Status and Conservation of the Norfolk Island Boobook Ninox Novaeseelandiae Undulata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ruru) Nest Box

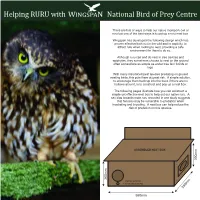

Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre There are lots of ways to help our native morepork owl or ruru but one of the best ways is to put up a ruru nest box. Wingspan has developed the following design which has proven effective both out in the wild and in captivity, to attract ruru when looking to nest, providing a safe environment for them to do so. Although ruru can and do nest in tree cavities and epiphytes, they sometimes choose to nest on the ground often somewhere as simple as under tree fern fronds or logs. With many introduced pest species predating on ground nesting birds, this puts them at great risk. A simple solution, to encourage them back up into the trees if there are no hollows around, is to construct and pop up a nest box. The following pages illustrate how you can construct a simple yet effective nest box to help out our native ruru. A sex bias towards male ruru recorded in one study suggests that females may be vulnerable to predation when incubating and brooding. A nest box can help reduce the risk of predation on this species. ASSEMBLED NEST BOX 300mm 260mm ENTRY PERCH < ATTACHED HERE 260mm 580mm Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre MATERIALS: + 12mm tanalised plywood + Galvanised screws 30mm (x39) Galvanised screws 20mm (x2 for access panel) DIMENSIONS: Top: 300 x 650mm Front: 245 x 580mm Back: 350 x 580mm Base: 260 x 580mm Ends: 260 x 260 x 300mm Door: 150 x 150mm Entrance & Access Holes: 100mm + + + TOP + 300x650mm + + + + + + + + BACK 350x580mm + + + + ACCESS + + FRONT + HOLE + 100x100 ENTRANCE 245x580mm HOLE END 100x100 END 260x260x300mm 260x260x300mm + + + + + + + + + + + ACCESS COVER 150x150mm + BASE + 260x580mm + + + + + Helping RURU with W I N G S P A N National Bird of Prey Centre INSTRUCTIONS FOR RURU NEST BOX ASSEMBLY: Screw front and back onto inside edge of base (4 screws along each edge using pre-drilled holes). -

NSW Vagrant Bird Review

an atlas of the birds of new south wales and the australian capital territory Vagrant Species Ian A.W. McAllan & David J. James The species listed here are those that have been found on very few occasions (usually less than 20 times) in NSW and the ACT, and are not known to have bred here. Species that have been recorded breeding in NSW are included in the Species Accounts sections of the three volumes, even if they have been recorded in the Atlas area less than 20 times. In determining the number of records of a species, when several birds are recorded in a short period together, or whether alive or dead, these are here referred to as a ‘set’ of records. The cut-off date for vagrant records and reports is 31 December 2019. As with the rest of the Atlas, the area covered in this account includes marine waters east from the NSW coast to 160°E. This is approximately 865 km east of the coast at its widest extent in the south of the State. The New South Wales-Queensland border lies at about 28°08’S at the coast, following the centre of Border Street through Coolangatta and Tweed Heads to Point Danger (Anon. 2001a). This means that the Britannia Seamounts, where many rare seabirds have been recorded on extended pelagic trips from Southport, Queensland, are east of the NSW coast and therefore in NSW and the Atlas area. Conversely, the lookout at Point Danger is to the north of the actual Point and in Queensland but looks over both NSW and Queensland marine waters. -

First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla Coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis Chloris from Lord Howe Island

83 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2004, 2I , 83- 85 First Records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris from Lord Howe Island GLENN FRASER 34 George Street, Horsham, Victoria 3400 Summary Details are given of the first records of two species of finch from Lord Howe Island: the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris. These records, from the early 1980s, have been quoted in several papers without the details hav ing been published. My Common Chaffinch records are the first for the species in Australian territory. Details of my records and of other published records of other European finch es on Lord Howe Island are listed, and speculation is made on the origin of these finches. Introduction This paper gives details of the first records of the Common Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs and the European Greenfinch Carduelis chloris for Lord Howe Island. The Common Chaffinch records are the first for any Australian territory and although often quoted (e.g. Boles 1988, Hutton 1991, Christidis & Boles 1994), the details have not yet been published. Other finches, the European Goldfinch C. carduelis and Common Redpoll C. fiammea, both rarely reported from Lord Howe Island, were also recorded at about the same time. Lord Howe Island (31 °32'S, 159°06'E) lies c. 800 km north-east of Sydney, N.S.W. It is 600 km from the nearest landfall in New South Wales, and 1200 km from New Zealand. Lord Howe Island is small (only 11 km long x 2.8 km wide) and dominated by two mountains, Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower, the latter rising to 866 m above sea level. -

