Diet of Moreporks (Ninox Novaeseelandiae) in Pureora Forest Determined from Prey Remains in Regurgitated Pellets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

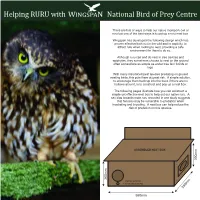

(Ruru) Nest Box

Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre There are lots of ways to help our native morepork owl or ruru but one of the best ways is to put up a ruru nest box. Wingspan has developed the following design which has proven effective both out in the wild and in captivity, to attract ruru when looking to nest, providing a safe environment for them to do so. Although ruru can and do nest in tree cavities and epiphytes, they sometimes choose to nest on the ground often somewhere as simple as under tree fern fronds or logs. With many introduced pest species predating on ground nesting birds, this puts them at great risk. A simple solution, to encourage them back up into the trees if there are no hollows around, is to construct and pop up a nest box. The following pages illustrate how you can construct a simple yet effective nest box to help out our native ruru. A sex bias towards male ruru recorded in one study suggests that females may be vulnerable to predation when incubating and brooding. A nest box can help reduce the risk of predation on this species. ASSEMBLED NEST BOX 300mm 260mm ENTRY PERCH < ATTACHED HERE 260mm 580mm Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre MATERIALS: + 12mm tanalised plywood + Galvanised screws 30mm (x39) Galvanised screws 20mm (x2 for access panel) DIMENSIONS: Top: 300 x 650mm Front: 245 x 580mm Back: 350 x 580mm Base: 260 x 580mm Ends: 260 x 260 x 300mm Door: 150 x 150mm Entrance & Access Holes: 100mm + + + TOP + 300x650mm + + + + + + + + BACK 350x580mm + + + + ACCESS + + FRONT + HOLE + 100x100 ENTRANCE 245x580mm HOLE END 100x100 END 260x260x300mm 260x260x300mm + + + + + + + + + + + ACCESS COVER 150x150mm + BASE + 260x580mm + + + + + Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre INSTRUCTIONS FOR RURU NEST BOX ASSEMBLY: Screw front and back onto inside edge of base (4 screws along each edge using pre-drilled holes). -

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu O Aotearoa No.24 December 2019

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu o Aotearoa No.24 December 2019 The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NO.24 DECEMBER 2019 Proud sponsors of Birds New Zealand From the President's Desk Find us in your local 3 New World or PAKn’ Save 4 NZ Bird Conference & AGM 2020 5 First Summer of NZ Bird Atlas 6 Birds New Zealand Research Fund 2019 8 Solomon Islands – Monarchs & Megapodes 12 The Inspiration of Birds – Mike Ashbee 15 Aka Aka swampbird Youth Camp 16 Regional Roundup PUBLISHERS Published on behalf of the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand 19 Bird News (Inc), P.O. Box 834, Nelson 7040, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] Website: www.birdsnz.org.nz Editor: Michael Szabo, 6/238 The Esplanade, Island Bay, Wellington 6023. Email: [email protected] Tel: (04) 383 5784 COVER IMAGE ISSN 2357-1586 (Print) ISSN 2357-1594 (Online) Morepork or Ruru. Photo by Mike Ashbee. We welcome advertising enquiries. Free classified ads for members are at the https://www.mikeashbeephotography.com/ editor’s discretion. Articles or illustrations related to birds in New Zealand and the South Pacific region are welcome in electronic form, such as news about birds, members’ activities, birding sites, identification, letters, reviews, or photographs. Letter to the Editor – Conservation Copy deadlines are 10th Feb, May, Aug and 1st Nov. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily represent those of OSNZ (Inc) or the editor. Birds New Zealand has a proud history of research, but times are changing and most New Zealand bird species are declining in numbers. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

New Zealand 9Th – 25Th January 2020 (27 Days) Chatham Islands Extension 25Th – 28Th January 2020 (4 Days) Trip Report

