Meeting Summary Master Plan of Aligned Use and Water Management at Hiawatha Golf Course Property, a Part of Nokomis‐Hiawatha Regional Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native American Context Statement and Reconnaissance Level Survey Supplement

NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for The City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC FINAL July 2016 Cover Image Indian Tepees on the Site of Bridge Square with the John H. Stevens House, 1852 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 583) Minneapolis Pow Wow, 1951 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 35609) Minneapolis American Indian Center 1530 E Franklin Avenue NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development 250 South 4th Street Room 300, Public Service Center Minneapolis, MN 55415 Prepared by Eva B. Terrell, M.A. and Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 FINAL July 2016 MINNEAPOLIS NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT This project is funded by the City of Minneapolis and with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. -

Lake Smetana Water Quality Study Use Attainability Analysis (Updated from 2003)

Lake Smetana Water Quality Study Use Attainability Analysis (Updated from 2003) Prepared for Nine Mile Creek Watershed District February 2020 4300 MarketPointe Drive, Suite 200 Minneapolis, MN 55435 952.832.2600 www.barr.com REPORT SUMMARY Lake Smetana Water Quality Study Use Attainability Analysis Update for Lake Smetana (2019) Prepared for Nine Mile Creek Watershed District February 2020 MANAGING LAKE SMETANA WATER QUALITY WORKING TO MEET DISTRICT GOALS Lake Smetana is a shallow, 56-acre lake within the “Golden Triangle” area of Eden Prairie, an industrial park surrounded by Interstate 494 and U.S. Highways 212 and 169. The lake is situated along the South Fork of Nine Mile Creek, approximately 1.3 stream miles downstream of Bryant Lake within the Nine Mile Creek watershed. With an average depth of 3 feet and maximum depth of 10 feet, the lake’s shallow nature and urbanized watershed pose water quality challenges. Although improved in recent years, water quality in Lake Smetana has historically been moderate to poor. The Nine Mile Creek Watershed District (NMCWD), a local unit of government that works to solve and prevent water-related problems, conducted a study of Lake Smetana in 2019 to evaluate current water quality and identify protection and improvement strategies. Additional information on the current lake conditions, water quality challenges, and recommended management strategies are summarized in this project overview. Protecting and enhancing the water quality of the lakes within the Nine Mile Creek watershed is one of the primary goals of the Nine Mile Creek Watershed District. The NMCWD’s lake management program includes data collection (monitoring), assessment (e.g., studies), and implementation of projects and programs to protect and improve water quality and aquatic habitat. -

HISTORIC Irene Fernando Is One of the First WINS Hennepin County Commissioners of Color to Sit on the Board in Its 150 Year History Page 22

NORTHNovember 29, 2018 • Serving the neighborhoods of NorthNEWS Minneapolis • www.mynorthnews.org ALSO INSIDE Remembering Donise White Page 21 Your guide to shopping local for the holidays Page 7 Irene Fernando celebrates her election night win with two of her supporters. HISTORIC Irene Fernando is one of the first WINS Hennepin County Commissioners of color to sit on the board in its 150 year history Page 22 Your 2018 midterm election rundown Page 11 2 • North News • November 29, 2018 NORTHnews by and so many of us become de- surrounded by dreamers. Dreamers vestment can be overcome, that resil- tached from the people and cultures like the folks that make up Pillsbury iency will win, that new ways of exist- they came from in the first place. This United Communities’ leadership team ing less violently together as humans time of year, I question my relation- who invited truth-teller Shaun King to will manifest in our lifetimes. Houston ship with the Thanksgiving story. As be the organization’s annual fundrais- is still dreaming and has created a my family celebrates the holiday with er’s keynote speaker (Page 16). scholarship fund in his wife's name. a feast, football, and a turkey trot, it’s Dreamers like many of our new elect- Read about it on Page 21. easy to sideline the stories our cele- ed officials, who are bringing under— As this holiday season continues, I’ll Letter from the Editor brations stem from and become com- and never—represented identities be enjoying time with my family, in- plicit in erasing our country's history and new ideas to positions of power. -