Download Full Article 1.6MB .Pdf File

Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1962.25.10 ADDITIONS TO MARINE MOLLUSCA 177 1 May 1962 ADDITIONS TO THE MARINE MOLLUSCAN FAUNA OF SOUTH EASTERN AUSTRALIA INCLUDING DESCRIPTIONS OF NEW GENUS PILLARGINELLA, SIX NEW SPECIES AND TWO SUBSPECIES. Charles J. Gabriel, Honorary Associate in Gonchology, National Museum of Victoria. Introduction. It has always been my conviction that the spasmodic and haphazard collecting so far undertaken has not exhausted the molluscan species to be found in the deeper waters of South- eastern Australia. Only two large single collections have been made; first by the vessel " Challenger " in 1874 at Station 162 off East Moncoeur Island in 38 fathoms. These collections were described in the " Challenger " reports by Rev. Boog. Watson (Gastropoda) and E. A. Smith (Pelecypoda). In the latter was included a description of a shell Thracia watsoni not since taken in Victoria though dredged by Mr. David Howlett off St. Francis Island, South Australia. In 1910 the F. I. S. " Endeavour " made a number of hauls both north and south of Gabo Island and off Cape Everard. The u results of this collecting can be found in the Endeavour " reports. T. Iredale, 1924, published the results of shore and dredging collections made by Roy Bell. Since this time continued haphazard collecting has been carried out mostly as a hobby by trawler fishermen either for their own interest or on behalf of interested friends. Although some of this material has reached the hands of competent workers, over the years the recording of new species has probably been delayed. -

Mollusca from the Continental Shelf of Eastern Australia

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Iredale, T., 1925. Mollusca from the Continental Shelf of eastern Australia. Records of the Australian Museum 14(4): 243–270, plates xli–xliii. [9 April 1925]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.14.1925.845 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia MOLLUSCA ]"ROM THE CONTINENTAL SHELF OF EAS'rERN AUSTRALIA. By TOM IREDALE. (Plates xli-xliii, and map.) INTRODUCTION. Our knowledge of the fauna of the continental shelf is so imper fect that any additional data are acceptable. rrhis year, Mr. C. W. Mulvey, manager of the New State Fish and Ice Company, Sydney, has interested himself in assisting the Australian Museum by present ing specimens trawled by his fleet, and has given facilities for mem bers of the Museum staff to collect. The results of l\'[r. Mulvey's activities form the basis of this report. The oldest material from the continental shelf consists of a few hauls made by the" Challenger," which, curiously enough, were over looked and mixed with Atlantic material, and, when reported upon, caused a lot of trouble which, even now, needs rectification. Simul taneously the" Gazelle" made a haul or two, from which a few species were described. The" Thetis" trawled along the coast in depths up to eighty fathoms, and the study of the material by Hedley instigated further research and he continued the work until the arrival of the "Endeavour." This ship explored the shelf from end to end, but, unfortunately, through the tragic ending of the enterprise, the results are comparatively unknown. -

Action Plan for Seabird Conservation in New Zealand Part B: Non-Threatened Seabirds