New Zealand 9th – 25th January 2020 (27 Days) Chatham Islands Extension 25th – 28th January 2020 (4 Days) Trip Report The Rare New Zealand Storm Petrel, Hauraki Gulf by Erik Forsyth Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader Erik Forsyth Trip Report – RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive I 2020 2 Tour Summary After a brief get together this morning, we headed to a nearby estuary to look for wading birds on the incoming tide. It worked out well for us as the tide was pushing in nicely and loads of Bart-tailed Godwits could be seen coming closer towards us. Scanning through the flock we could found many Red Knot as well as our target bird for this site, the endemic Wrybill. About 100 of the latter were noted and great scope looks were enjoyed. Other notable species included singletons of Double-banded and New Zealand Plovers as well as Paradise Shelduck all of which were endemics! After this good start, we headed North to the Muriwai Gannet Colony, arriving late morning. The breeding season was in full The Endangered Takahe, Tiritiri Matangi Island swing with many Australasian Gannets by Erik Forsyth feeding large chicks. Elegant White-fronted Terns were seen over-head and Silver and Kelp Gulls were feeding chicks as well. In the surrounding Flax Bushes, a few people saw the endemic Tui, a large nectar-feeding honeyeater as well as a Dunnock. From Muriwai, we drove to east stopping briefly for lunch at a roadside picnic area. Arriving at our hotel in the late afternoon, we had time to rest and prepare for our night walk. -

An Investigation of Causes of Disease Among

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. An investigation of causes of disease among wild and captive New Zealand falcons (Falco novaeseelandiae), Australasian harriers (Circus approximans) and moreporks (Ninox novaeseelandiae). A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Veterinary Science at Massey University, Turitea, Palmerston North, New Zealand Mirza Vaseem 2014 ABSTRACT Infectious disease can play a role in the population dynamics of wildlife species. The introduction of exotic birds and mammals into New Zealand has led to the introduction of novel diseases into the New Zealand avifauna such as avian malaria and toxoplasmosis. However the role of disease in New Zealand’s raptor population has not been widely reported. This study aims at investigating the presence and prevalence of disease among wild and captive New Zealand falcons (Falco novaeseelandiae), Australasian harrier (Circus approximans) and moreporks (Ninox novaeseelandiae). A retrospective study of post-mortem databases (the Huia database and the Massey University post-mortem database) undertaKen to determine the major causes of mortality in New Zealand’s raptors between 1990 and 2014 revealed that trauma and infectious agents were the most frequently encountered causes of death in these birds. However, except for a single case report of serratospiculosis in a New Zealand falcon observed by Green et al in 2006, no other infectious agents have been reported among the country’s raptors to date in the peer reviewed literature. -

Anticoagulant Rodenticide Exposure in an Australian Predatory Bird Increases with Proximity to Developed Habitat

Science of the Total Environment 643 (2018) 134–144 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in an Australian predatory bird increases with proximity to developed habitat Michael T. Lohr School of Science, Edith Cowan University, 100 Joondalup Drive, Joondalup, Western Australia 6027, Australia HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Anticoagulant rodenticide (AR) exposure rates are poorly studied in Australian wildlife. • ARs were detected in 72.6% of Southern Boobook owls found dead or moribund in Western Australia. • Total AR exposure correlated with prox- imity to developed habitat. • ARsusedonlybylicensedpesticideappli- cators were detected in owls. • Raptors with larger home ranges and more mammal-based diets may be at greater risk of AR exposure. article info abstract Article history: Anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs) are commonly used worldwide to control commensal rodents. Second gener- Received 10 May 2018 ation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) are highly persistent and have the potential to cause secondary poison- Received in revised form 16 June 2018 ing in wildlife. To date no comprehensive assessment has been conducted on AR residues in Australian wildlife. Accepted 17 June 2018 My aim was to measure AR exposure in a common widespread owl species, the Southern Boobook (Ninox Available online xxxx boobook) using boobooks found dead or moribund in order to assess the spatial distribution of this potential Editor: D. Barcelo threat. A high percentage of boobooks were exposed (72.6%) and many showed potentially dangerous levels of AR residue (N0.1 mg/kg) in liver tissue (50.7%). Multiple rodenticides were detected in the livers of 38.4% of Keywords: boobooks tested. -

Birds at Tawharanui Open Sanctuary

For millions of years our precious birds evolved with no mammalian pests. They were unprepared when Morepork, Native. Birds at man arrived along with creatures that could chase Morepork roost during and sniff them out. Birds and their nests were the day in thick Tawharanui Open Sanctuary decimated. Our birds need our help to survive. vegetation. Morepork eat mice, (A full bird list is available at the office.) NZ Dotterel Endemic. spiders and baby birds. NZ dotterel are losing Morepork may be seen beach habitat to humans during the day when and housing. They are bellbirds and tui gang up disturbed by dogs and to drive them away from suffer predation by cats, their territories. They are stoats, and rats. They return regularly heard at night. every year to their nesting territories. Ten pairs make Tawharanui their home. Variable Oystercatcher Endemic. From juveniles to breeding age takes seven years. They can be seen feeding on the beaches and amongst the rocks. They can be very noisy and aggressive when protecting nests. Takahe are endemic. (They are only found in NZ.) Takahe can’t fly as they evolved in New Zealand with Black-backed Gull no ground predators. Since 2014 fourteen have been Unprotected, native. released at Tawharanui through the Department of They scavenge and eat North Island Brown Kiwi Endemic. Conservation Takahe Recovery Programme. They all food scraps, fish, worms Kiwi were introduced to Tawharanui in 2006. If you have radio transmitters and are monitored carefully. and small chicks. At carry a torch covered in red cellophane and are Tawharanui some cruise very quiet in Ecology Bush you may hear them on the updraft created scratching around in the forest floor. -

A Preliminary Study on the Diet and Breeding Success of Ruru

A preliminary study on the diet and breeding success of ruru (Ninox novaeseelandiae) on Tiritiri Matangi Island Sarah Busbridge 2017 This research project was carried out on Tiritiri Matangi Island under a general permit from the Department of Conservation (SKMBT_C280 14121208320) which allows for non-invasive research and monitoring of flora and fauna on the Island. The study was funded by the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, Inc. Field work was carried out between October 2016 and February 2017. Suggested citation: Busbridge, S. 2017. A preliminary study on the diet and breeding success of ruru (Ninox novaeseelandiae) on Tiritiri Matangi Island. Unpublished Report. The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, Auckland. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents ................................................................................................................. 3 List of tables ........................................................................................................................ 4 List of figures ....................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 Methods ............................................................................................................................. -

Identification and Description of Feathers in Te Papa's Mäori Cloaks

Tuhinga 22: 125–147 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2011) Identification and description of feathers in Te Papa’s Mäori cloaks Hokimate P. Harwood Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: For the first time, scientific research was undertaken to identify the feathers to species level contained in 110 cloaks (käkahu) held in the Mäori collections of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa). Methods of feather identification involved a visual comparison of cloak feathers with museum bird specimens and analysis of the microscopic structure of the down of feathers to verify bird order. The feathers of more than 30 species of bird were identified in the cloaks, and consisted of a wide range of native and introduced bird species. This study provides insight into understanding the knowledge and production surrounding the use of materials in the cloaks; it also documents the species of bird and the use of feathers included in the cloaks in Te Papa’s collections from a need to have detailed and accurate museum records. KEYWORDS: Mäori feather cloaks, käkahu, cloak weaving, birds, feathers, harakeke, microscopic feather identification, barbule, nodes, New Zealand. Introduction (whatu aho rua) was used to secure attachments such as feathers, and hence was chosen for more decorative cloaks The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) (Pendergrast 1987: 14). The feathers were typically bunched houses more than 300 Mäori käkahu (cloaks), of which 110 or butted together and woven into the cloak as it was being incorporate feathers. -

Checklist Bruny Island Birds

Checklist of bird species found on Bruny Island INALA-BRUNY ISLAND PTY LTD Dr. Tonia Cochran Inala 320 Cloudy Bay Road Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia 7150 Phone: +61-3-6293-1217; Fax: +61-3-6293-1082 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.inalabruny.com.au 11th Edition April 2015 Total Species for Bruny Island: 150 Total species for Inala: 95 * indicates seen on the Inala property Tasmania's 12 Endemic Species (listed in the main checklist as well) 52 Tasmanian Native-hen* Tribonyx mortierii 82 Green Rosella* Platycercus caledonicus 100 Yellow-throated Honeyeater* Lichenostomus flavicollis 101 Strong-billed Honeyeater* Melithreptus validirostris 102 Black-headed Honeyeater* Melithreptus affinis 104 Yellow Wattlebird* Anthochaera paradoxa 111 Forty-spotted Pardalote* Pardalotus quadragintus 113 Scrubtit* Acanthornis magna 115 Tasmanian Scrubwren* Sericornis humilis 117 Tasmanian Thornbill* Acanthiza ewingii 121 Black Currawong* Strepera fuliginosa 134 Dusky Robin* Melanodryas vittata Species Scientific Name Galliformes 1 Brown Quail* Coturnix ypsilophora Anseriformes 2 Cape Barren Goose (rare vagrant to Bruny) Cereopsis novaehollandiae 3 Black Swan* Cygnus atratus 4 Australian Shelduck Tadorna tadornoides 5 Maned Duck (Aust. Wood Duck)* Chenonetta jubata 6 Mallard (introduced) Anas platyrhynchos 7 Pacific Black Duck* (partial migrant) Anas superciliosa 8 Australasian Shoveler Anas rhynchotis 9 Grey Teal* (partial migrant) Anas gracilis 10 Chestnut Teal* (partial migrant) Anas castanea 11 Musk Duck Biziura lobata Sphenisciformes -

Vocalisations of the New Zealand Morepork (Ninox Novaeseelandiae) on Ponui Island

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Vocalisations of the New Zealand Morepork (Ninox novaeseelandiae) on Ponui Island A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Alex Brighten 2015 iv Abstract Vocalisations provide an effective way to overcome the challenge of studying the behaviour of cryptic or nocturnal species. Knowledge of vocalisations can be applied to management strategies such as population census, monitoring, and territory mapping. The New Zealand Morepork (Ninox novaeseelandiae) is a nocturnal raptor and, to date, there has been little research into their vocalisations even though this offers a key method for monitoring morepork populations. Although not at risk, population monitoring of morepork will help detect population size changes in this avian predator which may prey on native endangered fauna and may suffer secondary poisoning. This study investigated the vocal ecology of morepork on Ponui Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand from April 2013 to April 2014. The initial goal was to develop a monitoring method for morepork. However, due to a lack of detailed basic knowledge of their vocalisations, the primary objective shifted to filling that knowledge gap and providing baseline data for future research. The aims of this study were thus to characterise all of the calls given by the morepork on the island; to investigate spectral and temporal parameters of three main calls; to plot the amount of calling across a night and a year; and to study the responses of morepork to playback calls. -

Avian Phylogeny and Divergence Times Based on Mitogenomic

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Avian phylogeny and divergence times based on mitogenomic sequences Kerryn Elizabeth Slack 2012 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Genetics Institute of Molecular BioSciences Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand page i Abstract Despite decades of research using a variety of data sources (such as morphological, paleontological, immunological, DNA hybridization and short DNA sequences) both the relationships between modern bird orders and their times of origin remain uncertain. Complete mitochondrial (mt) genomes have been extensively used to study mammalian and fish evolution. However, at the very beginning of my study only the chicken mt sequence was available for birds, though seven more avian mt genomes were published soon after. In order to address these issues, I sequenced eight new bird mt genomes: four (penguin, albatross, petrel and loon) from previously unrepresented orders and four (goose, brush-turkey, gull and lyrebird) to provide improved taxon sampling. Adding these taxa to the avian mt genome dataset aids in resolving deep bird phylogeny and confirms the traditional placement of the root of the avian tree (between paleognaths and neognaths). In addition to the mt genomes, in a collaboration between paleontologists and molecular biologists, the oldest known penguin fossils (which date from 61- 62 million years ago) are described. These fossils are from the Waipara Greensand, North Canterbury, New Zealand, and establish an excellent calibration point for estimating avian divergence times.