Lake Calhoun Center 3033 Excelsior Boulevard | Minneapolis, MN 55416

OFFICE SPACE FOR LEASE Lake Calhoun Center 3033 Excelsior Boulevard | Minneapolis, MN 55416 Property Description Current Availability Lake Calhoun Center is a Class A office building 3rd Floor | Suites 300 & 320 adjacent to Bde Maka Ska on the western edge Contiguous 23,880 SF of Uptown. The upper floors offer tenants some Available 12.1.2019 of the most spectacular views in Minneapolis with the northeast side overlooking Uptown and the Property Highlights southeast side overlooking the lake. • Abundant off-street parking; executive garage parking with complimentary valet service The property’s back entrance opens onto a large • Indoor bike parking and storage green space which folds down to a trail that • On-site property management encircles the lake. This trail is both pedestrian and • Contemporary common spaces, artwork and bike friendly, and in summer the lake is dotted with sculptures wind surfers, sailboats and paddle boards. • On-site fitness center, locker rooms, café, salon Lake Calhoun Center is digital savvy, dog friendly, and conference rooms and close to everything – making it one of the • Stunning lake views most iconic and trendy office locations in all of • Security system Minneapolis. • Steps from Bde Maka Ska beach and trails Michelle Schmitt 612.924.6411 | [email protected] | Ackerberg.com The Ackerberg Group, 3033 Excelsior Blvd. Ste 10, Minneapolis, MN 55416 Area Highlights • Less than 10 minutes from Hwy 100 & I-394 • Across the street from two distinct shopping centers which include coffee shops, fitness centers, grocery stores and restaurants • Access to all the amenities of Uptown including restaurants, hotels, executive housing, retail and entertainment • Easy access to the Midtown Greenway and Minneapolis Chain of Lakes • Steps from Bde Maka Ska beach and trail • 15 minutes from Downtown Minneapolis Area Map Michelle Schmitt 612.924.6411 | [email protected] | Ackerberg.com The Ackerberg Group, 3033 Excelsior Blvd. -

Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) Site Design Community Meeting #2

Artwork by Marlena Myles, 2017 Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) Site Design Community Meeting #2 1 2 Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) 3 4 5 6 Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) 7 Bde Maka Ska – White Earth Lake (Lake Calhoun) Mahpiya Wicasta – Cloud Man Heyata Otunwe – Village to the Side “Sioux Village, Lake Calhoun, Near Fort Snelling: 1835” painting by George Caitlin 8 9 1 Taliaferro map 1830 0 11 12 Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) 13 Seeking visual and literary artists to: • Collaborate on the gathering space and encounters around the Lake • Incorporate visual and literary elements into the site design. • (May also include individual public art works). • Serve contemplative, ceremonial and educational uses. • Celebrate Dakota history, language, imagery and values. • Incorporate input from descendants, the Native American and urban community. 14 15 Bde Maka Ska (Lake Calhoun) 16 Summary of Key Comments Heard So Far Honor the original inhabitants of Heyata Recognize the challenges at this site: Masses of Otunwe, and tell the story of Cloud Man, the people, one time visitors and repeat visitors, village and its generosity. multiple uses, and integration into non-native surroundings. Make a connection between past, current and future generations of the Dakota and native Don’t include a lot of cement and structures. peoples, including native women. Keep it simple and reduce site disturbance. Make it a welcoming space for those who have Create a space that could serve for reflection been living in exile--a space grounded in Dakota and prayer, communal gathering, teaching language and values. classes, exhibits and other programming. -

Bringing Broadband Communication to Tribes

NEWS FROM US to review dark history of Indigo Girls/Line 3 activists host New work by Native artist to A NATIVE Indigenous boarding schools Protect the Water concert rise where “Scaffold” stood AMERICAN PERSPECTIVE 40 YEARS OF SERVING THE NATIVE AMERICAN COMMUNITY WWW.THECIRCLENEWS.ORG [email protected] Like us on Facebook! Follow Us on Twitter page 4 page 6 page 14 Facebook.com/TheCircleNews @TheCircleNews FREE JULY 2021 • VOLUME 42, ISSUE 7 FREE Bringing broadband communication to tribes Minneapolis groups seeks to rename Columbus Avenue to Oyate BY HANNAH BROADBENT organizers, every attendee being from the neighborhood. Maltzman says she can recall don’t know how to the disdain for the name exist- talk about what it’s ing since she moved in, in “Ilike to live on 2008. Though block members ‘Columbus Avenue’ without can recall it going back another standing on a soapbox talking 20 years. about everything that is wrong “A lot of us would talk about with colonization,” Quito our address as 33–f*** Ziegler said at the Oyate Columbus Avenue,” she said. Avenue information sharing Maltzman said it was summer and community meeting in of 2020 that triggered a few Minneapolis. street artists to take it upon ‘Oyate Avenue’ is the name themselves throughout the that a group of community avenue to paint over the signs members would like to change with a different name. On 38th ‘Columbus Avenue’ to. ‘Oyate’ and Columbus the avenue sign Turtle Island Communications workers lay fiber cables on reservation lands. (Photo courtesy of Turtle Island was given to them by Makoce is now red and reads “Little Communications.) Ikikcupi, a land recovery proj- Crow”. -