Action Plan for Seabird Conservation in New Zealand Part B: Non-Threatened Seabirds THREATENED SPECIES OCCASIONAL PUBLICATION NO. 17 Action Plan for Seabird Conservation in New Zealand Part B: Non-Threatened Seabirds THREATENED SPECIES OCCASIONAL PUBLICATION NO. 17 by Graeme A. Taylor Published by Biodiversity Recovery Unit Department of Conservation PO Box 10-420 Wellington New Zealand Illustrations Front cover: Northern diving petrel, North Brothers Island, 1998 Inside front cover: Brown skua, Campbell Island, 1986 Source of illustrations All photographs were taken by the author unless stated otherwise. © May 2000, Department of Conservation ISSN 1170-3709 ISBN 0-478-21925-3 Cataloguing in Publication Taylor, Graeme A. Action plan for seabird conservation in New Zealand. Part B, Non-threatened seabirds / by Graeme A. Taylor. Wellington, N.Z. : Dept. of Conservation, Biodiversity Recovery Unit, 2000. 1. v. ; 30 cm. (Threatened Species occasional publication, 1170-3709 ; 17.) Cataloguing-in-Publication data. - Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0478219253 1. Sea birds— New Zealand. 2. Rare birds—New Zealand. I. New Zealand. Biodiversity Recovery Unit. II. Title. Series: Threatened species occasional publication ; 17. 236 CONTENTS PART A: THREATENED SEABIRDS Abbreviations used in Parts A and B 7 Abstract 9 1 Purpose 11 2 Scope and limitations 12 3 Sources of information 12 4 General introduction to seabirds 13 4.1 Characteristics of seabirds 14 4.2 Ecology of seabirds 14 4.3 Life history traits of seabirds 15 5 New Zealand seabirds -

Brookfield CP Bird List

Bird list for BROOKFIELD CONSERVATION PARK -34.34837 °N 139.50173 °E 34°20’54” S 139°30’06” E 54 362200 6198200 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Rainbow Bee-eater Mulga Parrot Eastern Bluebonnet Red-rumped Parrot Australian Boobook *Feral Pigeon Common Bronzewing Crested Pigeon Australian Bustard Spur-winged Plover Little Buttonquail (Masked Lapwing) Painted Buttonquail Stubble Quail Cockatiel Mallee Ringneck Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Australian Ringneck) Little Corella Yellow Rosella Black-eared Cuckoo (Crimson Rosella) Fan-tailed Cuckoo Collared Sparrowhawk Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Grey Teal Pallid Cuckoo Shining Bronze Cuckoo Peaceful Dove Maned Duck Pacific Black Duck Little Eagle Wedge-tailed Eagle Emu Brown Falcon Peregrine Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Galah Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe Spotted Harrier White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Nankeen Kestrel Red-backed Kingfisher Black Kite Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite Laughing Kookaburra Banded Lapwing Musk Lorikeet Purple-crowned Lorikeet Malleefowl Spotted Nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Blue-winged Parrot Elegant Parrot If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. SEASONS – Spring: September, October, November; Summer: December, January, February; Autumn: March, April May; Winter: June, July, August IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ONLY BIRDS SEEN WITHIN THE RESERVE ARE RECORDED ON THIS LIST. -

Download the Bird List

Bird list for PAIWALLA WETLANDS -35.03468 °N 139.37202 °E 35°02’05” S 139°22’19” E 54 351500 6121900 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Red-necked Avocet Black Falcon Spur-winged Plover (Masked Lapwing) Rainbow Bee-eater Brown Falcon Australasian Bittern Peregrine Falcon Australian Pratincole Black-backed Bittern Galah Brown Quail Eastern Bluebonnet Black-tailed Godwit Stubble Quail Australian Boobook Cape Barren Goose Buff-banded Rail Brush Bronzewing Brown Goshawk Lewin's Rail Common Bronzewing Australasian Grebe Mallee Ringneck (Australian Ringneck) Budgerigar Great Crested Grebe Cockatiel Hoary-headed Grebe Adelaide Rosella (Crimson Rosella) Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Common Greenshank Eurasian Coot Silver Gull Common Sandpiper Little Corella Hardhead Curlew Sandpiper Great Cormorant Spotted Harrier Marsh Sandpiper Little Black Cormorant Swamp Harrier Pectoral Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Nankeen Night Heron Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Pied Cormorant White-faced Heron Wood Sandpiper Australian Crake White-necked -

A Revision of the Australian Owls (Strigidae and Tytonidae)

