferer commits to great lengths in avoiding, typically disproportional to the actual danger posed, often being recognized as irrational. In the event the phobia cannot be avoided entirely the sufferer will endure the situation or object with marked distress and significant interference in social or occupational activities.[1] The terms distress and impairment as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) should also take into account the context of the sufferer's environment if attempting a diagnosis. The DSM-IV-TR states that if a phobic stimulus, whether it be an object or a social situation, is absent entirely in an environment - a diagnosis cannot be made. An example of this situation would be an individual who has a fear of mice (Suriphobia) but lives in an area devoid of mice. Even though the concept of mice causes marked distress and impairment within the individual, because the individual does not encounter mice in the environment no actual distress or impairment is ever experienced. Proximity and the degree to which escape from the phobic stimulus should also be considered. As the sufferer approaches a phobic stimulus, anxiety levels increase (e.g. as one gets closer to a snake, fear increases in ophidiophobia), and the degree to which escape of the phobic stimulus is limited and has the effect of varying the intensity of fear in instances such as riding an elevator (e.g. -

Radicals, Conservatives, and the Salem Witchcraft Crisis

Griffiths 1 RADICALS, CONSERVATIVES, AND THE SALEM WITCHCRAFT CRISIS: EXPLOITING THE FRAGILE COMMUNITIES OF COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University By Megan Rose Griffiths s1895850 13 June 2017 Supervisor: Dr. Johanna C. Kardux Second reader: Dr. Eduard van de Bilt Griffiths 2 Table of Contents Introduction: A New Interpretation………………………………………………....… ……..4 Chapter One: Historiography....................................................................................................11 Chapter Two: The Background to the Crisis: Fragile Communities.........................................18 Puritanism……………………………………………………………….……..18 Massachusetts, 1620-1692……………………………………………...……...21 A “Mentality of Invasion”……………………………………………...……...24 The Lower Orders of the Hierarchy…………………………………………....26 Christian Israel Falling........................................................................................31 Salem, 1630-1692: The Town and the Village...................................................33 Chapter Three: The Radicals.....................................................................................................36 The Demographic Makeup of the Radicals……………………..……....……..38 A Conscious Rebellion……………………………..……….…………..….…..42 Young Rebels………………………………………………….……….……....45 Change at the Root…………………………………………...……....…….......49 The Witches as Rebels: Unruly Turbulent Spirits…………………...…..…......53 The Witches as Radicals: The Devil’s Kingdom……………………...…….....58 Chapter Four: The Conservatives...............................................................................................64