Surface Water Management Plan Water Resources | City of St

Surface Water Management Plan Water Resources | City of St. Louis Park Proposals are due 4:00 p.m. April 24, 2017 Executive Summary City of St. Louis Park Surface Water Management Plan Executive Summary Located in Hennepin County just west of Minneapolis, the 10.7-square-mile City of St. Louis Park is a fully developed suburban community. The population of St. Louis Park is approximately 48,000 residents, making it the 20th largest city in Minnesota. St. Louis Park contains a variety of physical and water resources including several wetlands and small lakes, wooded areas, parks, and recreational lands, as well as the Minnehaha Creek corridor. Two watershed management organizations (WMOs) cover St. Louis Park, each with its own governing body: the Bassett Creek Watershed Management Commission (BCWMC) and the Minnehaha Creek Watershed District (MCWD). This local Surface Water Management Plan (SWMP) was prepared in accordance with Minnesota Statute 103B.235 and Minnesota Rules 8410 and is intended to replace the 2009 plan. The purpose of this SWMP includes objectives outlined in Minnesota Statute 103B.201 for metropolitan water management programs. According to the statute, the purposes of these water management programs are to: • protect, preserve, and properly use natural surface and groundwater storage and retention systems; • minimize public capital expenditures needed to correct flooding and water quality problems; • identify and plan for means to effectively protect and improve surface and groundwater quality; • establish more uniform local policies and official controls for surface and groundwater management; • prevent the erosion of soil into surface water systems; • promote effective groundwater recharge; • protect and enhance fish and wildlife habitats and water recreational facilities; and • secure the other benefits associated with the proper management of surface and groundwater. -

Minneapolis Chain of Lakes

Wa Bryn Mawr y y zata Blvd N Parade Minneapolis w Meadows Sculpture Portland Ave k Ice Garden 394 P Garden Loring h 394 Park t r i BRYN MAWR Minneapolis Walker LORING W LOWRY HILL Convention e Art Center Brownie r Cedar Lake Tr Center o y PARK Valley d w Oak Grove St 15th St Steele Golden Lake o k Lowry e P Sq h T od Park Cedar Lake Tr o w North en Stevens K 94 Square Cedar Lake Kenwood Stevens Reg Tr Park Ctr for S Park the Arts e Kenilworth Tr v A Nicollet Ave Lasalle Ave Lasalle g Franklin Ave W Franklin Ave E e n i v S w KENWOOD A E e E n v i y p A Hennepin w e Cedar n k n History n Cedar n P e Washburn y e Museum w s Point P H Fair Oaks k le P Lake Beach 24th St W Is WHITTIER LOWRY eet” e EAST e r k Minneapolis h a t Lyndale Ave S L HILL EAST f ISLES Institute r o of Arts Children’s a e “THE WEDGE” d k Theater e L a a L of Mpls C Levin Mueller “Eat St k Minneapolis e Triangle Park College of o f 26th St W Art & Design t h e Phoenix I Lake s Theater Whittier Cedar South l W e Park Beach s P of the 1st Ave S k D w e y a W Isles 28th St W n Sunset Blvd P Intermedia k CEDAR w Arts y Midtown Greenway Kenilworth Tr France Ave S ISLES Park Lagoon Cinema Bryant- DEAN Lagoon Ave Lake St Louis Jungle Calhoun Calhoun Bowl Lake St W Village North Uptown Thtr Lake St W Theater Lake St E Beach y W Highpoint a Calhoun w y Square Center for LYN-LAKE n w e Calhoun k Printmaking re P 31st St W 31st St E G Commons n n Portland Ave Cedar Lake w u UPTOWN to o Bryant LRT Reg Tr id lh M a Square C 32nd St Beach CENTRAL LYNDALE SOUTH UPTOWN Painter Bass -

Seth Eastman a Biography Fort Snelling & the Dakota People Timeline

Seth Eastman a biography Fort Snelling & the Dakota People Timeline Seth Eastman was born on January 24, 1808, in Brunswick, Maine. The oldest The artist returned to West Fort Snelling was constructed in 1820 at the confluence of thirteen children, he became interested in joining the military at an early Point to teach drawing of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, a site which had age. He entered West Point Military Academy at sixteen and spent five years in 1833, and shortly been occupied by humans for thousands of years. It was a 1800 studying sketching and topography. After graduating in 1830, the military afterwards, in 1835, self-contained community, with a blacksmith, doctor, and transferred him to Fort Snelling in what is now Saint Paul, Minnesota. Fort married his second wife. barber living at the Fort. Men assigned there resided in the Snelling was first established after the War of 1812 to help control the fur Mary Henderson (1818– barracks with their families. Seth Eastman was stationed trade between Indigenous peoples and American fur traders, as well as to 1887), the daughter of there twice: his first assignment was 1830–1832, and maintain a line of defense against the British troops in the Northwest. During a military surgeon, was his second was 1841–1848 where he served as the Fort’s his time stationed there, Eastman familiarized himself with native culture, also interested in Native commander four times. The years he spent at Fort Snelling 1808 Seth Eastman was born on studying the language as well as the traditional dress and lifestyle of the local American culture and deeply influenced his art. -

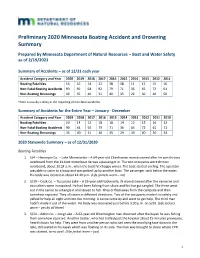

2020 Minnesota Boating Accident and Drowning Summary

, Preliminary 2020 Minnesota Boating Accident and Drowning Summary Prepared by Minnesota Department of Natural Resources – Boat and Water Safety as of 2/19/2021 Summary of Accidents – as of 12/31 each year Accident Category and Year 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 Boating Fatalities 16 10 14 12 18 18 14 12 15 16 Non-Fatal Boating Accidents 90 90 64 92 79 71 36 65 72 61 Non-Boating Drownings 49 35 40 31 40 35 29 30 40 50 There is usually a delay in the reporting of non-fatal accidents. Summary of Accidents for the Entire Year – January - December Accident Category and Year 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 Boating Fatalities 10 14 12 18 18 14 12 15 16 12 Non-Fatal Boating Accidents 90 64 92 79 71 36 65 72 61 71 Non-Boating Drownings 35 40 31 40 35 29 30 40 50 34 2020 Statewide Summary – as of 12/31/2020 Boating Fatalities 1. 5/4 – Hennepin Co. – Lake Minnetonka – A 64-year-old Chanhassen man drowned after he was thrown overboard from the 14-foot motorboat he was a passenger in. The two occupants were thrown overboard, about 10:24 a.m., when the boat hit choppy waves. The boat started circling. The operator was able to swim to a buoy and was picked up by another boat. The passenger sank below the water. His body was located at about 12:40 p.m. (Life jackets worn – no) 2. 5/19 – Cook Co. -

The Midtown Greenway

Midtown Greenway trail access Ramsey Hennepin Welcome to the Midtown Greenway MPLS Saint Paul The Midtown Greenway is a 6 mile multi-use trail in a historic railroad trench linking parks, trails, businesses, and cultural destinations between the Midtown Greenway Mississippi River and the Chain of Lakes. The trail runs parallel to nearby Lake Street, a home to arts and cultural organizations, major institutions, and a diverse community of small local businesses. S S S S R d Minneapolis a Summit Ave e i o 1 v e e ilr e LORING PARK Riverside Park e e Ra Cedar 18th St E v Murphy 8th St S PROSPEC T PARK - v r v F v 7 s S v 94 Jewish Day N A 65 id B A t A A 55 Augsburg e Kenwood A h 94 Square r n P A EAST RIVER ROAD S s West River School Lake x Butler Pl v e x Lincoln Ave Lincoln Ave Stevens College e o A e e 94 e S v a t o S A v f Square Trinity First n v i l Parkway E e n Park n l E m To n S 19th St E e n i e 19th St E S v Park a o l a Lutheran S K O v d e S Downtown t i J C A Franklin Pedestrian E A C r STEVEN'S SQUARE - t v F A ra S e S n Mississippi v k Bridge S l Minneapolis g in Franklin Avenue A h Kenwood t R A k BRYN - l t S e ve LOWRY HILL n National River i i n LORING HEIGHTS W v c i Station S n Library i c S Elementary VENTURA Franklin Ave E e o and Recreation K S o r w e d MAWR 5 w p T s E e School r r C e Area (MNRRA) S e r 5 S u Hennepin S VILLAGE o n r S a e v e S E f e e M D w Peavey v LAKE FOREST e 21st S S A t E Elementary e e S d v Takoda W v M m v S v A S S v t Cedar Lake o e e e A A E e A 21st St W e i Charter S Forest -

2017 Water Resources Report

Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board WATER RESOURCES REPORT 2017 Environmental Management 2017 WATER RESOURCES REPORT Prepared by: Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board Environmental Management 3800 Bryant Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55409-1029 612.230.6400 www.minneapolisparks.org December 2018 Funding provided by: Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board City of Minneapolis Public Works Copyright © 2018 by the Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board Material may be quoted with attribution. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. i Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... iv 1. Monitoring Program Overview .............................................................................................. 1-1 2. Birch Pond .............................................................................................................................. 2-1 3. Brownie Lake ......................................................................................................................... 3-1 4. Calhoun / Bde Maka Ska ........................................................................................................ 4-1 5. Cedar Lake ............................................................................................................................. 5-1 6. Diamond Lake .......................................................................................................................