A REVISION OF THE AUSTRALIAN OWLS (STRIGIDAE AND TYTONIDAE) by G. F. MEES Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden1) INTRODUCTION When in December 1960 the R.A.O.U. Checklist Committee was re- organised and the various tasks in hand were divided over its members, the owls were assigned to the author. While it was first thought that only the Boobook Owl, the systematics of which have been notoriously confused, would need thorough revision and that as regards the other species existing lists, for example Peters (1940), could be followed, it became soon apparent that it was impossible to make a satisfactory list without revision of all species. In this paper the four Australian species of Strigidae are fully revised, over their whole ranges, and the same has been done for Tyto tenebricosa. Of the other three Australian Tytonidae, however, only the Australian races have been considered: these species have a wide distribution (one of them virtually world-wide) and it was not expected that the very considerable amount of extra work needed to include extralimital races would be justified by results. Considerable attention has been paid to geographical distribution, and it appears that some species are much more restricted in distribution than has generally been assumed. A map of the distribution of each species is given; these maps are mainly based on material personally examined, and only when they extended the range as otherwise defined, have I made use of reliable field observations and material published but not seen by me. From the section on material examined it will be easy to trace the localities; where other information has been used, the reference follows the locality. -

Volume 28 Number 1 August 2010

BOOBOOK JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN RAPTOR ASSOCIATION Volume 28 Number 1 August 2010 ARA CONTACTS President: Victor Hurley 0427 238 898 [email protected] Acting Secretary David Whelan 0412 234 387 [email protected] Treasurer VACANT Webmaster VACANT Editor, Boobook Dr Stephen Debus 02 6772 1710 (ah) [email protected] Boobook production Hugo Phillipps Area Representatives: ACT Mr Jerry Olsen [email protected] NSW Dr Rod Kavanagh [email protected] NT Mr Ray Chatto [email protected] Qld Mr Stacey McLean [email protected] SA Mr Ian Falkenberg [email protected] WA Mr Jonny Schoenjahn [email protected] Tas Mr Nick Mooney [email protected] Vic (acting) Mr David Whelan [email protected] New Zealand VACANT PNG/Indonesia Dr David Bishop [email protected] Other BOPWatch liaison Victor Hurley [email protected] Editor, Circus Victor Hurley Captive raptor advisor Michelle Manhal 0418 387 424 [email protected] Education advisor Greg Czechura 07 3840 7642 (bh) [email protected] Raptor management Nick Mooney 0427 826 922 [email protected] advisor Membership enquiries Membership Officer, Birds Australia, Suite 2-05, 60 Leicester Street, Carlton, Vic. 3053 Ph. 1300 730 075, [email protected] Annual subscription $A30 single membership, $A35 family and $A45 for institutions, due on 1 January. Bankcard and MasterCard can be debited by prior arrangement. Website: www.ausraptor.org.au The aims of the Association are the study, conservation and management of diurnal and nocturnal raptors of the Australasian Faunal Region. -

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu O Aotearoa No.24 December 2019

BIRDS NEW ZEALAND Te Kahui Matai Manu o Aotearoa No.24 December 2019 The Magazine of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand NO.24 DECEMBER 2019 Proud sponsors of Birds New Zealand From the President's Desk Find us in your local 3 New World or PAKn’ Save 4 NZ Bird Conference & AGM 2020 5 First Summer of NZ Bird Atlas 6 Birds New Zealand Research Fund 2019 8 Solomon Islands – Monarchs & Megapodes 12 The Inspiration of Birds – Mike Ashbee 15 Aka Aka swampbird Youth Camp 16 Regional Roundup PUBLISHERS Published on behalf of the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand 19 Bird News (Inc), P.O. Box 834, Nelson 7040, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] Website: www.birdsnz.org.nz Editor: Michael Szabo, 6/238 The Esplanade, Island Bay, Wellington 6023. Email: [email protected] Tel: (04) 383 5784 COVER IMAGE ISSN 2357-1586 (Print) ISSN 2357-1594 (Online) Morepork or Ruru. Photo by Mike Ashbee. We welcome advertising enquiries. Free classified ads for members are at the https://www.mikeashbeephotography.com/ editor’s discretion. Articles or illustrations related to birds in New Zealand and the South Pacific region are welcome in electronic form, such as news about birds, members’ activities, birding sites, identification, letters, reviews, or photographs. Letter to the Editor – Conservation Copy deadlines are 10th Feb, May, Aug and 1st Nov. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily represent those of OSNZ (Inc) or the editor. Birds New Zealand has a proud history of research, but times are changing and most New Zealand bird species are declining in numbers. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations.